THE TROUBLE WITH HARRY

By Liz Hall-Downs and Kim Downs

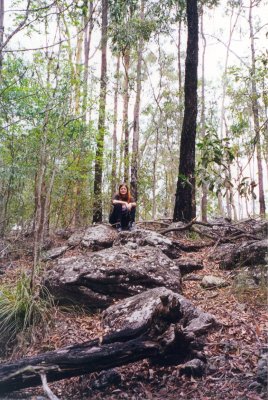

[Above] Feeding Harry The Currawong (Photo by Liz Hall-Downs, 2003)

In the past, the vast majority of my writing has been concerned with, and influenced by, a largely urban lifestyle in which other beings/species hardly feature. Under the influence of this environment, the self, other people, and the human condition become the main subject of the work. The natural world exists as a kind of 'bolthole' from the stresses of this lifestyle. Actually living in the bush changes all that. The number of other beings we encounter in a day may be similar to the numbers an urbanite encounters, but other humans actually feature very little in our daily lives. A large variety of birds, mammals and reptiles, however, are a constant feature of each day, and their seasonal movements and behaviours cannot fail to influence - and even shift - our view of the world and our place in it.

For me, this means that instead of seeing myself as an artist interpreting and reflecting on the world, I begin to view my existence as part of a totality of life - we are not better, or worse, and certainly not more valid or important than the creatures we coexist with. We do, however, have the power to influence the lives - and indeed the survival - of other species through our actions or inaction. On a practical level, this means habitat preservation; on a creative level, it translates, for me, as a desire to document these lives and reinforce the positive effects of daily contact with the wild, in both art and life.

|

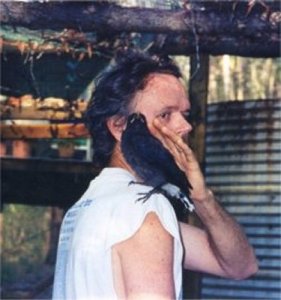

My own health dilemmas have necessitated this shift to a more 'natural' lifestyle. For the past 22 years I have suffered from the autoimmune disease Rheumatoid Arthritis and, in the past decade, have had to contend with an increasing level of disability. Stress of any kind tends to worsen the symptoms. As RA primarily attacks the small joints of the hands and feet, my own writing output has been severely curtailed by the ups and downs of my disease, and the pursuit of better health and less pain has become a daily challenge. The frustration of this situation is exacerbated by often being unable to drive, and I am less able to participate in the public business of 'being a writer' by attending readings and festivals. From this position, I reflect back on all my years of frenetic activity as a poet with a kind of bemusement.

I believe the ego politics, competitiveness, and sometimes downright bitchiness, of the literary scene, is not at all conducive to the production of quality work. Publishing's increasing emphasis on marketing the charisma and media-friendliness of authors ahead of their actual work seems to have become endemic. The internet has become a lifeline to those of us who are producing writing that can't find an outlet because it's not in the style of the latest 'fad'. |

[Above] Liz Hall-Downs at "Euphoria" (Photo by Kim Downs, 2000)

Here in Brisbane, the current 'fad' is 'young adult' writing and anything that emulates the whimsical, self-deprecating novels of Nick Earls as publishers seek to cash in on earlier 'successes', measured purely in terms of book sales. At the same time, there's been a noticeable tendency amongst some of our young poets to embrace incomprehensibility and obscurity, dotted with veiled references to 'famous' dead poets, in a cynical effort to prove 'credibility'. Meaning, and communication of ideas, all seem to have taken a back seat to a kind of 'cleverness' that leaves many readers wondering if modern poetry has anything of relevance to offer, as these ambitious young poets hide their true feelings behind endless complex metaphors and set themselves up as a kind of elite who are too complicated and erudite to be understood by the average, educated reader.

In such a climate, to continue to write in one's own clear voice, to concern oneself with the 'state of the world' instead of just the inner machinations of one's own psyche, and to cultivate literary friendships instead of just 'contacts', seems an increasingly radical approach.

Living in a forest is something I, along with my partner Kim, have always wanted to do. But, like most of our spoiled, urbanised generation, we have become accustomed to modern conveniences, and this has influenced our choices. As younger people, we have both 'dropped out' of society many times, living in various rural or bush shelters with few conveniences. It's a lifestyle I recommend to everyone, even if only for a short while. From an environmentalists' standpoint, it's good to be reminded that electric lights, hot running water, and television are relatively recent additions to our lifestyles. It fosters an awareness of consumption which, in turn, influences how lightly we tread upon the earth.

[Above Left] View of "Euphoria" (Photo by Kim Downs, 2003) [Above Right] Alice the Galah takes a sunshower (Photo by Kim Downs, 2001)

As creatives, so often dissatified with the sterility and meaninglessness of modern life, it's conformity and enforced values, we have both long sought authentic experiences and lifestyles from which to draw inspiration. In our case, this has landed us on a small forested acreage property in south-east Queensland, where we have been 'caretaking' and attempting to improve the habitat value of the bulk of 9.3 acres. The property is undeveloped, with large mature trees, understorey and a groundcover of native grasses. Its conservation values have been described by Land for Wildlife as "good condition of the bush and diversity of habitats including seasonal watercourse and rocky outcrops. Good bird diversity (40+ species)". (LFW Assessment, Nov.2000)

Though many of the larger trees were taken some decades ago, enough large mature trees exist to provide tree hollows for the many mammal and bird species that rely on them, and we have been fortunate to witness the breeding cycles of many creatures, including king parrots, kookaburras, possums, and gliders. The tall open forest contains specimens of spotted gum, ironbark, blue gum, tallowood, bloodwood, brush box, stringybark, casuarina, and paperbark. A good variety of mammals (bats, wallabies, kangaroos, gliders, and the occasional passing koala) and reptiles (snakes, goannas, water dragons, bearded dragons) complete the picture. The past three years has given us ample time to observe the diversity and movements of the wildlife through this environment, and to note our own impact upon it.

Nine acres isn't much to work with, especially in an area of rapid habitat loss. As Brisbane's urban sprawl creeps inexorably towards the NSW coast in an attempt to accommodate the hordes of people moving to Queensland from the southern states, vast swathes of habitat are being lost to housing development. Our immediate neighbours are mostly on five to ten acres blocks, and keep, variously: horses, goats, fowl of various kinds and the odd house cow. As a general rule, the trend here has been to 'tidy up' properties, removing native groundcovers and understorey plants and leaving only some of the tall eucalypts. The 'rural residential' nature of the surrounding area has changed noticeably to a more suburban ideal in just a few short years.

This attitude has been fostered partly by real estate agents, who seldom advertise the diversity of wildlife on a property, preferring to emphasise how neatly lawns are maintained and mowed - encouraging sellers to 'clean up' areas of leaf litter and fallen branches which house the bottom of the food chain (insects, frogs, small lizards, etc). It seems to us there has been a failure to recognise the enjoyment and value many people gain from living in a place of abundant wildlife, and that this is seldom used as a selling point.

|

Yet, a mere forty minutes drive to the north-east, in the Brisbane City Council local government area, fairly strict tree-clearing laws and newly-established wildlife corridors have become the norm. Brisbane prides itself on the diversity of wildlife still occupying sites in the city and surrounds and encourages residents to plant wildlife-friendly gardens. But it will take some time - and doubtless much further habitat loss - before such notions filter through to the more rural areas surrounding the State capital. Small-scale tree clearing is, sadly, some way down the list of current environmental priorities in Queensland, where the fight to stop the massive (and alarming in scale) broad-scale clearing of farmland is still being waged.

Within 10 kms of us a new development is taking over the scrub. At present it houses 5,000 people, with an estimated final population of 70,000 expected within the decade. It seems to us that, even allowing for public 'green space' in such developments, and the existence of national park and state forest areas, it is important for private landholders to preserve and/or create habitat if we wish to keep the current level of diversity. |

[Above] Tawny Frogmouths (Photo by Kim Downs, 2000)

All this sounds very hopeful and positive - and I confess to periods (particularly in the house construction phase) when it all seems like so much spitting into the wind. It could be that - as so many of us have seen in all our major cities over the past fifty years - that these are the last days of our particular piece of paradise existing as a diverse and natural wildlife habitat. It could be that urban encroachment will impact upon local numbers and breeding cycles to the extent that these particular kingfishers I look at today may be one of the last local pairs to face displacement - but displaced they will ultimately be.

Which brings me to the story of Harry. Harry is a pied currawong that we successfully rehabilitated and released over the summer of 2002-03. The photographs tell their own story, and I've left it to Kim (who features in most of them) to narrate the sequence of events in this rearing process. It's a nice story, of human-animal interface in a semi-wild environment, that serves as a reminder of what we, as conservationists, are trying to preserve. It also, however, raises some ethical questions regarding human interference with wild systems and how this affects the makeup of the ecology.

Whether or not to feed wildlife is one of the biggest issues. Recent surveys show that 38% of Brisbane households purchase food to give to wildlife. We know that amongst our immediate neighbours, the same magpies, parrots, kookaburras and currawongs visit each of their houses on a daily foraging round. It could be strongly argued that the local birds we humans regard as 'desirable' are already in a dependant relationship with us, and are relying on an ever-present supply of free food from any number of locations. But it's a tricky business that can pose dangers to the wildlife if not undertaken with a mindfulness of both the appropriate types of food to give and the effects of feeding on the animals' health, prevalence, and social organisation. For example, a recent documented kill of large numbers of rainbow lorikeets in this region was found to be caused by unhygenic bird feeders that had harboured disease (LFW, Note 20) - literally, these birds were 'loved to death'.

[Above] Brush-tailed possums (Photo by Liz Hall-Downs, 2000)

We may enjoy the brush-tailed possums that inhabit our block, but if we feed them, do we encourage an explosion in their numbers that might see other species displaced from the limited supply of nesting hollows? The complexities of such issues are endless, and have been the subject of spirited debate. Suffice to say that, for ourselves, we've decided to leave the land and its animals and birds alone as much as possible. Around the house, we do put some food out for the possums and currawongs during that particular time in spring when they all have young and are working very hard to keep them fed. We then slowly withdraw the extra food as the babies are leaving their parents so they get a chance to be taught how to forage for themselves. I'd stress, however, that this only happens with a very select few wild animals. The pet parrots we keep seem to attract others of their kind, but they only sometimes receive the pets' leftover seed husks. In the case of Harry, he was acquired because he left the nest too early, and his subsequent injury kept him with us for far longer than either of us would regard as ideal. On the upside, however, it was a chance to closely observe currawong development and behaviour, and to enjoy an engagement with 'the wild' that's all-too-infrequent in these fast-paced times. That he was able to form a kind of relationship with us, yet still be successfully released into the wild, reaffirms how adaptable wild creatures can be. It also begs the question of whether the creature itself is capable of 'enjoying' the relationship - the photographs indicate to me that Harry certainly did!

Kim Downs: We first spotted the pied currawong nestling, we later dubbed 'Harry', near the middle of October, 2002. We knew that his parents had produced offspring. We later found Harry had an older - more advanced - sibling, who could fly properly and remained in the canopy. But Harry appeared to us to have fallen out of the nest too soon. He was clumsy, had insufficient flight feathers to ascend back into the trees, and was obvious prey to any spirited crow, goanna, or even a desperate magpie. So, we made the decision to capture him and contain him for just a few weeks until his flight capabilities improved.

From observation of his parents - over several years - we had noted that they (dubbed Mr. and Mrs. Baldy) both appeared to feed their young primarily on insects, cherry tomatoes (pilfered from neighbouring cottage farms), bird seed, whatever food scraps they might have scavenged from our feeder and unknown other flora and fauna. In addition I had taken to sporadically leaving out inexpensive dry catfood for the currawongs and this was fed to the youngsters as well.

[Above] Lace Monitor (Photo by Liz Hall-Downs, 2001)

Catching Harry was relatively easy. We had seen him hanging around near our outside aviary/enclosed garden for about a day and a half. I chased him briefly. He became entangled in some bushes and I just picked him up and released him into the garden. The garden is enclosed in ½ inch square-mesh wire. I opened up a small panel near the ground and covered it so that Harry's parents could poke their heads through and feed. him. This they did, and they regularly visited him across the wire to comfort him and feed him.

After closer observation of Harry, it appeared to us that he was actually even more immature than we had suspected - particularly after spotting his older sibling whose wing and tail feather growth were weeks more advanced than Harry's. After much discussion, we decided to restrain him for at least a month and then re-evaluate. The problem was that we were leaving for four weeks over December. The way it played out was we kept Harry for the six weeks prior to our trip, and then enlisted the help of our neighbour to look after him until we returned.

During the initial six week period that we kept Harry, we took turns feeding him and attempting to interact with him in an effort to desensitize him to us enough to learn a bit about him before we released him. His parents continued to feed him as well. Aside from cat food, we also fed him the occasional strips of raw meat, tiny strips of apple (again, from observing his parents feed apple to their young), and sometimes raw corn.

Pied currawongs (like kookaburras) cough up little compressed pellets of undigested food on a daily basis. They often disgorge them just before eating afresh after a break. We often find these pellets on the possum feeder and I've inspected them many times. They appear to contain such items as insect legs and carapaces, undigested seeds, apple peel, sometimes wisps of fur (from captured rodents?), twig and leaf matter, the seeds from native vines, and copious unidentifiable (to the naked eye) sods and detritus.

|

Even as a youngster, Harry was already absolutely smitten with every insect within perview. He caught mosquitoes out of thin air with a casual snap if they strayed within cooee of his beak. He tasted, spat out, and sometimes ate various ants that took his fancy. From the naturalist literature, currawongs are notorious for eating bull-ants. Harry also fancied dragonflies, most butterflies, beetles, spiders ... pretty much any insect was, presumably, worth a taste. This observation corroborated the behavior of other currawongs which, in our neck of the woods, seem primarily interested in perching strategically on a high spot, only to swoop silently down and crash into the forest leaf litter to surprise whatever insect, skink, worm, mouse has had the dash to stick its head up. Insects seem to be their primary passion. Harry had it hardwired in; not even his mother had to teach him what insects were for. |

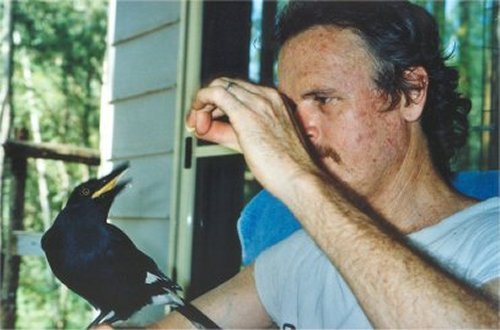

[Above] Kim and baby Harry (Photo by Liz Hall-Downs, 2002)

Harry was becoming pretty friendly after six weeks in captivity and was just taking to sitting on my shoulder and jumping on my extended arm for a feed when we went on holiday for the month over Christmas. During this time he was looked after well by our neighbour, Maude, who had to contend with four-hourly feeds and a lot of vocal begging. He was confined to a cage for this four week period and upon our return I released him back into the enclosed garden. By this time he could fly pretty well and had grown considerably from the time we had captured him - some 10 weeks previous. We decided to keep him captive for two more weeks and then release him.

Then, with only a week or so to go, I found him one morning with an injured leg. His right 'knee' joint was bloodied and swollen and he was holding up the leg. I can only think he either scraped it on the cage wire while flapping about or perhaps a rodent had entered the cage through the chicken-wire feeding hole and they had had some altercation. At any rate the joint became even more swollen and inflamed over the ensuing days.

We had some avian tetracycline on hand which we put in his water and even down his throat with a spoon, but it didn't improve the situation. We finally decided to ring a few vets to see if we could get some help.

Liz Hall-Downs: This took more than a few phone calls as many of the vets we approached wouldn't see Harry because he was a currawong. This surprised me, as they generally will treat injured wildlife for free. But currawongs have a bad reputation.

|

They are rumoured to steal the eggs and fledglings of smaller birds from their nests - though we personally have seen no evidence of this. The view of pied currawongs as 'Wolves with Wings' has been challenged by Ravenswood, who writes, "For some reason urban folklore has it that Currawongs drive away many other birds and hog territory for themselves. This really is folklore ..." Bayly and Blumstein's results on currawong predation and the decline of native birds suggest that "predation is greatest on introduced/ common species and less than expected on native/common species". |

[Above] King Parrot (Photo by Liz Hall-Downs, 2003)

They write, "It is difficult to separate the effects of predation ... from the effects of gross habitat change" and "While there is convincing evidence that currawongs are involved in the spread of weeds, ... evidence for their role in the decline of native bushbirds on both urban and rural areas is less clear … In our experience, the debate on currawong control is a highly political issue." (P.2) It may be true that those who travel in flocks in highly urbanised areas behave differently to those we encounter here at 'Euphoria', in a more natural ecosystem. Suffice to say that the only 'egg stealers' we've observed in three spring seasons at 'Euphoria' was the 5 ft Lace Monitor who took Harry's older siblings in 2001, leaving his mother to wail her sad and plaintive song for several days afterwards.

Eventually we found a sympathetic vet, who suggested we continue to give Harry oral tetracycline by eye-dropper. The leg, however, didn't improve, and we were concerned that he would be unable to fend for himself and have to be kept as a pet. Though we were prepared to keep him, we ideally wanted him to recover and leave us. So we returned to the vet and were given a five-day course of antibiotic injections to administer. Harry hated the injections, but the swelling started to go down immediately, and he slowly stopped doing what could only be described as 'crying'.

Kim Downs: Harry's leg had stabilised, and he was as keen as ever to be let loose. In every other way he seemed fit and strong enough, so we decided to give him some freedom and see how he went. I hung the small portable cage I had been getting him used to on our front verandah and one morning opened the door for him. He flew into a nearby tree and roosted there for several hours. We could see him limping and flapping his way around the tree, chasing insects at times. After several hours he flew back for a feed from his bowl, which was still in the cage. This method worked well. For the next few days I caged him in at night and let him roam during the day. He never went far and usually hung out in the same large stringy-bark, some twenty metres from the house. Once we had seen the vet and begun the series of injections, I was concerned that he might not come back one morning before we could finish the full course - as he didn't like getting the injections which were administered straight from the fridge directly into his breast muscle. But he kept coming back and wore the injections like a trooper.

[Above] Kim Feeding Harry (Photo by Liz Hall-Downs, 2003)

By this stage we had been letting him loose in the house for small periods over several weeks. He liked to come in and sit on the exposed roof trusses and ceiling battens. He was interested in our pet parrots and would roost as close to them as possible to sleep if given the opportunity. He would also bring himself down to the bed and lie down. If you reached over to him he wanted to play-fight. He would grab a finger with his beak and roll over on his side or back. He wanted to wrestle in the exact same way that puppies and kittens wrestle. After some fifteen minutes he would tire of the game and take himself just out of reach to the base of the bed. Here he would squat down and lie on his feet with his head stretched out in front of him and go to sleep. This exact pattern was played out almost daily for six to eight weeks.

Do animals enjoy play? Feel 'love'? Or is all this simple anthropomorphism? Our experiences with animals convince us that they learn and form relationships with many species within their environments, humans included, and that these can be positive and life-affirming if approached with care. Harry left us around March 2003. He gradually came in to the verandah to eat less and less frequently, until we were only seeing him every third day. Then, one day, he reverted to his old ways, hanging around the window then coming in to cuddle and play on the bed. It was last time we saw him for some time, and we often subsequently wondered how he was and whether he was surviving okay.

Seven months later, in October 2003, we were surprised to see a large currawong with a gammy leg, bald like his father, hopping on our verandah. Harry was back, and had brought a mate. We knew it was him because, besides the limp, he hopped up on the table and started banging spoons around, one of his old attention-getting ploys. At the time of writing (late November, 03), Harry and 'Harriet' have three healthy fledglings who are making great progress with their flight lessons.

These kinds of activities are time and energy-consuming and, along with the process of owner-building, have significantly influenced our creative output over the past few years. Individual studios are part of the housing plan. We hope to be able to settle into new and productive work routines once the building phase is finished. In the meantime, the odd sculpture or poem emerges, but not at the rate we'd like.

[Above] Home Among the gum trees "Euphoria" (Photo by Liz Hall-Downs, 2002)

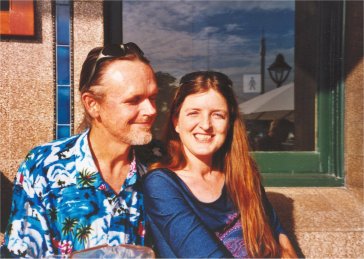

This 'time out', however, has been a valuable period of reassessing our lives and aims as creative artists, away from the frenetic pace of city life and the faddishness of public approbation. A new life like Harry's requires long periods of time and nurture to reach self-sufficiency and independence. Similarly, I believe good art also requires such time and nurture - periods of silence and inner contemplation help original ideas to surface and become manifest. Living in the middle of a varied and balanced ecosystem where our lives intersect daily with the natural world reinforces to us that this, rather than an obsession with material goods or 'success', is what provides meaning, connectedness, and lasting inspiration.

References:

Australian Museum, 2003, Pied Currawong, Factsheets (downloaded 26/11/03)

Bayly, Karen L. & Blumstein, Daniel T. "Pied Currawongs and the decline of native birds"

(abstract) (downloaded 26/11/03)

Currawong - Wikipedia, (downloaded 26/11/03)

Personal Property Assessment, Land for Wildlife, November 2000

Pizzey,G. and Knight, F. 1997. Field Guide to the Birds of Australia, Angus & Robertson, Sydney.

Ravenswood, Rodney, 1998, "In Defence of Pied Currawongs"

'Encountering Wildlife Without Feeding', Land for Wildlife, Note 20, April 2003.

About the Writers Liz Hall-Downs and Kim Downs

|

Liz Hall-Downs has been active in Australian poetry circles for 20 years. Her writing activities have expanded in recent years to include producing articles on Australian literature and the environment, and working in the community arts sector. Kim Downs is a writer, musician, and sculptor. His novel Jippi, was published by Papyrus Publishing in 2000. Liz and Kim's collaborative poetry and music show on gender issues, Fit of Passion, toured Australia and the USA in the 1990s, and was released in book and audio formats. Since 2000, they have been living at 'Euphoria', their idea of paradise in QLD. |

[Above] Photo of Liz Hall-Downs and Kim Downs by photographer unknown, 2004.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.8 (September, 2003) |