ON POETS BEING PAID FOR THEIR WORK

By Geoff Page and Alan Gould

[Above] Man and Bird (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, year unknown)

Geoff Page says; Given the exigencies most Australian poets work under, the issue of whether to work fulltime at one's poetry or part-time may seem irrelevant. My friend and colleague, Alan Gould, and I have spent many hours chewing on this topic. He has never really had a fulltime job since he started serious writing back in the late 70s. I had one for the whole of my writing career until the beginning of 2002 when I retired after 38 years secondary English teaching. His efforts have been devoted substantially to prose though he has produced at least eight books of poetry; mine have been devoted primarily to poetry with just two novels and a couple of other non-fiction works. He is nine years younger than I and our output is, in terms of books, roughly the same.

So what does this mean? Alan is prone to argue that not having a day job leaves one free to devote one's best hours to writing. It also leaves time for more extensive reading and ruminating than is possible with a fulltime job. It's impossible, argues Alan Gould (and Jesus Christ) to serve two masters. One has to give writing one's best shot. Financial uncertainty and the lack of superannuation are just two hardships that go with the territory, he says. And indeed they may stimulate production (though, to be fair, he hasn't quite argued this and, as a current member of the Literature Fund, is no believer in the poet-in-the-garret cliché). Indeed Alan has gone on to argue that writers of reasonable talent and output who choose to devote themselves fulltime to their writing and forswear other employment should be sustained by the state on a reasonable wage.

|

At first glance, all this seems morally and intellectually persuasive (even if the Literature Fund admits it is able to support only a fraction of those applicants who deserve a grant). Writing is a serious and culturally essential business and if exponents of other arts can work fulltime at it then why not writers?

This argument tends to overlook the large numbers of musicians and painters, for instance, who spend many hours teaching their art rather than practising it. Life, as Malcolm Fraser might have said, is not meant to be easy for artists. Perhaps, governments who really valued the arts would sustain practitioners of all kinds (assuming they were reasonably talented and industrious) at a reasonable level (with a guarantee of at least an average wage at the end of their annual labours). |

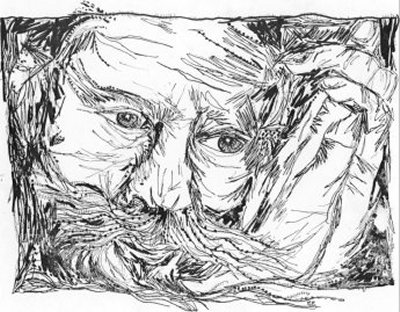

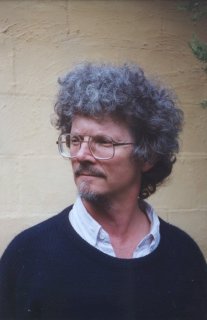

[Above] Photo of Geoff Page by Jenni Mitchell, 1989.

My argument with Alan is essentially that even in this utopia all would not necessarily be well. Certainly with fiction it is well nigh impossible to function effectively if one cannot work on the project regularly each day. There are too many strands to lose track of. With poetry, which can be written in repeated bursts, the opportunity to work on it fulltime 48 weeks a year may not be necessary; indeed may even be counterproductive.

I¹m forced to this view by at least two considerations. One is the outstanding aesthetic achievements of poets such as Wallace Stevens and William Carlos Williams who worked at insurance law and medicine respectively for more than forty years yet produced work which, at its best, is going to be read for centuries. Even T.S. Eliot spent a lot of time in Lloyd's Bank and Faber & Faber. Did their contemporary, Ezra Pound, fare any better aesthetically for all his freedom in living hand-to-mouth? I think not. Indeed it is rare for a poet in any culture to sustain himself or herself entirely on their earnings from poetry. Tennyson built a big stone house with his and Pablo Neruda lived in three houses but these are the exceptions rather than the rule.

The second consideration is that it rarely does a poet any damage to be involved in the world of work rather than simply observing it at an angle (which is not to say that I would rather dig the ditch than watch someone else doing it!). Work is a very large part of what his or her audience knows and they will not be put off to feel that the poet knows it as well as they do. This would include the frustrations of hierarchy, the boredom of meetings, need for preparation at home etc.

|

Obviously there are some jobs which leave little time for writing afterwards. Hard physical work is one of them. There are not too many farmer poets, for instance, and even David Campbell wrote quite a bit more poetry when he had more or less retired from it. And, of course, there are many promising poetic careers which have been lost to academia with its insistence on publishing articles about other poets' work rather than working on one's own. Apart from these extremes, however, it is possible to be an honest and effective worker or professional in many fields and yet, at the same time, be a good poet. |

[Above] We Can Make Peace (Artwork by Coral Hull, 1993)

I will concede to Alan that it is rare to be equally good at both. Philip Larkin was probably a better poet than a librarian but there don¹t seem to have been too many complaints about his cataloguing or shelving. Sometimes, for example in secondary English teaching, the skills of writing poetry and the day job of teaching it overlap or reinforce each other. One knows the subject from the inside, as it were and has the necessary enthusiasm for it. The trick is to serve your two masters equally and not give too much to the one who pays more. This is a delicate tightrope which writers like Alan, understandably, prefer not to tread. And of course it would be a great loss to both poetry and English teaching if all English teachers were poets and all poets were English teachers. The fact that they¹re not reminds us, indeed, of how much the diverse employments of poets is a part of their poetry.

A third argument for serving two masters is a psychological one. If you are reprimanded by one master (say a bad class) you are unlikely to be berated by the other at the same time (say a rejection slip). One doesn¹t have all one¹s eggs in the one basket. Poets who work only on their poetry tend to approach their mailbox (snail or e) with a trepidation which can soon lead to irritation, even rage, and quite often paranoia. To have a fallback position leaves one room to move. The wounds inflicted by one can be licked and healed rather than picked at and made worse.

I don't think, however, that serving two masters means poets shouldn¹t periodically be given the experience of serving only one. There is a strong argument for short grants, for instance, where the poet is free to organise and finalise a manuscript before sending it off to a publisher. There is an argument for research time, if the work is a verse novel or a livre composé. But ,if a poet is not free to spend a lifetime reading and ruminating, his work will not necessarily be the worse for this shortcoming. There are ruminations and ruminations.

I might say, in conclusion, however, that my present experience of writing (more or less) fulltime on a reasonable retirement pension is a pleasant one. But, then again, I had to work 38 years fulltime (with a few Literature Fund grants, I must admit) to get it. It would have been a little less enjoyable writing this present article if I were still thinking about a class I had to give tomorrow at nine. But it can be done and has been done. And I¹m not at all sure readers would notice any real difference between the work written under pressure and that done in a world of work-free tomorrows.

About the Writer Geoff Page

|

Geoff Page is a Canberra poet who has published thirteen books of poetry, two novels, a biography, a book of short stories and poems and edited two anthologies. With time off for occasional short grants or residencies Geoff Page has worked full time running the English department at Narrabundah College in the ACT since 1974. He has also either read his poetry or talked on Australian poetry at Berne, Switzerland (1984), Beijing (1988), London, Lecce and Bologna (1992), Guangzhou (1994), Singapore (1995) and New Zealand (1996). He was also one of four Australian poets on a reading tour of North America in 1985. He has been Writer in Residence at Wollongong University, the Australian Defence Force Academy, Curtin University and Edith Cowan University. |

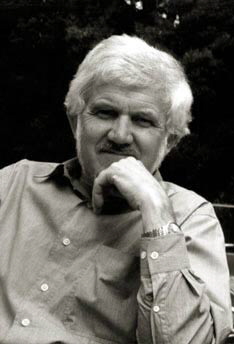

[Above] Photo of Geoff Page by photographer unknown, year unknown.

Alan Gould says; Poetry And Real Work!

Since Geoff uses my views extensively in his defence of part-time writing, let me state in my own words what these views precisely are.

Geoff’s account of my credentials is not quite accurate. I date my literary career from the acceptance of my first sizeable work which was taken by The ABC in November 1972. I had been writing seriously for at least two years before that. I have published ten, not eight, collections and since 1984, when my first novel appeared, I have alternated a poetry volume with a work of fiction. Before that date I devoted myself almost entirely to poetry and the reviewing of poetry. Thus I would assess my experiences as a writer of poetry and fiction as roughly equal, and my valuing of the respective arts likewise.

The exact formulation I use when arguing for a full-time approach to writing is this. When imagining and making a work of literature, my desire to get the thing vivid, whole and true is such that I believe it requires nothing less than my first self and my best self, and I cannot comprehend anyone with a similar desire wanting to give it anything less.

I phrase it in this way because I believe it to be a principle, not a schedule. It is the principle that recognises poetry is not only a vocation but a profession. The goal of the vocation is to bring into full presence and intelligence the world that beckons a given writer to express. The goal of the profession is to come as fully as skill and understanding allow into the language-at-large and make it one’s own instrument. Being a profession, there are the requirements and resources of a profession, procedures (or the nous-to-dispense-with-procedures), craft, tact, tricks and knacks, but above all, experience-on-the-job.

|

Is it so high-minded, I wonder, to expect poets with a respect for their calling to enter upon their poetry full-time? Would you trust your car to an auto-electrician distracted by his main employment as an accountant? Would you trust the removal of your appendix to the surgeon whose working day is devoted to his newsagency business? If we expect focus from our various mechanics, surely it is reasonable to expect poets, those intellects that we trust to think and feel at the very nexus where a culture expresses its health and mental range, to do so in hours when they have not been fatigued by a day of distracting employment.

Or, to turn this argument around the other way, are writers likely to come into the full powers of their imagining, to find the reach of their expressive powers, at the end of a day where they have been bored to stupor by a procedural meeting, fretted by a class of malignant year nines, or driven distraught by a screen’s ledger of numbers that will neither add up nor disappear. |

[Above] Photo of Alan Gould by photographer unknown, year unknown.

I do not recall ever having argued that full-time writers of reasonable talent should be sustained entirely by the state, as Geoff asserts I do. Like other writers I want my books to be read by those motivated to buy them. I relish the relationship between my efforts and an individual’s willingness to pay money for them. Indeed I have often declared that The State does not owe the writer a living because it was the writer’s choice to undertake so risky a livelihood in the first place. I do, however, welcome state assistance on the principle that a work-of-art may not earn the artist a livelihood in his/her lifetime, but can continue to earn its living beyond the lifetime that produced it.

The culture benefits from this, and might therefore, in fairness, pay some anticipatory royalty rather than allow its writers to starve. That’s a socialist idea, and among the socialist ideas I’ve supported in this regard are Les Murray’s royalty supplementation idea, where the state pays a supplementary royalty above that of the publisher up to an agreed cut-off point on all books produced by credible firms. I call this socialist because it seems to me an egalitarian way by which the state can accord value to the vocation of writing. But I have never supported a Soviet-style sinecure for select poets. A part of literary income must come from the market in order that a writer knows whether there is real interest in his/her work. But a benign state will recognise that the market does not pay the full value of a work of art, and will, in its benevolence rather than its ill-conscience, remedy that situation.

Work and real work, ho ho! It has certainly never done me any damage to be involved in the world of work. During the half dozen or so builder’s labouring jobs I held on various Canberra sites between 1967 and 1973, I dug a good many of those ditches where Geoff may have been so shyly watching. My hands are familiar with the steely hexagon of a crowbar, the distinction between the long handled and short handled shovel, the two blades of the pickaxe etcetera. I recall the jackhammer and kanga-hammer, the ramset nailgun, the wheelbarrow of treacherously sloppy cement and the narrow scaffolding along which it had to be manouvred. Also the sulphuric acid used to clean down bricks which got under one’s rubber gloves to streak armpit and forearm with burns.

|

A year or two after these employments I taught in those anarchic schoolrooms Geoff mentions. Both the ditches and the schoolrooms have gone into my fiction, and more rarely my poems, when I have wished to evoke the world of work. They enter my writing by virtue of my having a memory, like everyone else. Of course a person entirely quarantined from the world of work has a smaller world to find in his/her literary imagination. But I maintain that a sufficient taste of one workplace or another is different from a lifetime as a wage slave. Besides, the human mental faculty is a projective one. We call it, after all, an image-ination. Shakespeare, so far as we know, was never a sailor, soldier, or undertaker, but he was able to image credible types of each in his plays.

I have never been a baker. Yet I can observe in a bakery much of the condition of bakers and from that imagine the experience of bakers. I can take my opportunities to talk to bakers, to smell the doughy staleness on the clothes on my son when he comes home from a day of having made pizzas and burgers. |

[Above] Thinking Thoughts (Artwork by Coral Hull, 1991)

The world is so full of clues that I believe both Geoff and I could write about bakers without making any bread in their trade and, of course, not much from such an exercise in ours. I have certainly written, (evocatively I believe), about the lives of mechanics, roof-tilers, electricians, without having worked in these occupations. A poet is involved in the world of work, not by being on a salary slip, but by being sentient.

My last point is my most tendentious.

I believe, but cannot prove, that many of the poets we admire, who had full-time salaried jobs, were in fact giving to the calling of poetry their first and best selves. I refer to the likes of Slessor and Hope, Stevens and Williams, Larkin and Eliot. The human imagination is a shy, yet protean capability. If I envisage the day-to-day consciousness of, say, Slessor the journalist, or Larkin the librarian, I see human beings who became adept at very subtle strategies indeed to keep the cover-employment as precisely that, a ‘cover’, while protecting a primary energy, a prior claim, by which they could pursue what I have no doubt they would have called their more vital, their more absorbing work. This implicit tension is especially poignant in Slessor’s war diaries where the reader can witness the prolonged, insidious effect of desert-travel, routine, professional expectation, on the sacrosanct-ness of Slessor’s ‘cave-of-making’ during the time his writing of poems petered to nothing.

It may be the very secretiveness of such mental strategies, and the pressure of them, are in these cases, a part of the actual creative dynamic for that more ‘vital’ work. My question is, if this conjecture is accurate, how much more vivid, resonant, far-reaching, ample, surprising, might have been the opus of both poets had their time and, more importantly, their first and best selves, not had the claims made on them by their cover employments? With Shakespeare, Auden, Judith Wright, Les Murray, the question does not arise. And in the end we must also let it drop when applying it to the likes of Slessor, and Larkin, because it is enough to be grateful for the luminous poems they gave us. However, accepting that some poets managed to write luminously despite distracting employment is quite different from defending such employments as an essentially useful complement to creating art. I think that latter proposition is dubious.

About the Writer Alan Gould

|

Alan Gould was born in London of English-Icelandic parents, and lived on armed forces camps in England, Northern Ireland, Germany and Singapore before coming to Australia in 1966. He has an arts degree from The Australian National University, and a Diploma Of Education From The Canberra College Of Advanced Education. Since 1973 he has written poetry and fiction as full-time as resources have allowed, augmenting his income with literary journalism and relief teaching. In 1981 he won the NSW Premiers Prize for Poetry, 1981, for Astral Sea. Other Awards include; Foundation of Australian Literary Studies Medal for the Best Book of the Year, 1985, for The Man Who Stayed Below, National Book Council 'Banjo' Award for Fiction 1992 for To The Burning City, The Phillip Hodgins Memorial Medal For Literature, 1999 and The Royal Blind Society Audio Book Of The Year (for The Tazyrik Year,) 1999. He has been awarded several fellowships from The Australia Council of the Arts. |

[Above] Photo of Alan Gould by Anne Langridge, 2000.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.7 (March, 2003) |