WORKING AT KEIO UNIVERSITY IN JAPAN

By Rebecca Edwards

[Above] Tokita Masako and Rebecca Edwards at the launch of 'Dreams of Flying',

Atelier-Gym. (Photo by Kameyama Tetsuro, 2001)

From September 2000 to February 2001 I was an Asialink writer-in-residence at Keio University, Tokyo. I had six months in which to explore Tokyo and to write, whilst teaching a course in Australian literature (2 contact hours a week) at Keio.

This was not my first experience of living in Japan; I spent a year when I was sixteen as an AFS exchange student, the guest of a very brave family in Hiroshima prefecture. My host-mother, Yuri Hori, taught me how to speak Japanese from scratch; I knew absolutely none when I arrived off the bullet-train at Fukuyama Station. All my life I had taken my ability to communicate - in conversation, in writing, and in body-language - for granted. Now I was suddenly inarticulate, incapable of explaining myself, mystified by people's actions, and their reactions to me. I was a huge stumbling baby, putting my foot into it both literally and metaphorically, a dumb alien that my friends led around by the hand, pointing things out, trying to warn me that I was about to commit another terrible faux pas, apologising for me afterwards.

In that year my host-family and friends did their best to teach me how to speak, think and behave like a good Japanese girl, they taught me with kindness and patience. It must have been like trying to teach a great dane to drive a bus. But I loved them with all my mute and alien heart.

At the time of the Asialink Residency to Keio I was 32, had studied Japanese language, literature and culture at the University of Queensland for four years, and had had my first full-length book of poetry published in my own language. I was going back to Japan with a working-knowledge of the language (albeit a little rusty) and with the deeper knowledge, or acceptance, that however hard I tried, I was never going to pass as Japanese. I was going to be an Australian writer in Tokyo, not an uncertain adolescent, but a reasonably confident young woman, with a reasonably developed sense of self.

The Keio International Residence: A Fine and Private Place

ATTENTION!!

|

Recently, we received a following mail of complaint:

There is someone who lives here who has a SAXOPHONE, and they

practice in their Room until late at night, this causes several probrems...

We have the "REGULATIONS AND PROCEDURES FOR THE

RENTING AND USE OF ACCOMMODATIONS IN THE KEIO

INTERNATIONAL RESIDENCE". No. 10 of this Regulation is "Noise

or cooking-smell nuisances to the neighbours should be kept to a

minimum. (This file is in every room) We think all the residents agreed

with this regulation.

BE SURE TO OBSERVE THIS RULE.

Thankyou for understanding.

Keio International Center

A piece of standard advice for anyone about to participate in a residency overseas (or, indeed, in one's own country) is to keep an open mind. Remember that your expectations and plans are only first drafts, which will undergo many revisions. |

[Above] 'Aa-ah!' salt, vaseline, porn-manga, new year's biscuits, ink, tin box

from non-burnable rubbish day, 2001. This is part of a mini-installation at Umbrella Studio, in Townsville, at the end of 2001. I'd had the biscuits for a year, and they were still as hard and disgusting as they had been in January. I decided to use them in artworks in a members' exhibition titled 'Parallex'. Even after being caked in vaseline, or painted over in ink, it took them months to deteriorate. I ended up burying them in their boxes. (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, 2001)

It isn't possible or even advisable to embark on a residency without any expectations at all, but it's very unlikely that the reality will coincide with your projections. Be prepared both for disappointments, and for unexpected blessings.

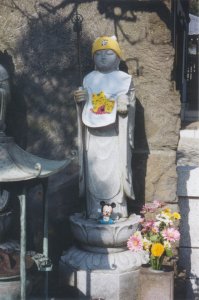

I knew that the shift from Townsville, North Queensland, with its abundant bird and animal life, to the 'built', almost entirely human, environment of Tokyo would be a shock for me. I was looking forward to the effect that this, and other unexpected shocks, would have on my writing. I took a notebook, sketchbook and camera with me on my travels. I found many interesting, and even beautiful, places amongst the ferro concrete and steel; many of these were Shinto shrines, and others were Buddhist temples, or tiny wayside shrines for jizosan, the guardians of the dead.

And, perhaps predictably in this hugest of cities, I found myself to be terribly alone. I brought some of this loneliness with me - the Residence does not accommodate children, and I had made the decision to leave my seven-year old daughter with her father, for six months. This was by far the longest time we'd been separated, and I still don't know if it was the right decision or not.

[Above] 'Crying Moon', pen and ink, carbothello pencils. This is one of the late-night images I made in my room, in the residence at Keio. (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, 2000)

I must confess that I wasn't even conscious of the kinds of expectations I had when I learned that I would be staying at the Keio International Residence, Tokyo. The name of the place evoked a cosmopolitan atmosphere, and I imagined meeting other residents - post-grad students and teachers from all over the world - in the common room, swapping information and stories over mugs of tea, after a day's teaching and writing.

I am a loner by nature, and relish time spent in my own company, but, I admit it: I expected a common room, and the occasional company of other human beings. Instead, what the International Residence afforded me was an immaculate solitude. I knew there were other people around, because I heard doors opening or closing. Although I didn't ever hear the saxophone player I knew that my neighbour snored, and sang very sad songs in a soft, male voice; and occasionally I smiled and nodded to people on the stairwell, or in the lift. But a hallway isn't a place for conversation, and after swapping names and countries, we would disappear into our private cells.

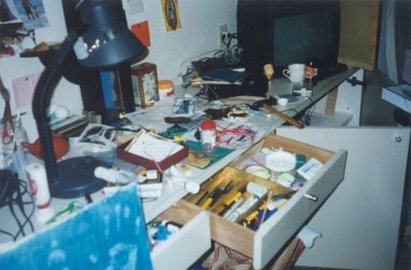

My apartment, luxurious by Tokyo standards, was fully equipped with a bed, a desk, a huge television, a minute kitchen-alcove, and a spotless bathroom. It was my living and work space for the next six months, and I got to know it very well. Because there were NO distractions, I did a lot of thinking, reading, and writing, an enormous amount of art-making, and a fair bit of drinking in that little room.

Just outside this hermetically sealed capsule was Mita, Tokyo. A fifteen-minute trot to the nightclub zone of Roppongi, a few train stops in various directions to the glittering Ginza, trendy Harajuku, touristy Asakusa and cultural Ueno. I could see Tokyo Tower from my tiny veranda. The university itself was a five-minute walk away, the Australian Embassy was just up the hill. The first couple of weeks, before classes began, I went exploring, on foot and by train.

[Above Left] My desk, Keio Residence (Photo by Rebecca Edwards, 2000) [Above Right] My room: the kitchen and front entrance, Keio University Residence. You can just see my bedhead in the top left corner. (Photo by Rebecca Edwards, 2000)

The first thing I noticed about Tokyo was the stink. When I arrived it was late summer, and the streets were lined with very tidy, but massive piles of garbage, every night. The book of rules and instructions in my room told me what I could put out when: non-burnable rubbish on Mondays and Wednesdays, burnable on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and recyclable on Fridays. On non-burnable days the smell of decomposing food scraps pervaded the streets, even though all garbage is tightly wrapped in plastic bags, and then covered under blue nets, to keep out the huge, glossy, well-fed Tokyo crows. The Japanese are famous for being tidy and clean to the point of obsessive compulsion - cleanliness is godliness - but a city of 20 million people makes a lot of garbage.

Thus, walking around my little patch of Tokyo, exploring and familiarising myself with my environment, meant being confronted with the vision and smell of human waste. I would step out from my spotless, airconditioned bedsit, into the hot, greasy, smelly Tokyo streets. The Residence was quite near a river, which at first I thought was a kind of open drain; it stank too, and steam erupted from fissures in its bricked-up banks. The backs of shops, restaurants and tiny industrial sites rose straight up from its opposite bank, and a wide flyover followed the watercourse, dooming it to shade.

Sometimes the thick, brown water at Mita drained away, exposing slimy pebbles, a few wrecked umbrellas, and tarnished bottletops. On later night walks I would spot a pair of ducks, paddling on this dead, or terminally ill, river, and I wondered what they found to eat.

[Above Left to Right] O-jizo-san at Kamakura. O-jizo is the Buddhist guardian of the dead, and his image is found in temple precincts, which also serve as cemeteries, and at sites of accidents, such as crossroads and train crossings. Women who have lost a child or foetus make bonnets and bibs for the o-jizo-san who is looking after their child, and place flowers, toys, and water at his feet. (Photo by Rebecca Edwards, 2000) A poor man pulling a cart loaded with cardboard through the Ginza, early morning, September. (Photo by Rebecca Edwards, 2000) Man feeding pigeons at Hachimangu, a shinto shrine-complex in Kamakura. (Photo by Rebecca Edwards, 2000)

Of course, I didn't expect to find a pristine river in the heart of Tokyo, and I was surprised and happy to see live ducks at all. What really threw me in those first weeks and months was the discovery that, despite having grown-up, despite my functional Japanese, despite being a published author on a prestigious residency, I was just a shadow of myself when I stepped outside my door. I described it in my journal as 'feeling as though I'd lost half my personality'; of being separated from that sense of self that is created by how we interact with others: our family, our peers, our countrywomen and men. In Tokyo, that busiest and most reserved of cities, nobody saw me, and nobody spoke to me, except to offer me directions or to serve me in a shop.

Luckily, I had two very good friends in the outskirts of Tokyo, the photographer Takuya Suzuki, and his wife Keiko. Their phonecalls and visits were vital to me, and their baby Kyosuke had to fight me off, as he was the only person I could legitimately hug. Hugging isn't something one does, in Japan, and Kyosuke knew it, but I stole hugs and kisses from him anyway.

I was also very lucky in that I had some 'borrowed' friends - friends of a good friend in Townsville. Shibata Tomohiro and Kameyama Tetsuro made time in their incredibly busy lives to look in on me, feed me, and keep me sane. When they took me for drives in the countryside or meals at restaurants I felt as foolishly happy as a dog being taken for a walk; I tried to look and behave like an elegant poet, but I felt like sticking my head out of the car window and drooling into the wind.

[Above] A class on children's literature, during the course on Australian Literature and Culture at Keio University. We're looking at Jeanie Adams's 'Going for Oysters'. (Photo by Kawamura Kimiko, 2000)

The Work

Having to prepare and teach a course on Australian Literature and Culture - I'm still not quite comfortable with the distinction being made in this title! - made me realise how little I actually knew about the arts in my own country. I took a hundred or so books over with me, planning to give them to the university to flesh out their (almost non-existent) collection of Australian titles. I also borrowed books and videos from the Australian Embassy's library.

I began each of my lessons with a song from a CD or tape: Midnight Oil's 'Truganinni in Chains', Yothu Yindi's 'Treaty' and 'Mabo', Paul Kelly's 'Sweet Guy Waltz', Archie Roach's 'Took the Children Away'. I showed my nine students the first part of Women of the Sun: 'Alinta the Flame', which deals with an Aboriginal tribe's experience of first contact; 'Canetoads; an Unnatural History'; and 'Picnic at Hanging Rock'. I read them poems by Lionel Fogarty, Samuel Wagan Watson, Coral Hull, Gig Ryan, Judith Wright, Les Murray, Anthony Lawrence, Kath Walker, Ania Walwicz and Gwen Harwood. We read Lawson's 'The Drover's Wife', Baynton's 'The Chosen Vessel' and selections from Weller's 'Going Home' stories.

It was a frankly biased course, veering towards Aboriginal, female, and/or queer

artists, and steering away from areas I feel hugely ignorant about, such as theatre and dance. It was offered to students from any field who wished to improve their English, and had some interest in Australia, and I was very pleased to find that two of my students were extremely knowledgeable about Australian culture and politics. I was a great disappointment to one student, however; the captain of the Japanese cricket team. He told me in his reading journal that he prayed to Donald Bradman every night to make him a better cricketer, and I was sad when he dropped out of the course.

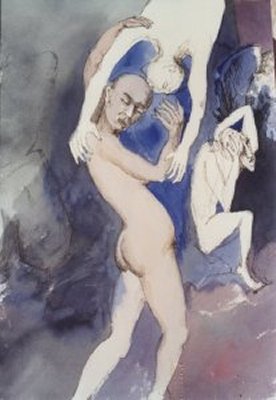

[Above Left to Right] 'Lover', watercolour, pen and ink. (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, 2000) 'Self-portrait as a Disease'. This work was begun during a residency at Bundanon, Arthur Boyd's property on the Shoalhaven. I took a photo of myself, and worked on it with ink, river sand, and pin-scratching. Whilst staying at Bundanon I read that the Wodi Wodi, the traditional people, were decimated by smallpox introduced by white settlers. The riverside was so quiet and empty, and I felt haunted by the people who should have been there, living on that fat country. The work was finished in Tokyo, using a board I found in the rubbish, and acrylic paints. I wanted the shape under the photograph to be reminiscent of a log coffin, and of absence. (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, 2000)

Burnable Rubbish

If, like me, you love to recycle things other people have thrown away, then Tokyo on Tuesday and Thursday nights is paradise. My host-mother would have died to see me 'beachcombing' along the streets of Mita and Azabu-Juban, rescuing beautiful wooden and cardboard boxes, building materials, and books, from the neat stacks of burnable rubbish. I couldn't stand to let them be carted off to the incinerators. Outside a doll-shop I found metres of felt and gabardine; absolutely new, absolutely clean; outside a framer's I found cardboard and foamcore. I began making things, combining my found materials with seeds and feathers I'd brought from home, and stitching small strange creatures.

Some nights I went on these expeditions with Eva Havlicova, a post-grad from the Czech Republic, and my first and only friend from the International Centre. Once she found me a scroll, complete in its beautiful wooden box, in a pile of 'rubbish'. We laughed rather furtively at what our students would think if they sprang us shuffling around like old bag ladies. "It's alright for me," said Eva, "I'm from an Eastern Bloc country. But you are a rich Australian, and a disgrace."

After these forays Eva and I would buy beer from an automatic vending machine, and drink it in my room. It was getting pretty crowded in there, with all my scavenged boxes, tins and books. I had a life-sized samurai too, from the bin outside a video-shop - I'm still very sad that in the end I had to leave him behind (along with a pair of skis, and an entire shipping encyclopedia). Eva translated the interesting junkmail that appeared in our letterboxes. Many fliers were for call-girl services with names like 'Delivery Girls'; and for 24-hour in-your-room 'Pink Massages'. I was impressed with how many flyers I received, at their glossiness and blunt pricings, and I started making pieces that incorporated them. (Alright, I suppose I should confess here, that, until Eva enlightened me, I'd thought that the massages on offer were simply what they professed to be: 'Relaxing' and 'Convenient'. In fact, I'd been planning to get one myself, as I'd been having trouble sleeping.)

[Above Left to Right] 'Birth of Karma', watercolour, pen and ink. (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, 2000) 'Lie Fairy', calico, watercolour, beads, 2000. My daughter, Miriam, called me one day and confessed that she had told a lie to her dad, about a bronze sculpture she was helping him make. She'd cut its arm on purpose, not by accident at all. So now her dad was making her a 'lie fairy'. I wanted one too. (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, year unknown)

Blessings: Mr Yoneyama and Atelier-Gym

About a third of the way into my residency, I wandered into a gallery a few blocks away in East Azabu, attracted by some crazy jeans that had been stitched, bedecked with beach glass, bits of metal and pebbles, and sprouted little fingers, tails and penises. The exhibition was called 'Dress/Undress', and these particular pieces were by an artist called Masako Tokita, the gallery director explained. In fact, he and the artists were having a party at the gallery on Sunday, and would I like to join them? It was the first kindness from one of the kindest people I have ever met. At the party on Sunday, not only did I meet a kindred spirit in the form of Masako Tokita, but, when he found out that I made art, Mr Yoneyama invited me to have an exhibition at Atelier-Gym. I was thrilled.

So the highlight of my writing residency turned out to be a two-week exhibition of drawings, papercuts and 'intimate sculptures' (or weird dolls, if you prefer) at Atelier-Gym. Mr Yoneyama gave me the space, paid for the invitations, and had the drawings matted and framed. Mrs Tokita organised a feast at the launch, and the Australian Embassy pitched in with some bottles of red. At the launch I realised that I had a roomful of interesting friends and acquaintances. The generosity of Mr Yoneyama of Atelier-Gym was not something I could have dreamt of, as I packed for Tokyo five months before.

The writing has developed much more slowly, and the best of what I began in Tokyo is actually about Australia. Homesickness, research for the course, and re-immersion in another language seemed to focus my attention on what it is to be 'an Australian'. Also, I felt strongly that I wanted to write something other than the 'souvenir poem' that is a foreigner's first impressions of another culture, and I probably need to live in Japan for a lot longer, before I can achieve this.

|

The following poem was written in my little apartment, after a day's sketching at the Tokyo National Museum. On the surface, it has nothing to do with the experience of being in Japan. Some of what I saw, felt and experienced in that six months has been recorded as a photo or drawing, but it has resisted being put into words. It's as if my hands have decided to speak for me, as they have so often had to do when my Japanese falters, and when my poetry is no use at all.

from Book 2 of Holiday Coast Medusa

There's a Heritage Bar in every town in Australia.

An RSL

a school of arts building

and, on the coast, a beach called Shelly

whether it's shelly or not.

There's a Criterion Hotel in Rockhampton

and in Townsville; "come for a drink at the Cri"

"come for a drink at the Heritage."

The street names repeat themselves, named for blackbirders

explorers, peers and royals: Victoria, Salisbury

Sturt Sturt Sturt.

Creeks are called Deep, or Sandy

or Massacre.

There's an Anzac memorial, white-washed concrete and marble,

concrete wreaths and names, the same names repeating,

a dominant theme with minor local variations:

Laverty and Johnston

Phillips and Hargraves, Brown, Smith, Jones.

There's usually a big something-or-other; the Merino at Grafton

the Prawn at Ballina

the Maroochydore Pineapple.

Coffs, with the highest level of birth deformities

in the country, from the spraying of those hills of blue bags,

celebrates with a Big Banana.

I've been through the Big Banana,

went through the gut of the Merino too, like a worm.

There are always things for sale; caps and keyrings

made in Taiwan. Steak sangas in white breadrolls.

There are always plastic tables, thin white paper napkins,

tinfoil ashtrays.

By the time the local Murris, or Kooris

get their previous ownership recognised

there's usually only one place left

for dot-painted dreamings:

a wall of the public toilet

in the park. |

[Above] Dream of Floating', watercolour, pen and ink. (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, 2000) 'Echidna', Japanese cotton, echidna spines, calico, 2000. The Japanese for echidna is hari nezumi: 'needle-mouse'. (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, 2000)

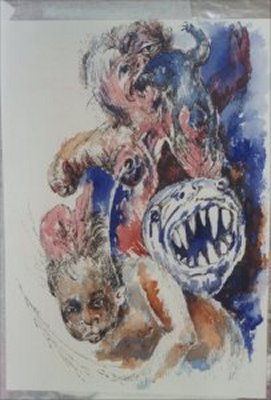

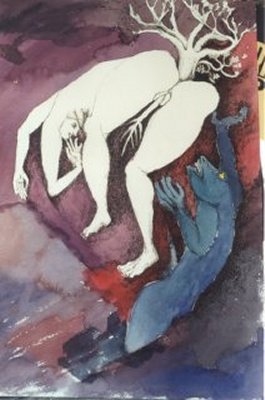

How I worked on my Visual Art in Japan

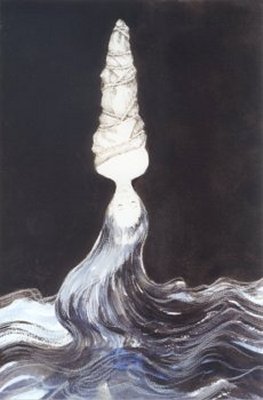

My process: I 'conceive of' an image, say of a woman weeping under a tree, or two people embracing. I draw, and write poetry, to explore this image. I suppose the initial, pre-verbalised image is triggered by something I've read, or dreamed about, or a couple of words I've overheard, but it appears to just 'drop in' to my mind fully-formed, when I am daydreaming about nothing in particular. In Japan, I dreamt again and again of flying over the city. They were very liberating dreams, and I wanted to capture that feeling of 'the power to fly' in my work. And twice I woke up with the impression that a woman with a pale face and very long hair had been staring at me, her face so close to mine that I could see nothing else. I drew this woman a lot, crying, or hanging upside down from a tree. She was very isolated, like me, but she was definitely Japanese.

Some images stay with me for years, and undergo many transformations. The first drawing I have of a figure hunched up under a tree was made when I was seventeen. As with dreams, I often forget that I've made these earlier drawings, until I find them in a scrapbook or folder. They seem new and fresh, every time I make another drawing.

|

For me, drawing, and writing poetry, is about the renewal of themes, both personal and maybe even archetypal. I want them to reach other people on a non-verbal level - to 'explain' them is to diminish them, because they are about exploring places where there are only nouns and verbs - no fully-formed sentences.

It feels as though a huge amount of energy flows out of my eyes, when I'm drawing, and I quickly become tired, physically and mentally, and have to sleep for a while. So I end up with a lot of unfinished drawings, which I go back to at a later date, when I'm fresh again. If I'm lucky, the energy flows on and on, and I don't sleep at all. It's a very intense, blessed time, but I'm exhausted afterwards.

I don't lose my sense of self when I'm creating art. Drawing, or making intimate sculptures, is when I know who I am, much more than at any other time. More than when I'm writing, when I'm with other people, and much more than when I'm in bed with someone; drawing is when I am comfortable with my fluid and deep-shifting nature. |

[Above] 'Mangrove woman', pen and ink and watercolour. (Artwork by Rebecca Edwards, 2000)

What I lose, and it's such a relief, is my concept of self-as-others-see-me. I think drawing allows me to forget who 'I' am, and just enjoy being me.

My preferred working environment is a big, clean, peaceful room with lots of natural light, surrounded by trees, and free from interruption by people or mechanical noises, especially TV. A place where cool, gentle breezes can flow through. A table and chair, a shelf for my tools. Room to move and spread out. Somewhere where I can pin up drawings, images cut from magazines, and things I've picked up on my travels.

The room in Japan was certainly not large, but it was dust-free, and an aircon kept it cool in summer and warm in winter. Its walls were clad in a soft material which meant that every space was a potential pin-board for photos, paper, drawings, feathers, leaves - anything pinnable went on the walls. At one stage there were half-finished sculptures pinned all over the curtains, too. It was peaceful: sometimes noises from the street wafted up, but I quite liked these, as it kept me in touch with the human race. I had adequate light, adequate desk-space, and more than enough privacy. I couldn't say that it suited my ideal requirements for a working space, but it was fun, and cosy. I got a lot done.

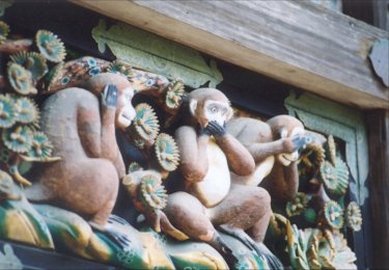

Project Nikko

Thanks to a grant from the Australia Council, I will be returning to Japan in 2003, to write a book of illustrated poems at Nikko. Nikko is a small town in the hills of Tochigi Prefecture, a few hours drive from Tokyo. I have wanted to go there, to see Nikko Toshogu, since I first studied Japanese history at age fifteen. The Toshogu was built four hundred years ago to house the soul of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first and one of the cruelest Tokugawa shoguns, but this is not what excites me to write about it. My host-mother described the Toshogu as 'gorgeous', meaning elaborate, bright, ostentatious, un-Japanese. The photo I saw in my history book was of an incredibly ornate building, a kind of iced and glazed gingerbread house, standing in a forest of huge pines. And I thought I have to go there.

In October 2000 I finally got to Nikko. For one frustrating, car-trapped day a kind friend and I did the Japanese-style tour: see as much as you can in five second snatches, stand in many queues (if hundreds of people are lining up to see it, then it must be good) drive, drive, drive. It was koyo, when the autumn leaves are at their most brilliant; and a part of the Toshogu which had not been open to the public for 300 years was open for a limited time: hence the enormous queues, and the unexpected traffic jam.

What I saw of Nikko that day convinced me that I wanted to stay in the tiny hot-spring town of Nikko, and write. Not just about the Toshogu, although I find it an incredible place. In the silence of a huge cypress forest one wanders through a complex of structures, mostly wooden: god-sized gates, treasure houses, walls, shrines. Every inch is carved: it took something like 15,000 carvers three years to complete, and most of the carvings are painted. As an artist and poet I find it a very inspiring place to be.

When I asked my friend what she liked best about it, she replied instantly: "The trees. We don't have many trees like this left in Japan". They are ancient presences in themselves. I would like to write about the lake, which was wooded, and haunted by tiny stone gods amongst the trees; and the hot-spring resort nearby, where each puddle on the ground was a different temperature. There was a small Buddhist temple in the middle of a steaming swamp, and in that temple a statue of the Buddha, its face blackened by minerals in the steam. And there was a bell which, when struck, seemed to resonate forever.

[Above Left] Ancient guardians at Lake Chuzenji, Nikko. (Photo by Suzuki Takuya. 2000) [Above Right] Three monkeys, carving on a shrine lintel at Nikko Toshogu. (Photo by Rebecca Edwards, 2000)

My plan is to stay four months in Nikko, writing about the environment, and people who live in it, and the gods who inhabit it. It is an extremely fertile place for the kind of poetry which I wish to write. That is poetry which taps into the essence of a place, and its people, rather than tourist grade snap-shots.

I think I can do this, now. Japan has been a part of me for seventeen years - more than half my life - although I am not part of Japan. I know now that I will always be a foreigner, a gaijin, in that country. However, I find being a stranger - looking at a foreign country through stranger's eyes; and looking at my own country from the distance of another country, another language - extremely productive. The challenge for me will be to write about this - to a Far North Queenslander - very alien environment in a way which will engage Australian readers. How can I communicate my passion for this place to my countrymen and women, many of whom have not been to Japan? What can I find, in the landscape, and in myself, which will make this collection significant to readers of many different backgrounds and nationalities? How can I use words, structure, and rhythm to find the heart of an experience, and express it in a poem which lives? It is a challenge which is at the core of my identity, and which constantly informs my poetry.

Since my year's stay in Japan at age 16 I have lived with a sense of being an outsider, of hovering at the edge of things, whether I am in Australia or Japan. Whatever landscape I am in, there is always another landscape travelling at the back of my thoughts, in which the very quality of light is different. I am never quite sure anymore, whether to apply values and thought-processes that I once took for granted, or those which my host-mother struggled so hard to teach me, and which I absorbed as I learned to speak and think in Japanese.

But I suspect that many writers and artists can identify with this vague sense of exile. It is part of our training, to stand back, observe, and analyse, to find expression for what we are experiencing as well as experiencing it. Or perhaps it is why we become writers and artists in the first place - because we can never quite switch off that little cool voice which says 'record it'. At any rate, this sense of being an outsider is one which I find deeply unsettling, and therefore extremely valuable as a power-source for writing, and for making art. With any luck, the book I write at Nikko will be like nothing I've ever written before.

About the Writer Rebecca Edwards

|

Rebecca Edwards is a graduate of the University of Queensland where she majored in Japanese. A poet and visual artist living in Townsville, she has been a guest of major poetry festivals throughout Australia. Her unpublished long poem "Night Is The Smell of Burning" won the inaugural Arts Queensland Poetry Award in 1999. Her first solo art exhibition Little Dangers was held at Flinders Gallery in 1999; a second exhibition will be held at the Perc Tucker Regional Gallery, both in Townsville. She has been awarded an Asialink residency at Keio University, Japan; and, as a recipient of an Arts Queensland project grant, is completing her first verse novel. Rebecca Edwards's publications include two books of poetry; Eating The Experience, (Metro Press, 1994) and Scar Country, (University of Queensland Press, 2000). |

[Above] Photo of Rebecca Edwards by Suzuki Takuya, 2000.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.6 (September, 2002) |