THE HUMANIST POETRY OF FRANCIS WEBB

By Richard Hillman

Tree and Spinifex Grass, South Australia, Australia (Photo by Coral Hull, 2002)

A friend recently asked me to think about Francis Webb's poetry as a web. But, I ask, what is caught in such a web as language? 'The Runner', a poem that has only recently come to my attention, suggests that the web of his words is designed to catch a 'little spider of torment', a human kind of pain one might be running from, or towards. It is no coincidence that Webb's favourite sport was long distance running. But, for Webb, it is the pain of experience which emphasises human movement, this toing and froing (between love and hate) that articulates our humanity:

Brushed by the terrible hammer of the track,

The little spider of torment kicks and swings

In the grey, collapsing bubble of his lungs.

You will not see so pure a thing as this:

Movement alone, with its own emphasis.[1]

Each line, each tentative movement of the poem, bears witness to its own pain, or memory of pain. The silk thread of his metaphors are like motion sensors setting off alarms, needs and demands. Trying to keep up, the reader all too quickly becomes the runner - the senses speed up until you resemble Spiderman swinging from line to line, poem to poem, looking for a crime to solve.

|

No one is innocent; as this metaphor for human innocence in Webb's 'Foreword' suggests:

On their tindery pastures or wet

Those grazing cattle are not

True cattle, then, unaware.[2]

Webb discovers innocence in nature itself. For instance, in 'Nuriootpa', the countryside is 'innocent of offence', though language ('Good English') is complicit in the corruption of that innocence. In other poems, such as 'Laid Off 1. The Bureau, and Later', Webb is far more candid about the lack of humanity our social system has to offer:

I pitied the man behind the counter, who'd

Hear us be cruelly serious, hear us swear,

Be funny, No-speak-English - see us bowed

Under the weight of tools to make him God.

And in 'Galston 1. Bush Fire', Webb's realism clearly demonstrates the need to wake from the dream of a new nation in order to see the approaching fire of racism: |

[Above] Francis Webb (Photo by Claudia Snell, 1973)

For what moves on the horizon, hoodwinks the blinded sky,

Is one far threat gathering flame. Remote now, lovely,

That spring-toothed vision bearing towards the dream:

Only a blade of hatred, working and swaying,

Bursts through the lying saffron and shows itself.

Webb confronts love and hate to escape the inevitable confinement produced by a Romantic monocentric conception of humanity. His poetry tends to shift around the cultural margins, using analogy to describe the hypocrisy of poverty and wealth, life and death, in a post nuclear age. His social conscience stems from a close involvement with Christian humanism[3] but his discovery of hate as a vital component of humanity, sets his writing apart from a critical mainstream devoted to an exploration of love. For example, in 'The Father' (from Webb's well-known 'The Canticle'), written shortly after viewing August Strindberg's play 'The Father', he states:

I say, as a man: what was of me

Is offal. Can a last obstinate

Thread get past the double eye

And tinsmith's beauty of my hate?

In an effort to confront censorship, Webb's poetry leans in directions of thought that are not always popular, often displacing mainstream kinds of social inquiry. Analyses of his poetry are often defined or overshadowed by a restrictive discourse of love and grace within the context of his Catholicism when, in fact, the irony of his love-hate relationship with society deserves attention. Yet, this excerpt from 'Along The Peninsula' (written sometime between late 1950 and early 1951) suggests that Webb is interested in all the emotional possibilities of human experience:

The eye, really, holds still; it is always the mere

Skin and bone, flag and famine, love and hate walking

And passing, step by step:

Here is history, and we pass.[4]

In Australia, the biases of the Cold War allowed poets such as Vincent Buckley to view the rise of nationalism 'as a theatre in which we might discover God incarnate as love, as freedom and as strength'. [5] But 'Buckley's incarnational poetics ends the Incarnation' because it cannot escape the logos of the text itself.[6]

|

It is this bias towards a 'love system' [a legacy of Buckley's Christian humanism] which is problematised in Webb's work because the more he exposes the hate the greater the force to project the fantasy of love, or to at least indicate the existence of some 'good' in opposition to the persistence of a colonial 'bad'. This is similar perhaps to Judith Wright's desire for unity which cannot be met in a post nuclear age; there is a failure of the good that cannot be resolved in the writing process itself. In the poem 'Clouds', for instance, Webb is flying back into Australia following a seven year stint as a guest of English mental hospitals, and the predisposition to seeing the metaphoric linkage between himself and Australia in terms of 'love' masks the poem's more startling revelations about the colonial 'hate' to which he could be returning:

Plumb in the centre of all

Itinerant hatreds, loves,

Is this mentor, but all alone.

The poem strips away negative visions of a colonial identity his absence has held in suspension, like a cloud. His movement through these metaphoric clouds (entertaining visions of the 'Inland' and of 'The Town') and his descent into Sydney ('Airliner'), bring this conflict between love and hate into perspective, creating a space in which his arrival makes way for a post-colonial new - 'And now the elder sea all wrinkled with love/ Sways tipsily up to us'. |

[Above] Edward John Eyre (Cover Artwork by David Boyd, year unknown)

From this altitude, the poet, like Saint Augustine, is the jolly observer of the post-colonial child firmly attached to the nipple of the Australian landscape, or 'love aloft in those hands'.[7] His enjoyment (jouissance) is substituted by sardonic mirth, or jealous ire (jealouissance):"... a desire evoked on the basis of a metonymy that is inscribed on the basis of a presumed demand, addressed to the Other, that is on the basis of the ... Freudian Thing, in other words, the very neighbour (prochain) Freud refuses to love beyond certain limits."[8]

In 'Clouds', this 'neighbour' is Webb's vision of a colonial tainted subject he recognised in earlier poems ('Towards The Land of the Composer' and 'The Song of a New Australian'), a relationship he refuses lest he should 'drunkenly sing/ Of wattles, wars, childhoods, being at last home'.[9] Webb uses 'Clouds' as he uses 'fog', to contain and isolate a universal space in which new meaning is created - this reflects Webb's broader humanism, and his reliance on a vision of himself as other, re-negotiating the idea of the neighbour as the colonial oppressor. This idea of a love/hate relationship with one's neighbour, which also negotiates Webb's refusal of race-based violence, can be summed up in his [qua Eyre's] famous question (from 'Eyre All Alone') upon discovering that war has broken out between France and England - 'Lord, who is my neighbour/ On the long road to the Sound?'.

|

Such antagonisms always prove the human limitations imposed on Webb's idea of truth, but reveal the deep motivation behind his search for cultural companionship.

In an attempt to think about the antagonisms which exist between people, Webb explored this theme of love and hate, responding to the writings of both Saint Thomas Aquinas and Saint Augustine.[10] Of course, if one can hate, then one can love - and if love of Christ is affirmed by the notion that he loves us, it is because he does not hate us in turn. [11]

The misfortune of Christ is explained to us by the idea of saving men. "I find, rather, that the idea was to save God by giving a little presence and actuality back to that hatred of God regarding which we are, and for good reason, rather indecisive ... Thus, it may momentarily be convenient to make the Other responsible for this ..."[12]

Lacan argues that such a thing as racism, anti-Semitism especially, is the result of this search for a 'responsible' third party. And Webb himself struggled to free himself from an anti-Semitic culture (spurred on by artists such as Norman Lindsay) which blamed the other for its economic and sexual woes.[14] For Webb, this cycle of blame was something which could only be explained (often cynically) in terms of 'hate'. |

[Above] A Young Francis Webb (Photo by Claudia Snell, 1943)

"As for the Jewish man - no, hatred of him began in a nominally Christian world where common folk couldn't accept the dogma that Christ is slain by us all. And centuries of hatred and misunderstanding, wildly contrary to Christ's teachings, have of course resulted in some defence mechanisms within the personality here and there, perhaps even a temporary decadence - though such a generalisation will always have me on my guard."[15]

It would seem that a question of Webb's complicity - responsibility - is being asked. That he also views antagonism between social agents in terms of a defensive (negative) 'personality', should not be understated. On speaking of identity and the role of the poet, Webb states:

"Always - perhaps no more in our times than in others - the pressure of conformities threatens him and his way of breathing. That is why he tends to shape for himself a personality in which to live and write. Such a self-conscious formation of personality may be dangerous: it may result in a mere mask, or, run to seed, it may distort the rational and emotional integrity of experience and thinking ... Pitfalls await him: the facile, the repetitive, the pastiche."[16]

Webb almost always offers a balanced view of humanity. Perhaps this act of balancing personalities of love and hate, like Nietszche's tightrope walker or Marvel's Spiderman, keeps the poet aloft.[17] Webb is first to admit that 'St. Thomas Aquinas and Nietzsche are fundamentally more akin than are, say, Milton and Walter Pater'.[18] His poetry resembles the kind of stabilising activity a person performs in order to resist those moments of instability which so often punctuate a life.

At the heart of Webb's postwar poetry is a Dantean vision of the Holocaust, out of which evolves a dramatic conflict between responsibility and innocence, between the human and the divine, an argument that is tangled with personal and theosophic motives, but also one which injects some life into the politics of an apathetic present.

|

In a world where 'achievement', 'success', 'progress', 'sport' and 'love' are defining motifs of the human spirit, Webb interrogates the displacement of human responsibility these motifs actually articulate, though he does this without moralising. As suggested earlier, his poetry recalls James Baldwin's idea that 'it is innocence which constitutes the crime'.[19] In response to the crimes of humanity (such as the Holocaust, racism, sexual discrimination), he does not offer redemption nor seek atonement. Salvation, for Webb, is not mired as some Romanticised happy ending. His realism cannot afford the consequences. His poetry refuses 'mysticism' but embraces a deep connection between humanity and the environment. |

[Above] Corrugated Iron Roof, Rylstone, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

Webb's poetry articulates a renaissant humanism, a postwar poetry that engages the Enlightenment and the death of the modern subject with an aesthetic realism, a poetry that is constantly moving toward an awakening among his readers of 'a sense of human dignity'.[20]

The development of Webb's humanism has been confined by the misunderstandings of some dominant critics. These critics have concentrated on the density and obscurity of Webb's poetry,[21] his family history, his schizophrenia, and his religious idealism. Noel Rowe has recently argued that critics have placed too great an emphasis on biography when interpreting Webb's poetry. Martin Duwell has also argued that this kind of focus on family history fails to engage Webb's writing process.[22] I prefer Webb's own words on how to read his poetry: 'I write as my conscience, and my sense and senses and my critical views (even these part personal) direct me'.[23]

Webb honours a relationship between 'sense' and 'senses' that finds a companion in Nabokov's use of the words 'sentimental' and 'sensitive'.[24] Whereas Nabokov harbours ill-will towards the sentimentalist, he favours writing that is sensitive, ie. a writing process that makes use of both 'sense' and 'senses'. Webb could easily be mistaken for a sentimentalist, someone involved in an overly dramatic kind of writing which leans towards nostalgia, though to make this assumption about his poetry would amount to literary negligence. Often we find Webb exploring the terrain of historical repetition. For instance, in 'Disaster Bay', Webb evokes a song cycle of ships returning to the site of previous wrecks off the east coast of Australia. Here, the ghost of past salutes the ghost of present, a human comedy as each ship is found heading towards the repetition of disaster. Webb doesn't salvage his stories with happy endings. Instead, his poems appear like warning signs, 'red lights on the rocks' of a vast human struggle for composure. The poetry does make 'sense', contrary to the opinion of those superficial literary critics who haven't taken the time of day to consider Webb's semantics, or his humanist intentions, but have taken the time to lead criticism down the blistered throat of academic convention.

Webb's verse narratives often highlight those significant points where the past is about to meet the present, alerting his reader to a present that is open to possible interpretations and outcomes for the future. It would be impossible to provide anything but a glimpse into his poetry in a critique of this size, so I have prepared a response to one poem in particular, that is, to Webb's 'Towards The Land of the Composer'. In this poem, Webb explores what it is to anticipate something that might not, in the end, move in a humanist direction.

Towards the Land of the Composer

Rain tries the one small foot and at length the other

On the tin roof.

Valves of my cheap set

Manage your name after some notes on the weather.

And we must all be moving, with all our baggage:

Icon of knobby tree,

Kouros of long-tailed animal,

Lepidoptera,

River Yarra,

Harbour Bridge,

Four-letter words, and tons of more personal luggage.

|

And the best fire of 'em all, made of mallee roots,

Must stop this breezy nonsense,

Pull itself together

To run red and straight, after the swagman's boots.

And fair in the heel of the hunt our cloud-formations,

Our sun,

Our flocks,

Our tribespeople,

Grease of desert,

Blazing skewer of harvest,

The statues of Colonel Light, and the railway-stations.

And the heaven-bent squatters lash to their holy backs

Acre and acre,

Rifle and rifle,

The Family Tree,

The Family Bible,

At a sign from deadbeaters who carry only their packs.

And never a word nor a squeak from us when we meet

All the new islands,

All the old temples,

All the strange accents:

For the Leader has just this moment taken his seat.

And the latecoming bearded fish, and the smack and her

crew,

Man-eating headlands,

Crystal women,

Sagas of ice,

Front-seat fjords,

Whirling noiselessly in to be close to you. |

[Above] Salt Crystals at Lake Eyre, South Australia, Australia (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

The opening stanza is like 'a comment on poetry itself, the rain of an idea, the step of rhythm, the notion of tentative, the sense of an attempt, a trying out. A set of sounds that comes from outside the poem itself.'[25] Webb describes how rain begins to make a repetitive sound on his tin roof: 'Rain tries the one small foot and at length the other/ On the tin roof'. The corrugated iron roof conjures the world of the 'vernacular', something 'cheap', perhaps 'impolite', though there is an aesthetic reality in 'its receptivity to the fallen drop', the way the rain ripples down the spine of the poem like a foot upon someone's grave.[26] Each successive stanza produces a rippling phonic pattern of long and short steps/lines, the shorter lines being enclosed by the longer ones at the beginning and end of each stanza. Webb exists within the striding sound pattern of rain. These sounds come to him as footsteps. Unhurried. If these footsteps are moving towards the composer, then Webb has placed himself in a position to be approached. Something is laid out on the table here, exposed to our view, in a way that does not retreat from poetic scrutiny.

Webb, during moments of intense awareness, believed that his thoughts were picked up by radio and 'broadcast' (something that complicates our image of him as a radio operator during World War II); we are seeing Webb's grand opera, composed and conducted while this slow rain beats the time of an approach upon his roof. Yet, without a feeling of paranoia, these footsteps articulate the approach of someone moving towards the land of our composer. The metaphor for movement which envelopes the entire poem strongly suggests to whom these footsteps might belong.

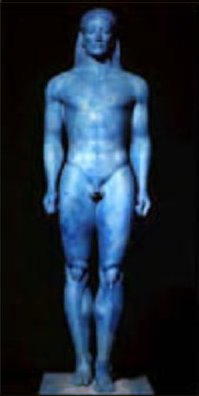

The second stanza reiterates the foot metaphor in its reference to movement - 'we must all be moving' - and through his visual metaphors for the feet:

And we must all be moving, with all our baggage:

Icon of knobby tree,

Kouros of long-tailed animal,

Lepidoptera,

River Yarra,

Harbour Bridge,

Four-letter words, and tons of more personal luggage.

The metaphor is exposed in the roots of the poem, literally, and in this sense the reader sees an image of the 'knobby tree' and its gnarled roots extending like feet, or the figure of the kouros, the Greek statue which bears resemblance to an ancient Egyptian god, a near-naked boy who steps one foot forward in a highly stylised stance, a tiny smile on his bland face.[27] The use of the kouros, for Webb, appears to be an act of counter-decadence, refuting the artistic decadence and anti-Semitism of Norman Lindsay. The figure of the kouros also holds several clues to interpreting Webb's poem. The kouros is that young god Geb who 'lies waning upon the earth, leaning upon a boulder and unable to rise until the appearance of a large bird carrying a chrysalis - the beginning and mystery of new life'.[28] According to Ruuskanen, the bird is long-tailed. If the chrysalis, the seed, is carried by the winged messenger, then Webb's wait is not a mystery - what becomes a mystery is the actual birth these images have prepared for us. In this sense, it is a birth which approaches through the colliding pattern of sound.

Webb does not speak of kouroi (the Greek plural). The plurality of rain itself implicates the reader in that process of oppression that is filling the country with expectation (or sense of dread) at the approach of this birth. An impending birth, summoning the possibility of danger, dogs the poem's footsteps. In the episodic movement, in 'the steady march of the impending', in the delicate pause between Webb's footfalls, comes the idea of a silencing, something which the rain is announcing in its repetition. This reference to 'the steady march of the impending refers already to this sudden silencing (or forgetting) that will inevitably occur'.[29] Elsewhere, Webb creates images of an impending presence that are oppressive. For example, 'River Yarra' on the map looks like a foot stepping into Port Phillip Bay (written about in 'Port Phillip Night'), and the 'Harbour Bridge' is not noted in this poem for its coat-hanger-like shoulders, but for its wide thighs, its thick colonial legs and feet extending downwards, straddling either side of Sydney Harbour. These statements make an abrupt point (followed up in Webb's 'The Song of a New Australian') about the experience of oppression in Australia during the 1950s. Yet, the counter-point to this argument is Webb's sliding of images together that anticipate some other outcome. For instance, in rhyming 'lepidoptera' with the 'River Yarra', is the poet making some kind of connection between this particular stream and butterflies, between Port Phillip Bay and birth?[30] In his poem 'Port Phillip Night' (from the same collection as the above poems), Webb refers to the arrival of the Bergen-Belsen, an ocean liner carrying survivors from the Holocaust, and the possibility of their substituting one concentration camp for another.[31] The point of such a poem is to suggest another outcome, something other than what already exists, something beyond the stereotypes of humanity that have already been put in place.

|

Stanza three extends the metaphor for the feet even further, linking the iconic 'mallee roots' to the stereotypic 'swagman's boots'. It is as if, beneath this falling rain, Webb is unveiling an iconic Australia, tentatively following in its laborious footsteps.

"Something is on its way, 'heaven throws down its spears', but it's just droplets after all, a release of grief, perhaps, for all unveiling marks the grief of what could not, until that moment, be uttered. And there is a grief in uttering for what is uttered now cannot be uttered again."[32] |

[Above] Sturt's Stony Desert, South Australia, Australia (Photo by Coral Hull, 2002)

In stanza four, Webb states that he is 'fair in the heels of the hunt'. Then, he refers to 'cloud formations', his metaphor for pregnancy, which shadow the countryside with the sense of an impending flood. He produces the wet season, raining down images that drench the continent out of its complacency, out of its vision of itself as empty:

And fair in the heel of the hunt our cloud formations,

Our sun,

Our flocks,

Our tribespeople,

Grease of desert,

Blazing skewer of harvest,

The statues of Colonel Light, and the railway stations.

To this, he adds another stanza filled with settlers and squatters, seeing them in the act of erecting 'signs', images of permanence in defiance of a nomadic life in Australia. It would appear as if the music of 'God's country' (to which Australia was often creatively referred and/or narrated) had yet to be 'heard', that 'all our baggage' had to be brought to it before anyone could 'take a seat'. This 'personal' baggage is imagined (by Webb) as a series of defiantly erected icons, the parts of a symbolic discourse yet to be spoken, the fine tuning of the orchestra prior to the opera, or the shuffle of feet and muffle of voices outside the doors of Woolworths prior to the grand opening. Yet, Webb is not content: in stanza six, he is questioning a social kind of silence, a form of oppression which has failed to question the politics of cultural baggage that is drowning this new-old stage:

And never a word nor a squeak from us when we meet

All the new islands,

All the old temples,

All the strange accents:

For the Leader has just this moment taken his seat.

Webb was particular about his capitalisation of significant words, and, in this instance, 'his' is not capitalised because he is talking about a new political entity, a 'Leader', not God, as if he is announcing that this someone is about to speak for these others (because they do not speak).

|

There is a feeling that Webb is filling a theatre with people, and in stanza seven he refers to the 'late-comers' and to his readership in the same space.

Here, everything is about to begin, or is filled with an immense anticipation - the preliminary music is like a monumental glacier creeping over the vast heat of the Australian continent, seeking the skin of his anonymous postcolonial audience: 'you', the late-comer, or new arrival. This final stanza evokes images of Australia drowning, being consumed in its own image, though an 'imported' image, that is closing in on 'you':

And the latecoming bearded fish, and the smack and her crew,

Man-eating headlands,

Crystal women,

Sagas of ice,

Front-seat fjords,

Whirling noiselessly in to be close to you.

The 'you' is presented as if Webb were handing over responsibility for these images to another, the post-colonial audience he is always addressing from the theatre of his poetry. In this poem we can observe a cultural metamorphosis - but also his resistance to culture?

Within the repetitive pattern of rain, Webb takes the opportunity to think about, to consider, the composition and the possibility of a response to the increasing presence of 'newcomers' to the continent. |

[Above] Kouros (Kouros by photographer unknown, year unknown)

The 'bearded fish' is another extension of 'kouros', twisting the image of the Sphinx, the bearded goddess of Egyptian history and mythology, into something entirely different. The 'fish' as a symbol of the Catholic faith is given a beard and the status of an icon. These latecomers have become tiny idols in Webb's eyes, have become little statues of gods. And through this analogy Webb returns the poem to its initial premise, that Australia is being composed beneath a deluge of imported icons, images that have saturated the mind of the composer. Webb views this flooded landscape as a 'bridge' to the 'composer'. In this sense, the statue is a 'transitional object', a symbolic thing that allows the audience to move towards the land of the author (just imagine Webb standing on his roof waving a baton and 'whistling all the themes from Beethoven's Fifth Symphony',[33] something he was apt to do from time to time as a party trick). In a theosophic twist, these icons do not conform with Webb's view of a Christian Humanism, rather they amount to a form of idolatry. But, if Webb came down from the roof, the way Moses came down from Mount Sinai, would he break the Commandments of his own humanism over the heads of the cow worshippers?

Webb does not offer violence (his story is different to the Biblical one). Yet, his audience discovers itself looking up at the corrugated stage of a new (perhaps neo-colonial) Australia. It is not surprising then, that the sequel to 'Towards the Land of the Composer' is entitled 'The Song of a New Australian'. In this following poem, Webb views Sydney as a concentration camp surrounded by barbed wire: 'Bridge is a coil of wire/ Slung on top of some upturned filthy cases' (127). It is this 'song' that Webb has prepared for his reader (that the poem has given birth to). The 'song' is a dissertation on Australia that can only be heard in terms of a humanity which has been forced into an unfriendly silence, gagged by colonial hate, where 'Mateship' (that paternal metaphor for the goodwill of Australia's post-invasion forefathers) is a mockery of love that rains prejudice against the new arrivals in Darling Harbour. There is no music in this poem, and its attack upon (or attachment to) the paternal spectre is a representation of Webb's vision of music as a bearer of loss, of a failed humanity, of a denied humanism. In this final sense, Webb asks his readers to move beyond denial, to re-negotiate their humanity outside the space of the poem.

[Above] Barbed Wire and Star Picket Fence, Rylstone, New South Wales, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

Bibliography:

[1] Francis Webb 'The Runner' in Peter Meere and Leonie Meere Francis Webb: Poet and Brother: Some of his letters and poetry (Pamona, Qld: Sage Old Books 2001) 68.

[2] Francis Webb 'Foreword', ibid., vii-viii

[3] Michael Griffith God's Fool: The Life and Poetry of Francis Webb (Sydney: Angus & Robertson 1991): discusses Webb's involvement with Christian humanist groups during his time in Melbourne. Also, reference to Webb's Christian humanism can be found in Graeme Kinross Smith 'The Gull in a Green Storm - A Profile of Francis Webb (1925-1973)' in Westerly Vol.26, No.2, 1981, p.49.

[4] This extract contains the first four lines from Francis Webb's three part poem 'Along The Peninsula': first published in Meere and Meere, pp.27-29.

[5] John McLaren [1996] Writing in Hope and Fear: Literature as Politics in Postwar Australia, Oakleigh, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, p.29.

[6] Noel Rowe 'Giving A Word To The Sand' in Westerly Vol.45, 2000, p.155.

[7] Jacques Lacan [1999] The Seminar of Jacques Lacan: On Feminine Sexuality: The Limits of Love and Knowledge Book XX Encore 1972-1973 London: W.W. Norton & Co., pp.99-100. Quote taken from Webb's 'The Canticle', Cap & Bells, p.107.

[8] Ibid, Lacan, p.100.

[9] From London in 1953, Webb wrote to Douglas Stewart (then editor of The Bulletin) that he would 'never, while a single sense still serves me true during waking hours, return to Australia' (5/6/1953, NLA MS 4829): in Meere and Meere, p. 110.

[10] Lacan, pp.98-100: Lacan was also responding to Georges Bataille and Levinas.

[11] Ibid, p.98: Lacan rephrased.

[12] Ibid, p.98.

[13] Ibid, p.99.

[14] Andrew Lynch 'Remaking the Middle Ages in Australia: Francis Webb's 'The Canticle' (1953)' in Australian Literary Studies Vol.19, No.1, 1999, p.46.

[15] Francis Webb in Meere and Meere - quote is taken from a letter to the editor of Southerly Vol.21, No.1, 1961, p.48: the reference to 'decadence' may have been a jibe aimed at Norman Lindsay.

[16] Ibid, p.viii - quote taken from Francis Webb's review of Hugh McCrae's poetry in The Bulletin 30 December 1961, p.35.

[17] Friedrich Nietzsche [1978] Thus Spoke Zarathustra Ringwood, Vic: Penguin Books. Also, Freidrich Nietzsche [orig 1889; 1978] Twilight of the Idols and The Anti-Christ Ringwood, Vic: Penguin Books.

[18] Francis Webb (correspondence with Peter and Leonie Meere: 14/1/53) in Meere & Meere, p.81.

[19] James Baldwin The Fire Next Time Ringwood, Vic: Penguin, 1964, p. 14.

[20] Belinski's 'Letter to Gogol' in Vladimir Nabokov Lectures on Russian Literature London: Picador, 1981, p.97, rephrased.

[21] Noel Rowe 'Deviation and Devotion: Francis Webb's 'Homosexual' in Xavier Pons (ed.) Departures: How Australia Reinvents Itself Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2002, pp. 184-191.

[22] Martin Duwell 'Book Review: Michael Griffith's God's Fool, Australian Literary Studies Vol. 13, No. 4, 1992, pp. 362-364.

[23] Francis Webb quoted in Michael Griffith's God's Fool: The Life and Poetry of Francis Webb Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1991, pp. 96-97.

[24] Vladimir Nabokov Lectures on Russian Literature London: Picador, 1981, p. 103.

[25] John von Sturmer 'Towards the Land of the Composer: entering the web' in Springfield Gazette No.5, 2004, private circulation, p. 5.

[26] Ibid., p. 6.

[27] Webb mentions a volume of Greek Sculpture loaned to him by Leonie Meere, in correspondence dated 16/2/1952, from which this image may have been drawn: Meere and Meere, p. 47.

[28] Maren Kuether-Ulberg Epiphany and Renewal: The Goddess and Her Birds in Minoan Art, part 2, n.d.

[29] John von Sturmer, p. 6.

[30] Ibid., p. 7.

[31] 'Port Phillip Night' is a brilliant contemporary satire which uses Felix Mendelsohn's Fingal's Cave Overture (a violin concerto) to orchestrate the arrival of the Holocaust survivors in Australia.

[32] John von Sturmer, p. 6.

[33] Meere and Meere, p.75.

Richard Hillman gratefully acknowledges Dr. John von Sturmer's assistance with preparation of this response to Francis Webb's poetry.

About the Writer Richard Hillman

|

Richard Hillman grew up in the outer western suburbs of Sydney with his mother Liz, elder brother Brett and younger brothers Shane and Daniel. When Richard left school he worked in a variety of jobs whilst completing tertiary studies at CSU (Charles Sturt University). This included lecturing at the UWS (University of Western Sydney). He moved to Adelaide with wife Allison ("the concrete goddess who gathers no moss") and their three children Lachlan, Shanyn and Bronte, where he has continued his studies at Adelaide University, and Flinders University of South Australia. Richard has completed a PhD in Australian Studies, specialising in the writings of Jacques Lacan and the poetry of Frances Webb. Richard is currently Director of The SideWaLK Poets Collective Inc., and publishes books under the SideWaLK label. He is also a contributing editor for papertiger, an international CD-ROM poetry journal. Richard's career as a writer has included radio talkback shows, live internet performances, and readings at many of Australia's most well-known literary establishments. His poetry has been published widely throughout Australia, New Zealand, Europe and the USA. His most recent collection of poetry is Jabiluka Honey (Bookends Press, 2003). |

[Above] Photo of Richard Hillman and Co. by Duncan Kentish, 2002.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.9 (March, 2004) |