GUEST EDITORIAL

By Susan Hawthorne

Thylacinus cynocephalus - "The pouched dog with the wolf's head".

Welcome to the eighth issue of Thylazine: The Australian Journal of Arts, Ethics & Literature.

Synchronicity is the lifeblood of poetry. It creates moments which rattle inside one's head, make you sit up and take notice or the extraordinary in the ordinary.

The synchronicity I am talking about is the phrase the body in pain. It happens to be the title of an essay in Thylazine, issue 7, but also the title of a book by Elaine Scarry I am reading, and it connects with an area of performance and research that is engaging me right now.

The book The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World is a dense and insightful book. My copy is now filled with underlinings, with comments, with the beginnings of essays or poems. Elaine Scarry's approach is a bit like the poet's. She writes a sentence and over the next several pages unpacks the sentence, teases out all the possible threads of meaning. She engages with the hypothesis that "Pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it". (1985: p. 4)

The problem of pain is an enduring one. How can anyone else know that another person is experiencing pain? Against this is the utter immediacy and overwhelming knowledge claims of the person suffering pain. There is no escape from it. It is undeniable. Its existence unquestionable.

Scarry pushes the analysis through a consideration of the structure of torture - pain in an extreme individualised form - and the structure of war - pain and injury as a hugely collective experience. These are things that are escalating in importance day by day. Daily, the world reels with violence at the level of the domestic, the home front as well as at the global, the international, the frontline of war between nations and peoples (see Hawthorne 2003a)

What happens in the relationship between the torturer and the tortured is a series of denials and reversals that ensure that the torturer not only maintains his power, but builds upon it, amplifies and extends it while simultaneously it is the tortured person who takes the blame when the result is a confession, what Scarry calls a "betrayal of the self".

|

Of course, the tortured person has lost everything. S/he has nothing left except perhaps a voice to scream with (if s/he has not been so mutilated as to take this away too), or a hand to sign what is by then an insignificant document eroded of meaning because as Scarry argues, it is not information that the torturer is after, it is power. The answer to the torturer's question is less important than that the person answers. Withholding an answer angers the torturer most. Silence is the tortured person's only avenue of power. When torture is discovered, as it is after wars, or when Amnesty International issues a report, it is denied. |

[Above] The Pain of Versai, France (Photo by Coral Hull, 2002)

No one brags about being a torturer. Denial of torture is the norm. The torturer can claim that he did not know that the person was in pain. And in an epistemological sense this might be so. But in the real world we do recognise when someone is in pain - and the torturer cannot deny attempting to create pain, for why bother with all the tools of torture if they mean nothing on the pain dimension? Intent to inflict pain, therefore, is integral to the torturer's actions.

The Research

What impelled me to look into the subject of torture? It was the realisation that among those who are tortured there is one group who is almost always omitted from the lists. Lesbians. It is as Gillian Hanscombe writes in her long meditative poem Sybil: The Glide of Her Tongue:

No one is proud of dykes (not families not neighbours not friends not workmates not bosses not teachers not mentors not universities not literature societies not any nation not any ruler not any benefactor not any priest not any healer not any advocate). Only other dykes are proud of dykes (Hanscombe: p7)

But when it comes to torture, if no one is proud of lesbians, and no one other than lesbians is prepared to speak out about the torture, what we have is a deafening silence.

|

Even Amnesty International admits that it is difficult to press for torture of lesbians to stop because simply mentioning the names of those who have been tortured might put them in further danger. That is, by campaigning on behalf of lesbians, there is a genuine fear of reprisal and further violence. Another clue lies in the following statement from a Peruvian lesbian:

When I speak of my right to my own culture and language as an indigenous woman, everyone agrees to my self-determination. But when I speak of my other identity, my lesbian identity, my right to love, to determine my own sexuality, no one wants to listen (ILIS Newsletter 1994: p3) |

[Above] The Pain of Versai No.2, France (Photo by Coral Hull, 2002)

It is this distancing of political support from others, who may well deem themselves progressive, that is a feature of lesbian existence. Lesbians have supported, fought for, with and alongside a host of other people for political rights, but when on the rare occasions lesbians ask for support we find that the support is often absent. Such reactions have been evident in the recent announcement by Australia's Uniting Church to officially allow out lesbian and gay ministers. It has been extraordinary to watch ordinary people who in the main regard themselves as ethical come out with intensely hate-filled sentences. Views most would probably not express if it were an issue of race or culture or ethnicity or religion (to be sure, some would express such views).

There are some interesting parallels between the silences around torture and the silences around lesbian existence. Denial remains an important political response to both. To speak of torture is not done. To speak of lesbians in ordinary and positive ways (or in ordinary and critical ways) is also not done. Both states of being have a tendency to be exoticised, to be distanced from daily life. And yet, of course, lesbians and those who have suffered torture live daily lives just like anyone else.

As Elaine Scarry argues torture unmakes the world through the infliction of pain. For an individual who belongs to a despised group - as do lesbians in countries where they are tortured - the unmaking, the unravelling of the world is already partially in place through a double or sometimes multiple silencing. The dismantled world of the tortured lesbian is an extreme position. It is severe in all the senses of deprivation and psychic impoverishment implied by severity.

References

|

Melissa Ashley. 2003. "The Body in Pain: Depictions of Suffering in the Poetry of Jordie Albiston and Coral Hull. Thylazine, Issue 7.

Gillian Hanscombe. 1992. Sybil: The Glide of Her Tongue. Melbourne: Spinifex Press.

Susan Hawthorne. 2003a. "Responsibility: Personal and Global." Altitude. Vol.1, No.1. http://www.api-network.com/cgi-bin/page?altitude21c/issue_3

Susan Hawthorne. 2003b. Text extracts from drafts of Elisabetta's Story. Performed as part of Something Old, Something New. Performing Older Women's Circus, North Melbourne Town Hall, 11 September to 20 September and the ILIS Newsletter. 1994. Vol. 15, No. 2. p. 13.

Adrienne Rich. 1993. What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Poetics. New York: W.W. Norton. |

[Above] The Pain of Versai No.2, France (Photo by Coral Hull, 2002)

Consuelo Rivera-Fuentes and Lynda Birke. 2002. "Talking With/In Pain: Reflections on Bodies Under Torture". Women's Studies International Forum. Vol. 24, No. 6. pp. 653-668.

Elaine Scarry. 1985. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Susan Hawthorne (Guest Editorial)

The Thylazine Foundation thanks the following people for their generosity: John Kinsella ($50.00), Joyce Parkes ($80.00), Edwin Wilson ($25.00), Cameron Borg ($50.00), Aileen Kelly ($95.00), Les Murray ($40.00), Patty Mark ($50.00), Susan Kruss ($25.00), R L Philips ($85.00), Amber ($40.00), Anon ($15.00), Terry McArthur ($75.00) and The Literature Board of The Australia Council for The Arts ($2,500.00) towards towards the publication of Thylazine No.8 and The Thylazine Foundation's charitable works

A special thanks to the contributors and staff; Melissa Ashley, MML Bliss, Graham Catt, Jennifer Compton, Jack Drake, Kevin Gillam, Liz Hall-Downs, Susan Hawthorne, Richard Hillman, Coral Hull (that's me), Chris Mansell, Jenni Mitchell, Vera Newsom, Sharon Olinka, Joyce Parkes, Kerry Reed-Gilbert, Richard Ryan, Elaine Schwager, Thomas Shapcott, Malobi Sinha, Pamela Sidney, Andrew Taylor, Terry McArthur, Warrick Wynne and the many artists and photographers whose work is included in this issue.

And others; Inez Hull, Kindi and Binda who renew my dreams on a daily basis, the ten black angus cows from Rylstone in New South Wales, Australia who have survived the drought, Judith Beveridge, Thom The World Poet and all his friends in Texas who run The Poets Pantry, The Salvation Army in Palmerston, The Northern Territory, Harry the Currawong, and to Antarctica; including Charlie Rosenberg and the crew at The Institute for Global Communications (IGC) and The EnviroLink Network (San Francisco, USA) without whose assistance this website would not be possible.

Ammendments: Thylazine wishes to make amendments to Billy Marshall Stoneking's article Pi-0 An Appreciation that appeared in Thylazine No.5, September 2002. The excerpts of Pi0's visual poetry, which were cited as part of this critique, were meant to appear on the right hand side of the page rather than in the centre of the page. The person who took the photograph of the poet Pi0 is Sandy Caldow.

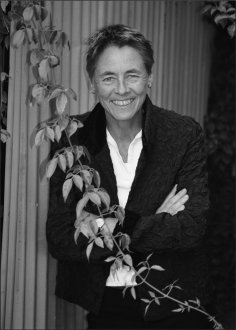

About the Writer Susan Hawthorne

|

Susan Hawthorne is a poet, novelist, academic and circus performer. Her books include a collection of poems, Bird (1999), a novel, The Falling Women (1992/2003), Wild Politics: Feminism, Globalisation and Bio/diversity (2002) based on her PhD as well as numerous anthologies, the latest of which are September 11, 2001: Feminist Perspectives (2002, co-edited with Bronwyn Winter) and Cat Tales: The Meaning of Cats in Women's Lives (2003, co-edited with Jan Fook and Renate Klein). She is a founding member of the Performing Older Women's Circus, co-founder with Renate Klein of Spinifex Press and a Research Associate in the Department of Communication, Language and Cultural Studies at Victoria University, Melbourne. She has recently performed an aerials segment - Elisabetta's Story - as part of the annual Performing Older Women's Circus show at the North Melbourne Town Hall. |

[Above] Photo of Susan Hawthorne by NACED, 2003.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.8 (September, 2003) |