THE SUBLIME JOURNEY

By Jenni Mitchell

[Above] Messenger of the Ice (Oil On Canvas diptych 122cm x 304cm) (Artwork by Jenni Mitchell, 2003)

Antarctica and the South Pole. These words reach into our minds and conjure images of heroic survival, tragic death, modern history and exquisite beauty. Antarctica is a mystery and for most of us, as unreachable as the stars.

With a limited experience of Antarctica, gleaned from books, photographs and documentaries, my Antarctic imaginings were made up of an environment shrouded in hazardous blizzard conditions with low light and poor visibility. Antarctica was a forgotten place at the bottom of the world, inhabited only by a few species of penguin and seals. I had never thought of Antarctica as a place I would one day visit. Nor had I envisaged how important a sea journey could become.

Then my opportunity to visit Antarctica came in December 2002 when I was awarded a humanities berth from the Australian Antarctic Division on an ice strengthened ship to sail as a round-tripper to Casey Station. The ship, MV Polar Bird, was commissioned to re-supply the station with its annual supply of food, fuel, equipment, transport and personnel.

The nine day sea journey from continent to continent, Hobart to Casey, across the planet's wildest seas, and the nine day return journey was a voyage of a lifetime. I saw the sea in every conceivable state from mirror reflection calm to tumultuous water taller than the ship smashing across the bow. I watched the full moon's silver veil sparkle like glitter on the dark sea and the next night, sketched an apricot moon embedded in a pale mauve sky. I experienced a myriad of emotions and found a never-ending stimulus for painting and photography.

[Above Left] Ice Plateau, Outside Casey Station (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2002) [Above Right] Jenni Standing on Salt Crust. (Photo by Mervyn Hannan, 2002)

* * * *

Lake Eyre and Antarctica are technically both deserts. Visually, their features are similar in many ways. As well as the vast flat plains of ice, salt and sand, these deserts have parallel appearances in their worn mountain ranges sculptured by time and violent winds; there are flat topped gypsum mesas inland that appear like desert ice-bergs, carved also by time and extreme weather conditions. It is easy to mistake a winter's morning at Lake Eyre for Antarctica when the temperature plummets below zero and ice winds cut into exposed flesh with knife edge precision; the drinking water is frozen and the salt crust is firm enough for skating.

You can feel the rhythm of the sea in the flat hinterland surrounding Lake Eyre. When the sun heats the earth, the shimmer sparkles in the same way as the sun tips the ocean waves. The unceasing low sound of wind waves across the land and the lake surface seem also to mimic the musical rhythm of the sea.

Something takes over. There is an 'otherness' when alone in these simple environments. It is as if your essential being becomes united with the land; you are drawn into a deep inner place, a silence. This is the feeling, or 'place', which for some people, conjures fear of isolation. I find it exciting. To be in a wild environment of enormous horizons, surrounded by one element, salt, water, sea, ice, somehow places a perspective on our size and importance in the world.

[Above] Salt Lace - Lake Eyre (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2002)

My journey began in 2000. I was staying in the Tasmanian Writers' cottage in Hobart painting Tasmanian poets' portraits in my series of 100 Australian Poets' portraits (Adrian Lawrence, Sarah Day, Stephen Edgar, Margaret Scott, Phillip Mead) Between sittings I would walk along the wharf. One morning, docked and glowing against a backdrop of the deepest cobalt sky, lay an enormous red ship. The paint-work shone with a fiery brilliance and appeared to melt into the water. The colour spread around and beneath the ship in ripples of red and green. Mesmerized? Seduced? I knew then, I would take a journey on a vessel like this. Every surface of the ship was painted the same red, including the deck and bridge. The ice-breaker ship, Aurora Australis, was in dock for the winter, awaiting the summer season's work of ferrying personnel and cargo from Hobart to the many Australian bases and Islands spread around the Antarctic.

[Above] Polar Bird, Macquarie Wharf Hobart (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2003)

Two years later, as a recipient of the Australian Antarctic Division's Humanities fellowship I set sail from Hobart as artist-in-residence aboard a different ship, the ice-strengthened ship, MV Polar Bird. The summer of 2002-3 was significant for the Polar Bird as it was it last season of charter to the AAD. Polar Bird was built in Germany in 1984 for charter to the AAD. I began to hear a lot of jokes from Antarctic people about the poor old Polar Bird and how it was prone to being beset, or stuck in the ice, and the Aurora Australis would be sent to the rescue. The difference being the AA is an ice-breaker - purpose built to travel through ice, whereas the Polar Bird has been ice-strengthened only and lacks the power to work its way through the consolidated pack ice. Polar Bird has a large cargo carrying capacity whereas the Aurora Australis has little. Both ships have been of valuable service to the Australian Antarctic programme.

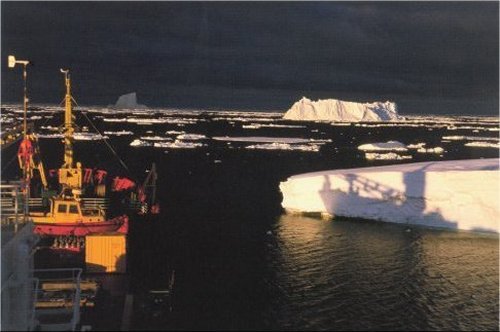

[Above] Polar Bird & Ice Shadow (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2003)

* * * *

The journey to Antarctica was for three weeks and most of that time would be spent on the sea. I could only imagine how to work on the ship and later, the shore. I had no idea how my materials would behave in the icy cold of the Antarctic. I knew from experience what to expect from my materials in the desert heat. I placed my paints in plastic bags inside the freezer for a few hours to a couple of days to test them. The acrylic paints and watercolours froze. The oil paints stiffened, but were generally unaffected; and the oil pastels improved their handling, sliding sensuously across the paper without any drag. To create a portable studio I used a large suitcase and bought a backpack for the camera equipment and tripod. (I didn't use the tripod at all - not much need on a moving ship or in the brilliance of the Antarctic ice and sunlight.) Instead of taking loose rag papers that I suspected may fly away on the strong sea and Antarctic winds, I cut and bound the papers into several sketch books. Using firm covers this eliminated the need to cart extra drawing boards around. I decided, after much deliberation to take my oil paints along with the turpentine and other high scent materials. I had concerns about the smell of turpentine and dammar varnish throughout the ship and how this may affect my fellow expeditioners. In the end, art won. I could not bear to be inspired by a particular subject that may cry out to be painted in oil and not have the materials nearby.

* * * *

February, 2002, before setting sail for the Antarctic, I took a twelve hour tourist flight from Sydney to Antarctica. At first, I was sceptical as to how much value this flight would really be, how much can you can see from the small window of a jumbo jet and whether it would really be worth it. Pleasantly surprised, I would recommend it and take it again. Four hours from Sydney to the ice continent, four hours flying over the ice and four back to Sydney. The flight above the ice from 10,000 feet was more spectacular than I could have imaged. With the clarity of a pristine atmosphere visibility was excellent. The pilot, an Antarctic enthusiast, made figure eight loops over the ice landscape so the 300 passengers could each have a good view of particular features. This was my first sighting of the ice continent. There was much excitement when the first iceberg was seen. There it was, a small white floating mountain drifting in a sea of Prussian blue. Beneath the iceberg was a skirt of crystal turquoise. As we were reminded, eight tenths of the size of the berg is beneath the surface, and shows as a shadow of the prettiest light. The flight was unreal in that we were witnessing from the comfort of a jumbo jet the largest, coldest, driest desert continent, where seventy percent of the earth's fresh water is locked up in the ice.

[Above] First Ice berg (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2002)

We flew over Casey Station, the nearest Antarctic Base to Australia and had a radio conversation with the Station Leader, John Rich. Our plane was the first visual contact the station had had with the outside world for twelve months and it was just as exciting for them to see a plane as it was for us to see an Antarctic base. From the warmth of the inside of the plane it was hard to believe the outside temperature was minus eight - a warm Antarctic summer day.

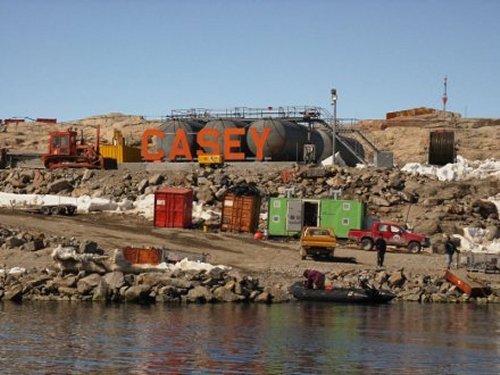

[Above] Casey Station (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2002)

From the air, I began to have mixed feelings about my association with salt and ice. Having flown over Lake Eyre in a small plane several times, I wanted to say, 'eat your heart out, Lake Eyre'. Although the ice and coast from the air appeared incomprehensible in breadth, there was still something similar in experience to flying over the flood or salt crust of Lake Eyre. Perhaps it is to do with the extreme remoteness and desolation of both places, or the continuum of the whiteness with the undulating subtle changes in colour and texture - the feeling of insignificance, of being human against the largeness of nature.

Always, with Antarctica, and to a lesser extent Lake Eyre, a sense of scale is elusive. Over Antarctica from a jumbo jet at ten thousand feet, or from a four-seater plane at ten feet above the surface of the dry lake there is little to visually gauge size and space. Are we observing a deep crevasse, a cliff or merely a break in the ice? Is the salt a chasm or an ant hill?

By using the language of paint and photography to record the landscape, it has to be read subjectively for its own sublimity and simple beauty.

[Above Left] Hagglund (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2002)

The Preparation

Preparing for any journey where I will be painting and using my camera requires much planning and writing of lists. Even for a painting trip to the desert I compile lists of all the possible things I will need to take and as I am usually travelling by car I am able to think in terms of more rather than less. Nothing worse than being in the desert and running out of cadmium yellow… I am mostly able to visualize the work I intend to make. I cut canvas to envisioned work sizes and roll them up to later re-stretch in the field. I make sure I have enough film and sunscreen and water.

After passing extensive medical tests and feeling I had confidently packed everything, (more than needed), I left Melbourne for Hobart to board the ship. The first night of the voyage began on the luxurious ferry, The Spirit of Tasmania. As the Victorian coast faded and the night fell over the sea, I began to imagine what may be ahead. The weeks of preparation were over. The gentle movement of the ship was soothing. Between pangs of disbelief and the excitement of being at sea, albeit on a ferry, purpose built with stabilizers to minimize passenger discomfort and a choice of excellent restaurants, I wondered what a working cargo ship would be like, without stabilizers and heading for the world's roughest seas. Much of the night crossing I spent on the cold windblown stern of the Spirit of Tasmania, riding the black waves and trying to imagine how much colder life would become.

[Above] Ariel Bergs (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2002)

Sailing day. That morning, the 79 expeditioners met at the AAD headquarters for a pep talk and a series of lectures to warn us of the dangers of risk taking. The Division's long time doctor, Peter Gormley, showed graphic images of injured expeditioners, including one with an ice-pick through his leg. People die in Antarctica. It is easy to become complacent and put oneself in danger. We are told always to carry our Survival book and survival pack, to go where we say we are going when away from Station limits and if we change our minds, we must return to the station first and register the new direction. Issued with name tags we are instructed to wear them at ALL times, never assume anyone knows who we are. We may need to be identified quickly. We have been photographed and our records kept at head office. The talk is heavy, the room quiet with concentrated listening and some of us wonder if we are crazy.

* * * *

[Above] Spray across Polar Bird Bow (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2002)

The Voyage

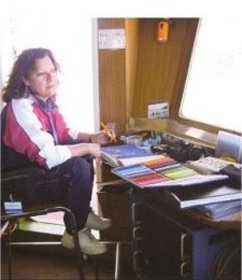

Each day, from my bridge studio, I watched the moods of the ocean and made pencil, watercolour, gouache and pastel drawings in the sketch books. For once, I had plenty of time to absorb my environment and I was able to spend hours studying the patterns and colours that made up the waves. I studied the horizon where the sky met the sea; sometimes a sharp line and at other times soft and blurred.

[Above] Jenni on Bridge Deck Polar Bird with Ice berg (Photo by photographer unknown, 2002)

After a week at sea I began to think we were on some kind of strange, endless journey across the oceans, and there was no ice. It was as if we were caught in another dimension, it didn't seem real. Then one bleak evening, when visibility was low and the ship was surrounded by fog, the captain announced the radar was showing icebergs in our range. Straining my eyes through the grey mist, I could just make out the blurred solid image of a light irregular shape in the distance: my first iceberg.

[Above] Ice-berg, Southern Ocean (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2002)

When the fog lifted from the sea a bank of bluish grey cloud became visible on the horizon. The cloud had a soft white underbelly. This is known as the 'ice blink' - an indicator of approaching sea ice. It is a chilling and wondrous sight. The next day engulfed in a sea of lumpy beaten egg whiteness, we sailed into the forever ice world of Antarctica.

The weight of the ice becalmed the turbulent sea, the white capped waves had ceased and the ice rose and fell with the rhythm of the ocean swell. The ship cut a swathe through the ice, leaving a dark trail of black water behind the stern. From the bow of the ship you could hear the silence and listen to the creaks and groans as the ship cast aside lumps of ice and made deep cracks across the pristine thick white sheets. Larger pieces rumbled and stirred the water as they rolled in the sea pushed by the weight of the ice-strengthened hull.

[Above] 'Frozen Sea' (Pastel on Rag paper) (Artwork by Jenni Mitchell, 2002)

From my bridge studio I draw in pastel and watercolour the ship's bright red bow against the gleaming ice. There is vibrancy in the contrast of the colours. An eerie blue light emanates from within the sculptural ice forms. It is as if an electric light has been turned on inside the iceberg, projecting the light into the day. There are numerous shades of blue from the subtlest: turquoise, cobalt, Kings blue to mauve and violet light. It is an exquisite vision to peer into an ice cave carved into the side of an iceberg and experience the magical blue rays.

[Above] Newcomb Bay (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2002)

Sailing into Newcomb Bay towards Casey Station was visually stunning. The water was the colour of and as flat as a facet of smoky quartz - the wake barely produced a ripple and the icebergs appeared to float above the water as they reflected into the silver sea. A cold mist rose from the tops of the icebergs creating an unearthly vision. Everything was silvery, the sky, sea and bergs. Soon, the buildings of Casey Station were visible and stood out as bold lego blocks of red, green, blue and yellow against the whiteness of the landscape.

[Above] Welcome to Casey Station (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2002)

Casey Station

While the fuel line and first unloading operations got underway we had to remain on the ship. This was an opportunity to bring out my oil paints and make my first paintings of Casey Station from the bridge deck. Working outside was a challenge after the comfortable warmth of the bridge. I needed to wear gloves, woolly hat and plenty of warm clothing. The wind chill was extreme, even though the temperature was a mild -1 degree. There were other difficulties too. Using rag paper I taped a sheet to a board with masking tape and proceeded to mix my medium from linseed oil, turpentine and dammar varnish. Everything began OK, and then I noticed the masking tape forming bubbles and lifting, and the medium began to drag and separate. I had never experienced this before; the cold appeared to affect the materials. I had to regularly bring the palette and painting inside to the bridge to warm sufficiently so I could continue working. Also, the ship kept slowly swinging on its anchor. I began my painting looking towards the buildings on Casey Station and a little while later; I would find I was looking in the opposite direction. I would have time to warm my materials and myself, or make a coffee before the ship decided to silently drift back into position.

All the while I was painting there was frantic activity in the bay. We were a kilometre from shore. The fuel line was slowly reeled out to the shore by men in zodiac boats. They needed to be careful to keep the line out of the way of loose rough pieces of ice which could cut the line and cause an environmental disaster. It took a team of trained expeditioners many hours to stabilize the line. This operation is one of the most important and delicate jobs; fuel the life blood and source of power to keep the station working for the next year. Wind turbines are under construction and the expected source of power for the future. A relay of barges also began to take cargo across to the shore. Containers were lowered expertly from the ship; hundreds were to be unloaded during the next week with everything for the next year from frozen food, fresh food, medical supplies, stationery and tools.

Coming to terms with the 24 hours of daylight was a challenge. The days had been lengthening continually since leaving Hobart as we headed south. By the time we reached Casey there was barely a twilight. It was strange going to bed during the day. I would get up and go up to the bridge at any time. I remember one night being startled awake by a noise and going upstairs to the bridge; there was the most stunning cool gold glow across a sea with the merest hint of ripples. I was not alone. Other expeditioners had been aroused from sleep and were also experiencing the sensational view.

[Above Left] Jenni at Bridge desk studio (Photographer unknown, 2002) [Above Right] Studio with Antarctic paintings (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2002)

I had only a week to get a brief glimpse of life on an Antarctic Station and to visit the various changing environments. Several 'jollies' (the Antarctic term for trips away from stations, days out ... tours) were organised. To get around and away from the station several modes of transport are used: Zodiacs mostly around the bay and Hagglunds, or quad bikes away from the station to traverse the ice.

In a convoy of three zodiacs we toured the cliffs and wild rock and ice coastline through the Windmill Islands. With trained pilots we skimmed at a great pace across the Antarctic waters, rugged up in waterproof ventiles and loaded down with survival equipment. We had ice picks and bags to crawl in if we became stranded on the ice. Continually, we kept in radio contact with the station. It was easy to forget this was not any sunny day on the bay. Antarctic weather changes quickly and dangerously and a clear sky can soon change to a frightening disorientating blizzard.

The ice cliffs were the most beautiful and extraordinary formations I have ever seen. There were a myriad of shapes and forms. Cliffs appeared as; precision machine perfect lines, others as mountainous, wild free-form sculptures, organic molten shapes; there were ice caves with blue light emanating from within their void, crevasses opening from broken glacial blocks spilling into the sea. There were rock penguin breeding colonies, slug-like seals lolling about on the sea ice, and the snow petrels high above the cliffs, elegant white dots, butterfly-like above the sea.

We ate our packed lunch, on an ice beach alongside seals and groups of Adélie penguins. It could have been a beach scene anywhere. The sun was brilliant and reflecting painfully from the ice. The small bits of our faces that were exposed were burning. Penguins came up to us, as inquisitive as we were of them. Photographs and documentaries can never capture the iridescent shimmer and brilliance of their white breast feathers. They shine with the intensity of the light of the eye in a male peacock's tail.

[Above] Lunch on Ice (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2002)

We had been warned to keep away from the cracks in the ice; they are breaks in the ice to the sea. I had wanted to photograph a pond nearby, attracted to its bright turquoise water. As I neared the pond, of course down I went into the water, through the ice. I had not thought of the bottom as being the gateway to the sea ... I climbed back onto the solid ice and stood up and down I went again. It was not easy for my fellow expeditioners to come to my assistance, because they too would have gone down into the water. Somehow, I remained calm and was surprised how quickly I 'thought' myself light and crawled onto the ice and away from the menacing hole.

Another spectacular journey was to the ice dome, several kilometres away from the noise of the station generators. This trip was taken in one of the Hagglunds, the heavy slow, low geared and noisy vehicles designed to go anywhere on the ice and snow, even to float and drive themselves out of crevasses. Out on the ice plateau I had the sensation I had been searching for when seeking the similarities to the salt crust of Lake Eyre. Here, forever, was a horizon of whiteness beneath the cold blue sky. The road to the dome was marked by a series of tall cane lines protruding out of steel drums. On a good day, they were readily seen and easily followed. During a blizzard, when visibility is non existent, they are tracked by Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite instruments installed in the vehicles. Beer cans have been placed on top of the canes for navigation. We did not reach the top of the dome, the slow hill continued to climb for another 150 kilometres, several days by Hagglunds' speed.

Homeward

All too soon the season's station change-over was completed. New supplies were stacked in sheds, fuel unloaded and the changing of the Station Leader ritual was over. This is a big day. There are many speeches and tearful partings. The key to the station is presented to the incoming leader, the outgoing leader is presented with a memento - a framed ice-pick.

Expeditioners who have spent a year in this small cocoon of an environment have to begin the mental transition of returning to a 'normal' society. Even for the short time we have been at the station friendships have been made and partings have been meaningful. The Australian bases have good feelings. Perhaps, due to the tradition of everyone being equal; whether you are the station leader, scientist or mechanic; you do your regular rostered shift as slushy (kitchen hand) and stores (packing and unpacking). There is a roster for cleaning the bathrooms, floors, and everybody does it. Surprising also was how quickly you 'tuned' into life on ice. 'Home' was a long way away.

Rather than being homesick, I became more saddened by the idea of returning 'home'. There was something compelling about Antarctica and the idea of being in such a pure environment; everything so bright, clean. I will never be the same again. I am 'ice-affected'. For the first period of being home I noticed all of the dust around the place. Even the earth and grass appeared contaminated. It was as if I had come from another planet.

[Above] Penguin Berg (Photo by Jenni Mitchell, 2002)

Landscape is a personal thing. Antarctica and Lake Eyre stimulate a spiritual place inside of me. I think we all have our special places and they are probably different for each of us. Through my painting, writing and photography, I am still trying to come to terms and understand where I have been. My experience of Antarctica is just the beginning and I intend to return, for like working in Lake Eyre, one trip is not enough to gain any depth of understanding. I will continue to visit and research Lake Eyre and Antarctica through my work until I have reached a point where I feel I can move on. What Antarctica has shown me is just the merest hint of visual opportunities.

I am indebted to the Australian Antarctic Division for the berth on their re-supply ship, the MV Polar Bird. I am also indebted to the crew of the Polar Bird for their generosity and support in allowing me to set up a studio to work beside them on the bridge. Without this opportunity, working in the confined quarters of a shared cabin would have been extremely difficult.

It was enlightening to be on the bridge beside the scientists conducting the wildlife count and to realise the sightings of whales was down on expectations. For whatever reason this may be, it is an indication of the environment being out of balance. The first explorers reported whales and albatross in such abundance the seas were literally deep in ocean wild-life - on this trip, a whale sighting was rare and cause for great excitement.

Antarctica is the last great wildernesses on the earth and it is essential it is looked after by the international communitys and respected for its fragility and purity - for our understanding and for the future generations of our planet.

Several photographs from this feature have previously appeared in To The Ice (Line Pubications, 2003). This research trip was assisted through funding from The Australian Antarctic Division.

About the Writer Jenni Mitchell

|

Jenni Mitchell is best known as a painter of the Australian landscape and of Australian poets' portraits. She is currently undertaking a Masters of Visual Art at Monash University in Victoria and is researching the visual similarities of the extreme desert landscapes of Lake Eyre and Antarctica. Jenni Mitchell travelled to Antarctica in 2002/03 as the Artist-In-Residence for the Australian Antarctic Division. Jenni Mitchell has had more than 40 solo exhibitions throughout Australia, and has been included in many group exhibitions. Her works are represented in public and private collections in Australia, USA, UK and Japan. |

[Above] Jenni Mitchell painting from Polar Bird bridge deck with Casey Station in background (Photo by photographer unknown, 2002)

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.8 (September, 2003) |