MY ARTHRITIC HEART

writing an illness narrative that refuses to be 'inspiring'

By Liz Hall-Downs

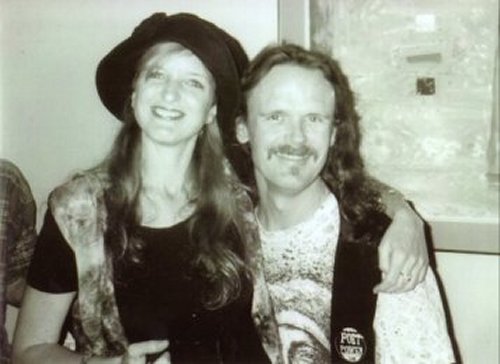

[Above] Liz Hall (now Hall-Downs) bushwalking at Barramunga, Otway Ranges. (Photo by S. Curtis, 1987)

Part One: The 'Why' of the Writing

My plan was to become a writer. But then the unexpected happened. At the age of twenty, during the first year of a degree in professional writing, I was diagnosed with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). Having worked previously in the nursing field, I was all too aware of what this diagnosis meant for my future and was absolutely devastated. I dropped out of university six weeks before the end of the year. I still wanted to write, but the disease was raging through my body and my hands were so inflamed and swollen that I often couldn't use them to perform the most basic functions, such as dressing myself, turning keys or taps, opening jars and doors, hanging the washing, or preparing a meal. Driving became very difficult, as did walking, and severe and unrelenting pain was my constant companion.

My writing became increasingly important to me. It was no longer just something I used as an escape valve for my less palatable emotions; it seemed like the only thing I could still do, and it became a lifeline to the outside world. I was no longer a nurse or student. Socially, I had become a pariah - in a culture where people are defined by their careers and ability to earn an income, I had no career and no prospect of getting one. My prospects of living a normal life like I saw others around me doing had ended. To make matters worse, people would say incredibly rude things to me - when they weren't disbelieving of my situation because I 'looked all right to them', they were offering me diet and exercise advice which, if I didn't agree to, proved I 'didn't want to be well'. Or they trivialised the systemic nature of my disease by telling me about their grandmother's bodgy hip or their tennis elbow or their football-damaged knee and insisting that they knew what I was going through.

Rheumatoid Arthritis is the most chronic and disabling form of arthritis. It is a systemic, incurable condition that affects about 1% of the population. It affects women in 75% of cases, and its peak onset is between the ages of 20 and 45, though it also affects children, and sometimes even babies. Clearly, RA bears little resemblance to the community stereotype of arthritis as an 'old person's disease'. Being an auto immune disease, RA is in fact more closely related to conditions such as Multiple Sclerosis (MS), except that instead of the body's white blood cells attacking the myelin sheaths surrounding the nerves, in RA they attack not only the joints, but also the skin, heart, lungs, spleen, muscles, throat, bones and nervous system.

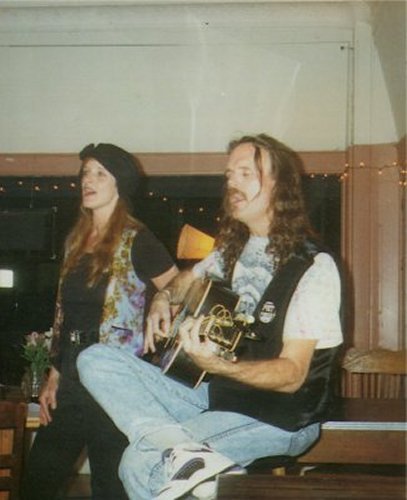

[Above] Liz Hall-Downs and Patrick at home, Greenbank, Queensland. (Photos by Kim Downs, 2006)

RA is characterised by systemic inflammation of the whole body, resulting in low-grade fevers, night sweats, anaemia, severe fatigue and, obviously, depression. It is characterised by acute 'flare-ups' of the condition, and inexplicable periods of remission. You can pick an RA sufferer by observing their hands and feet. Unlike Osteoarthritis, RA usually first attacks the small joints of the hands and feet, usually in a symmetrical fashion, causing pain, inflammation, redness and heat, and eventually resulting in total destruction of the joints cartilage and and permanent structural deformity. Only in Stage 2 does RA generally move to the larger joints such as the knees, hips, back and neck. Without diagnosis and treatment, RA can shorten a sufferer's life by an average of 15 years but it is not considered a terminal disease. Though it is certainly terminal to quality of life.

The pain of RA has been described as throbbing or knifing, and, when the disease is flaring, requires strong pain medication to keep it under control at all. Even when in remission, RA sufferers still experience mechanical pain in the joints that have already been damaged by the disease process. Access to adequate pain relief can be a real issue, especially for young people with this disease. Some doctors are reluctant to prescribe codeine, because it is classed as a narcotic and considered addictive, but it is the only pain medication that has worked for me. If the pain is not dealt with, patients will resort to anything that works for them and begin self-medicating - with alcohol, street drugs, anything they can lay their hands on. It's hard for people who have never experienced this type of severe pain, day after day, to appreciate what it is like and how it can literally tip a person over into a kind of madness.

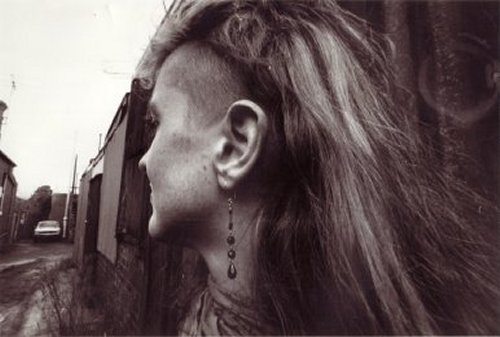

[Above] Liz Hall (now Hall-Downs), Collingwood, Melbourne. (Photo by S. Curtis, 1987)

With the worsening of my condition, the power relationship between the world and myself changed. I was no longer a young, educated person with a bright future ahead of me: I was, oftentimes, a helpless invalid that people felt superior to. For some years I used a walking stick, as the joints in one of my feet had deteriorated so badly that I needed assistance to walk. This made my condition even more visible and, although I had initially felt frustrated by people's insistence that I 'looked alright to them' and must therefore be 'putting it on', using an obvious invalid aid was even worse as they identified me as 'disabled'. To many people this word seems to be synonymous with 'stupid' or 'mentally defective', and people often had no qualms about baldly demanding that I explain myself to them. ('What's wrong with your leg?') Though this might initially seem to be an expression of concern, try hearing it from total strangers every time you leave the house! I daresay these same people wouldn't confront someone in a wheelchair and demand to know how they broke their neck!

But I could still write. So I gathered up my poems and took myself down to the local poetry cafe. I remember clearly the very first time I stepped up to the microphone. It was mid to late 1983, I was twenty-two years old and terrified. It's the only time, before or since, that I've physically experienced the phenomenon of my 'knees turning to jelly', but regardless I haltingly made it through three or four poems and was stunned by the enthusiastic applause that is reserved for 'virgin' poets. I became a regular reader at the cafe, and found a friendly group of peers who saw me as someone with promise who could write a passable poem, instead of a malingerer or a disability on legs. I can't overstress how important this was to me at that time.

For the next decade, I frequented readings and writers' festivals and put a lot of effort into getting my work published, publishing over 100 poems in literary journals and magazines and doing a lot of performance, both solo and in collaboration with various musicians and other poets. In late 1991 I managed to finish the degree I had started ten years earlier, then moved to northern New South Wales, where I met my partner, Kim, a writer, sculptor and musician. I had had a few years of remission in the late 1980s - early 1990s, but then the disease returned with a vengeance. With my health deteriorating rapidly, I was finding it increasingly more difficult to get around. I was bedridden, despairing, depressed, in constant pain and overwhelmed with a sense of hopelessness. Kim officially became my 'carer'. For the next few years we collaborated and performed together as 'Fit of Passion', but this was something I would have been physically unable to do alone. We moved to Brisbane in the mid-90s.

|

Over time, 'Fit of Passion' developed into a complete poetry and music show. A hybrid of serious poetry, rhythmic and sometimes comedic observation, and original music with vocal harmonies, the material dealt mainly with issues of gender, from both a male and a female perspective.

I started to really enjoy performing again, because I was working with someone who wanted to work with me, not against me, and, as neither of us were stupid enough to believe that literary fame and fortune was just around the corner. We refused to bother with all the silly ego stuff we'd encountered almost everywhere, running like a seam of evil bile through poetic communities. In 1997 we received a touring grant from Arts Queensland to take the work around regional Queensland, and spent much of 1997-1998 on the road. As part of the grant, we published and recorded the work and sold over 400 books and 250 tapes over this period (not a bad figure, given that the average print run for poetry with mainstream publishers in Australia is only 500 books). |

[Above] 'Fit of Passion' in performance, Liz Hall (now Hall-Downs) & Kim Downs, Columbus, Ohio. (Photo by photographer unknown, 1994)

But it was frustrating having to self-publish yet again, particularly as people had been asking me for years where they could buy copies of the performance poems I was presenting. Pushing myself like this ultimately left me in even worse physical shape and, by the end of 1998, I was taking a very nasty cocktail of prescription medicines - cytotoxics, steroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and codeine - just to get up in the morning. I did only occasional readings, though we still sometimes trotted out the 'Fit of Passion' show when there was paid work in the offing. I hoped I'd perform again in the future, but assumed it would never again be on such a scale. Frankly, the price, both physically and psychologically, was just too high for the minimal returns, and if it wasn't fun I wasn't interested. And the longer I stayed away from performing, the more I felt like writing poetry and fiction again.

As part of my Master's Degree in Creative Writing at the University of Queensland, I began work on a manuscript of poems called My Arthritic Heart. I describe the collection as an 'illness narrative' and, during its writing, I found myself experiencing a kind of emotional catharsis, a sense of freedom, as if my psyche had been long bound with tight cords that held in all those unsayable things that are associated with chronic illness - unsayable because of social censure, fear of exclusion, and unwanted pity. (People like to think they are kind and understanding, but ask any person with a long-term disability how this translates into avoidance, fear, and even worries of contagion. There is a lot of social pressure on people with disabilities to be 'grateful', to be 'nice', and to present a cheerful facade to make others feel more comfortable. This is one of the reasons so many people with chronic illness withdraw from society - a classic case of 'Laugh and the world laughs with you; cry and you cry alone'.) By beginning work on a poetry volume that dealt specifically with these issues, I felt I was beginning to free myself. In hindsight, it's amazing to me that I had spent almost twenty years writing, performing and publishing poetry, but had been unable to put out into the public arena any expression of the very real suffering I was experiencing health wise throughout those years.

Of course, I was in a different (and some would say privileged) position, having lived on the margins of what's considered 'normal' society (mortgage, job, three children) for so long; I'd had the luxury of time (these days a scarce and much sought-after commodity) to spend reading and writing, and thinking about reading and writing.

|

But as should be clear from the details I've shared about my life up till now, it certainly wasn't easy and I'd have much prefer to have had economic security and my health. I came to the realisation that this really was the poetry that I'd been building up to for the past eighteen years, the poetry I was 'born to write', and that the discrimination and ignorance (and sometimes outright cruelty) I'd encountered for so long were also being experienced by many, many other people with disabilities and illnesses who were not writers. So it fell to me to try to put this experience into words that can help others to enter into, and hopefully gain understanding of, the situation.

It's hard to feel understood, or to gain emotional or moral support, when other people are totally ignorant as to what exactly they are dealing with, while at the same time feeling superior to the sufferer simply because they perceive themselves as 'well'. I've attempted to deal with this perception, and the often cruel and heartless judgments of others, in My Arthritic Heart. The poems are, at times, strident in tone, but I make no apology for this - the book also has its share of sadness and, I hope, joy. Anyway, there's no rule that says poetry has to make the reader feel good, and if my goal here is to communicate the truth, then anger is very much a part of the equation. |

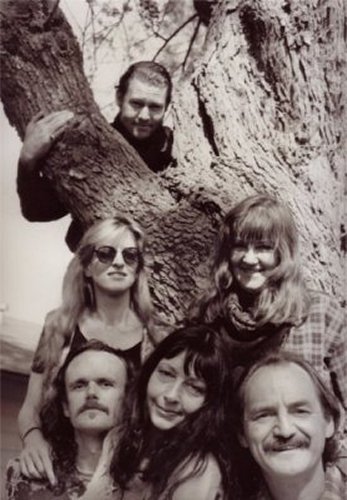

[Above] 'Ozpoets' troupe PR photo, clockwise from bottom left: Kim Downs, Liz Hall (now Hall-Downs), Grant Alexander McCracken, Pamela 'Mimi' Sidney, Denis Woodley, Alex Mellor (now Krysinski), Austin, Texas. (Photo by Herman Nelson, 1994)

Still, doubt always creeps in. So I asked myself: is the decision to write autobiographically about illness simply self-indulgent? And I answered myself: by necessity. Here's my rationale. For twenty years I had been second-guessed, misunderstood and counseled (whether I want it or not) by people who had no clue about my illness, its aetiology or its effects. It took me a long time to work up the courage to write about my illness, and I felt that direct reference to my personal situation was the only possible route to take. It could well be that the resultant book is 'bad', in literary terms, but at least it tells the truth as I see it. Besides, in my poetry I have always concerned myself with perceived injustices, whether the inequality of women, the marginalisation of the poor, or the madness of environmental destruction and war. So perhaps it was time I tackled the injustice in my own life a little more forcefully.

What I'm striving for with this work is an overall effect, borne from my desire to create a text that describes a little-understood and widespread illness in the hope of engendering community awareness. Whether the poetry is 'good' or not I'll leave to others to judge. But I don't subscribe to the idea that such personal work can automatically be dismissed as 'poetry as therapy'. Rather, I believe that all creative writing is personal to the extent that it is necessarily informed by the writer's life experiences and emotions, even if these are veiled by character and story. It is the writer's personal obsessions that make him or her choose their subject matter in the first place. I have, however, sought to approach the work honestly, to let go (at least in the initial writing stage) of the nagging voice that says, 'For God's sake, don't say that!' I've attempted to look at the world through the filter of illness, which adds its own strange colours of pain, distance, and alienation that completely alters one's vision/view of the world.

|

I reminded myself when writing that my subject here is not just my own illness experience, but mortality itself. We all experience sickness and death, but I do think that chronic, incurable illness at a young age also creates a whole new set of issues to do with people's expectations about youth. Socially, this creates a terrible sense of difference from one's healthy peers, which I hope the poetry in some way addresses. I wanted to present not the strictly chronological but the emotional facts, that is, the feelings that accompany the experience of chronic illness. I wrote the poems to try and transcend the feeling of being an 'alien', or 'symbol' representing a disease state. I wrote the poems to express the frustration of being limited by my illness. I wrote the poems to reclaim myself from a physical condition that threatens to define who I am. And I wrote them for the many, many other people who are in a similar situation. |

[Above] 'My Arthritic Heart', published by PostPressed, Teneriffe, Brisbane, Queensland, 2006. (Cover Art by Robert Maxwell and Cover Design by Jeffrey Harpeng, 2006)

Maria Troy and Tom Owen, in a paper discussing sado-masochistic performance artist Bob Flanagan's show 'Visiting Hours' and HIV performance artist Ron Athey's work, wrote that these types of works:

"point to how disease is consumed in our culture, how images of the 'sick' form a focus point for the fascination of the 'healthy.' This point knits together contradictory impulses. Looking at the dying, we feel emotions of pity, empathy, sympathy; we recognize ourselves as animal, as germ-plasm. At the same moment, we pleasantly discover that we are not sick! Fate has not yet touched us. We can stand aside like the white-linen colonialist in the village of brown and starving children; this is not our world. And no desire to shock and instruct, or make the audience see things from the diseased person's [point of view] can compensate for the fact that misery isn't dished out evenly throughout the social body."

Byron Bay poet Jen Jacobs made this feisty point about the ill person's 'otherness' (with the added emphasis on non-visible disability):

"I look like I live in your world

I can pass as a well person - for a short time,

I'm good at pretending

... I no longer have automatic residence

in your country,

my citizenship is of another world entirely;

where pain is usual,

time and distance treat us differently, and

'how are you?' and

'what's wrong with you?' and

'are you better yet?'

are

very

rude

questions."

Troy and Owen pointed out that:

"Athey's work makes people uncomfortable ... Perhaps the naked presentation of disease seems more likely to 'transform society' by freeing it from the misery of false appearances, from representational ploys and other sublimations. ... [The] work walks the line of desire/repulsion and, typically, invokes the strong reactions that tampering with a societal taboo raises."

Under the heading 'The Institution is Sick', they wrote:

"To be diagnosed with a disease or condition means to be evaluated, processed, and entered into a specific relationship with medical, social, and economic institutions. Difference has become measured, biological, and ascertainable if not predictable. Diagnosis clarifies institutional and social relationships by abbreviating the elaborate, whole-body experience of disease into terse, exchangeable medical terms. Flanagan's years of struggling with CF [Cystic Fibrosis], his ways of coping and surviving can not be found in a textbook on CF. In Visiting Hours he takes the display of his body away from medical institutions and arranges it himself."

and

"For Flanagan, 'fighting sickness with sickness' [is] the way he has been able to survive. He is the victim/torturer, usurping the power of his Cystic Fibrosis and the medical experts over his body."

Troy and Owen remarked that this 'victim' stance 'is really no different from the 'marginal' position 'reserved for artists, the special spot from which artists speak', but that the issue this type of art raises for critics is that it 'has challenged the ability of criticism to speak, challenged what criticism attempts to establish as a right community of taste'.

As to this question of 'taste', who are critics anyway to dictate whether we can represent the realities of our lives and illnesses in our work? If it's 'uncomfortable' for others, imagine how uncomfortable it is for the ill person to be continually marginalised and expected to be 'nice', not 'complain' and accept other people's pity?

[Above] Liz Hall (now Hall-Downs) in performance with comedy duo 'Dog Breath' at the launch of 'Writers of the Storm: 5 East Coast Poets', Catalinas, Byron Bay. (Photo by Graham Batterbury, 1993)

Here's another, salient quotation on the tackling of unpalatable subjects in poetry:

"[Rockhampton poet Mark] Svendsen counters suggestions his symphony poems dwell too much on death and negativity with his conviction that only by facing what makes us hate will we learn why it is right to love. ... 'Poetry ... sounds the resonances of the great emotions, or the archetypal emotions of the human race. …[It] is indispensable.'" (Kelly)

I have always believed that the purpose of writing creatively in the first place is to communicate. And, in the case of My Arthritic Heart, I'm aware that my audience is not only (as is often the case with poetry) other poets and writers, but also other people who suffer from RA and other auto-immune diseases and their friends and carers, as well as the general community. I am not naive enough to assume that the lack of understanding and downright discrimination I have experienced for my entire adult life is peculiar to me, but suspect that in writing this work I give voice to the frustrations that many people in my situation routinely feel.

Approaching the writing itself is not easy, and deciding whether the poems are 'good' or not is even harder, requiring a level of objectivity that is difficult to find when contemplating one's own work. As Stevie Smith said, when a friend praised her poetry:

"I am never very certain about them, the inspiration or whatever it is comes in such a vague and muddled way, and I am not sure that I don't sometimes get the wrong poems into print." (Barbera 135)

It's important to realise that everything I've written here is haunted by the spectre of illness, daily low-level pain, and periodic flare-ups (with severe, unrelenting pain) that are the hallmarks of Rheumatoid Arthritis. The struggle of living with illness has made me far more sensitive to the sorts of ego politics that seem to go on in all groups of creative people, and I simply refuse to put up with this sort of thing, because the stress of it ultimately makes me sicker. Having a supportive partner, after all those years of desperately trying to define my worth (and indeed my existence) by writing in defiance of an illness that has for so long prevented me from participating in mainstream society, has made all the difference. Instead of being a lifeline, a means of survival in desperate times, writing has become simply an adjunct to an increasingly satisfying, connected life. Where poetry was once all I had, now it's just something I do (along with gardening, cooking, bird watching, and other things that give me pleasure), and I'm back to where I started before I came down with my illness - working from a more secure base and aspiring to complete larger works such as novels. But the illness still remains - relentless, worsening, exhausting and soul-destroying.

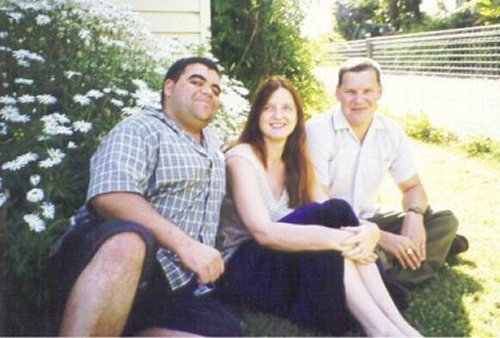

[Above] Poets from the 'Blackfellas Whitefellas Wetlands' project, for Brisbane City Council and Boondall Wetlands Management Committee, from left: Samuel Wagan Watson, Liz Hall-Downs, B.R.Dionysius. (Photo by Kim Downs, 2000)

This is where being an ill or disabled writer in the public arena becomes nigh on impossible. Writing good work is a challenge, and getting it published an even greater one. But if the writer is unable to travel the publicity trail required to achieve sales in these times (which are, undeniably, difficult for the entire writing and publishing industry), he or she is very likely to be overlooked in favour of someone who can meet these demands. Recently, Shirley Conran, the author of the bestselling Superwoman has come out publicly about her debilitating ME (myalgic encephalomyelitis) and CFS (chronic fatigue syndrome), admitting that for years she hid the fact of her illness because to not do so would have been career-destroying. "Being ill is very bad for business ... You'd never get that seven-figure contract if a publisher knew you were ill. The only prudent thing to do was to keep it a secret." (Grice)

But secrets cannot be kept forever. At some point one wants to be known and understood, and this is something I desire far more than success as a writer. Perhaps all I have achieved in writing My Arthritic Heart is to clarify for myself my experience and my position on illness in society. Or it could be that the reading public is slowly becoming ready to hear the less palatable aspects of the illness experience.

This is borne out in correspondence from one of my writer friends ('Sue') who suffers from severe ME/CFS. A few years ago, she entered a competition for writing which dealt with 'overcoming adversity'. She sent me the guidelines, and remarked that no-one wants to hear the truth of our misery, only the 'inspirational' stories of how such difficulties are overcome. Despite being one step short of suicidal, she wrote a piece to the guidelines and was highly amused when it won first prize with a promise of publication in a book of winning and short-listed entries. A year later, she wrote me the following remarks:

"That book I won first prize in, (and still haven't seen the cheque), has been remaindered by the publisher. Apparently a book about sick and traumatised people meeting the challenge in a brave and heroic way just didn't sell. Who'd have thought? (I still want my cheque, which he reckons he posted - yeah, sure.) The poetry group I'm in is doing an anthology. They want mainly my poems about illness. Not sure if I'm comfortable being the 'sick person' poet, or having my pain used 'to balance the book', especially when they've only asked me to submit at the last minute."

When I wrote back I remarked that at least they'd asked her to submit. For writers who rarely appear in public, there's some heart to be taken from the realisation that at least we are not completely invisible yet. But mainstream success? Not very likely. So we continue to write for ourselves, and for others like us. Our self-expression is all we have.

Part Two: After The Writing - What Now?

My Arthritic Heart was originally part of a Master of Arts (Creative Writing) thesis undertaken at the University of Queensland, and spent some years in the proverbial bottom drawer. During the process of editing the text for publication I discovered that it's one thing to publish such challenging work within academia, but quite another to release it into the public arena, and the publication of this poetry has, at times, filled me with trepidation.

My many ill and disabled friends have, however, convinced me that its publication is worthwhile. Unlike most of the writing about illness that makes it into print, my work does not attempt to be 'brave', 'courageous' or 'inspirational'. It is not about 'overcoming adversity' but about how one lives with adversity in an uncaring society. It does not say: 'look where I've been and how strong I am to have overcome it'; instead, it says: 'ill people are all around us and society refuses to see their suffering, unless they present to us as 'inspirational'. What a burden the latter is to carry, and how superficial! Certainly most people who have experienced life-changing health problems are eventually able to list the ways in which it has changed them for the better, but to demand that they present this 'feel good' view of their lives and gloss over the messy details of living through serious illness and its treatment, just because it might make others feel queasy or remind them of their own mortality, is essentially refusing to see the whole person. But why should this be so? Why should triumph over pain and suffering be applauded, while the despair and hopelessness caused by this same pain and suffering is deemed unacceptable to express? Are we whole people or compartments of 'acceptable' and 'unacceptable' qualities?

I have lived a dual existence since my diagnosis twenty-five years ago. My persona as a poet and writer and my other identity as a person with a disability, forced to live on society's margins, have existed independently. This was partly a conscious decision as I had so often observed the unequal power relationships that the disabled are forced to endure from the patronising able-bodied.

|

In my quest to be taken seriously as a writer, I felt I didn't need the added burden of having to prove that my work had value in spite of my physical situation. To me, my work has value because I have worked on achieving a standard of excellence. Ultimately the poem on the page is all that matters, and not the personal situation of the poet. So, to my current personal situation. |

[Above] PR photo for 'Fit of Passion' project, Liz Hall-Downs and Kim Downs, 1997. Photo taken in Columbus, Ohio, USA. (Photo by photographer unknown, 1994)

After several years of being almost bedridden much of the time, I'm happy to report that, with government-funded access to new treatments that have recently become available, I have been able to regain much physical function I had thought was lost to me forever. How long this situation will last, how long these drugs will continue to mask my illness, is unknowable. So there is only today, and what I can achieve today. And I choose to find the joy and meaning in each today, as this is where I believe 'happiness' resides. But who I am is inextricably tied to the things I have experienced, and that trusting young girl who believed in humanity's essential 'goodness' is long gone and will never return.

I have always known that the natural world is the best place to go searching for healing. In my twenties I made numerous attempts to find my 'place in the bush' where I could nurture my creativity, avoid the stress of city life that exacerbates my illness, and live in harmony with nature's cycles. Victoria's Otway Ranges was a significant place of healing for me in the past; the northern New South Wales 'rainbow region' has also been significant. Nowadays I live in South East Queensland on a bush block, surrounded by trees and wildlife. I have been fortunate to find a partner who supports my efforts towards wellness while still making allowances for my physical limitations. Together we play 'old time' music - I'm gradually becoming a proficient bush bass player, and the harmony singing brings great pleasure. We enjoy the company of a host of parrots (two galahs, two cockatiels and a rainbow lorikeet) and they bring daily joy, amusement, love and companionship.

Sometimes I venture back into the poetry scene, but I no longer expect to find many friends there. I recognise that within groupings of creative people often exists a competitive and destructive narcissism, that is just too close to the narcissistic personality disorder that tainted my family of origin for me to ever feel comfortable around it. I've co-published six collections and performed all over Australia since the early 1980s, and toured the USA in the 90s. I've weathered the academic snobbery of highbrow 'readings' and had beer cans thrown at me at lowbrow ones. It's true to say that to be an 'out there' poet in this country equals being able to do it all - reciting, acting, singing, strutting, recording, publishing, gaining academic qualifications - and I have done it all. I have also recently had young performance poets negatively review my work on the basis that they think I'm an academic who only writes for the page and is somehow part of some hated 'establishment', and I have had academic poets negatively review my work because they think I'm a lowly 'performance poet' who writes in a form they abhor. All I can say is you can never please most of the people any of the time. Which is why nowadays I just please myself.

|

Needless to say, My Arthritic Heart is not geared towards this type of audience, who seek not to understand the work, but to vilify it, labouring under the false notion that bringing others down elevates their own position. Instead, I would rather put the work out amongst the arthritis and disability communities, where it might actually help someone else to see this common experience - of trying to live in a ruthless and money-hungry society while battling illness - put into words. |

[Above] 'Cathouse Creek' - alt-country, roots & blues trio, from left: Kim Downs, Liz Hall-Downs, Gary Nunn. (Photo by Dave Granato, 2007)

I have many friends with disabilities who do indeed inspire me, not with the strength of their 'overcoming' but with the stoicism of their endurance and their ability to find joy and laughter in lives that could so easily - and understandably - succumb to depression and despair. Every day I look out my bedroom window at the resident family of wallabies and marvel at their quiet enjoyment of the basics - sunshine, space to roam unmolested by traffic and domestic animals, fresh green shoots to eat after rain. They do not know that their habitat is increasingly growing smaller, that their numbers are quickly dwindling as more than one thousand people move into this fast-developing region. And if they did know, what good would it do them? They are happy to be here now, serene and at peace with their surroundings. And, likewise, so am I.

References:

Barbera, Jack and William McBrien. Stevie: A Biography of Stevie Smith. London, Heinemann, 1985

Grice, Elizabeth. "I was 40, but felt 70" (interview with Shirley Conran), The Courier-Mail. "Life" section, 29/3/03, p.6

Jacobs, Jen. "From Behind the Fog Curtain." Illness: A Journal of Personal Experience. 1.1 2001:100-101

Kelly, Patricia. "Up At the End." Courier-Mail. 19 May 2001: BAM: 4

Troy, Maria and Tom Owen. "Artists, Disease and Marginality", P-Form. 36 www.pform.org/archive/36.html Downloaded 21/8/01

Several paragraphs of Part One appeared in the thesis "My Arthritic Heart and Making a Writer", University of Queensland, 2002. My Arthritic Heart is available from Post Pressed in Queensland.

About the Writer Liz Hall-Downs

|

Liz has been reading and performing poetry on stage, on TV and radio in Australia and the USA, and publishing in journals, since 1983. Liz also writes fiction and essays and works variously as a community artist, writer-in-residence, editor, singer, proof reader, and manuscript assessor of poetry, fiction and non-fiction. She holds a Bachelor of Arts degree from Deakin University (VIC) with major studies in Professional Writing & Literature and a Master of Arts in Creative Writing from the University of QLD. Her most recent collection is My Arthritic Heart (PostPressed, 2006). Previous collections include, Girl with Green Hair (Papyrus, 2000), Writers of the Storm: 5 East Coast Poets (Tyagarah consultants, Lismore, 1993), and Conscious Razing: Combustible Poems (1986). She is currently working on a realist novel, The Death of Jimi Hendrix, and singing and playing bush bass with the trio 'Cathouse Creek'. |

[Above] Photo of Liz Hall-Downs and Alice by Kim Downs, 2001.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.12 (June, 2007) |