DAZED AND SILENT IN HISTORY

By Chris Mansell

[Above] This basalt scribe is in the Egyptian museum of antiquities in Cairo. There were many other scribes, all in the same position, and all looking similar though in different media. I bought a small basalt replica of this one to put on my desk: a tenuous link with the old writers.

(Photo by Chris Mansell, 2002)

I stepped out of the hotel and fell in love with Cairo. Large, dirty, chaotic and there. The air was dry as central Australia and the heat made me think I was at home though the El Dokki where I was staying looked as unlike any part of Australia as it could do. An unlikely home: a 17 million strong mostly Muslim city but a city with both discipline and disobedience. Repression and joyousness. Who could resist a town that listened to the call to prayer and paid no attention at all to traffic rules, where the people were friendly in three languages - and not just the ones who thought they might make a sale (though there were plenty of those) but where you hardly saw women on the streets at all and began to feel not just a foreigner but an alien.

This was a quick tour of Egypt and my job was to present workshops and read people's work. There were seven workshops: two in Cairo, several on the cruise ship as we floated down the Nile, one in Aswan. I wasn't going to teach the tour participants anything about Egypt. The country itself and the guides would teach them that and, as is usual at the beginning of a workshop series, I was ambitious: I wanted to lure them into seeing. As it turned out some would be lured, others not. Compromises had to be made. It is always the case, so I should know better. People say they enjoyed it and they certainly wrote things - poetry and prose of various kinds. This was a holiday for them after all, and not everyone believes that poetry can save the world. There was no room for passing and failing. I did, however, spent an intense time with young playwright Guinevere Rose on the top deck of the Soleil, broiling in the sun. It was a strange disjunction of time and place: we were deep in discussion and reflection on the court of Thutmoses III and the realities of writing for the Australian theatre while the other tourists, mostly French (in ugly swimming costumes and crimplene shorts) tried to look rich and cosmopolitan, and failed. These French had come to cruise, not to look at ancient objects or worry about ancient intrigues.

Most of my life I have spent not feeling at home anywhere. Even where I was born. There is something, however, about being so remote a familiar stranger that settles you. It's as much part of our heritage as ancient Greece - a half-baked cultural heritage with which Australians are very familiar. Most of us are neither connected to our Aboriginal heritage nor to our immigrant antecedents, nor much to our philosophic or cultural roots. Like most literate people I knew things about Egypt - most of them wrong - and like most I wanted to see for myself the artefacts. Pyramids, temples, statues, obelisks.

[Above] Kom Ombo temple. A place of healing and medical knowledge. (Photo by Chris Mansell, 2002)

What I actually found most interesting were the small things: the depiction of the ancient Egyptian calendar, the medical instruments depicted on the walls of the temple at Kom Ombo - the kindliest temple I visited. The evidence of the hands of the people working the limestone and granite. And the very large things: the same sorts of behaviours in stone used today to manipulate the populace. When you walk into Karnak temple near Luxor, between the rows of sphinxes and past the obelisks erected by Queen Hatshetsup which would have originally been topped with electrum to catch the sun and impress - and possibly to keep time (Egyptians understood the sidereal year and counted a year from when Sirius rose above such an obelisk) - you look far into the distance and see where the religious ceremonies would have been conducted. Not close to the populace but distantly for most. Lit up in a theatrical show of mystery and power. Or so I'm told.

You know these terrible days that you are subject to an emormous degree of propaganda but on temple walls there is a lot of smiting going on. Ptolomy XII grasping his enemies by the hair, Ramses II doing violence to his opponents at Abu Simbel. Subjugated people with their hands bound behind them or being thrown into grievous disarray. The walls say nothing of the 'collateral damage'. It seemed familiar.

Egyptians are very proud of their culture - the stones anyway. I tried looking for a 'library' (aka bookshop, there is no distinction between the two) which would sell some Egyptian poetry in translation. I could find Arabic poetry (from elsewhere) in English and French but not a word of Egyptian poetry in any language. (I had been hopeful that I could find there things that I was not able to get here or from the net - but there are leads for next time which I'm eager to follow up). I read instead Naguib Mafouz - the most famous Egyptian writer of the modern era and its only Nobel prize winner. My favourite is the brilliant Cairo Trilogy (I set aside a couple of weeks for dedicated reading). It is personal and political and set around WWI and II. Our glorious young soldiers who went there to defend the Empire do not get good press and everything we always suspected about the British is reflected in Mafouz's account of their occupation. Most of those on the trip had, back home, a picture of young men with silvered out eyes in front of the Great Pyramid or in the trenches doing their bit for the empire. I'm not sure how many changed their views of the role and purpose of those soldiers.

|

Call to prayer

sound and light at Giza

it is night and

the buses have arrived

and the tourist police

are out

pistols on their hips

the hawkers ready

the light show is

about to begin

colouring Cheops

and the others with mad green

and orange lights

and us in black

the Sphinx rises out

of the dark |

[Above] Karnak temple at Luxor, at night. (Photo by Chris Mansell, 2002)

|

suddenly

like a big sister

wanting to know

what

you are doing

in

her

room

all cameras face forward

and the BBC English version

of Egyptian History

with heroic orchestrals

flies up fiercely

the golden falcon

of el Misr |

[Above] Sphinx and pyramids at Giza. (Photo by Chris Mansell, 2002)

|

rises up beyond

the stone

you feel her wing beat

against your face

the stones are huge

elegant

an architect's dream

but the history

is most forgotten

the pharaohs and their queens

the queens and their consorts are

shamed in their loss

and over the adobe houses

the call to prayer slides through

the air

the imam fills the spaces

with his perfumed voice

and the one god

Amun Aten Allah

breathes the sparse air |

[Above] The el Dokki region of Cairo. The sky is full of dust and the roofs are full of satellite dishes - which more or less sums up the extremes of Egyptian life. (Photo by Chris Mansell, 2002)

When you stand among the stones of a temple, made or modified by the Greeks, Romans, Persians, Turks, Arabs and by the religions and beliefs they brought with them you understand the richness of the place. I have stood in the remains of a temple of the middle kingdom and looked to the right and seen how the Christians defaced some of the more ancient relics: where images had been scraped off the walls, where cooking pots had blackened the images painted on the ceiling, and then looked up, eight metres, and seen a mosque. Once the ground on which I was standing had been covered with debris and deep dust. And the Muslims, perhaps with some memory that an ancient temple had been in this location had built on top of it. What had been recovered was all three. I was standing in an illusory time: at this very point is the confluence of Egyptian history: ancient and modern, including the modern religion of conservation and tourism.

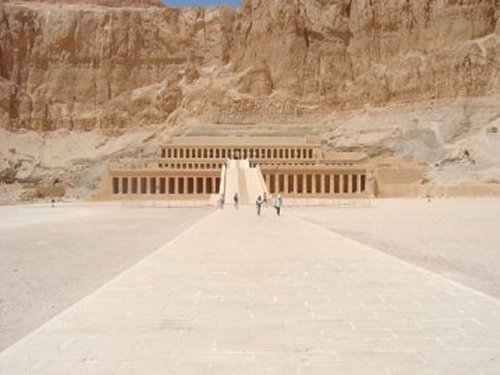

[Above] At the reconstruction of Queen Hatshetsup's temple. (Photo by Chris Mansell, 2002)

Once, the people had carted off the stones to build walls and houses (though most are mud brick). Egyptians tsk over this today, and are irritated by the people who live between the Valley of the Kings and the Colossi of Memnon (or rather of Amenhotep III as I learnt to correct myself) who will not move so that the land they live in could be dug up for archaeological treasures. This is seen as a huge selfishness. The people there say they are the original Egyptians and that they will not be moving for anyone. The landscape around them is unbelievably inhospitable. Fabulous tourist roads cut through decaying limestone hills with not a breath of green on them. The people there are artisans still. You can buy handmade alabaster or basalt objects. The only things that seem modern apart from the roads is the credit card facilities and the ubiquitous availability of 'pepsi lite' (Diet Coke).

The Nubians who come from the south are also presented as selfish. When the Aswan Dam was built and their villages - complete with temples, mosques, churches, houses and fields was flooded, those who where not grateful to receive relocation and education elsewhere were seen as trouble makers. The temples of Ramses II and Nefertari's temple to Hathor were moved to higher ground at Abu Simbel though. Others are more genuinely inconvenient. The Israelis are still deeply suspect because they have, more than once, offered to blow up the dam which, in addition to being a devastation to the confidence and economy of Egypt, would be likely to kill (it has been estimated) between 30 and 50 million Egyptians in the resultant flood. I was proudly told that since Egypt stood up to Israel there have been no more such threats. A Peace Accord is not mentioned although of course it appears in even the most cursory of historical overviews. Many Muslims were not pleased to have such an agreement. If you look behind you when you arrive at the airport at Aswan you will see underground hangars and perhaps a fighter plane or two sitting at the ready on the tarmac. Egypt devotes about 4 % of GDP to defence (compared to Australia's 2%). If you look you can see that security is an issue - everywhere. Airport-style security at monuments; a gun tower at the railway station. Mostly you don't look, and the Tourist Police in their white uniforms are young and seem friendly - and carry small pistols attached to their belts.

[Above Left] Part of the unutterably dry Valley of the Kings. (Photo by Chris Mansell, 2002) [Above Right] The temple of Horus at Edfu. (Photo by Chris Mansell, 2002)

You know you're in a different mind set here. As different as, say, the mindsets between those who live in Melbourne and those who live in Darwin. And you cannot help but reflect on the lazy comfort back home.

As a poet you make connections all the time. Try to understand the continuities and the discontinuities. It works this way at home as well. In Australia you know that all around you is an invisible history. You know the barest minimum. That this mountain, once a volcano, was once inhabited by a wild and evil fellow much feared. You have seen photographs of the carvings in trees which signified much, though you don't know what and no one can tell you with any certainty. You can't feel at home because you don't know how home is delineated - what made it up, how it comes to sit and mean what it does. You've learnt to distrust contemporary glosses because they've let you down before (you remember how you learnt of Australia being 'discovered' for example) but you have no other ingress to your true culture. You're a stranger who should belong. I knew more about Egypt's ancient history than I know about my own country's.

In the Egyptian Museum of Antiquities in Cairo there is, high on the wall, a glass case with two sets of boomerangs in it. One set, comprising returning and non-returning boomerangs, is labelled 'Australian Aboriginal', the other set, undated, were ancient Egyptian boomerangs. I'd come on them by accident among the mummies, basalt, and gold. I searched around trying to find some more information about this display. Cairo museum is famous for not being over-informative with its labels - it's a wonderfully old-fashioned place. It is a pleasure to explore - nothing interacts. While I was looking around a guide came past with his entourage and told them that the Egyptians must have gone to Australia to teach the Aborigines how to make boomerangs. I was a bit taken aback. I tried this out on some Aboriginal friends when I got home. They fell about laughing. As ancient as Egyptian culture is it seemed unlikely to them and to me.

[Above Left] A part of Karnak temple at Luxor by day with people for scale. (Photo by Chris Mansell, 2002) [Above Right] The beautiful Ramses II at Memphis, once the most famous capital of the ancient world. Today only this huge and beautiful statue of Ramses II and an alabaster sphinx remain. It's assumed that there are other antiquities buried in the surrounding farm land. (Photo by Chris Mansell, 2002)

Back at the hotel in Cairo, one of the tour participants tells a visiting expert 'of course, our culture is very new, 'They've done an excellent job in the Australian propaganda department. I humphed and bridled, which was met with blank astonishment by most. They had no idea what the problem was. The problem was in defining culture in terms of artefacts. The bigger the artefact the better the culture. Fascinated as I was with Egyptian culture, and I was deeply fascinated, it reminded me that, at home, my house was on land occupied for thousands of years by a people whom I might run into on the street and whose language, like the language of the ancient Egyptians, had effectively been taken from them. Egypt is a living illustration of the wash of history; of the cycle of destruction, rebuilding, hubris and accommodation of cultures. Where I came from, as far as I knew, was a place where until recently, stability ruled most of the time. A condition we say we aspire to.

The truth is I spent a lot of time looking at very large buildings and being blown away by them: their longevity, their subtleness, their grandeur, their engineering, their social/religious/political intent (in so far as I knew it). Suddenly, it would break in on you. Luxor is Thebes. This is Memphis - the original one. This is the great Karnak Temple. As if suddenly myth and had become reality: like a poem does.

It is impossible to take in a whole country in a visit, but it is possible to fall in love in an instant - having more to do with the sounds and smells of a person or place than in rational thought.

Egypt is a theoretical country. Theoretically, it is full of antiquities and has a history longer than most of us can imagine. In theory it is Egyptian, not particularly Arab, though it is that too. It is a place in the mind of dignity and the kind of slow procession of pharaohs. Like very few other countries we have one or two images which are supposed to sum up the place: a pyramid. Maybe the head of Nefertiti, or Tutankhamun's golden mask. One or two other bits of monumental masonry. Pictures in children's books and colouring in the Nile (the Blue Nile and the White Nile and the Source of the Nile). Probably we learnt the word 'delta' when we learnt the word 'Nile'. An archetypical river.

It's a shock to see the real river. There is nothing that grabs your eye about it really. It's a river. A big river. And one that has played such a part of our cultural heritage that others on the writing tour would, from time to time, say to to themselves or each other 'This is it. The Nile. How amazing', as if for the first time they had realised that this was in fact an actual hydrographic feature rather than an ideal or an idea.

|

The Nile at Aswan

in the dome of air

sane men are dead

and the desert sweeps

their bones I learn

their names

habihotep

ikhou

habi

senabi

sennefer

the dome of its sufi

exile in the dust

as blank and empty as

the desert stones |

[Above] The Nile is a working river. Rural people still use the felucca to transport people and goods on the water. The fertile Green here is very narrow. (Photo by Chris Mansell, 2002)

|

the tombs are lit at night

for tourists

midnight bathing

with their young men

on negligent cruise ships

their limbs alive and succulent

the desert scent is water

and dust the scent

of a young man

and the dead too

are indifferent

just as poetry deserts

when the crucial eye

cares too much

* * * |

[Above] Chris Mansell on the nile near Aswan. A Nubian boatman in the background (Photo by photographer unknown, 2002)

|

really it's a love affair

with a river and you hardly

notice me another western slapper

and the world is wide after all

your dust

hangs in the pale sky

I wake each morning

with your stories and your monuments

I taste your dust

touch your stone lips

I say

how's my enemy today?

fuller than I wanted your lips to be

more luscious than I would

have liked |

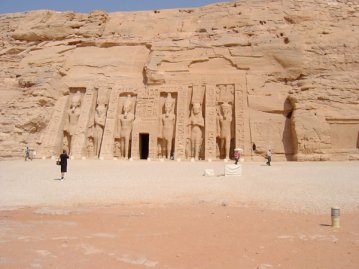

[Above] Temple of Hathor at Abu Simbel. Four of the statues are of Ramses II and two are of Queen Nefertari (his wife). The smaller figures are of the children. Each statue is about ten metres high. (Photo by Chris Mansell, 2002)

|

oh ramses

because every lover

is an enemy

whether stone or river

or scented flesh

I am a stranger

and you hardly smile

your kohl eyes reproach

my fair skin

The problem of Egypt for writers is that it's so done that anything you've got to say feels like a presumption. And it is, more or less. In the words of any number of working class Australian schoolgirls - Who do you think you are? |

[Above] The Eye of Horus, detail, from the Temple of Horus at Edfu. (Photo by Chris Mansell, 2002)

You can take the short route to understanding. You can keep a very detailed journal and many pictures, and write small poems on each event or sight you encounter. The poems will be proficient and, possibly, charming. Egypt, though, requires you to go back and to build an understanding of the texture of the stones. Get to know the people. Find the women. Speak to the poets. There are more questions than there are answers. There's no doubt that a lot will turn up later in what I write, but, for the moment, a few poems, a few sketches (verbal and visual) anchor my thoughts about the place. I can't wait to go back - and I will. Probably with another writing group, maybe in 2004. In the meantime, I'm planning other writers' trips - to Rajasthan in November 2003 and to South America in 2004.

About the Writer Chris Mansell

|

Chris Mansell was born in Sydney, Australia. She has a Bachelor of Economics from the University of Sydney. In 1978 she founded the literary magazine Compass poetry & prose with Dane Thwaites which she edited until 1987. Her collection of poems, Shining like a Jinx, won the Amelia Chapbook Award, USA. From 1987 until early 1989 she was a part-time lecturer in creative writing at the University of Wollongong. In 1989 she was a full-time lecturer in creative writing at the University of Western Sydney, Macarthur. She has lectured in writing at the University of Wollongong and the University of Western Sydney. In 1993 she took up a Writing Fellowship from the Literature Board of the Australia Council. The following year she was awarded an Australia Council Community Writer's Fellowship in the Shoalhaven district of New South Wales. Her collection of poems Day Easy Sunlight Fine was short-listed for the National Book Council's Banjo Awards. She has been mentor to a number of Australian poets and is publisher of PressPress. |

[Above] Photo of Chris Mansell by Willian Sturgess, 2000.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.8 (September, 2003) |