SIGHTING

By John Kinsella

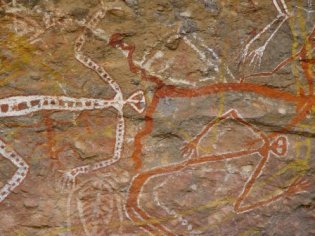

[Above] Rock Art #2, Ubirr Rock, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

The Duplicity of English, and of the English-language Poem in Southwest Australia

In March 2001, at the beginning of the Southwestern Australian autumn, I sighted a thylacine in the Avon Valley district during a visit to my home from America. Realising few would believe me, and that logic dictated I should doubt this sighting and interpretation myself, I suppressed the desire to discuss the issue at length. Almost ten months ago I started writing this essay, only to end up scrapping it after a few paragraphs. Maybe it was simply a case of transfer interrupted. I have been resisting a return to the text because of the need to feel an increase in doubt, to foster an environment of scepticism. Distance is a way of testing credulity.

In reconfiguring the experience, a number of issues became paramount in terms of both the articulation of the moment of contact, and what its significance might be. Always trying to find a language that might express my respect for indigenous claims to custodianship of the land, I considered how easy it is to conflate issues relating to extinction of animals and plants, to the decimation, even attempted genocide of a people/s. To reduce or even consider such an analogic model is insensitive and destructive, but the ease with which such a comparison might be made became my concern.

This essay is an attempt to bring contradictory and disassociated reflections and implications into play, and is a critique of the role of invader, commentator, and self in the processes of occupation and exclusion. The Avon River is the unifying thread, and its flows - now polluted with chemical fertiliser, spray residue, outbreaks of blue-green algae, and salinity - feed the Deleuze and Guattari-like body without organs, illuminating the corpse by the suggestion of functional internal organs, that are really in terminal decline. The sighting of a thylacine is an event in itself, but also symptomatic of my own limitations of perception, of the need to create a unified self and measure the field of occupation - of all human interaction with place. The guilt of non-indigenous Australians collides with their wish to correct wrongs and simultaneously belong, all of which sadly weakens their ability to recognise intrusion as violation. The thylacine is like a marker moving across the grid-work of 'settlement', across the title deeds of ownership.

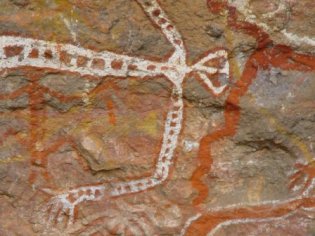

[Above Left] Dingo #6, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001. [Above Right] Dingo #7, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

The signifying event was the sighting of an animal along the Avon River that bore a distinct resemblance to the now-almost-mythical thylacine - last seen alive in Tasmania in the 1930s, having been hunted to near-extinction shortly before that. Australia over the last two hundred years has become a land of extinction and attempted genocide, which is not to say there weren't extinctions before this, but surely not with such systematic and 'artificial' application. And the linking of indigeneity with the extinction of native animals and plants is something that no amount of guilt can rewrite. The association of blackness with darkness/corruption/evil by European writers was evident in settler/invader literature from the earliest ballads, and by the mid to late eighteenth century had become part of the clichéd empire-speak that made subject and object interchangeable, with the only externally available unified voice being that of white authorial edict. In the Western Australian poet Henry Clay's poem "Two and Two" from his volume of poetry Two and Two: A Story of the Australian Forest: with Minor Poems of Colonial Interest (Perth, 1873) [i] , we read:

'O, the black rascal never said a word,

But looked as pleasant as a native-dog

Down-ridden with a lamb between his teeth;

And sneaked along to cover the Bush:

Then, turning suddenly, looked back on me,

And shook his supple arm, and lingoed out

A guttural hate-song,-angry recitative,

That closed with a wild yell;-so turned about,

And like a black snake thro' the thicket slid,

And vanished into darkness.' (64)

The lamb is not just the child of imperialism, Christianity, and righteousness, but also the replacement landtext for territory, landscaping. Without denying the land-management interpretation of fire-stick farming, we can say that the specificity of measurement and calibration, of breaking up land into zones of possession, undid the custodial relationship to place, the organic relationship of self and community to space. The renaming of place is a tangible inscription of reterritorialisation, but it's the remeasuring and apportioning that dictate total exclusion. It's a combination of verbal and mathematical language displacement: a language of exchange, of economics. Indigenous people 'owned' in a way that crown law negated or ignored, but their presence in a particular zone indicated connection. They were removed, and it was not until Mabo that terra nullius was overturned in law.

|

The thylacine ate sheep so it was eliminated. The presence of photographs, drawings, and preserved body parts (DNA revival tropes), does not delete the law of profit ('survival' and improvement) that led to its extinction in the first place. It remains to be rediscovered so it can be made extinct again.

Boustrophedon entails the line of text that is the furrow. Poetry written by the non-indigenous Australian - even deploring occupation - is the blessing of the field, the paddock, the roads, the farm houses. The control of language implied in the creation of the poem (no matter how "deranged') becomes an attempt to roll back the darkness, to 'illuminate' the Bush, position the rural as desirable other. It is seductive and fetishistic.

The lamb of the poem is sacrificial and stoical and made to be eaten. It is the sacrifice by the settler for his beliefs, for his sense of right. The native dog is a foul offshoot of the Fall, a violator that makes the landscape anything but Eden (the settler has to work hard to reclaim the Eden that's buried beneath the pollution), and consuming the cultural lamb is pollution, invasion, and murder. |

[Above] Dingo #2, Bruce's Dingo Farm, Castlemaine, Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1994)

The reality of colonisation is inverted. The scenario is set on the goldfields, with 'black Wallace' one of two thieves trying to steal the takings of a pair of settler lads who've lifted themselves beyond their limitations (in one case, physical impairment and loss), to make good by their own hands, to test their luck.

The codes of exploitation and gain are confused, as much as the animal and human, the extinction and genocide, sacrifice and murder. It is against such code-scrambling that the extermination and potential rediscovery of the thylacine should be seen. The use of "guttural hate-song", the suppression of language through inarticulacy and inaudibility, emphasise the removal of cognitive privilege, and thus 'equality' and self-determination. The language of abuse to animals is transferred. It's an expression of disgust and ownership; a fetishisation into language to enhance the value of 'English' or Western language generally.

The poetry of the body: the ceremonial markings, initiation scars - a written language - are buried beneath text. Text is occupation. The painting of the body - ornament or decoration - is the sign; the meaning of the sign differs between communities. The totem animal of an individual human three thousand years ago might have been a thylacine, and the spirit conjoined with its human counterpart. The language is written in the stripes on its flanks. In seeing the supposedly extinct animal I potentially became its preserver - its exact location a secret.

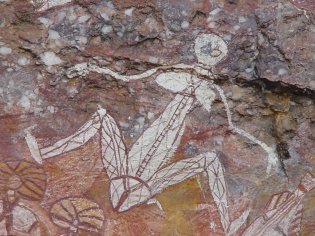

[Above Left] Rock Art #3, Nourlangie Rock, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001) [Above Right] Rock Art #4, Nourlangie Rock, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

There is evidence of thylacine presence on the mainland, though it's suggested there may not have been large numbers for thousands of years, and that it vanished about 3000 years ago. Maybe the biology of the creature goes some way toward explaining this, or maybe, as some might argue, it was in retreat from an evolutionary perspective. A marsupial dog, the male had a so-called rudimentary pouch, and though dog-like in appearance it is often called the Tasmanian Tiger or Tasmanian Wolf - its striped flanks giving it a superficial resemblance to the tiger in particular. The other biological distinction was a massive gap between jaws. Thylacines were 'sheep killers' (lamb slaughterers), and were extinct by 1936. In 1993 a thylacine was supposedly sighted in Western Australia on a road in the Southwest. In 2002 I sighted a thylacine, had my mother photograph its tracks, mentioned it to a couple of people, was predictably mocked, and then determined that I'd keep it to myself to protect the animal and to allow time to increase doubt. What fascinates me is why people have such an investment in this now quasi-mythical animal existing, or not existing. To 'own' something supposedly lost comes with its own language of ego and property. If it existed in numbers and was killing sheep there'd be a cull, no doubt, as was the case in Mount Barker with a rare native cat that was culled by state wildlife officials because 'local farmers had complained'. At least part of the answer to this can be found in the racism implicit in the Clay poem as it continues:

"Then I fear

The fellow means some mischief. He can work

As well as any whiteman, and 'tis said

He's half a king,-and so he got his name:-

But he's as stubborn as a forest boar,

If you but anger him…" (64)

The subtext is an opposition to Scottish nationalism by the English identity of the lyrical narrative voice, and the equation of 'black Wallace' with William Wallace and a war of freedom works ironically in both directions. It is a negative, and intended so, but also one of begrudging respect - almost suggesting that the white prospectors rely on the 'other', the semi-regal Aborigine, to validate their identity. The young men go forth to be tested and prove themselves against ... The animalisation and potential bite-back of the 'enemy' places him on the level of the semi-mythical beast that must be defeated for the wealth (the treasure, the quest totem) to be released. The discovery and defeat define self, community, and spiritual power.

The stanza finishes with:

'...I had my task

To win and master him; and after all

He left his work, with Max, because they heard

I could not follow them'- (64)

There is another inversion here. The taming of the beast, but also the bête noire factor of the untameable - the inability to track the tracker [ii], that is, the stereotype of Aboriginal functionality in the landscape - the use to the settler. In the same way that we assume the native cat and forest boar (introduced species, or transcription of Euro-motif) are there to be defeated, punished, or captured, we assume the capturing, in the end, of the Other. The taming of the dark side of self. The need to see the thylacine, feeding the side of ego that extinguishes threats to territory, fits the same racist discourse. The language of racism is the language of oppression to animals. And in the same way that the non-vegan excuses the use of animals out of necessity, so too does racist discourse excuse the need for hierarchies and suppression of individual contrary identity.

The Sighting

|

I have said, and I say, that I have a spiritual connection to the land. I do not mean a Nyungar spiritual connection; I mean a spiritual connection mediated by the rejection of Christian religious orthodoxy, the spiritual environment of the upbringing. Animals come to me because I do not eat them. That's what I think. So, there are cross-pollinating relationships with place. This is countered by my need to not-belong, to recognise the undercurrent of ownership, of property, that informs my sense of place and displacement.

As an anarchist I reject individual ownership; but what constitutes the community of occupation? |

[Above] Dingo #4, Oodnadatta Track, South Australia, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

Adam Shoemaker, in Black Words White Page: Aboriginal Literature 1929-1988, (St Lucia, 1989) writes of Les Murray: Murray is intrigued by, and concerned with, White Australian myths about Aborigines and with the mythology of the Black Australians themselves. He appears far less interested in portraying Aborigines as people, or in reflecting their characteristic rural or urban speech patterns. For example, his poem "Thinking About Aboriginal Land Rights, I Visit the Farm I Will Not Inherit" is a personal evocation of the pain that the dispossession of land can cause:

By sundown it is dense dusk, all the tracks closing in.

I go into the earth near the hay shed for thousands of years.

Here it is implicit that Murray's feeling for the farm which he will be denied is akin to the sense of loss which has afflicted Black Australians confronted with white encroachment into their continent. He feels very intensely that White Australians view their land as far more than an investment: "It's bullshit to say that 'property' is the concept that whites have for land; I couldn't live in another place from where I've come from."

While it is true that White Australians have developed a real and heartfelt feeling for their sometimes unlovely land since 1788, Murray's reference to 'thousands of years' pushes the parallel too far. The sense of belonging of which he speaks is of a different order of magnitude to the sense of being owned by the land, which is the traditional Aboriginal concept, with all the sanctity of religious veneration ... (199).

I have heard Murray's feelings reflected by many non-indigenous land-owners who have lost their land through inheritance, economic disaster, or ill-health. The problem with this is obvious, given the dispossession that allowed or led to their possessing the space in the first place, but there's also a problem in Shoemaker's language, a language that speaks as much in terms of occupation as does the linguistically evasive language of Murray's poetry.

|

The conflict between being owned by the land - an expression of convenience used by English-language critics (of whatever cultural background; the use of the language itself will always brings its own subjugation and compliance) - and an expression like "confronted by white encroachment into their continent" is the language of the defensive imperialist having the tables turned on himself. The Nyungar people of what the State now calls the Avon Valley would not necessarily have thought in terms of "continents". This is not splitting hairs; this is recognising the limitations of using the colonising language to express the concerns and crises of the occupied.

The problem is in the application of a language of inquiry that is founded in the Western tradition, which allows Murray and others who "feel" displacement and seek to identify their loss with those of a people who have experienced extreme loss or have been placed under intense cultural and physical duress.

This is not to suggest a victim mentality, but to clarify obvious and subtle injustices. It becomes increasingly clear to me that non-indigenous people have no right to discuss indigenous issues - other than facing up to their own complicity in offence - without approval and permission, or invitation from indigenous people/s. |

[Above] Dingo Fence #2, Coober Pedy, South Australia, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1999)

By association, I layer myself around these discourses of Murray and Shoemaker that I criticise: and it is something I must confront and absorb in terms of everything I write or say. There are many different forms of silence.

A language of dislocation becomes necessary. A belief in the unprovable, the non-scientific. I saw the stripes of the thylacine as the creature moved up through a dry riverbed, over an island of she-oaks, into a patch of paperbarks. I saw its prints, had them photographed. It is a language I need not translate. I recite to myself, as mantra, these lines of Foucault's from The Order of Things (New York, 1973):

Once the existence of language has been eliminated, all that remains is its function in representation: its nature and its virtues as discourse. For discourse is merely representation itself represented by verbal signs. But what, then, is the particularity of these signs, and this strange power that enables them, better than any others, to signalize representation, to analyse it, and to recombine it? What is the peculiar property possessed by language and not by any other system of signs? (81)

[Above Left] Rock Art #5, Ubirr Rock, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001) [Above Right] Rock Art #6, Ubirr Rock, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

Habitation

To test memory and certainty I went back six months later. A different season - water in the river. I stood and stared for ten minutes, maybe longer. Maybe hours passed. Intrusion. A farmer wandered up to me eventually and said, I've seen you here before. You're X's nephew, aren't you? Your mob has been here as long as mine. Over a hundred years. I own that place upriver. There are a lot of snakes around here, during the hot weather. What are you looking at? Nothing, I'm a poet, just looking. He tells me of how young trailbike riders have been tearing up the place. I belong to a river preservation group. I don't use spray near the banks. I count the birds. This was a regular camping spot for the Aborigines, he said. He sounded sad. He owned most of the land surrounding the river, though no longer the river itself. My property used to go to the middle of the river - an imaginary line. But the government reclaimed the water and the banks - and a lot of good they've done with it. They scraped it clean and killed it. It will never repair. I have Aborigines in to stook at haytime, he added, and left me to my staring. The thylacine didn't pass by again, even though it was dusk.

Possibilities

Nah, it would have been a mangy fox or a feral cat. Or maybe a dog. Could have been a dingo but there have been none around here for years - that'd be rare enough. Best forget it.

I probably wanted to see it: to have imagined it creatively. To dream it. The word hangs there, like ritual slaughter. I cannot dream. At night, when I sleep, the compilations of images that break through to be verbalised upon waking are restructured to suit my waking needs. The thylacine looked: furtive, scared, defiant, elusive, downtrodden, combative… indifferent? It did 'run' or lope, weighted into its tail, its back legs doing the work, and it did stop and glance back towards me, then lope again. Its eyes were deep and black. We cannot use black unproblematically here. 'We' cannot ... ? In Dark Side of The Dream (North Sydney, 1990), Bob Hodge and Vijay Mishra write:

The role of Aborigines in the construction of Australian social identity illustrates a different kind of tendency. NonAboriginal Australians' attitudes to Aboriginal people have been dominated from the beginning by a mixture of guilt and hypocrisy. With other instances of the characteristic Australian paranoia the majority are victims of double messages, but in relation to Aborigines this majority benefits from them. There are vested interests in not seeing through this set of double messages, in maintaining a rigorous policy of hebephrenia, which then serves to sustain hebephrenic strategies elsewhere in the culture. But this in fact is the greatest cost of White racism. To no small degree the chains of hebephrenia that still bind many Australians are held together by wilful refusal to acknowledge the injustices inflicted on Aboriginal people in the past and the present, and to recognise the legitimacy of their aspirations for the future. (218)

|

The assumption that indigenous peoples are locked into the time of 'contact', that their social and artistic and cultural languages would have remained constant if 'settlement'/invasion had not taken place, is as devastating as the racism of incursion. The identification of the thylacine by a community with ancestral connections of tens of thousands of years; the elucidation of residual memory, the reclamation of totemic identity, is a language outside the discourse.

The Nyungar elders of the Avon region should be informed of this sighting. |

[Above] Rock Art, Ubirr Rock, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

This is not to negate the independence of the thylacine, of the family group it must be part of (a mate, cubs ...?), but to provide it with potential support for survival, to reinforce its chances. I'd like to imagine there would be a totemic respect. To hand the information over to a wildlife ranger (a State-employed official) would make the thylacine vulnerable - it would depend on the individual conscience of the ranger vis-à-vis State practice, as opposed to the probable communal and collective concerns of the Nyungar community. Perhaps I'm imposing my own assumptions here, but this seems a vital consideration.

Maybe this sighting is only intervention from the perspective of one who laments the loss of the family farm, who might make parallels with the loss of spiritual materials. This is an attempt to translate a sighting I do not understand. The 'sighting' becomes the process, the signifier, and then supplants the thylacine as the sign itself. Is there ego-fulfilment and cultural necessity at work here? It is not to become part of a tea-towel super-model advertising campaign for Western Australia. In her article 'To What Extent is Contemporary Aboriginal Identity Political?' (Those Who Will Remain Will Always Remember, ed. Brewster, O'Neill, and Van Den Berg, Fremantle, 2001), Denise Groves illustrates how Aboriginal identity and presence become commodified. The conflation of object and person, the marginalisation of a person's humanity, are played out by the media:

Thus the obsession with the categorisation of indigenous peoples continues - the 'authenticity' of Aboriginality is now legally determined on the basis of the ability of indigenous people being able to 'prove' their spiritual connection to country. Yet no recognition or compensation exists for those indigenous peoples whose 'spiritual relationships' with ancestral lands were severed as a result of them being forcibly removed and relocated by the State. It is as if they have forgotten.

Such forgetfulness is what Brown terms 'refracted knowledge' (1987:61). That is, rather than having to address 'black' political issues, the colonisers surround themselves with 'comfortable and familiar' images of the colonised. For the colonisers, Aboriginality has become essentialised in a series of 'familiar' metaphors - postcards, teatowels, Aboriginal gnomes and, more recently, in television commercials, as 'ochred, spiritual, and playing the didgeridoo behind the heroic travels of a black land cruiser, (Dodson, 1994:3). As Brown so eloquently states, 'it is as if a camera has been pushed through a gap in the mission fence' (Brown, 1987:61). (137)

The thylacine would be subtextually associated with aspects of indigeneity and exploited in this way, in turn exploiting the indigenous people themselves. There's a template already waiting for it.

|

Come and see 'didgeridoos and the rediscovered thought-extinct thylacine ...'.

The folding of quote within quote in the Groves excerpt indicates the disconnection through the mediating English languages. Discourse takes over. The points of oppression, as indicated, become sequestered to the evolution of the language.

The thylacine symbolises a particular kind of loss; the metaphor extended, the attempted genocide of indigenous peoples becomes a trope. A comparison engenders diminution of the person. Comparison to the condition of the extinct animal, and the desire to address the wrongs perpetrated, being perpetrated against indigenous peoples, become tangled. The comparison cannot be made.

But the association of the Aborigine in both nineteenth and twentieth-century "settler/citizen" poetry and contemporary media, with animals of "the land", outside the laws of totemic relations between an individual and a particular animal, is commonplace. I have seen many advertisements in the British media linking the snake and goanna with the desert-dwelling indigenous elder. |

[Above] Dingo #7, Bruce's Dingo Farm, Castlemaine, Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1994)

The creation of media stereotypes like this does not respect any specific relationship that might exist, but creates (or maybe reinvents) a notion of Bush and Outback that potential tourists (explorers) find exciting, exotic, and comforting. It is the classic formulation of the Other.

The condition of speech, of translation into English, is to create connections between the disparate. Cause and reaction: the implication of making language in a place that is tormented by the lack of willingness to address an ongoing crime is disrespectful, indifferent at best. The thylacine is a memory that's fading, replaced by a notion of injustice. The language of loss compensates for the extent of the crime. It is a celebrated memory of loss. The potential of rediscovery invigorates and negates the extermination. Hope is provided, wrapped in a healthy scepticism - without the scepticism there'd be recognition of ongoing crime.

What is Australian English? Aborigines may make English as well, as may all Australia's migrant peoples, whenever they arrive, and whether or not English is their birth-tongue, or indeed even one they use! The language is growing and deconstructing itself. Maybe I mean the English of the State: the English that speaks to its "citizens", but also instructs them, formulates and regulates their views. This official language is replicated by quasi-official organisations. To create authority it separates itself from the diction of the people, from the colloquial. State-language is anti-poetic language, though bad poems are full of it. The language of racism is reinforced by it, often by subterfuge. There is more poetry and language in the apparently "inarticulate" than in the State-sanctioned direction. The "guttural" language is a language of poetry. Eliot said "the perfect words in the perfect order', without understanding decontextualisation.

Truth and Lies

Truth is, the thylacine is not extinct. My conviction has returned, increased over the course of writing this essay. The sighting is an image of clarity. There is no intentional decoration in the language I am using to express this, and I am saying exactly what I mean. The thylacine is not extinct. This is an idea and a cadence. What I must ask is, despite my intent, is English so corrupted, so much the tool of avarice and conquest, of the violation of the other's rights, that it is incapable of expressing a truth? Can I only speak this gutturally? Can I see it unspoken? Can I see it written in sand as an image I might recognise from an encyclopaedia, a book of zoology, of anthropology? The listing implicates.

Moving the ashes of our family from the farm when it was broken up and sold off in sections, my Auntie said, 'Now I know how the Aborigines felt when their land was "lost".' The same problems that Shoemaker points out in the Murray are evident here, but my Auntie did not bring to it the nation-asserting belligerence that Murray emphasises with his 'bullshit' statement. Hers was a desire to empathise, and to placate and contextualise her own pain and loss. Property was sold, a new house was bought, and the family remained intact. There are no comparisons. What's left is a vestigial language of loss. We might feel fear and pity for this small thylacine group (we can assume there must be others), but we can share its suffering and isolation. The traps, the poison, the diminishing habitat. Guilt manufactures the simulacrum interconnection between the thylacine's position and that of the dispossessed Nyungars. But this can go nowhere. It is only knowledge within language, and its spiritual implications are unknown by me, the "us" referred to. It is an experiment in transference that leaves my voice empty, my sighting hollow and irrelevant. Well-meaning intrusion (even), would remove the remaining freedoms lefts to the thylacine. I have seen nothingness, the death of language. I am, and was always, inarticulate. The language cannot speak.

There is at least a group of thylacines in the wheatbelt area of Western Australia, living in remnant bushland. I know the specific location and have evidence that would excite the scientist and entrepreneur. I will not share it with them. The Latin name for this animal is: Thylacinus cynocephalus. Within this exists the lie. I would also like to acknowledge the indigenous people of the region known as the Avon Valley as the custodial keepers of the land, and to indicate my respect for their cultures and traditions. I will share this knowledge with them, should they want it. I have no doubts at least some of the community, or various individuals, are already aware.

[Above] Dingo #8, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

Footnotes:

[i] Actually the first single-author volume of poetry published in the State of Western Australia. See Nicholas Hasluck and Fay Zwicky in Bruce Bennett, ed. The Literature of Western Australia, Perth, 1979, p150.

[ii] Frank, the white settler who has lost 'control' of 'his' land due to injury incurred by fighting a bushfire (at his 'home' property), has become emotionally and physically reliant on his friend Ralph's goodwill. Because of this injury, Frank cannot follow 'black Wallace', but subtextually it is possibly because he cannot read the Bush. 'Black Wallace' works with the white thief Max - both ex-employees of Frank's who have left his block after Frank sustained the injury and couldn't return to work it. Max and 'black Wallace' set off together for the recently-opened gold diggings, where Ralph and a recovering Frank also end up. Max and 'black Wallace' in turn attempt to rob their former 'masters' of their considerable takings, (good clean-living boys like Frank and Ralph do not lose their money to the vices of the goldfields). There is an interconnecting series of binaries here, with subsets that distil into Greek heroic codes of behaviour-hubris, pollution, and Fate - as well as Biblical temptation, evil, and retribution. These codes are fused together, as part of a language of conquest, ownership, and spiritual validation.

Clay's poem is complex in its construction of roles of authority and servitude, with the injured Frank (as hero, then shade of a hero wallowing in his own misery, then his resurrection through apparent humility, bravery, loyalty, and strength of character), taking a subservient role in order to be elevated again to his status of master:

And Ralph came here to ask if you could spare

Old Jonathan, to mind the tent for him;

But now he is to wait for me, and I

Will wash the gold and guard the tent; and he

Shall be to me as David,-for myself

Will be his Jonathan. (56)

The pairing of the 'demonic' Aborigine and the corrupted white Max is an attempt to assert the polluting nature of 'blackness'. Though Max actually injures Frank in his efforts to steal the gold, Max is simply described as cowardly. 'Black Wallace' can only ever be a demon, a demi-figure against which the hero competes or is corrupted. Max is of the chosen, though corrupted and fallen. He is literate, thus 'civilized', despite having been corrupted:

'Now hark ye,' says the doctor, as he marks

A tinge of color to the cheek returning,

And the breath coming freely;- when that hand

Can dash off an epistle, stroke and dot

As true as ever,-you can write a note

To that big, cowardly Max, and thank him for

The ugly shock that gave you back an arm

Himself may feel the weight of, any time

He ventures to your presence!"(72)

A recognition of the duality and duplicity of such representation is actually figured in a set of gender binaries posited in this long poem. The recognition of settler crimes and injustices (where 'settler' is the generic 'white') is presented by Ralph's mother when he and Frank find bush blocks away from their family holdings, and wish to venture out to develop them. It's another inversion, with the stage for her recognition being set by fear and distaste:

'Dear, brave boy!'

The mother says, and strokes his curls

With loving pride;- 'This seventy miles away

You youngsters count as nothing; but I wish

'Twere not so far. Those inland savages

Know little of the whiteman, and I fear

They will be troublesome.'(11)

We then get a riposte from the father:

'Nay, fret him not,'

The father says: the boys will never know

The roughing of their fathers; when the men

Were always armed, and muskets cleared the way

While Women journeyed.' (11)

And the rejoinder from the mother:

'Ah!' the mother said,-

And a dark shadow o'er her visage fell,-

'There are wild stories sealed upon the lips

Of some who landed first, should make men blush,

And women tremble: tales of cruel scenes

Where whitemen played the traitor, and surpassed,

In subtle guile, the dark man's treachery;

When hunters forayed-not for fox or hare,

Or rebounding roebuck,-but for men,-aye man

Made in GOD'S image; tho' they saw it not,

Who sought and trafficked for a black man's head

As Saxon Edgar sought the heads of wolves.

'So eager horsemen and lighthearted girls

Dash among timorous groups of kangaroo,

With dogs and rifles,-pleading poor excuse

For needless slaughter,-till the pitiful Night

Over her blushing face spreads her pale hands,

And moves them to forbear; the plain all strewn

With carcasses that taint the wilderness;

None feeding save the wild dog's howling pack,

Or the grim laughter of the carrion crow.'(11)

This astonishingly explicit and terrifying account is immediately rejected by the father, as authority and master, by a revisionism with familiar echoes. The use of 'metaphor' implodes the language, undoing the accusation by the 'truth' of the poetic as the most intense and purified form of language usage. It is a specific deployment by the poet of poetic validation. The idea of the metaphor exploding is beyond the fabric of the poem - that is, the risk of failure to contain must be prevented. This is what form does in the poem of unified self, of linearity.

'Mother, you paint one side,' the old man said;

'Your metaphor explodes, for you rammed

Both charges in one barrel. Sure you know

When spears are whistling round, and blood is hot,

It flows the sooner; and 'twere sorry task

To parley sentiment with savages

Who gladly would have swept us to the sea.'(13)

This is the language of propaganda, and the language of war. It is also characteristically highly sexualised, and the penetration symbolism of gun barrel and spear is mixed and overlaid. The barrel being double-loaded is as threatening as the spears - the suppression of the female becomes framed in the same light as the suppression of the 'savage'. Throughout the poem there's a sexual tension wrapped up in images of injury and healing: between Ralph, Frank, and their respective sisters Elsie and Ruth - each male loving his friend's sister, and vice versa. There's also the homoerotic bonding between the males, the sexualisation of the demonic Other, and the struggle we have seen over truth and representation between Ralph's mother and father. The driving inwards, the movement away from the coastal edge and the fear of the heart of the land, the typical 'dark heart' is emphasized in the flows and sweeps of blood and water, the assimilation of passion and retribution.

Ed's Note: A commercial permit for the photography and artwork relating to indigenous culture used in this article and on the Thylazine website has been obtained with grateful acknowledgments to Environment Australia and the aboriginal traditional land custodians of Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia.

About the Writer John Kinsella

|

John Kinsella is the author of more than twenty books whose many prizes and awards include a Young Australian Creative Fellowship from the former PM of Australia, Paul Keating, and senior Fellowships from the Literature Board of The Australia Council. He is the editor of the international literary journal Salt. He was appointed the Richard L Thomas Professor of Creative Writing at Kenyon College in the United States for 2001, and where he is now Professor of English. He is a Fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge University, and Adjunct Professor to Edith Cowan University, Western Australia. His selected poems and selected essays are forthcoming, as well as a new novel Post-Colonial and a book of short stories (co-authored with Tracy Ryan). John Kinsella is now the poetry critic for the Observer newspaper (London). |

[Above] Photo of John Kinsella by Wendy Kinsella, 2001.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.3 (March, 2001) |