CATCHING A TRAIN TO INTIMACY: LANDSCAPE IN BRENDAN RYAN'S POEMS

By Cassie Lewis

[Above] Looking northwest to the house and Mt Warrnambool in the distance (Photo by Brendan Ryan, circa 1998)

One afternoon in Collected Works bookstore I asked after Ted Berrigan's "So Going Around Cities". Brendan Ryan was browsing the shelves and offered to lend me his copy of this 'New York School' classic. We soon became friends.

'New York School' styles sit well with some of Ryan's modes as poet: localism, use of humour, everyday happenings and popular culture references and the desire to know his own surroundings. His sense of community, too, has commonality with this tradition, in as much as his landscapes are peopled.

Ryan's concerns as a poet are distinctly Australian, however, and his influences many.

|

Like his contemporary, the late Philip Hodgins, he grew up on a dairy farm though he now lives in Melbourne. He straddles the boundary between urban and rural Australia, writing with empathy about each, rather than romanticising one over the other.

His poems uncover stories without the pretence of capturing 'truth'. Thus one constant is a cinematic awareness of change[2] and of his own subjectivity as author.

* * *

|

[Above] Photo of Philip Hodgins courtesy of Duffy and Snellgrove, 2002.

I'll define that to which the tricky word, 'landscape', in my article's title refers: the term is often used to denote physical descriptions of rural settings, but my usage of it will be more open-ended.

I'd qualify that former usage with the following factors. Self-evidently, perception is never transparent, so that our view of the land is subjective, mediated by social forces. Therefore any claim to transparent description of 'rural truth' becomes suspect.

Furthermore, cityscapes are no less 'of the land' than rural areas. Many poets are able to write about both city and country with equal dexterity, so that 'landscape poet' as synonymous with 'rural poet' becomes a loaded category of limited use.

[Above] Vickers Rd - our farmhouse is on the right. We own land on both sides of this road. (Photo by Brendan Ryan, 1999)

[Below] Looking northeast to the farmhouse where our relief milker lives (Photo by Brendan Ryan, 2000)

Another factor is the interdependence of form and content. Traditional definitions of 'landscape poetry' seem like an ingredients list presuming more or less traditional formal techniques - whereas experimental poetries deal with the land too, as the Pacific Region magazine Tinfish, edited by Susan Schultz, demonstrates.[3]

A related matter is the anecdotal equation in Australia of 'landscape' not only with the rural but with a mostly male group of contemporary poets, led perhaps by Les Murray - which forgets important female writers like Louise Crisp.

In 'Untimely Meditations', Ken Bolton amusingly - and perceptively - points out another potential limitation of traditional notions of 'pastoral'. That is, the assumption that the rural areas are more authentically 'Australian' than the cities. Here is an excerpt that Lee Cataldi also used in an essay in Overland in 2000.[4]

|

Les assured us the Country was

'more Australian'.

It was different. I could see that.

So I could see how it

might be 'better'.

Well, actually, I couldn't

but I could see

that someone might say it.

Though, really, I wish they wouldn't.[5] |

[Above] Mt Emu Creek which borders part of our farm (Photo by Brendan Ryan, 2000)

When I say 'landscape', then, I mean something quite diffuse: physical habitats as seen through the prism of inexorably human concerns.

Environmental destruction by humans has cast suspicion on rural idylls and consideration of social problems - Aboriginal dispossession looming largest among them - reinforces an urgent need for more dynamic tactics in art. I share with others the notion that "to love the Australian country ... includes a responsibility towards it", [6] and that this engages poets in "resistance to marketing the world as it is when in fact it increasingly isn't".[7]

Such a position presumes that art should be relevant to contemporary life, but opens up the issue of methodology to a spectrum of possibilities beyond simple political statements about the land. In current Australia poetry, these range as widely as John Kinsella's 'anti-pastorals', Lisa Bellear's emphasis on local community, Ken Bolton's humorous urban commentary or Jill Jones' cityscapes. Seen thus, landscape becomes a highly mobile category - an accent in contemporary work, rather than a roll-call of poets.

Insistence on the local is one connective strand in current landscape poems, a way of saying 'this is who we are, where we are, these are our concerns'. The poets listed above share this focus, in their different ways, and it works as an assertion of change, as a source of possibility as well as loss.

At its best localism eshews both the "ludic unreadability" sometimes associated with postmodernism on the one hand, and "grand transparency... claiming a legacy of balance, blood, earth and 'truth'" on the other.[8] Thus a postmodern awareness here inflects social realism, and vice versa.

* * *

Brendan Ryan's poetry is another example of this balance. Most, if not all, of his poems are physically anchored to place. For clarity's sake, I'll use a fairly crude division of the work into 'rural' and 'urban', based on setting. In the poem 'Return to the Western District'[9], from his first chapbook, he describes the arc much of his work follows.

Each time I return

certain objects are caught: green algae in a water trough

and later concludes 'all I can hear are sirens, Punt Rd traffic'. Thus the writing moves between rural and urban concerns. There's awareness of subjectivity and contingency implicit in such descriptions.

|

The author does not claim to 'catch' all 'objects' in his gaze, and city 'sirens' become a palimpsest made by memory upon the present.

Ryan's focus is on cinematic instances within landscapes: a useful method for combining realism with postmodern awareness. Martin Harrison, talking about landscape in his own work, has emphasised 'intersection and situatedness', noting that 'cinema always locates the angle'.[10]

Without wishing to argue by analogy, poems like Ryan's uncollected sequence, 'Naming the Paddocks', do locate protagonists within specific film-like contexts, rather than adopting an all-knowing tone. The tone is instead that of an involved and empathic observer, as in 'Lake Mungo'.

The water container

is beginning to swell,

something more than light

is falling against us.[11]

Subtle details like the swelling water container help portray the landscape as dynamic and acted on and within by its inhabitants - as it is in fact - rather than static. |

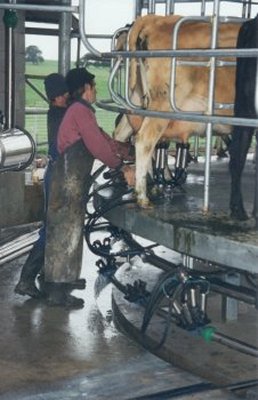

[Above] Ryan's brother Jack and Ryan putting on the machines (Photo by Alison Girvan, circa 1997)

There is room for awe, beauty and warmth in such 'pastoral' poetry, though not for romanticism. Many of the images are serene. In 'Lake Mungo' Ryan writes of '... shadows/ turning ochre, lunar gold', and includes these lines:

The walls of China tremble

inside three rolls of film,

their history of bones

recording the countours

of a landscape eroding,

a sky flaming

over a saltbush plain[12]

Images of 'the walls of China' become more poignant due to the 'eroding' environment in which they're witnessed. For me this proves that beautiful landscapes can be evoked without recourse to rural idylls.

[Above] Cows leaving the dairy (Photo by Brendan Ryan, 2000)

Inescapable differences between city and country become apparent in Brendan Ryan's work. Despite this age of advanced communication and rapid travel, the binary remains relevant as lifestyles in each place are 'too different to be the same'.[13] Such differences are well accepted and range over most aspects of life - employment opportunities, for instance.

The themes of leaving and returning to the country - and the impetus behind journeying in both directions - highlight such differences strongly. In 'Why I Am Not a Farmer', Ryan writes

Mostly it is the talk of leaving

that keeps you in the country-[14]

Similarly, 'The Paddock Behind the House'[15] includes the phrase 'who to talk to, when to leave'. There is sadness in such lines, as though country life were somehow untenable for those characters. Another new poem, 'The Paddock with the Big Tree in It', starts with the simile

like an anchor rattling overboard

she turns away from her mother [16]

so that a young woman's sense of isolation from her upbringing is compassionately portrayed. The poem concludes with these lines:

She leans into wood

electrified as prayer

Youthful energy is wonderfully evoked by this comparison, along with a certain loneliness as the woman stands in a doorway looking outside. The use of simile is an effective device here as in many of Ryan's poems - and I'll discuss this later.

Brutal depictions of farming life that recur through the work serve as one 'reason to leave'. Frequently violence to farm animals is the site of brutality - as in 'The Kill"[17] , a poem describing the slitting of a sheep's throat. Such events come across as a tough constant in farming life.

There are parallels here with some of Philip Hodgins' work, including 'Dead Calf' and 'Shooting the Dogs'[18] - though Hodgins is distinctive in that he often interprets farm violence through the cancer affecting his own body.

|

Dry humour is sometimes used to temper the gravity of violent scenes in Ryan's poems, thus rendering them more memorable for me, as in 'The Blessing'.

... my father concentrates

on saving this cow

by kicking it in the ribs,

which is a type of country blessing.[19]

An undercurrent of human-to-human brutality runs through his descriptions of country life too. 'The swollen cheekbones/ of a neighbour's wife'[20] appear as a further reason to leave in the poem 'Why I Am Not a Farmer'.

The author doesn't separate himself from rural violence, and sit in judgement, but rather sees himself as unavoidably involved, often through memories of childhood events.

Ryan's 'A Job to Do', about putting down a calf, includes the line: 'at ten I know what it like to kill'. Similarly, these lines from an uncollected work:

I threw a lump of wood

in my brother's face[21] |

[Above] Carrying a new calf (Photo by Alison Girvan, 2000)

Violence towards the land is another undercurrent in the rural-setting poems. Judith Wright's work often deals directly with environmental issues, in poems such as 'Flame-Tree in a Quarry'.[22] By contrast, Ryan tends to more oblique commentary. Typically his descriptions focus on a site of loss, where 'the bush we don't see closes in like memory.'[23] A poem dealing with the aftermath of a bushfire illustrates this point.

The past is scorched, but its heat

rises through my workboots.[24]

Nonetheless the author alludes to the attractions of country life. The imaginatively titled 'Catching a Train to Intimacy'[25] proves one example when the author notes with some relief that 'the Literary world stops at Spencer Street'. Some sense of a larger canvas is hinted at when country people 'look away, distracted by the wind'. Similarly the line 'like a babysitter the city releases you' hints at freedoms discovered in the return to rural life.

As a whole the work conveys a deep ambivalence about these different worlds - city and country - that holds protagonists on a roundabout between the two.

Ahead of us, city buildings

we swear we'll never return to

again and again.[26]

* * *

Ryan's work is assuredly more subtle than these thematic considerations have so far suggested. The restlessness pervading it makes static or all-seeing idylls impossible, and gives a keen edge to his style. In 'The Gap' Ryan notes

Like a ring-in who can't sit down

I return to the streets of the town I was born in.[27]

A combination of empathy and estrangement is at play in such poems about country life. He lightly mocks the cliched city view of the country towns as 'a bayside suburb, a sit-com, a getaway idea!',[28] alluding to his own deeper understanding.

'The Benefits of a Rotary Dairy' demonstrates this understanding. At twenty-nine stanzas, it is the author's longest published poem to date. Ambitious in scope, it successfully ironises its subject matter.

[Above] Cows in the rotary dairy (Photo by Brendan Ryan, 2000)

The effect is cumulative, and almost defiant in its chronicling of small inflections of rural life. Lines are tighly compressed - and at first seemed to me overly formal in tone - but rewarded closer reading. Here's a short quote.

Religious discussions are no longer possible.

The roar of the engine is absolutely modern.[29]

* * *

I'll talk a little about Ryan's technique. He generally writes in free verse, with regular stanza structures, though he has experimented recently with pantoums and with minimalist grammar.[30] His more recent poems demonstrate a high degree of technical skill. The following use of enjambment is expert.

Most nights I walked down

a road of burning trees

into a landscape of light,

slanting rain[31]

Here readers are offered dual senses of a 'landscape of light', and one of rain. Consider, too, this skillful enjambment in a city poem, 'Ode to Joeys', from the chapbook Mungo Poems.

It's not who you are

with, were or could be.[32]

|

Like many contemporary Australian poets - John Forbes, Pam Brown and S.K. Kelen, to name a few - Ryan uses popular culture references as touchstones of modernity in his poems, or, more precisely, refers to them whenever they seem relevant, rather than deeming them somehow unfit for poetry. In his case this mostly means references to music, as in 'Shakespeare Didn't Play Guitar',[33] which portrays a rural adolescence through the lens of favourite bands. |

[Above] Photo of Brendan Ryan by Alison Girvan, 2000.

Like Philip Hodgins, the subject of his English Honours thesis, Ryan tends to use simile more than metaphor. Just one example out of many is below.

Like a kangaroo ramming its head

against a chicken-wire gate

we rush to escape

before the rain turns the road

to slush[34]

For all writers there are moments when one's skill falters and, arguably, most of Ryan's occur in urban poems. The pace of these poems feels slower than the events described, as though the speed and fractured imagery of the city required more adjustment than was made. In 'Lines to Helen'[35] the long vowel sounds of 'meal' and 'deal' slow things down - so that other lines like 'cars are bullets'[36] seem too fast. The result is that the tough tone of these poems feels unconvincing sometimes. However, most end with strong lines. For example:

Frayed and intellectual

you peel off like a VB label[37]

Additionally, later city poems indicate a growing ease with this alternative locus for his work, as in 'Argyle Street' where

changes

sweep in from the bay

the way a memory leaves you in its wake.'[38]

* * *

Something fascinating is happening as Ryan's work progresses. It's as if memory and the present day were combining to make fresh possibility. Judging from the poems so far, this possibility allows 'hidden' narratives to be brought to light.

I had my first inkling of this when the author showed me his poem 'Country Man in a Flat'. As the title suggests, it is a character study of a man who has just moved to a city flat and is coping with culture shock. The sense of a man caged comes across.

just himself staring between fence posts

at two gnarled pine trees clutching the sky[39]

|

Because the protagonist draws rural concepts of space onto an urban flat, one gets a sense of past and present locations colliding.

Further examples of the trend to intersection are found in poems like 'Country Parents in Town'.[40] The cover of 'Why I am Not a Farmer' corroborates with a photo of a cow superimposed over a city skyline.

Throughout Ryan's work there are references to memory's connection to landscape which push him into new artistic territory. |

[Above] Cow and calf. 'The Bush' is behind them and forms a boundary to part of the farm (Photo by Brendan Ryan, 2000)

As for Judith Wright, 'stories' take on haunting importance. In 'South of my Days' Wright includes these lines:

South of my days' circle

I know it dark against the stars, the high lean country

full of old stories that still go walking in my sleep.[41]

Similarly, in Ryan's work memory is etched upon the present day. Consider 'May Day Reunion' and these strong lines.

The shock of old faces

tightened by cacti and a third balcony view of warehouses

keeps us talking

or the moon drifting over a paddock of oats

or some such history we cling to[42]

Memory is written over the present, but the histories it offers are 'unstable'.[43] There's often a sense of rupture, frightening yet latent with possibility. The uncollected poem 'Tower Hill' demonstrates this.

I struggled to glimpse the lake through the trees.

I was looking for a rupture,

a tearing in the flow of my family stories.[44]

The author seems to be looking for ways to make memory align with the present day and to discover the unspoken realities of rural life. This has implications for questions of land ownership, and the suppression of Aboriginal history.

An Aboriginal history is allowed

and not talked about. Who owns the stories

the sloping caldera slips into?[45]

A reaction against enforced silence seem part of the urge to discover 'other' pasts, as though there were terrible truths hidden in the landscape,

the terrible cries

we were not allowed to hear[46]

This drive towards deeper understanding seems a source of artistic possibility for the author. The new series 'Naming the Paddocks', consists of character studies set in the context of farm lands.

[Above] Milkers (cows) in a strip-grazed paddock (Photo by Brendan Ryan, 2000)

Most of the poems are strong and quite compressed. Perhaps they are an answer to Philip Hodgins' challenge in 'Question Time', transcribed below.

In this country

the true test of the imagination

is being able to name a paddock[47]

In the new work Ryan makes linguistic jumps that illuminate both the subject matter and his own growing skill. 'Broken Sleep' is one example, intimate in tone, that shows how places are sometimes more dynamic than memory.

It makes you laugh

that something we spend an hour walking to

doesn't exist[48]

Such developments make the omission of Ryan's poems from both of the recent local anthologies - 'Calyx: 30 Contemporary Australian Poets' and 'New Music' - seem unfortunate. However, I hope this article does not feel like a prescription and that it invites others to explore that dynamic category, 'landscape poetry'.

*******

[Title] Brendan Ryan, 'Catching a Train to Intimacy', uncollected poem

[2] Martin Harrison, 'Poetry and 'Nature'', 5 Bells, Summer 2001

[3] Rob Wilson, 'From the Sublime to the Devious: Writing the Experimental/ Local Pacific', Jacket 12, July 2000

[4] Lee Cataldi, 'Contemporary Australian Poetry' in 'Overland' issue 159, 2000, p 38

[5] Ken Bolton, 'Untimely Meditations', Wakefield Press, 1997, pp 37-38

[6] Gig Ryan, 'Uncertain Possession: The Politics and Poetry of Judith Wright', Overland, April 1999

[7] Peter Minter, 'A View from Now: here: Writing Nature in Contemporary Poetry', Five Bells, Summer 2001

[8] Rob Wilson, 'From the Sublime to the Devious: Writing the Experimental/ Local Pacific', Jacket 12, July 2000

[9] Ryan, "Why I am Not A Farmer", Five Islands Press, 2000, p 30

[10] Martin Harrison, 'Poetry and 'Nature'', 5 Bells, Summer 2001

[11] Ryan, 'Lake Mungo', 'Mungo Poems', Soup, 1997, p 5

[12] Ryan, 'Lake Mungo', 'Mungo Poems', p 6

[13] Poetry Espresso interview with Ryan by Cassie Lewis, February 2002

[14] Ryan, 'Farmer', p 32.

[15] Ryan, uncollected sequence 'Naming the Paddocks'

[16] Ryan, uncollected poem, 'The Paddock with the Big Tree in It' in the 'Naming the Paddocks' series

[17] Ryan, 'Farmer', pp 31 (printed as 'The Killer')

[18] Philip Hodgins, 'New and Selected Poems', Duffy & Snellgrove, 2000

[19] Ryan, 'The Blessing', in 'Farmer', p 5

[20] Ryan, in 'Farmer', p 32

[21] Ryan, uncollected poem

[22] Judith Wright, 'Five Senses: Selected Poems', Angus & Robinson 1978, p 48

[23] Ryan, 'Naringal Landscape', uncollected poem

[24] Ryan, 'Morning After', in 'Farmer', p 13

[25] Ryan, uncollected poem

[26] Ryan, 'Broken Sleep', uncollected poem

[27] Ryan, 'The Gap', uncollected poem

[28] ibid

[29] Ryan, 'Benefits of a Rotary Dairy', in 'Farmer', p 25

[30] For example, an uncollected pantoum 'Lament for Piano Accordian' and the uncollected 'The Fire Tree Paddock' from the 'Naming the Paddocks' series

[31] Ryan, 'Late Country', 'Farmer', p 14

[32] Ryan, 'Ode to Joeys', 'Mungo Poems', p 12

[33] Ryan, uncollected poem

[34] Ryan, 'Lake Mungo', 'Mungo Poems', p 6

[35] Ryan, 'Lines to Helen', 'Farmer', p 17

[36] ibid

[37] Ryan, 'Poem', 'Mungo Poems', p 8

[38] Ryan, 'Argyle Street', 'Farmer', p 18

[39] Ryan, 'Country Man in a Flat', 'Farmer', p 22

[40] Ryan, 'Country Parents in Town', 'Farmer', p 20

[41] Judith Wright, 'South of My Days', 'Five Senses: Selected Poems', Angus & Robinson, 1978, p 15

[42] Ryan, 'May Day Reunion', 'Farmer', p 19

[43] To paraphrase from Ryan's 'The River Flats', an uncollected poem

[44] Ryan, 'Tower Hill', uncollected poem

[45] ibid

[46] ibid

[47] Philip Hodgins, 'Question Time', 'New and Selected Poems', p 17

[48] Ryan, 'Broken Sleep', uncollected poems

Notes on the Sources

Some of the sources I've cited can be found online at the following URLs.

1. Articles by Martin Harrison and Peter Minter at the '5 Bells' website

http://members.ozemail.com.au/~poetinc/5%20Bells%20sum%202001%20Forest%20of%20Mirrors.htm

2. Gig Ryan's article on Judith Wright is reprinted in Thylazine

http://www.thylazine.org/archive1/thyla2b.html

3. Rob Wilson's article is in Jacket 12

http://www.jacket.zip.com.au/jacket12/wilson-p-pomod.html

4. The uncollected poems, 'Shakespeare Didn't Play Guitar' is online in Cordite, issue 8

http://cordite.org.au/09/ryan,shakespeare.asp

5. Similarly, 'A Job to Do' is online in the 'Overland' supplement to Jacket 16

http://www.jacket.zip.com.au/jacket16/ov-ryanb.html

6. Both of Brendan Ryan's collections can be ordered online. The pamphlet, "Mungo Poems', can be ordered at the Soup website

http://www.netspace.net.au/~cgrier/soupabout.html

7. 'Why I am Not a Farmer' is available through Five Islands Press at

http://www.5islands.1earth.net/

8. The interview I conducted this year with Brendan Ryan can be accessed through the archives of the Poetry Espresso discussion list, at http://www.topica.com/lists/PoetryEspresso

It will also be reprinted in a forthcoming issue of 'Famous Reporter'

All photos and uncollected poems are courtesy of Brendan Ryan, and I thank him for his assistance.

(Ed's Note: Thylazine does not condone any form of animal cruelty inherent in the Australian Dairy Industry or other farms where animals are exploited, harmed and murdered for human profit or otherwise. This article has been published in order for us to understand the perspective of an Australian poet, Brendan Ryan, who was raised and operates in these rural environments and how this influences and impacts the form and content of his poetry.)

About the Writer Cassie Lewis

|

Cassie Lewis was born in Papua New Guinea in 1974. She has been publishing her poems widely in Australian magazines and newspapers since 1995 and has also had work published in New Zealand and the U.K. In late 1997 Soup Publications released her chapbook, Song for the Quartet. Her first book, Winter District is due from 'Potes and Poets Press (USA) late in 2000. Little Esther will be doing a chapbook called 'High Country', also in late 2000 For now, her work can be found in back issues of Meanjin, Southerly, Otis Rush, The Age's Saturday Extra, JAAM (NZ), P.N. Review (UK), Heat and Overland. |

[Above] Photo of Cassie Lewis by Colin Rhodes, 2000.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.4 (September, 2001) |