|

The black township of Kogiso is about 40 kilometres northwest of Johannesburg. The flat landscape is interrupted by old gold mining heaps which blanket the town with choking dust when the wind is from the south. As arsenic and mercury were probably used to extract the gold, the dust may contain a toxic legacy from mining companies who are long gone.

I arrive in Kogiso on a Sunday morning as women and children dressed in white, along with a scatter of men, walk to church. There are few cars in Kogiso, and the streets are turned over to people gossiping, and kids haring around playing ball games. This tranquil scene belies the reputation the black townships have for violence.

Kogiso is the home of Mama, as I am told to call her. I meet her in the front room of the community house, named in honour of her daughter Emily, who died in 2001.

Before she died, Emily (Jordan) Khwili Mabote converted a three-bedroom house to establish the Emily Jordan AIDS Centre with the help of donations from overseas. She was the first person in the township to publicly announce she was HIV-positive, and even today such honesty is not well received.

The struggle of AIDS-sufferers to elicit sympathy and support from their community is not helped by a government which underplays the extent of the epidemic. President Thabo Mbeki has been quoted as denying the link between HIV infection and AIDS, although more recently he has started to back-pedal.

South Africa has the sixth highest prevalence of HIV in the world, with 18.8% of the population estimated to be infected. The UNAIDS 2006 Global Report estimated that 320 000 people died AIDS related deaths in South Africa during 2005 with a further 5.5 million people living with the disease. AIDS affects every age group, and perhaps the most tragic statistic is that about 83 500 babies became infected with HIV through mother-to-child transmission. If current trends are not arrested, it is estimated that about one million South Africans will die of AIDS-related diseases by 2017.

Unfortunately the political signals have reinforced an unsympathetic view in the townships towards people with HIV-AIDS, which means they get little public support from the community or the church.

In 1990 Emily was diagnosed as HIV-positive after a still-birth. Over the next few years her health fluctuated, punctuated with bouts of TB, until she finally died. But she left behind a legacy to her community: a house where AIDS sufferers can go for moral and religious support, care and comfort. The Emily Jordan House opened six weeks before Emily died.

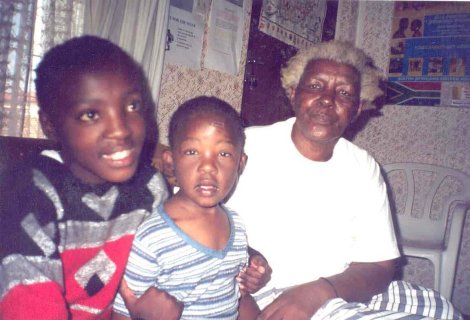

[Above] Evelyn, Lucky and Mama in the front room of the Emily Jordan House by photographer, year.

Christianity is evident everywhere in the House, from biblical quotes stuck on the fridge, to a clock with a picture of a radiant Jesus at its centre. A dispenser of condoms sits on the mantelpiece below the clock. Mama says that prayers are important in the struggle against AIDS. "We must wake up God," she says. Mama and other workers at the House also provide practical comfort by feeding residents and massaging aching limbs.

Not everyone in the township is as compassionate as Mama, or as willing to translate their faith into action.

A volunteer at the centre, Johanna Mogale, said it was very sad to see how people living with HIV/AIDS are treated by their own community.

"In many cases people do not even want to touch them, especially when they have wounds, and do not want to share utensils with them for fear of contracting the disease", said Mogale. "These people need love and support. In most cases relatives do not want anything to do with them and hide them when their condition deteriorates. [It is shocking] to find a sick person living alone in a cold shack in the backyard, not [being] looked after".

Families are ashamed of having HIV/AIDS in their midst, and sufferers often only obtain appropriate care when they are retrieved by Mama and taken to the Emily Jordan House. When families do bring their members to the House, it is usually because their family member's health has deteriorated to a point where they cannot manage by themselves. This feeling of disgrace is not helped by church leaders who say nothing from the pulpit about the disease. Some members of the congregation, thankfully, are active in providing comfort to AIDS victims but it is not something that they do openly.

Mama and I are joined by the manager of Emily Jordan House, Daniel Ncedani Mvala, who has arrived back from Johannesburg with provisions. He supplements the diet of those cared for at the House with fresh vegetables that he grows himself. He insists on showing me his vegetable garden, located on a wasteland on the edge of town. The soil is a rich brown colour, and cabbages, potatoes, beets and spinach are being grown. They are watered from a mean trickle of a stream 100 metres away. This prompted me to recall the trip into Kagiso. About ten kilometres before the township, well beyond the shadow of the tailing heaps, I passed the middle class town of Krugersdorp. On its edge are lush golf greens, where affluent members chip their balls around ornamental lakes. Such contrasts are all too common in South Africa, where political apartheid is dead, but economic apartheid is all too real.

When AIDS strikes, it is often transmitted from husband to wife, or vice versa, which has resulted in as estimated 1,200,000 orphans. Some orphans are left to fend for themselves, while others are more fortunate. As Mama makes me a cup of tea she explains that some orphans are taken in by relatives, usually the grandparents, while others are looked after by friends and neighbours. Mama tells me that she cares for Emily's three children, which, I thought, at 66 years of age, must test her strength.

As we are finishing our tea two rowdy children come into the room. They become shy when they see a stranger. Mama introduces me to Evelyn, who is aged about ten, and Lucky, a boy of about six. As well as her own grandchildren Mama adopted these two when their mother, Anna, died of AIDS within six month of Emily. In these circumstances, the nickname 'Lucky' seems inappropriate. Mama explains that Lucky was given his name because he was born disease-free after his mother had become HIV positive. |