DISAPPEARING LANDSCAPES

By Warrick Wynne

[Above] Suburbia on the Move. (Photo by Warrick Wynne, 2004)

Around here things are being reshaped. The old patterns, lines and ridges are being subsumed and the yellow paddocks that waved in the wind and reflected the long shadows of the clouds are being punched through with roads and house blocks and exotically-named subdivisions with no relationship with the past or what was real. This is the edge of the suburbs, on the Mornington Peninsula, about fifty kilometres south of Melbourne. From here I could look across the ridges and the rolling farmland that falls down to Harrap Creek, up to the next ridge where the old farmhouse still stands in its grove of dark green pine trees and imagine the next fall down to Balcombe Creek, which flows into Port Phillip Bay near Mount Martha.

You could imagine the fall and flow of the land, the topography, the sense of rise and fall because you could see the shape of the land. Now the houses are coming. The signage and estates are on the move with their billboards and their temporary looking site office and their brick entrances which are intended to speak of permanence but speak more in appearances and clichés. They build brick entrances to the estates like entries to medieval towns, giving them exotic names and inscribing them in the bricks and stone: 'Cresta Views', 'Balcombe Crest', 'Canterbury Park'. These are designed to give the place a sense of belonging, even history.

[Above] Names and Walls (Photos by Warrick Wynne, 1999)

But behind the brick and sandstone facades, the newly created coats of arms and the stone engravings are fields of dandelions, or the first scrapings of the land for the new shapes of the roads. This place is changing. Mornington East is the fastest growing residential area on the Mornington Peninsula, with an annual growth rate of 11% and the eventual construction of around 5300 households proposed in the Mornington Peninsula Shire's document 'Planning for Growth'. At the edge of town the farmland is becoming suburb and the fields are becoming subdivisions with avenues, crescents, drives and courts being overlaid with their new shapes over the old lines.

It is this re-shaping that seems worst to me somehow. That these new lines and grids are superimposed on the old lines of the land without any meshing of the two worlds. The belief that this landscape is worth so little that nothing of it need be preserved or even remembered. When I asked at the Council about what their long-term planning ideas were, besides the zoning of certain areas as residential, low density residential etc. they told me that they had no plan; 'We just wait for the applications to come in and look at them then', I was told. There's certainly no apparent attempt to retain any old lines of the past in the shapes or even the names of the new suburbs that are being created. Everything has to be scrubbed clean, washed of its original shapes, re-named and re-possessed. In a way I've seen it all before.

I grew up in the northern suburbs of Melbourne in the early 1960s when Melbourne was already spiraling outward just like my Year 9 Geography books said all cities would. In those days you bought a house at the newest edge of the suburbs and built; just a little further out than your parents maybe. I don't remember they had names beyond the names of the railway stations they seemed to cluster around: Strathmore, Oak Park, Glenroy, Broadmeadows and the unknown beyond.

As kids we would roam the borderland between the subdivisions, the new house blocks, the hastily assembled shelters, and the actual farm land. It was a parched prickly landscape of fields laced with tracks beaten out by paddock bombs, a landscape of thistles and stones and danger, bisected by the natural delineation of the Moonee Ponds Creek and the unnatural boundary of the train line north, and the forbidden Trestle Bridge.

|

Landscape

Mine is the half folds

ahead of suburbs,

the wreckage of posts and palings

already fading.

Mine is the barbed wire buried

and the fence wires of paddocks

unearthed in new backyards

where thin sheep were.

It is the husks of cars

stolen and abandoned

and burned in the wasteland

of tracks and flattened wheat fields.

Mine is the marginal no-place

between suburb and bush,

stony places under electric pylons

or creeks under railway bridges.

Here come the fences

and the grass seeds and the parcelling,

the street lights and the sprinklers.

But a mile ahead … |

[Above] The End of the Road (Photo by Warrick Wynne, 2004)

It was the edge of the suburbs, a kind of no-mans-land between the straight lines of the streets and avenues and the almost borderless world of the bush. It was an anarchic place where paling fences in a row marked the edge of the rule of domesticity and order and where old barbed wire fences, dry-stone walls or lines of pines marked the end of an older order.We would roam the no-man's land between progress and annihilation, a child's frightening paradise. In Mornington the change seems to be happening more quickly, or perhaps I'm merely old enough now to remember the 'before'. I walk to where the suburbs end today. The road has been punched into the landscape and it just ends.

|

I walk along the smooth new footpath beside the new road until they both abruptly halt, and the paddocks begin. The road and the footpath have been carefully constructed and they have made little concrete driveways marking out where each new house will eventually go.

I walk to the end of the new smooth bitumen, the white clean gutter where no water has flowed. Ahead of me are the old paddocks and the yellow expanse. This is how a road ends. You can see the colour of the soil that has been turned over ahead of it. |

[Above] The End of the Road (Photos by Warrick Wynne, 2004)

Along the edges of the new roads they have planted small gum trees. Some are dead already, but some are flourishing and one day some of them will grow tall and their roots will rise up and crack these new footpaths. There are few other trees in the new landscape. Here and there in the slightly older settlements, there are concrete slabs with PVC pipes poking out of them where the footprint of a new home has been made. These imprinted places are about to be filled with people's lives.

In many of the estates around here the power lines are underground to avoid the clutter of the older suburbs, but they have replaced them with English-style overhead lights, long and curved like old gas lamps in Piccadilly Circus. I wonder if it's an attempt to give these crisp new places a kind of elegance or whether there's a more unconscious desire to insert the European into the new and shapeless thing they have built. It seems like a military exercise to me as I watch. The forward scouts, the young men arriving each morning in trucks, the caterpillar tracks, the scorched and razed earth where the progress has been made.

Rarely, there are connections between the old shapes and the new. I notice in one of the older estates there is an established line of trees that once marked an old paddock line and they have been retained, or accidentally left, along the edge of the new road. Another fine morning I drive into the newest subdivision to where the road ends. I park on the new white 'driveway' of a house yet to be built. I am probably the first to park here though this will be the entrance to a home soon. The parents shall drive home from work and park here and walk to their house and their kids shall greet them or not.

It is quiet outside, though a couple of hundred metres away I can see the tractors working. I wait for the cloud to blow away to take a brighter photo. I am standing in a field with a road cut through it. A bird starts singing in one of the only two trees left standing. The old landscapes are disappearing; being over-run by the developers of new estates which impose a new and different landscape, of courts and avenues, or broad sweeping lines of the road, or short sharp corners, with no relationship to what came before it.

|

Exploring

Not the mountain ranges

or the ridges the explorers followed

in the major scales of things.

But the humbler folds and creases,

the unnoticed rises and falls.

I'm talking of the rise and fall of the breathing land,

the sub-soil, small faults,

the subtle falls across the lawn,

this is where the pine tree grew,

the line of sight to the sea.

You could be the first person to dig here,

this dark soil may never have been uncovered,

mounds raised for dams and diggings survive,

new trees grow, a shape is unearthed,

suddenly you know something

you didn't before,

in the minor range perhaps

moody, almost nostalgic,

but still can't explain.

The roads are elaborately, shamelessly ambitious 'Panorama Circuit', 'Summit Views'. Nothing of the past has been retained, no shapes incorporated. They have created a vast random-seeming grid you are supposed to lose yourself in. The small delineations and designs, the tiny water-sheds are being plastered over. I think it's a loss. I think those shapes were important. |

[Above] Shadow on the New Suburb (Photos by Warrick Wynne, 2004)

There is a science in all of this design of course. Roads and their rules, the construction of housing subdivisions. There are regulations and regulations, principles and belief systems and they've evolved over the years.

The current fad here is for self-contained, enclosed developments with few entrances into the major road grids. Small house blocks, random curves, a maze. In the seventies, some of the developments around here contained only one entrance and exit, becoming isolated, insular little communities. The widths for streets, walks and pavements are based on the volume of traffic expected. The flow of the traffic is planned and designed. Courts are popular, and narrower roads to slow down traffic or stop them completely. One pleasing thing in the new designs is the number of walkways and bike-paths that weave through the estates; there are even places you can walk or ride where you can't drive.

But there is a stunning homogenity about it all too and there's no guarantee that this new brand of labyrinth will be any more successful in connecting communities with their landscape or each other. There is a brand new primary school which is already struggling to cope with the demands of young familes, and there will need to be new public transport resources in an area already hard pushed in this area, and the provision of health care, public spaces and other infrastructure, or this place is in danger of becoming self-contained and isolated, disconnected from the old town of Mornington and its traditional Main Street. I have little hope that this place will be able to forge some identity of its own out of all this.

Maybe some of my regret is nothing more than romanticised nostalgia. Not even logical. After all, this landscape has been changed before. The farmlands and the farmhouse and the cows and the windmills replaced something older and invisible now. The Mornington Peninsula, with about 175 km of coastline, is largely gently undulating country, with the highest point just 300 m above sea level. Before it was cleared for fire-wood, carved out in the southern areas from around 1850, most of this land was open forests of Drooping She-oak, Manna Gum and Coast Banksia all along the edges of Port Phillip Bay. Even the labyrinthine ti-tree paths to the beach are not ancient, though they ring for me with the tactile, the aroma of holidays by the beach as kids at Sorrento. The ti-tree came later too, replacing the She-oak.

And before the Tucks, the McRae's and the Balcombe's, and the others who got naming rights, Aborigines of the Bunurong tribe lived here, perhaps 700 or more of them, following their own familiar pathways up and down the Mornington Peninsula. It's likely that some of the original roads followed earlier dray routes, which were built on Aboriginal walking tracks. Either way, these inhabitants were pushed aside well before the 1850s and few traces remain apart from the shellfish middens, remnants of favourite places where food was plentiful.

|

Shells

At the end of my street

blackened mussel shells

layered under earth

on the track to my beach

I read Gwen Harwood

about Oyster Bay

without connecting;

is this what dispossession is?

Walking down the path to the beach at the end of my street a few years ago now, I noticed for the first time this charcoal-looking sand, the empty shells high above the high-tide line embedded in the earth, of a midden not a kilometre from where I live. I was shocked. |

[Above] New Shapes (Photo by Warrick Wynne, 2004)

The land was carved up for pastoral stations first, then agriculture as the demand for produce from nearby Melbourne grew, first in the form of firewood for the bakers' ovens, then sheep and cattle for food. Later, apple orchards thrived. John Brunning of Somerville pioneered the Jonathan apple which became a world favourite. As early as 1886 Somerville apples were exported to the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London and (a historian noted) 'established Somerville in the eyes of the world'. In 1932 a case of apples grown by A E Dennett of Somerville won the "Apples for King George W' Blue Ribbon at Melbourne Town Hall. The annual apple show in Somerville Fruitgrowers' Reserve ran as the largest show in the southern hemisphere from 1895 to 1939. How could they imagine it would all end?

Peninsula Pastoral

The apple has been replaced by the vineyard

and the stenciled pine boxes by the French oak.

They are bulldozing the orchards into piles

and the sign-writers are learning to spell 'boutique'.

Everywhere they are planting treated pine in long rows

and threading strands of silver wire for grape vines.

Some place else has been turned over to food,

and this place is losing its connection with itself;

somewhere in a forgotten field

that nobody owns,

rows of apple trees

grow wild and bitter.

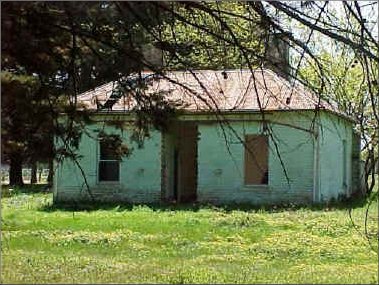

After World War II the era of the apple orchards began to fade. Big blocks were sliced up for house lots or, more recently, replaced by the ubiquitous 'boutique winery'. One day I watched a bulldozer casually uproot a grove of fifty year old apple trees, leaving them upended in a pile to be burned. There were farm houses too of course. They were mostly dismantled or moved or abandoned as the suburbs advanced. I would pass a couple of these empty houses regularly, watching the way they seemed to sag and fall with the absence of their occupants.

|

The Empty House

As soon as the heater stopped

the room began to cool,

suddenly, the cold could be felt

pressing in from above

and outside.

As soon as he left the house

the windows broke,

possums filled the roof

the verandah sighed with relief

at not having to hold itself upright,

like a man unbuttoning his belt

when the visitors have gone.

As soon as he left the garden

the weeds burst through

in sudden yellow flower,

the roses winded round themselves

intricate and thick as a hedge of thorns, |

[Above] Abandoned Farmhouse I (Photo by Warrick Wynne, 1999)

|

and the place became invisible,

the paths blurred

and the driveway

caved in with ti-tree;

even local people forget it had been there,

things rested.

Talk to anyone around here about the spread of the suburbs and they'll shrug their shoulders with regret and resignation. 'That's progress', someone said to me the other day. That explains it all, and it's not as if Mornington is the only place affected. 'The Age' newspaper has been running a series on coastal towns, and the pressure of development everywhere. 'Anglesea is lucky', someone wrote, 'there's no room to grow'. |

Abandoned Farmhouse II (Photo by Warrick Wynne, 1999)

It's something of a new belief, this one, that growth is to be avoided. I bought a faded old book from the 1940s from a stall in Mt Martha, called The Changed Village by Ursula Bloom, where she recalls nostalgically the village of her youth, now unalterably changed. Like Ursula Bloom, who included a hand-drawn map at the front of her book, I feel that I should be trying to preserve some of what's here; take photographs or write poems of the views before the estates came, so that people can see these lines as they were.

In A Place on Earth Scott Russell Sanders writes about revisiting his home, now flooded for a new dam: 'Before leaving the drowned woods, I looked around at the ashen stumps, the wilted grass … This ground was lost … but other ground could be saved, must be saved, in every watershed, every neighbourhood. For each new home ground we need new maps, living maps, stories and poems, photographs and paintings, essays and songs. We need to know where we are, so that we may dwell in our place with a full heart.'

Views of a Crest

What the Aakron Construction Company,

with their industrial yellow

matchbox collection

are walling in or walling out

is just landscape.

Outside, redundant contours

rolling lines,

sweep of distance

where the creeks went.

Inside, the fashionable curve of a future road

altered lines

grids of quarter acres.

Enter the old paddock

via the new brick gateway.

Cresta views is perfectly flat.

You don't get the name at all,

until you see a crest in the distance.

That's it: there's a view of a crest.

The landscape around Mornington is being flooded and drowned just as irrevocably and no poems or digital photos or hand-drawn maps are going to help.

[Above] Streetscape with Underground Power (Photo by Warrick Wynne, 2004

The landscape is being overlaid with bitumen: I once had a brochure someone gave me advertising the subdivision of the street where I live now; the old style beach cottages, straight grids of the 1950s. I wish I still had it, with its 50s iconography, smiling families, men in suits with briefcases, no hesitations or regrets. I asked the Council and Library if they keep that kind of stuff, but they don't.

An old neighbour told me about the early days in Mt Martha, the subdivisions of the 1950s and the casual spruiking for sales. He remembered a real-estate agent walking along Mt Martha beach in the summer, approaching families on the sand and offering them blocks of land for 'fifty quid'. Those straight-line developments maybe weren't much different though they lacked at least the blatant hypocrisy of the new names and their false claims to inner calm: 'Serenity Way', 'Reflections Way', 'Honour Place' and most improbably, 'Zen Rise'. The building of the new community, its self-contained, complacent disregard for the past, is something that always concerned me.

|

Lakeside

At Lakeside Estate,

ideas of walled cities:

encirclement, containment.

The fertile lake at the centre,

decorated with pet ducks,

slaughtered ritually for fun

by bored teenagers,

the circling street,

brick veneers stringing out

in the songlines of Bentleigh,

weaving from the centre

to the wilderness of the paddocks

and the edges of known places.

Here are layers

over-riding the boundaries of the fields

natural selections

becoming blurred

beneath the model of the birds;

that broken line of pines

was a windbreak once

and miles from anywhere.

Here again

are the concentric circles

of tradition,

migratory patterns;

young families

streaming into the new walled city

where explorers stood

and wild ducks flew. |

[Above] Hills Hoist (Photo by Coral Hull, 1992)

What can you say about all this? I miss the shape of the place, but walking around the new estates a month or so after the road has been pushed through I can't help sense also the irrepressible and infectious desire for life and expansion. It's like I'm walking through the construction of a giant Hollywood set; it all seems so impermanent and improbable somehow and yet maybe some great project will come out of it all. The bustle, the serious intentions of building new families in all their homogeneous diversity, reminded me of Henry Beston's writing in his 1920s book, The Outermost House where he lived on the beach of Cape Cod for a year, watching nature in all its desire to re-create itself and perpetuate itself, amazed at the insistent and incessant battle to live; 'creation is here and now', he wrote.

And here too in these earnest purposes. I walk the new footpaths where the houses are sprouting up. A man is trimming down a pallet with a hand saw, fitting it to some purpose he has devised; across the road two builders are crouched under a frame they have nailed together. In the cool morning air men in caps are building picket fences and listening to breakfast radio.Down the new 'crescent' a truck load of windows arrives, clear panes, meticulously assembled. Everywhere there is intense seriousness and activity and the empty frames of the new houses are strangely beautiful, the way they throw the sticks into the sky, the roofs full of wood against the blue. Before the tiles go on these rooves could be spires.

[Above] Making The Road (Photos by Warrick Wynne, 2004)

One developer has been convinced or compelled to wrap the long footpath around one of the few existing trees; a messmate gum. The straight line is suddenly diverted; something from before has been retained.The first completed house has still got Christmas lights draped across its entire front; is this going to become a tradition here? Outside another completed house down a new court, a police car is parked and two uniformed officers are speaking to someone seriously through a screen door. Lives are unfolding already.

I feel like I'm watching the three episodes of 'Back to the Future' simultaneously, the old land, the new land, the future promise of home. What you don't see is the rise and fall of the land any more. Occasionally you get a long avenue and you can again see the old curvature but it's a glimpse and it's gone in a sea of new rooves. I walk to the edge of the world. At the outermost house, the washing is swinging whitely and wildly on the new Hills Hoist, shining steel and white against the green and the yellow.

Bibliography:

Ames, David., [Online], "Interpreting Post-World War II Suburban Landscapes as Historic Resources". Available from the Internet, 1st November: http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/publications/bulletins/suburbs/Ames.pdf (2003)

Beston, Henry., The Outermost House, Henry Holt, USA. (1928)

Billica, Karen Paulette. [Online], "Identity Expression in Three Single-Family Residential Subdivisions in Bellevue, Washington"

Available from the Internet, 1st November: http://www.caup.washington.edu/larch/academics_research/stu_research/theses/billica.htm (2003)

Bloom, Ursula., The Changed Village, Chapman and Hall, London, England. (1945)

Calder, Winty., Peninsula Perspectives, Jimaringle Publications, Melbourne, VIC. (1986)

Duany, Andres et. al., Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream. North Point Press, USA. (2000)

Gentzsch, Velma. [Online], Our Endangered Farmlands available from the internet 12th January: http://www.greenfoothills.org/news/2001/08-2001_Farmlands.html (2004)

Hast, Thomas. "Alive and Well and Living in Mornington", Mornington Leader, Melbourne, VIC. (1979)

Jones, Michael. Frankston: Resort to City, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, Aust. (1989)

"Mornington Peninsula Shire Mornington East: Planning for Growth" (2000)

Moorhead, Leslie M. Mornington, "In the Wake of Flinders, Shire of Mornington", Melbourne, VIC. (1971)

Port Phillip Conservation Council. [Online], "Safety Beach Marina" available from the internet 12th January: http://home.vicnet.net.au/~phillip/i_mztass.htm (2004)

Sanders, Scott Russell., edited by Mark Tredinnick, UNSW Press, Sydney, Australia, p. 215-220 (2003)

Sault, Tom H., "The Mornington Peninsula: Through the Eye of a Naturalist Trust for Nature" (Victoria), Melbourne, VIC. (2003)

About the Writer Warrick Wynne

|

Warrick Wynne has been writing poetry for over twenty years and has been published in a wide variety of journals in Australia and overseas. Many of his poems centre around notions of landscape and the natural world, particularly rivers and streams, the coastline of Port Phillip Bay and the ocean. Other recurring interests are the landscapes of suburban edges and the past. A member of the Poets Union and the Fellowship of Australian Writers, Wynne is also an assistant editor of Famous Reporter magazine, poetry correspondent for The Mariner (a Mornington Peninsula independent newspaper) and convenor of the Education Committee of the Poetry Australia Foundation. His poetry has been recognised with several awards including the Northern Territory Red Earth Poetry Award (1992) and the Max Harris Poetry Prize (2003). He was awarded an international fellowship from the Australia Council (2000) to work on a poetry project in Ireland. Wynne lives and teaches English on the Mornington Peninsula, south of Melbourne. |

[Above] Photo of Warrick Wynne by Phoebe Wynne, 2002.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.9 (March, 2004) |