THE BODY IN PAIN:

DEPICTIONS OF SUFFERING IN THE POETRY OF JORDIE ALBISTON AND CORAL HULL

By Melissa Ashley

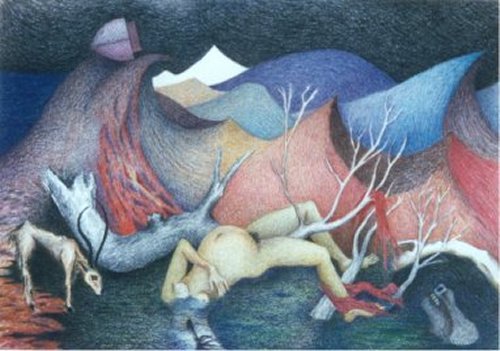

[Above] Not Wanted on the Voyage (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, 1993)

Introduction

In the essay "Someone Is Writing a Poem," Adrienne Rich observes that "[i]n a political culture of managed spectacles and passive spectators, poetry appears as a rift, a peculiar lapse, in the prevailing mode. The reading of a poem, a poetry reading, is not a spectacle, nor can it be passively received. It's an exchange of electrical currents through language" (83). This "electrical" exchange passes through the reader's body as a circulation of nervous excitement. There is a sense of anticipation and an uncanny recognition, initially beyond words, of what the poet has achieved in taking "that old, material utensil, language, found all about you, blank with familiarity, smeared with daily use, and mak[ing] it into something that means more than it says" (Rich 84).

During the 1990s many Australian women poets became interested in re-creating and re-inscribing a place where the repressed female body might speak. Coral Hull, Jordie Albiston, Alison Croggon, Rebecca Edwards, Judy Johnson, M.T.C. Cronin, Keri Glastonbury, and many others have expanded the boundaries of poetic language's transcendent or high aesthetic to let in the rhythms, rents, cries, silences, breaths, and fluids of the female body. Alicia Ostriker interprets North American women poets' "more frequent deployment of anatomical imagery" (than their male counterparts) as part of a complex cultural undertaking of reconsidering and reinterpreting the question of "what our bodies mean to us" (92).

For Hull and Albiston, the work of renegotiating the meaning of the female body is intricately tied to suffering. Exploitation, pain, illness, loss, trauma, oppression, violence, and self-destructive practices are recurrent themes in Hull's How Do Detectives Make Love? and Williams' Mongrels, as well as in Albiston's Nervous Arcs and Botany Bay Document. Deploying formal poetic strategies - Albiston's meticulous attention to line arrangement or Hull's subversive interpretation of the lyric - both poets also introduce devices related to écriture fèminine and postmodernism such as inter-and meta-textuality, mimesis, exaggeration, and repetition. The result is a corpus of poems that participates in the wider feminist undertaking of expanding the parameters of language and discourse to clear a space where the disquieting and, at times shocking and confronting, knowledges, cries, and resistances of the female body in pain may register and be heard.

Clearing My Name as Actress, Announcing Myself as Real: The Female Body and Sexual Harassment and Abuse

Sexual abuse is one of the most loaded issues our society will ever have to face, largely because it is tied to the history of gender roles. Although girls and women do perpetrate sexual abuse, the great majority of perpetrators are male; although boys and men are victimized, the majority of victims are female.Susan C. Wooley, "Sexual Abuse and Eating Disorders: The Concealed Debate" (174)

|

The issue of women's sexual exploitation, whether in the form of verbal harassment, the sexist subtext of billboards and television commercials advertising products like shoes and bras, or an individual's violent sexual assault and abuse at the hands of a specific perpetrator, is a recurrent motif in Hull's and Albiston's collections. As indicated in the epigraph, questions of sexual difference are directly related to the reasons that women on the whole, experience greater levels of sexual harassment, victimisation, and abuse than men.

Albiston's poem, "A Nice Afternoon," suggests that mass media representations of women's bodies as sexual objects affect the lived experiences and attitudes of real women and men. The poem is presented as the interior monologue of a woman walking along a city street one afternoon. The speaker's tone of ironic understatement elicits an empathic response in the reader, raising her awareness and sharpening her sensitivity to the ubiquitous and sometimes disturbing images of sexualised female bodies advertising commodities:

I am stepping with ease […]

Bracing my

self against swift bursts

of image and catcall I

stroll in safety past news-

stand advertisement (69) |

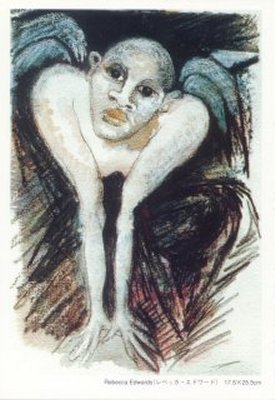

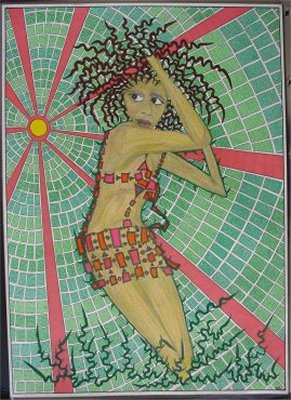

[Above] Dream of Flying (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, 2002)

The deliberately ambiguous phrase, "it's a nice afternoon," is central to the manner in which the poem produces meaning. In the first stanza, the speaker is "holding my / head high breathing it in" (69), however, as the narrative unfolds, Albiston's association of images of women's objectified bodies with the speaker's increasingly negative perceptual state, "women in bras on / fifty-foot screens … I am starting / to go cold … under pictures of violence … trying / not to cry" (70), accumulates, climaxing in a reversal of the phrase's original meaning:

I am strolling and trying

hard not to scream That's

Not Me On The Screen on

a nice afternoon. (70)

The billboards confronting the narrator as she walks along the street represent a host of familiar cultural discourses which over-determine women's sexual or reproductive roles and, in so doing, neglect, undermine, and efface other instances of their social and cultural agency. Albiston articulates with superb clarity precisely how the texts of the mass media and advertising redeploy an array of pre-existing masculinist myths surrounding women's bodies as sexually desirable objects, to speak a garbled message which elicits a response of desire and derision in certain men, and fists and teeth clenched-frustration in women:

they

want me to ride with them

high as the sky and pouting

like women in pictures they

buy. (70)

On several occasions Albiston's narrator mentions the time of day she is out walking - 3 o'clock - ironically acknowledging that even in the middle of the afternoon, in a public space, women can experience their freedom of movement restricted. In "Royal Park Stalker Sequence", Hull expresses a similar sentiment: "but senior constable I was only stalked in broad daylight" (92). Inherent in both poets' observations are undertones of annoyance and exasperation. They express resentment towards a social and cultural system that appears to remove the burden both of prevention of and responsibility for sexual harassment and violence from the shoulders of male perpetrators onto the bodies of female victims.

Throughout "A Nice Afternoon," the speaker's increasingly unpleasant encounters are depicted as embodied, for example, in the final stanza she is "cold and / alone strolling the path / quickly all the way home" (70). Alterations to her sense of self and mood register not just on the interior of her skin but externally, in her posture and quickened pace of movement. Although advertising can be innovative and entertaining, "A Nice Afternoon," shows how the frequent objectification of women's bodies can negatively affect the everyday experiences and self-perceptions of individual women.

[Above Left] Title Unknown (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, year unknown), [Above Right] The Wounded Healer (Mixed Media/paper 42cm x 57cm) (Artwork by Coral Hull, 1991)

Albiston's poem, "Susanna and the Elders," also examines visual sexual harassment, exploring the connections between masculinist depictions of an historical female character's sexual desirability and vulnerability, and a contemporary speaker's experiences of unwanted male attention. In the Notes section of Nervous Arcs, Albiston includes a brief outline of the Biblical story, "Susanna and the Elders". Two old men spy on Susanna while she is washing and together concoct a blackmail scheme designed to coerce the young woman into sexual relations with them. Susanna rejects the elders' threats, is accused of sexual misconduct, and sentenced to death. At the last moment she is reprieved because an insightful lawyer discovers inconsistencies in the elders' testimonies. Susanna's story has cultural resonance because her drama, particularly the event of the overbearing elders' threatening her - partly naked, young, and in a state of distress and fear - has been depicted many times, in canonical European art, for example. Albiston's intervention in the story re-frames artists like Rembrandt's, Tintoretto's, Reni's, Van Dyke's, and Lotto's voyeuristic foregrounding of the moment of Susanna's sexual and physical vulnerability to focus instead on the dénouement, in which she is vindicated.

The speaker, feeling threatened by the unsolicited male gazes of "the new elders crouched behind / cameras and car wheels" (71), addresses the fictional Susanna for advice. "You are difficult to / see through the foliage of / history" (71), she says, comparing the dense complexity of (art) history to a forest in which one might easily become lost. Throughout the poem, time folds back on itself, the distinctions between the present and the past merging together. The metaphor of cultivated and exotic gardens, "your / beauty filters through mastic / and holm leaf" (71), while on one level evoking the ancient scene of Susanna's harassment and blackmail, on another level, forges a link - beyond temporality and cultural difference - between the two women:

I am hid

beneath hard metallic bower

and kinetic sky in the synthetic

arbour to come. (71)

"Woman ought to rediscover herself ... through the images of herself already deposited in history," writes Luce Irigaray ("Sexual" 169). Sylvia Bovenschen makes the interesting point that "[t]hrough the centuries, culturally diverse standards of beauty have repeatedly re-established the status of the female body as object" (126). She continues, "one finds little difference between the depictions of the 'great artists,' which have become frozen as norms; and the trivial dictates of taste handed down by the culture industry" (128).

|

For Albiston, masculinist renderings of female bodies as sexual objects in art cannot be entirely veiled or swathed in an aesthetic of beauty, particularly given that the canonical depiction of Susanna as sexually desirable occurs with the threat of rape or death. The poet enters into conversation with these images, which leave Susanna no place in which to voice her own desires for privacy and quietude:

your two maids

absent your body in light as

you wash your fair limbs at

noon. (71)

The speaker's mention of the enveloping fluidity and formlessness of water, in depicting Susanna at her bath, hints at a female sensuality:

What is it you say as the

water encloses what words

do you have for your hereafter

sister [?] (71)

The poem ends on a hopeful note. Unlike the loneliness and frustration which plague the speaker at the close of "A Nice Afternoon", the speaker in "Susanna and the Elders" is inspired and strengthened by her imaginative interactions with the character Susanna. Susanna's eloquent and confident assertion of her right to privacy presents women with an empowering illustration of how to overcome unwanted sexual attention: "bring me the oil and washing balls / and shut the garden doors" (72). |

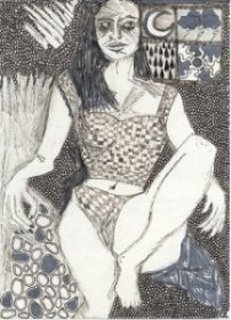

[Above] Title Unknown (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, year unknown)

Hull's prose poem, "Royal Park Stalker Sequence," is "deceptively accessible" (McLaren 222) in its interrogation and problematisation of stereotypes of feminine sexuality, demonstrating their underlying connections to violence against women. The poem's cumulative and cyclic narrative style, its unsettling of binary hierarchies, and its deployment of rhetorical techniques like repetition, exaggeration, and mimicry, can be understood via the Irigarayian idea that women can recover the eliding and repressing of their sexual specificity in discourse if they deliberately assume the feminine role (This 76). Through a process of resubmitting herself to masculinist ideas about who she is, she can make visible, "by an effect of playful repetition, what was supposed to remain invisible: the cover-up of a possible operation of the feminine in language" (This 76). Occasionally the speaker's tone becomes passionate, her imagery hyper-real. The 'disruptive excesses' of the feminine body in pain perforate the Symbolic boundaries of the text to turn the activity of reading into a disquieting, sometimes shocking, corporeal event:

his hammer hands smashing my teeth in / my crumbling teeth

like chalk/ & my broken open mouth that will never

close again/ I will cry out to the overhead leaves

rushing the sky with silence / with only the wind

through the feathers of birds to cover my nakedness/ (91)

The poem unfolds as a compelling description of a woman's increasing discomfort at being followed and threatened, during the day, in the public space of a park, by "derelicts" and "perverts." The speaker introduces the theme of sexual difference almost immediately, expressing a mixture of pity and contempt for the "ruined sexualities" of the stalkers "chasing you across the park with their / pink skin dangling from their pants" (86). Throughout "Royal Park Stalker Sequence," Hull depicts the subjectivity and lived experiences of both attacker and victim as embodied. One of the most effective ways in which she communicates feminine and masculine subject positions as embodied, as well as precariously marginalised, is by their close proximity to the abject. For Julia Kristeva "significance is indeed inherent in the human body" ("Powers" 237). The body's surfaces and orifices function to represent and to symbolise sites of cultural marginality, regions of social entry and exit sites of compromise and confrontation. The abject-the body's unassimilable waste products such as pus, sperm, blood, faeces, and vomit - when encountered elicit feelings of loathing, repugnance, and defilement.

It is not lack of cleanliness or health that causes abjection but what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules. The in-between, the ambiguous, the composite. (Kristeva, "Powers" 232)

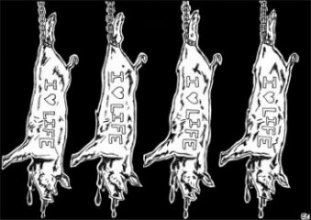

[Above] I Love Life (Marker/paper 21cm x 30cm) (Artwork by Coral Hull, 1991) [Above Right] Wounded (Charcoal/butchers paper 37cm x 56cm) (Artwork by Coral Hull, 1991)

Hull's depictions of the derelict-stalkers "tripping over / their own shoelaces or going for a gigantic tumble / into a puddle of vomit created by them for them to / fall into" (86), produces a double-edged meaning. The derelicts' publicly visible bodily fluids testify, on the one hand, to their economic and social marginalisation, yet on the other, they powerfully personify the extent of the threat to the female speaker's personal and bodily integrity posed by the event of sexual attack or rape.

The poem moves swiftly from a theme of pursuit to one of attack and abuse, mutilation and death. The speaker confronts her audience with the suffering bodies of women who have been violently assaulted and attacked:

the police […] while noticing

the details of my appearance & requiring physical

evidence/ whilst requiring my ripped shirt & semen

stained underpants / my dull black eye, splitting

headache & broken jaw (92)

The lists of incidences of women's sexual and physical violation borders on the surreal, dazing and occasionally overwhelming the reader. In some of the most disturbing lines of the poem, the speaker identifies herself with the mutilated body of a female murder victim:

requiring my slashed

nipples & tangled intestines to hang down over my cunt

requiring my corpse for less paperwork (92)

Cahill writes that rape and other forms of sexual violence are oppressive forms of "social sexing" which oppose women and men:

The fact that men can be but are not often, raped, emphasises the extent to which rape enforces a systematic (i.e., consistent, although not necessarily conscious), sexualised control of women." (45)

The poem's unflinching narrative exposes the violent underside of cultural and social processes which script male bodies as dominant and aggressive and female bodies as weak and passive, inscribing the "vagina [as a] place of emptiness and vulnerability, the penis as a weapon, and intercourse as a violation" (Cahill 45).

In part three, the narrator explores the various strategies she might use to communicate to her attacker that women are not objects but sentient human beings, made from flesh and blood, and capable of pain: "would you like a cup of tea? / & then you will see me as human / & the stalker will see me as human" (92-93). Albiston uses a comparable strategy in the poem "Lizzie's Pact," in her collection Botany Bay Document. Lizzie is a former convict woman working as a domestic servant who is raped by her employer following a night of dancing and fun. In "Lizzie's Pact," the speaker wonders how she might convey to her attacker Munroe, the extent of the injury he has caused her:

If I had a message

for young master Munroe

it would be it would be

a fistful of flowers a

wreath of my wrath a

litany of lilies sweet-

scented as blood to

bloom and bloom in his

favourite room for the

term of his natural life. (5)

The bouquet of flowers Lizzie would like to present Munroe with are explicitly connected to funerary rites and, following on from this, to imprisonment. In both poems, the social rituals of sharing meals and sending flowers are metaphors for the speakers' sense of a continuing relationship to their attackers. Although death and the desire for closure frame Lizzie's feelings about her rapist, Albiston's use of irony suggests that he continues to relate to her as a kind of haunting absent presence.

The speaker in Hull's poem on the other hand, sarcastically expresses a desire to seek out and befriend an abusive male and thereby prevent him from forcing her into a violent exchange: "I want to run / a bubble bath for men who bash their lovers" (93).

In the light of some of the other poems in the collection How Do Detectives Make Love? for example, "The Black Gun, "How Do Detectives Make Love?" and "Pornography II," whose speakers encounter problems in distinguishing their experiences of sexual or physical victimisation from their feelings of sympathy, desire, and identification with their attackers, it is possible to read parts of the poem within a broader, more complicated context. Although she has been bashed, assaulted, and left in the bushes, the speaker in "Royal Park Stalker Sequence" feels bonded to her abuser: "he is the stalker I am in love with" (91).

|

Section four, which consists of a fantasy scenario whereby the narrator obtains a gun and takes revenge on her attacker, can be compared to a well-known poem by Gig Ryan, "If I Had a Gun". In both cases the narrators reverse the roles of female victim and male aggressor to explore the fantasy, presented with a clever mix of black humour and rebellious rage, of undertaking physical retaliation. The poem's closing sequences, though, are bleak. In part five, the speaker's fragmented body:

my wisdom teeth

roll along the ground / like wheels of bone, like coins

among the dry leaves (99)

lies dead in the public park, awaiting its "final / absorption into grass" (99).

Hull's long poem, "The Statue" offers an unusual variation of the dramatic monologue. A female speaker ('i'), and an omnipotent narrator ('he'/'she'), alternately relay their versions of a sexual encounter between a woman and a man. |

[Above] Woman in the Thorns (Mixed Media/paper 42cm x 59cm) (Artwork by Coral Hull, 1989)

Hull's anti-realist device draws attention to the interior discursive activities of creating meaning from lived experiences, focusing in particular on the ways in which women and men respond to situations from differently positioned or socially and culturally scripted, points of view. As Irigaray writes, "woman's desire would not be expected to speak the same language as man's" (This 25).

Hull's use of language is fragmented and direct, mimicking interior thought processes and colloquial speech: "are you okay? are you okay? no answer. he moves closer towards her mouth. no answer" (18). Although the woman insists she is not interested in sexual activity, the man callously disregards her desires, and attempts to initiate sexual contact. The scenario is not unfamiliar in the light of Hull's frequent depictions of a predatory or violent male abusing or attacking a vulnerable female because of her 'insulting' unavailability and disinterest or simply for being in his spatial vicinity, as in the poems "The Compass," "Walk the Streets (Become Fierce)," and "A Misogynist Gives His Many Excuses". In "The Statue," however, Hull presents the female speaker as suffering from post-traumatic stress.

Seemingly aware of her boundaries the woman informs the man that she occasionally suffers from catatonia:

the last time i went dancing with him i started to go a bit vague. i told him about my catatonia. i said if i collapse not to panic. but to ring my flatmate or the hospital. or just drive me home. (19)

In part three, her disorder is described again, this time in clinically precise language:

catatonia - after a certain period of excitement, which is characterised by agitated, apparently aimless behaviour, the catatonic slows down, sooner or later reaching a state of total passivity, withdrawal, & almost complete immobility. in most cases, the catatonic resembles a statue. (20)

It is possible to interpret the vulnerability of the female narrator, that is, her "catatonic" response to the man's sexual advances, as evidence she has been subjected to a prior, although undisclosed, sexual attack which has left her traumatised. Bouson argues that traumatic events produce "profound and lasting changes in physiological arousal, emotion, cognition and memory" (7). Because the traumatic event cannot be fully incorporated into consciousness at the time it is experienced, it returns to plague the victim in future. A situation that appears innocuous and unthreatening to most people may be interpreted by the sufferer of post-traumatic stress as threatening, triggering a variety of unpleasant and, at times disabling, defensive psychic and sensory responses (Bouson 7). The woman's reaction, when the man touches her breasts and subsequently removes her shirt, is to experience a splitting off of her psyche and her body. Her state of paralysis affects both the movements of her limbs and her ability to form words into speech and is so acute that she experiences difficulty breathing: "i suffocate on mouthfuls of pink cotton. begin to fade away. my face still & blue" (22).

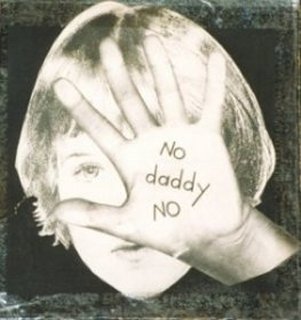

[Above Left] Strange Woman with the Restraining Order, (Marker/paper 21cm x 30cm) (Artwork by Coral Hull, 1994), [Above Right] No Daddy No (Artwork by Coral Hull, 1991)

"The Statue" depicts the male speaker as insensitive, selfish, and determined, at whatever cost, to fulfil his sexual desires. He views the woman not as a person, but as a disembodied object or thing with sexual orifices and zones: "a wet crotch. erect nipples. a dead mind. just the way he likes them" (23). The sequence concludes with the man attempting to rape the catatonic woman who suddenly 'comes to her senses.' Roused from a state of semi-conscious paralysis, she fights back by smashing her fists against his neck. She also wittily finds her voice: "if you had raped me. i would have rung the police. i look at his face. but the man is a statue. he has no reaction to this" (24). The term 'statue' is transposed from a metaphor for the female speaker's physical and psychic vulnerability into a description of the male speaker's shocked inability to respond to her sudden determined and feisty self-defence. "The Statue" is an important and daring text. The female narrator's intelligent and self-aware internal monologues in combination with her articulate descriptions of the experience of catatonic dissociation invite the reader to hear the 'strange' and disruptive speech of trauma.

Hull's and Albiston's depictions of women's sexual exploitation associate the higher incidence of violence against women with hegemonic images and representations of female bodies as sexual objects. In a courageous move, the poets' open the doors to women's often silenced or ignored experiences of sexual harassment, assault, and abuse, placing them centre stage. It follows that by bearing witness to rape and sexual abuse by speaking the often unspeakable, Hull and Albiston contribute to the social process of removing some of the shame and stigma surrounding these experiences.

[Above] Empty World (Mixed Media/paper 42cm x 59cm) (Artwork by Coral Hull, 1988)

Bibliography:

Albiston, Jordie. Botany Bay Document. North Fitzroy: Black Pepper, 1996.

---, and Diane Fahey. Nervous Arcs; The Body in Time. Melbourne: Spinifex, 1995.

Bouson, J. Brooks. "Speaking the Unspeakable: Shame, Trauma, and Morrison's Fiction." Quiet As It's Kept: Shame, Trauma and Race in the Novels of Toni Morrison. Albany: State U of New York P, 2000. 1-21.

Bovenschen, Sylvia. "Is There a Feminine Aesthetic?" Trans. Beth Weckmueller.New German Critique 10 (1977): 111-37.

Cahill, Ann J. "Foucault, Rape, and the Construction of the Feminine Body." Hypatia 15.1 (2000): 43-63.

Felman, Shoshana. "'Education' and Crisis, or the Vicissitudes of Teaching." Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History. Eds. Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub. London: Routledge, 1992. 1-56.

Foucault, Michel. "Truth and Power." The Foucault Reader. Ed. Paul Rainbow. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1986. 51-75.

Grosz, Elizabeth. Volatile Bodies: Towards a Corporeal Feminism. St Leonards: Allen and Unwin, 1994.

Hull, Coral. How Do Detectives Make Love? Ringwood: Penguin, 1998.---, David Curzon, Philip Hammial, and Stephen Oliver. The Wild Life. Ringwood: Penguin, 1996.

Irigaray, Luce. "Sexual Difference." Trans. Séan Hand. The Irigaray Reader. Ed. Margaret Whitford. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991. 165-77.

---. This Sex Which Is Not One. Trans. Catherine Porter with Carolyn Burke. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1985.

Kennedy, Rosanne. "The Narrator as Witness: Testimony, Trauma and Narrative Form in My Place." Meridian 16.2 (1997): 235-60.

Kristeva, Julia. "Julia Kristeva." New French Feminisms. Eds. Elaine Marks and Isabelle de Courtivron. Amherst: U of Massachusetts P, 1980. 165-67.

---. "Powers of Horror." The Portable Kristeva. Ed. Kelly Oliver. New York: Columbia UP, 1997. 229-63.

McLaren, Greg. "The Sky Existed with or Without Observation." Rev. of How Do Detectives Make Love? by Coral Hull, and Race Against Time: Poems, by Lee Cataldi. Southerly 58.4 (1998): 219-27.

Ostriker, Alicia Suskin. Stealing the Language: The Emergence of Women's Poetry in America. Boston: Beacon, 1986.

Rich, Adrienne. What is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Poetics. New York: Norton, 1993.

Ryan, Gig.. "If I Had A Gun." The Penguin Book of Modern Australian Poetry. Eds. John Tranter and Philip Mead. Ringwood: Penguin, 1991. 439-41.

Wooley, Susan C. "Sexual Abuse and Eating Disorders: The Concealed Debate". Fallon, Katzaman, and Wooley 171-211.

About the Writer Melissa Ashley

|

Melissa Ashley is a poet and fiction writer who lives in Melbourne, Australia. Her first collection of poetry and prose "the hospital for dolls", funded by an Arts Queensland Individual Writing Grant (2001), will be published in 2003 (PostPressed). She is currently writing the second draft of a novel (working title "the weird sisters.") She is the former assistant director of the Subverse: Queensland Poetry Festival (1998-2001), and co-ordinator of The Arts Queensland Award for Unpublished Poetry. Her work has been published throughout Australia and overseas in various journals and magazines. In 2002 she completed an honours thesis in contemporary Australian poetry at the University of Queensland. Melissa lives in Melbourne, Victoria. |

[Above] Photo of Melissa Ashley by Stephen Booth, 2001.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.7 (March, 2003) |