A 'BUNYAH BUDDHA REALM'?:

A BIOREGIONAL APPROACH TO LES MURRAY'S HEARTLAND

By Paul Cliff

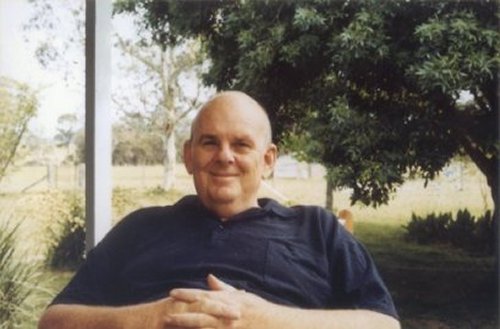

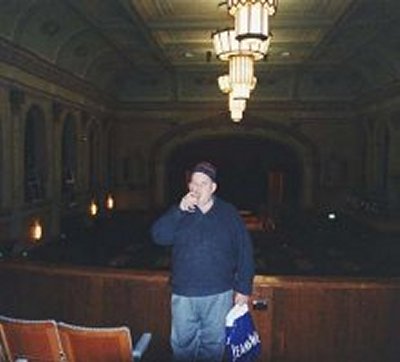

[Above] Portrait of Les Murray 1 (Photo by Valerie Murray, 1997)

The following is excerpted and adapted from a book manuscript in preparation entitled 'The Angel In It': Les Murray at Bunyah; A Critical Cartography. [1] The work is built on a taxonomy of all the 'Bunyah' poems as confirmed by the poet, accompanied by detailed readings of the poems, and supported by interviews and correspondence with the poet and visits to his property and surrounding region. The present extract considers parallels between Murray's presentation of his native region and the approach of bioregionalist theory, making some reference to the American environmentalist and poet Gary Snyder, and touching on Bunyah's flora and fauna, and its Aboriginal representation.

Bioregionalist theory and practice

Les Murray's assiduous, large-scale and protracted documenting of his native region of Bunyah, on the mid north coast of New South Wales - over a 35-year period, and with its very specific focus on 'place', its faithful absorption of 'real world' geophysical, historical and seasonal detail, and portrayal of Bunyah as a distinctive, living and integrated community - has broad sympathies with a bioregionalist approach to reading landscape.

Bioregional philosophy, gaining impetus through the environmental movement in 1970s and 1980s North America, makes an organic reading of 'place' as a distinctive, unified ecosystem defined by geophysical indicators (local watersheds, flora and fauna, geology and weather patterns) and cultural ones (history of local human habitation, evolution as a community, presence and arrangement of material constructions and socio-economic structures). A bioregional approach not only understands, but also values, the interconnected and sustainable (symbiotic) workings of these individual components. It also addresses the issue of 'outside' or exotic elements which are introduced into (and absorbed by) the community to become part of it. One prominent advocate has expressed bioregional concerns as follows [2]:

[Above] Brown pin-oak leaves and upper dam, with frost beyond, Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Valerie Murray, 2002)

Ecosystems are connected by geologic systems and water systems, and linked by other processes such as wind currents and bird and animal migrations ... The picture grows even more complicated when you add to it the many kinds of systems that human beings create - business, international organisations, informal networks of all kinds ... If you want to become grounded in your environment, you need to get in touch with all its parts. This means knowing about the systems that are built by human beings [and] the plants and animals that are imported from other parts of the world.

[Above] The feedshed next door to the poet's current property, Bunyah, New South Wales Australia (Photo by Paul Cliff, 1997)

The bioregional perspective has political, economic and social dimensions which value: regional and communal scale; conservation, self - sufficiency and cooperation; decentralisation and complementarity; and symbiosis and organic evolution. A bioregional approach can be viewed under four headings: Scale (endorsing life at the level of region and community - as opposed to the 'Industrial Scientific' paradigm of state and nation/world); Economy (valuing conservation, stability, self-sufficiency, and cooperation - as opposed to exploitation, change/progress, the world economy and competition); Polity (favouring decentralisation, complementarity and diversity - as opposed to centralisation, hierarchy and uniformity); and Society (working via symbiosis, evolution, division - as opposed to polarisation, growth/violence and monoculture) 3.

Another, simpler definition of the bioregionalist approach comes from a current American web site 4. This defines bioregionalism as: a fancy name for living a rooted life. Sometimes called 'living in place', bioregionalism means you are aware of the ecology, economy and culture of the place where you live, and are committed to making choices that enhance them.

A bioregion is: an area that [exhibits] similar topography, plant and animal life, and human culture. Bioregions are often organised around watersheds, and they can be nested within each other.

The same website incorporates, under the heading 'Living Bioregionally', the following dot points: 'knowing the birds, animals, trees, plants and weather patterns of your place, as well as land features and soil types'; 'understanding the human cultures that have occupied your place in the past, and respecting their ways of life'; and 'getting to know your neighbours' and 'looking out for each other'.

|

Again the inherent political nexus is pointed up - bioregionalism being expressed broadly as an anti-global and (interestingly, given Murray's own recurrent and disparaging deployment of the same term) 'anti-fashion' movement, which is opposed to:

a dominant culture that seeks to draw as many people as possible into the urban high-consumption lifestyle and to wipe out differences between regions, replacing them with a monoculture of consumerism and Hollywood entertainment. In this type of culture, a locally-centred life is labelled parochial and old-fashioned. This image is one that the global economic forces continually reinforce, since locally based economics not only does not fit with the global vision, but is actually a threat to it.

Describing bioregionalism's positive impact on a given community's culture and 'civic life', the website proposes the following advantages: Grassroots democracy flourishes; civic life develops the vibrancy that comes when people feel that their opinions matter and when they care what happens to their community. Big money and special interests have much less power. |

[Above] Looking west up the house dam at Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Valerie Murray, 2001)

The result is that: Communities are cohesive, neighbourliness increases and people help each other more, with small and large problems. Local culture likewise flourishes, because: music, art, drama, storytelling, games ... arise from the local community and the people's sense of connection to their environment and each other.

It can be noted that the above-stated approaches, values and impacts of bioregional theory and practice might be seen to have broad complementarity with many of Les Murray's own 'Boeotian', 'Vernacular Republican' and other stances expressed across the full range of his poems, essays, newspaper columns and sundry letters-to-the-editor over a 35-year publishing career. [5] The same broad spirit of 'place' underlies (or is variously touched on in) the essays which Murray groups under the heading 'Vernacular Matters' in his collected prose (A Working Forest, pp 107-216). To briefly sample just four instances: in his declaration that the 'vernacular republic ... is the subsoil of our common life' ('The Australian Republic', AWF 110 at 112); his championing of the 'earthed' Boeotian poet Hesiod ('On Sitting Back And Thinking About Porter's Boeotia', AWF 121); his concept of 'Strine Shinto' and the quest for national and communal identity ('Some Religious Stuff I Know About Australia', AWF 130); and his discussion of the abortive New State Movement in the New England region of northern New South Wales (abutting his own native region) - in which he notes that region's distinctive topography and 'own atmosphere and traditions' ('Snow Gums', AWF 178 at 181). Beside these, more specifically as we will see in detail presently, bioregionally-empathic approaches underlie or inform his key Bunyah essays 'A Generation of Changes' (mid-1980s), 'In A Working Forest' (1990) and his text to the book of photographs The Australian Year: The Chronicle of our Seasons and Celebrations (1985).

[Above] Frosty paddock seen from west verandah, Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Valerie Murray, 2002)

Gary Snyder: bioregionalist and poet

In the above light, it is interesting to consider bioregionalism's understanding of the spirit of place by reference to another poet - and an avowed bioregionalist - the American Gary Snyder (b. 1930). Snyder's comments (following) would, one senses, find considerable endorsement from Murray - and likewise find some overlap with Murray's own self-defined 'Boeotian' stance on the world. Moreover, Snyder's focus on the importance of the 'formative childhood years' in this is also interesting, given Murray's own recurrent childhood-and-adolescent Bunyah evocations in his poems, and in his expressed motive ('Extract From A Verse Letter To Dennis Haskell', CP 275 at pp 275-6) to give his three youngest children a 'country childhood' as being a key impulse for the family's 1986 return from Sydney to Bunyah.

As Snyder puts it: most people throughout all of human time have come from a place and have grown up there or lived there most of their lives and [formed] a rich experience, a rich body of lore and knowledge about a place ... We are not only members of communities, but in turn communities are members of places, and it is a critical part of normal psychological and intellectual development to be in relationship to a place, especially in your formative years ... If you don't understand where you are, your place, you can make a lot of silly mistakes. Accuracy and clarity and affectionate understanding of place are our very first move. [6]

Snyder's words chime with the spirit of Murray's own Bunyah poems - and much of his other, broader work. They resonate with Murray's obsessive, imaginative farming of his 'spirit place' during the long years away (1957-1985), and with his repeated poetic attestings to Bunyah's capacity for providing physical and spiritual restoration.

|

(For his psychic 'integration' as he expresses it, for instance, in the 'Preface' of 'The Idyll Wheel', CP 285 at 285: 'Being back home ...

where I am all my ages'.) Similarly (as detailed in chapter 8) such a sense of 'place' furnishes the ideological crux of Murray's longest, single Bunyah-centred work, The Boys Who Stole the Funeral (1980).[7]

Murray might also endorse Snyder's following emphasis on place and community (an almost parallel expression of the ethos of Murray's own poem 'Fastness', CP 249): People are a part of place ... Place is the bioregion [which requires to be read] not only in a natural-history, ecological way, but in a spiritual way, reading it as 'these are the forces that shape the ground here, the community here'. Again, Snyder's commentary on the process of coming to grips with regional surrounds might also appeal to the Australian poet. Giving the example of his own transcontinental move to an 'unknown' California, Snyder recalls how he pro-actively sought intimacy with the new terrain by means of: going out and camping in it, walking in it, smelling it, addressing myself to it, quickly learning flowers and plants and birds, quickly learning to read what was going on ... to read California ... |

[Above] Cricket, Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Valerie Murray, 1994)

Exactly as Murray - in his persistent revisitings from Sydney and Canberra during the years of exile (1957-85), and then upon his permanent return in 1986 - walks, drives and 'reads' the Coolongolook River, Wang Wauk forest, and the surrounding hills, paddocks and roads of his own native 'Bunyah' - or more widely, Manning River valley. And exactly as the revisiting city folk re-establish temporary contact with that regional geography - moving through the north coast paddocks and waterways; standing under day and night skies - in 'The Bulahdelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle' (CP 137); or, again, in The Boys Who Stole the Funeral (see sonnet 60). As mentioned, these regional 'specifics' are addressed in another key Bunyah work, Murray's 'A Generation of Changes' essay (AWF 45 - see chapter 2) which sets out five tables cataloguing the decades of change he has observed in his native region. The essay lists items under the headings: 'increased or become prevalent' (eg, echidnas, elastic-sided boots); 'decreased or become less common' (eg stumps with board-slots); 'appeared during my absence' (eg brick houses on country holdings); 'vanished during my absence' (eg - perhaps surprisingly - bullock teams); and 'vanished before my time but still remembered' (eg river and coastal shipping). As shown in the detailed examination of the Bunyah poetry itself (Part B of present work), Murray's active and recurrent incorporation of many of these same images into the weave of his poems demonstrates to the highest degree his impulse to intimate 'bioregional' observation and identification.

It is notable that Murray also opens and closes his 'Generation of Changes' essay-catalogue with declarations strongly sympathetic to the bioregional ethos. He prefaces the catalogue with consideration of the local transport networks (describing the successive demise and ascendancy of river, rail and road transport); and ends it by speculating on a creative application of his 'list' approach by other regionalists elsewhere in Australia: Given the surge of interest in recent years in local and oral histories, my simple lists may suggest a framework for recollection in other regions. And maybe, taken singly or together, such listings might add up to a resource.

Gary Snyder, continuing his own analysis of 'place' and stressing the importance of the geophysical elements, expresses it in terms of the Eastern religion he himself spent many years practising:place is coterminous with such terms as ecosystem and watershed and natural community. Place is specific of a swirl of climatic annual forces, ranges of temperature, ranges of water fall ... the whole of a place constitutes what in the Buddhist sutras we might call a little Buddha-realm. [8]

In Murray's case, we might say a 'Bunyah Buddha-realm'? - or perhaps more aptly a 'Bunyah Presence' - aligning it to his own Catholic faith, and the concept of 'presence' as he deploys that word in the title of the major sequence in his ninth collection, Presence: Translations From The Natural World (CP 371-96).

|

It is further worth noting in passing, incidentally, that Murray's use of the word 'translations' in this same title picks up interestingly on Snyder's own metaphor of 'reading' place (in his just-quoted references to his Californian acclimatisation). Moreover, turning it around, Murray himself has elsewhere used Eastern religious terms to express Australia's own spirit of place - talking for instance (again as just noted) of 'Strine Shinto' in his essay 'Some Religious Stuff I Know About Australia' (AWF 130). And yet again - reciprocally - one would imagine that Murray's concept of abandoned Bunyah farmhouses becoming 'shrine houses' to the local community (as expressed in the poem 'Crankshaft', CP 401; and demonstrated in Kevin Forbutt's resumption of his great uncle Clarrie Dunn's dilapidated domicile at the end of The Boys Who Stole the Funeral) would equally appeal to Snyder. As Murray describes such houses in interview: ... they keep them clean, as if the old [residents] were going to come back, as if the spirit still lives in the house ... sometimes after the person dies, the house just rots away and falls down; at other times it gets sold and comes back to life. Just over the hill [from here], the first house you come to ... was a shrine house for 12 or 15 years ...[9] |

[Above] Patchwork Tile Chimney, Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Valerie Murray, 1990)

Finally, Gary Snyder raises his bioregional analysis to the 'political' level in a way which we might again suspect Murray would heartily endorse: So here's a thought ... We have not quite thought of place as a player on the political stage. Yet place is the ground of all political communities. Place is the mandala that embraces natural societies, and natural societies are in turn the mandalas that embrace artificial societies like states and governments.

In sum, it seems reasonable to say that at the least - and although Murray never specifically uses the term 'bioregion' itself - his Bunyah poetry, and a significant amount of his critical writing and essays, show substantial sympathy and considerable overlap with 'bioregional'-type concerns and emphases on 'place'. His assiduous mapping of the 'forty acres' and the wider range of his 'spirit country' in the Manning Valley - particularly from the collection Ethnic Radio (1977) onwards - reveals persistent and often 'scientific' or 'documentary'-style bioregional imperatives. This faithfulness to place is also continuously present as 'read' through the Bunyah poems' various personae: particularly the lifetime experience of Cecil Murray (as 'late pioneer', timberworker, dairy farmer and Bunyah denizen), and that of sundry other Murray forebears, family, clan and wider community members, as well as in Les Murray's own expressed first-hand experience of growing up and living at Bunyah.

A 'bioregionalist' sympathy is likewise suggested in Murray's particular attention to Bunyah's geophysical detail and associated seasonal weather patterns - as seen in his 1985 prose work The Australian Year: The Chronicle Of Our Seasons And Celebrations, and in his massive cyclic celebration ('farmer's almanac') 'The Idyll Wheel: Cycle of a Year at Bunyah, New South Wales, April 1986-April 1987' (CP 285) - as well as in such smaller individual poems as 'Two Rains' (CP 308). The geophysical interest is manifest in his recurring observation of the Bunyah watershed (in both naturalistic and more metaphorical terms) - local and regional rivers, creeks and lakes - and in his evocation of many regional species (both native and introduced). It is also implicit in his championing of the work of another rural 'bioregionalist', Eric Rolls (who celebrates the Pilliga area of New South Wales) 10 - and in Murray's own like-spirited essay, 'In A Working Forest' (AWF 57; discussed at end of present chapter) which celebrates the local Wang Wauk state forest in which Murray's father and forebears worked, and in which he himself roamed and continues to roam in childhood and adulthood. Both Rolls and Murray blend a physical depiction of the natural world with a focus on human penetration of their local regions - incorporating Aboriginal history, white pioneer history, and family and regional lore, in a manner highly sympathetic with a bioregional understanding of 'place'.

[Above] Pete with Chook House Construction, Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Valerie Murray, 1991)

Indigenous representation at Bunyah

This devotion to the spirit of place also underlies Murray's conception of his own family's 'Aboriginal' connection (both literal and metaphorical) 11 to Bunyah land - and his expressed indebtedness to Aboriginal culture. (Murray's interest in, and the extensive influence on him of, Aboriginal culture and religion is outlined in his 1977 essay, 'The Human-Hair Thread'.12). In his poetry, Aboriginal traditions feature symbolically in the 'common dish' vision towards the end of The Boys Who Stole the Funeral (sonnets 120-33) - in the figures of Birrigan and Nimbin and the quartz crystal 'initiation'. It also famously manifests (both in terms of technique, and sentiment) in his remodelling of traditional Aboriginal song cycles to cast his expansive hymn to his native region, 'The Bulahdelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle' (CP 137 - see separate discussion, chapter 7). True to its title and the spirit of its Aboriginal model, this poem 'sings' the regional landscape in a series of taut, lively, finely focussed cameos and longer 'cinematic' sequences. The work has a pronounced bioregional focus, a perhaps inevitable consequence of Murray's fairly faithful following of both the spirit and broad technique of the poem's model, R.M. Berndt's translation of the Wonguri-Mandjikai 'Song Cycle of The Moon Bone'. (Murray included the latter in his Oxford Book of Australian Verse, 1986 and subsequent.)

|

In the small space available here, however, it is useful to consider the issue of Bunyah's Indigenous content in a shorter poem (with a slightly longer title): 'Thinking About Aboriginal Land Rights, I Visit The Farm I Will Not Inherit'(CP 93). This is an intense piece, loosely embittered at its edges, whose epic title has several strands of significance for Murray's mythological framing of Bunyah, resonating as it does with an 'Aboriginal' 'tribal'-familial connection for the hereditary, 'native', Murray lands. |

[Above] Les Murray 2 (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2000)

Accentuated by its mythological conclusion - with the persona being absorbed into the landscape - it expressly frames Bunyah in 'Indigenous' terms, setting Murray's loss in the same frame as his rural 'fellow-relegated', the Aboriginals, and their own contemporary, topical (at the time he wrote the poem in the early 1970s, and now) struggle for traditional lands.

Poised between lyric and elegy, the piece opens in 'real world' seasonal Bunyah, with the persona 'watching from the barn, the seedlight and nearly-all-down/currents of spring day' and reading an order into the landscape: 'the only lines bearing/consistent strain are the straight ones: fence, house corner,/outermost furrows'. The speaker considers how easily the surrounding bush could reclaim the farmland, extinguishing the settlers' imprint as easily as it initially received it - the White incursion obliterated by the irrepressible vitality of nature. 13 This connects, via the 'Aboriginal' mythological device, to the projection of the persona himself as merging epically with 'his' own landscape: 'By sundown it is dense dark, all the tracks closing in./I go into the earth near the feed shed for thousands of years'.

As well as its Aboriginal mythological association, this image of 'going down into the ground' is contextualised by, and works via, its evocation of past generations of the Murray family literally interred in the Bunyah region. And the image of the 'feed shed' (in reality the dilapidated house where Cecil Murray was born, now just over the fenceline of the current Murray property) seems weighted with the conception of Murray himself (and the past generations) 'feeding' the land - as well as Murray's reciprocal imaginative feeding on, and sustenance from, the 'sacred Murray ground'. Against this general 'mythological' framework, and true to a 'bioregionalist'-type imperative, 'Bunyah' is also evoked here in terms of its 'real world' micro landform - the detail of the grass, dust, pollen and oils - the emollients - the natural activities of the land sustaining itself; then stretching to the idealised, Edenesque, image of the 'bee trees unrobbed'. The poem achieves power as a gentle, classically simple, naturally moving yet intense meditation - which, via the device of the title, is plainly assertive in its declared 'native' connection to this parcel of regional land.

[Above] The Poet's House, Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Paul Cliff, 1997.

Elsewhere, Bunyah's Aboriginal component is recurringly evoked at multiple levels, ranging from mention of the practice of burning the land, specifically touching on regional Aboriginal history (the Kattang people described in his essay 'A Working Forest'; a reference to an Aboriginal sharing his great great grandfather's pioneer plot at Kimbriki, in 'Earth Tremor At Night', SRP 66), and the residual language in local place names (eg, 'Coolongolook', meaning 'roughly Leftward Inland/from gulunggal, the left hand' - 'Aspects of Language and War on the Gloucester Road'; CP 279).

As an indicator of the broader intrinsic alignment of Bunyah to bioregionalist themes and approaches, Table A (following) places some individual Bunyah poems into the five specifically nominated categories ('windcurrents and water systems', 'human systems', 'flora', 'geologic systems', and 'bird and animal migrations') which bioregional theorists propose as key identifiers to 'place'. 14 Apart from the specific poems listed here, many other incidences of such alignment occur in individual lines embedded within other Bunyah poems - creating a 'Bunyah-bioregional matrix' or underlay to Murray's work.

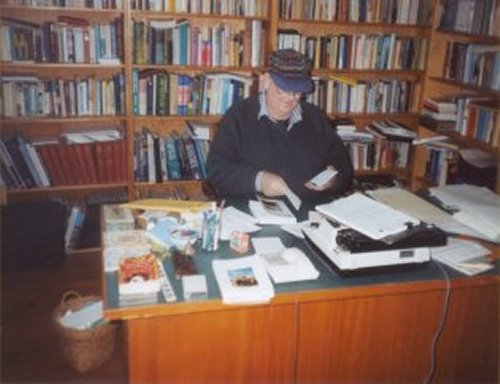

[Above] The Poet At Work, Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Paul Cliff, 1997)

TABLE A: SAMPLE BUNYAH POEMS ALIGNING TO FIVE KEY 'BIOREGIONAL' SIGNIFIERS

Wind currents and water systems (rains): Murray's interest in the ecology, history and spiritual dimension of rivers and creeks (and floods), estuaries, lakes, and dams at the 'forty acres' and surrounding region straddles a wide range of poems. For instance, his floating in the Coolongolook River in 'The Action' (CP 113); his rowing along it in 'The Returnees' (CP 125); his recalling the old mill at its bank, in 'Coolongolook Timber Mill' (CAV 25); his walking the river course evoked in 'The Gallery' (CP 130). Likewise there is: 'Dead Trees In The Dam', 'Water-Gardening In An Old Farm Dam' and 'Dry Water' (SRP 18, 45 and 183 respectively); and 'Like Wheeling Stacked Water' (SRP 31). More recently there is the folkloristic account of earlier dam-making and cleaning in 'The Water Plough' (CAV 40); and the rain-soaked paddocks of 'The Long Wet Season' (CAV 70).

At a further remove there is: 'At The Aquatic Carnival' (CP 236), and 'On Home Beaches' (SRP 36); 'Freshwater And Salt' in 'The Idyll Wheel' (CP 296); 'The Lake Surnames' (the Myall Lakes, CP 257) and 'Wallis Lake Estuary', 'Twin Towns History' (also located at Wallis Lake; SRP 33 and 34); 'To Me You'll Always Be Spat' (CAV 33); and 'The Derelict Milky Way' (CAV 60).

Wind and rains: 'Two Rains' (CP 308); also 'Cumulus' (CP 225), and 'The Warm Rain' (SRP 93). [With regard to water imagery, it is illuminating to visit the Murray property itself. A visit in mid-winter 1997 discovered the 'forty acres' engulfed by images of water: squelching underfoot in the quaggy paddocks, coursing through Horses Creek arcing along the back of the property, running off adjacent inclines, resounding in small cataracts, rising in the dam immediately behind the house, and beading in condensation on the domicile's window-panes. It seemed entirely inevitable that the Bunyah poetry (particularly as projected in the Subhuman Redneck Poems collection) abounds with such imagery.]

Human systems:

|

Murray's Bunyah evocations depict the networks of the local human community in manifold ways. Broadly, there is the conceptual position in the non-Bunyah poem 'Fastness' (CP 249) where Murray talks about the need to know the 'hill air' and the 'taste of local tank water' in order to truly understand (and thus evoke) a particular local people and their communal lore. |

[Above] [Above] Firewood in car shed at Bunyah, Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Valerie Murray, 2001)

Or, again, his declaration of the need to know 'the names, and the words those people used to name things', at the end of his essay 'In A Working Forest' (AWF 57 at 72-73).

More specifically, and in Bunyanesque terms, the understanding of 'human systems' is in Murray's examination of his own community -

initially through his father Cecil's experience as bullocky, timbergetter and farmer, connecting back through family history and lore via the Murray lineage as pioneer district settlers. In addition to the 'In A Working Forest' essay, the timbergetting community is evoked in the poems 'Driving Through Sawmill Towns' (CP 10), 'The Edge Of The Forest' (CP 115) and 'To The Soviet Americans' (CP 309); and, more tangentially, 'Coolongolook Timber Mill' (CAV 25). The regional dairying community is evoked in 'The Milk Lorry' and 'The Butter Factory' (CP 253 and 254 respectively).

The human networks are also expressed through the more recent (and current) family iconography (aunts, uncles and cousins) underpinning Murray's work - and other 'feral' lore set in the region. And particularly in the two extended socio-historical meditations, 'Aspects Of Language And War On The Gloucester Road' (CP 279) and 'Crankshaft' (CP 401), incorporating local lore and history - right down to the detail of the council's replacement of old wooden bridges with new concrete ones.

|

Representation of Bunyah's human systems also incorporates consideration of newcomers and passers-through (again, 'Aspects Of Language And War On The Gloucester Road' and 'Crankshaft'). It documents the old pioneering families who settled around Myall Lakes ('The Lake Surnames', CP 257) or the Italian fishermen at Forster/Tuncurry ('Twin Towns History', SRP 34). It is also there at the micro level in the spirit of individual lines and images expressing communal cohesion, succour and sustenance - for instance the semiotics in the line: 'a light going out in a window here has meaning' (in the very early poem 'Driving Through Sawmill Towns', CP 10 at 11) and the similar sentiment reconfigured years later as: 'an ambulance racing on our backroad/is bad news for us all, the house of community is about/to lose a plank from its wall' ('November: The Misery Cord', in 'The Idyll Wheel' sequence, CP 297 at 298).

'Human systems' are shown in the images of 'live' and 'dead' ('abandoned'), 'new' and 'old' local properties - with their attendant 'known' and 'unknown' stories ('Aspects Of Language And War On The Gloucester Road' and 'Crankshaft') - and the way those properties appear to talk to each other across different poems in Murray's oeuvre, existing as repositories or performance spaces for recounting Murray family and other local - family history and lore. |

[Above] Portrait of Les Murray 3, Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Valerie Murray, 1997)

As noted, the most extensive, single poetic study of Bunyah is The Boys Who Stole the Funeral (1980). In this work the regional 'human system' and its relation to intervening outside influences is based on several components and their opposition: the denizen 'Dunn' family and wider cousins, clan and community - demonstrated for instance in the large local and regional attendance for the digger's funeral; the local politics ('Burning Man' Powell; and Philip Cotton - 'a bastard, but ... one of ours' - lending money to fellow locals); and the 'rupturing' into this rural scenario of 'Athenian' Forbutt senior and Noeline Kampff; and young Forbutt's assimilation into the 'Bunyah-like' human system at the verse novel's end. The identity and cohesion of the community is pointed up in the political polemic of The Boys (the collectivisation of the regional farms and the destructive and demoralising effect of Sydney-centricity: sonnet 107); and the social impact (eg unemployment) which this is demonstrated to have on the rural community. This community absorbs/takes in some outsiders, and withholds itself from/resists others (Kevin Forbutt becomes a 'stayer'; Forbutt senior and the unfortunate Reeby are non-'stayers'. [15])

In addition to the above, alignments to three other key bioregional identifiers can also be noted across Murray's poetry -- though admittedly less intensively: Native flora: Examined in: 'The Fire Autumn' (CP 33); 'The Gallery' (CP 130); 'The Gum Forest' (CP 150); and 'The Edge of The Forest' (CP 115)(specifics of flooded gum, tallowwood etc); 'The Forest Hit By Modern Use' (CP 181); 'Strangler Fig' (CP 372); 'Cockspur Bush' (CP 374)

Geological systems: References to shale, black rock bedrock and to trachyte hills in 'Aspects Of War And Language On The Gloucester Road' (CP 279); 'The Fossil Imprint' (SRP 40).

Bird and animal migrations: 'Migratory' (CP 395); soldier birds arriving in May in 'The Idyll Wheel' (CP 285 at 288) - or indeed, humans placed in the metaphorical framework of a 'Christmas migration' ('the season when children return with their children') in 'The Bulahdelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle' (CP 136 at 138).

Bunyah fauna: In consideration of regional fauna, two animals - introduced and native, respectively - warrant special mention as components of a 'bioregional' Bunyah: the dairy cow, and the flying fox (fruit bat). Both animals function as personal, 'psychic' talismans for Murray to locate himself imaginatively in the home terrain. Lawrence Bourke has succinctly proposed the prominence of dairy cattle's symbolism in Murray's poetry 16: ... [dairy cattle] embody the values of community, domesticity and equanimity, of drawing health from the land ... Drawing upon his dairy background, Murray celebrates the cow and explores a complex network-historical, psychological and physical - which he finds connects people with animals ... [Cattle] describe a circular pattern, a return to Boeotia. Because they are the animals of settlement and cultivation, cattle in Murray's poetry reconcile people with the natural world, with origins and pasts, and in doing so reconfirm a contract with the animal powers ... these cows are guides to a place that will sustain and nourish.

Their significance for dairy families is extended by Murray himself elsewhere, a little more ambivalently 17: [Cows are also] our jailers ... Cows have to be milked twice a day every day, no matter what ...

[Above Left] Krambach-Bunyah Road, Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Paul Cliff, 1997) [Above Right] Bunyah Community Hall, Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Paul Cliff, 1997)

Among a welter of Bunyah poems featuring cattle, the beasts appear most centrally in 'Walking to The Cattle Place' (CP 55) where their presence is both real and physical (depicted straining under fence wires, or standing chest-high drinking in a creek) as well as more symbolic and mythological (emblems of the evolution of civilisation). There is also the simultaneously realistic and symbolic evocation of the bull erupting into the milking shed ('Infant Among Cattle', 'The Idyll Wheel' sequence, CP 298) and, from a dazzlingly different - 'inside' - perspective, the evocation of bovine slaughter told from the beasts' own point of view ('The Cows On Killing Day', CP 384). More marginally, but still potently, the animal appears in the mythological closure to 'The Grassfire Stanzas' (CP 164), and in 'The Sleepout' (CP 238). It is also there implicitly in the childhood and adolescent evocations 'The Milk Lorry' and 'The Butter Factory' (CP 245 and 254 respectively). And (again more marginally) for instance, in Murray's latest collection - in 'A Dog's Elegy' (CAV 46).

As stated, a second local animal with which Murray has overtly identified himself is the flying fox - with a thriving, real world community of its own in the Wingham Brush some 40 kilometres north-east of Bunyah. The creature appears as principal in 'The Flying-Fox Dreaming' (CP 118) and more tangentially in 'The Action' (CP 113) and 'January: Variations On A Measure Of Burns' ('Idyll Wheel' sequence, CP 299) - while 'Exile Prolonged by Real Reasons' (which appeared in The People's Otherworld 58, but was excluded from the Collected) features an oblique symbolic reference to a, significantly, crippled animal. (Coincidentally, the bat's most recent appearance is again 'A Dog's Elegy', where the deceased canine melds with the earth, and is envisioned to 'rise to chase fruit bats and bees'.)

Conversing with the present writer while driving from Wang Wauk Forest into surrounding rolling dairy land, the poet once brought the dual totem images of cow and flying fox together in the remark: 'I think I'm a cow ... but I wish I was a flying fox'. 18

In broader consideration of Murray's depiction of Bunyah's animal life (and again exemplifying his attentiveness to regional specifics), it is instructive to consider again his essay-catalogue, 'A Generation of Changes', which lists a number of animal species in the different categories. (See Table B, following.)

TABLE B: LOCAL ANIMALS LISTED IN 'A GENERATION OF CHANGES'

(AWF 45) (Sample reference to incorporating poems is indicated in square brackets [ ] )

1. Animals 'increased or become prevalent': waterbirds ('dams and waterbirds') ['The Lotus Dam', CP 259; 'Farmer At Fifty', CP 323; 'Dead Trees In The Dam', SRP 18; 'Dry Water', SRP 83; 'The Long Wet Season', CAV 87; 'The Water Plough', CAV 40] king parrots ['September: Mercurial', in 'The Idyll Wheel', CP 285 at 295; 'Dead Trees In The Dam', SRP/ 18; plus note John Hunter's painting on cover of CAV collection] kangaroos ['Layers Of Pregnancy', CP 372; 'A Dog's Elegy', CAV 46] echidnas ['Echidna', CP 381]

[Above] Dead trees in the top dam, Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Valerie Murray, circa 1996)

(Elsewhere, and subsequently, Murray also touches on the arrival, or return, of native animals and birds. See his 'Our Man In Bunyah' piece describing a memorable convocation of black and white ibis circling the farm at the end of one winter, on a mission of 'search and destroy' (AWF 90); he also notes the farm presence of spoonbills, galahs (see heading 3 below), cattle egrets, bandicoots and pademelons, quolls, koalas, peafowl - and a pelican which once visited the top dam. Notable too is his lovely evocation of the grey wagtail harvesting his startled personage of insects on the bulb-lit verandah (AWF 96); and the piece on Cecil Murray's reviving of an electrocuted kookaburra via dunking in a puddle of cold rainwater (AWF 76).)

2. Animals 'decreased or become less common': jersey cows ['a sherry-eyed jersey' in 'Walking To The Cattle Place', CP 55] (Conversely, Friesians appear in the 'become more common' list) pigs (pigsties and pig farms) ['Blood', CP 20] dairy cows (dairies and dairy farms) [numerously evoked, as shown]

3. Animals 'appeared during Murray's absence' (1957-1985): galahs ['Dead Trees In The Dam', SRP 18]

4. Animals 'which vanished' (1957-85): bullock teams ['The Fire Autumn', CP 33 at 34; 'Cattle Ancestor', CP 377; 'The Devil', SRP 90; 'The Gum Forest', CP 150 at 151; associated with Cecil Murray in 'Kiss of The Whip', CP 97]

5. More tangentially, under the heading of animals 'vanished before Murray's time [ie prior to 1938] but still remembered' is a reference to the 'eating of native birds and animals (parrot soup)' [After feeding on tobacco bush, they taste of 'boiled cigars', per 'Aspects of Language And War On The Gloucester Road', CP 279 at 280]

Local fauna - right down to the humble house blowfly - is also a leitmotif in Murray's mini-epic, 'The Idyll Wheel: Cycle Of A Year At Bunyah, New South Wales, April 1986-April 1987' (CP 285). This 20-page meditative transcription of 13 months in the community and on the land is the best single example in all Murray's poetry to date of his bioregional working of the home landscape. Structured impressionistically and by 'monthly collage', it has something of the feel of a farmer's almanac. (See detailed discussion elsewhere.) A second major treatment of the Bunyah animal motif is the sequence 'Presence: Translations From The Natural World' (CP 371 96). About a score of this sequence's pieces are confirmed by the poet as being 'first and mostly inspired by life [at Bunyah]' [19] - evoking animals and plants located (or 'locatable') in his 'spirit country', and based on his experience and minute observation of life there over a 50-odd year period. These lifeforms (both endemic and introduced) are itemised in Table C following - and are cross-referenced to their appearances elsewhere in Murray's poetry. (Murray's identification of the Bunyah context of each is parenthesised as 'LM' beside the items - derived from correspondence, 4/6/1997.)

[Above] Bunyah Environs, Bunyah, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Paul Cliff, 1997)

TABLE C: BUNYAH LIFEFORMS IN SEQUENCE, 'PRESENCE: TRANSLATIONS FROM THE NATURAL WORLD' (CP 371-96)

Eagles ('Eagle Pair', CP 371); (LM: 'I first learned eagle ways at home') cf s 4 of 'Evening Alone at Bunyah, CP 15: 'Deer's [Hill] ... where eagles nest'; and s 4 'The Bulahdelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle', CP 139: 'around the sun are turning the wedgetail eagle and her mate ... they settled on Deer's Hill'

Dogs ('Two Dogs', CP 373); (LM: 'first and mostly inspired by life here') cf 'Farmer At Fifty', CP 323. See most recently the image of the dog in 'A Dog's Elegy'; CAV 46.

Cockspur bush ('Cockspur Bush', CP 374) The bush is evoked as a mini-ecosystem: 'I am lived. I am died ... I am innerly sung by thrushes ... Finched, ant-run, flowered...my shape is cattle-pruned ... my thorns are stuck with caries/of mice and rank lizards by the butcher bird'. The bush also presents in s 12 of 'The Bulahdelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle', CP 137 at 145: 'birds hiding ... in the cockspur canes'

Stone fruit ('Stone Fruit' CP 392); (LM: 'home') cf many references to Bunyah orchards and fruit trees, both active and abandoned ('fruits of the grandmothers')

Possum ('Possum's Nocturnal Day', CP 396); (LM: 'our forest') The animal also features in 'The Widower In The Country' (CP 3): 'a possum ski-ing down/the iron roof on little moonlit claws'; and there is the 'marooned' possum caught out in daylight above the road works in 'Aspects Of Language And War On The Gloucester Road' (CP 279 at p 282). (Most recently, there is the glider possum in 'The Disorderly', CAV 34.)

Dairy cows ('The Cows On Killing Day', CP 384); (LM: 'yes, home') An animal without whose charged presence it is impossible to conceive of Murray's Bunyah poetry. The omnipresent totem cows are presented in dramatically different perspective in this particular powerful and moving piece: an 'end of the line' evocation to the more idyllic ones conjured in 'Walking To The Cattle Place' or the 'totem cows' of 'The Butter Factory'.

Pigs ('Pigs', CP 384) cf 'Blood', earlier (CP 20); (though per LM: 'Geoffrey Dutton's pig farm at Anlaby gave me this one; our piggery was much more primitive') ]

Fig tree ('Strangler Fig', CP 372) (LM: 'very much a feature of all this country of mine') Cf s 8 'The Bulahdelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle', CP 137 at 142: '[mosquitos] drift up the ponderous pleats of the fig tree'

Lyrebird ('Lyrebird', CP 374) The bird absorbs and recycles the sounds of its Bunyah environs: 'I mew catbird, I saw cross-cut, I howl she-dingo, I kink/forest hush distinct with bellbirds, warble magpie gargle, link/cattlebell with kettle-boil ... Gun the chainsaw/screaming woman owl and human talk ...'

Beef cattle ('Cattle Ancestor', CP 377); and Bullocks. The cattle are expressed in terms of Aboriginal (and 'white pioneer') legend: 'Darrambawli is a big red fellow' - 'he initiates his brothers, the Bulluktruk. They walk head down in a line ... You hear their clinking noise in there ... They're eating up the country ...'. And bullocks are associated, of course, with Cecil Murray, ex-bullocky in Wang Wauk forest (cf eg 'the ruins of bullock bell trails' in 'The Fire Autumn', CP 33 at 34; and the 'bullock roads' in 'The Gum Forest', CP 150 at 151).

Grass ('The Masses', CP 382) Moves from naturalistic observation ('We thicken by upper grazing, fatten palely under dung') to the universal ('We calmed cataclysm to green ... Tied in fasces,/dead, living ... No god is bowed to like grass'). Elsewhere, the image of grass is expressed in somewhat Whitmanesque terms (eg the second last stanza of 'First Essay on Interest', CP 166 at 168: 'it becomes a vivid steady state/that registers every grass-blade seen on the way ...'; or in 'The Names Of The Humble' segment of 'Walking To The Cattle Place' (CP 57 at 59), where the Jersey cow 'stays to pump the simpler infinite herbage').

Finch ('MeMeMe', CP 386); (LM: 'home') Firetail finches also occur in 'The Warm Rain', SRP 94: '[settling into] our climber rose'

Raven ('Raven, Sotto Voce', CP 394); (LM: 'home') This evocation of man with gun in the bird's landscape recalls the brooding, bird-shooting adolescent seen in 'SMLE' (CP 49); in s 3 of 'The Bulahdelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle', CP 139; or in 'A Torturer's Apprenticeship' ('He must shoot birds', CP 347).

Migratory birds ('Migratory', CP 395); (LM: 'beaches east of home & elsewhere') There is a strong bioregional context here: 'I am the wrongness of here, when it/is true to fly along the feeling/the length of its great rightness'. cf the migratory soldier birds in 'May: When Bounty Is Down To Persimmons and Lemons', in 'The Idyll Wheel' sequence (CP 288)

Fox ('The Gods', CP 376) (LM: 'but note reference to Shaw Neilson')

Cattle egret ('Cattle Egret', CP 378); also appears in 'Walking To The Cattle Place' (CP 55) and 'Dead Trees In The Dam' (SRP 18)

Horse ('Yard Horse', CP 381) Lawrence Bourke devotes five pages (pp 61-65) of his Murray study A Vivid Steady State to discussion of the significance of the horse image, connecting it variously to the ballad tradition (and its ethos of egalitarianism and community) which Murray values, to the 'Australian Legend', and the First AIF and the Light Horse's demise at the First World War. Murray can also connect it, however, to 'privilege' (the squatter on horseback) or, as in 'The Away-Bound Train' (CP 6), to nostalgia for a past world and era distanced from, or opposed to, modernism and the contemporary city, eg his uncle's horse in 'Crankshaft' (CP 401 at 405). More lyrically, there is the fanciful pony in 'Spring Hail' (CP 8); or the yarn of the foal in 'Joker as Told' (CP 270). Most recently, in a folkloric recollection, the dam scoop is yoked to a working horse in 'The Water Plough' (CAV 40).

Conclusion

|

While not wishing to be excessively dogmatic, this article suggests that it is illuminating to consider Les Murray's Bunyah work in light of the 'bioregionalist' approach to landscape. A broad bioregionalist sympathy might be seen to run across a range of Murray's poetry, prose and other more public statements and positions. This basic empathy is also pointed up by comparing some aspects of Murray's approach with that of the American poet - and avowed bioregionalist - Gary Snyder. The article extended such analysis by aligning specific Bunyah poems to key bioregional signifiers (Table A), by considering Murray's representation of broader elements of flora and fauna in his native district (Tables B and C), by making reference to two particular regional animals (the dairy cow and the flying fox), and by briefly touching on Bunyah's representation of Indigenous history and culture. Thanks are extended to Les Murray. |

[Above] Les Murray (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, year unknown)

ABBREVIATIONS USED in this article

CP - Collected Poems (William Heinemann, 1994)

SRP - Subhuman Redneck Poems (Duffy & Snellgrove, 1996)

CAV - Conscious And Verbal (Duffy & Snellgrove, 1999)

AWF - A Working Forest: Selected Prose (Duffy & Snellgrove, 1997)

AVSS - A Vivid Steady State: Les Murray and Australian Poetry (Lawrence Bourke; NSW University Press/New Endeavour Press, 1992)

ENDNOTES

1. Another modified chapter - on folkloristic elements in the Bunyah poetry - has appeared as 'The Perpetual Dimension: Folkloristic Elements in Les Murray's "Bunyah"', Australian Folklore, no. 15; 2000; pp 200-214.

2. Walter Truett Anderson. Originally quoted from an article, 'The Pitfalls of Bioregionalism', UTNE Reader 14, Feb/March 1986; re-quoted in Simply Living 2:11, p 39.

3. Derived from a table formulated by Kirkpatrick Sale, Simply Living 2:11, p 38.

4. Great River Earth Institute (Transformative Earth Education) website, September 2001. The address is: http://www.geocities.com/RainForest/1624/umvei.htm#umvei (The bioregional information is at: http://www.geocities.com/RainForest/1624/bioreg.htm)

5. Murray has obliquely endorsed this view in correspondence, 4/6/97 - in his expressed attitude to the Industrial Revolution.

6. Interview by Gita Dardick, 1986, Simply Living 2:11, p 39. Snyder, incidentally, is an American writer who Murray read quite early: 'The first [American] I read was Robinson Jeffers, and found my way back from him to Whitman ... I think I was probably one of the first Australians to read Gary Snyder' (Carole Oles, 'Les Murray: An Interview by Carole Oles', American Poetry Review 15:2, March/April 1986, 28-36 at p 32; quoted in Bourke, 1992, at p 49).

7. Clarrie the ex-Digger is returned for interment there; 'citified' Kevin Forbutt re-finds his 'proper place' among his 'mother's people'; irretrievably citified Reeby, 'lost, and without place', tragically dies there.

8. Dardick, Simply Living 2:11, p 39.

9. Murray, speaking of Dick and Lily Harris's old house at Bunyah. Appendix A, item 9. 'City folk' acquired, and made a good fist of rehabilitating, the dwelling.

10. Murray's essay 'Eric Rolls And the Golden Disobedience' (AWF 148) very positively reviews Rolls' A Million Wild Acres (1981).

11. Murray observes that, like many long-established Bush families, his has Aboriginal relatives (eg 'I'm related to a lot of them': ABC Radio interview with Margaret Throsby, 11 Feb 1997). He is perhaps closest to his Aboriginal cousin, Vicki Grieves (Appendix A, item 3).

12. The Paperbark Tree: Selected Prose, Carcanet, Manchester, 1992, pp 71-99.

13. In correspondence, January 2001, Murray revises this earlier attitude: 'now I know this is wrong. Land was open in Aboriginal times, & house etc sites are ineffaceable. Dug soil never returns ...'

14. Simply Living 2:11, p 39.

15. By extension, Noeline Kampff too may possibly become a (temporary?) 'stayer', taking up with 'Burning Man' Powell; and Jennie Dunn seemingly self-exiles herself from her native community, by her act of scalding Noeline Kampff's face.

16. Lawrence Bourke, A Vivid Steady State, at pp 66 and 67.

17. Soundtrack to Don Featherstone's film (videotape), Les Murray: The Daylight Moon, ('Videos on Australian Writers Collection'), AFI, Sydney, 1991.

18. July 1997 (Interview; Appendix A, item 27).

19. Interview, 1997; Appendix B, p 3.

About the Writer Paul Cliff

|

Paul Cliff has published three collections and has been included on the CD Australian Poetry: Live at Chats (Geoff Page, 1999) and in anthologies (Mattara, Poet's Choice, Footprints on Paper) and has also published book reviews. For the past 20 years he has worked as a book editor (McGraw-Hill, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich) and magazine editor (Simply Living and Geo). He currently works in the National Library of Australia's publishing division, where his compilation The Endless Playground (on Australian childhood, based on the Library's Oral History, Pictorial and Manuscript Collections) received honorable mention in the Centre for Australian Cultural Studies Awards 2000. He's also compiling from the Library's Manuscript Collection a small poetry anthology reflecting Australian childhood experience, to accompany that book. Paul's experimental piece Deadline: A Manual for Hostage-Taking won the Canberra Playwright's Competition for 2000, and was produced by Canberra Rep Fringe. He has been a runner-up in the Robert Harris/Ulitarra Poetry Competition. Paul is completing a text on Les Murray (extending a Masters thesis focused on the creative process in Murray's use of 'Bunyah' landscape, iconography, and sub-themes. |

[Above] Photo of Paul Cliff by Skye Blomfield, year unknown.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.6 (September, 2002) |