PI O - AN APPRECIATION

By Billy Marshall-Stoneking

[Above] Cover of 24 Hours by ΠO (Artwork by artist unknown, year unknown)

I’d as soon write free verse as play tennis with the net down - Robert Frost

In the late seventies, when performance poetry was something academia only sneered at, it was already becoming obvious - at least to the present writer - that what the poet, Pi O was doing with his poetry was a whole lot more interesting than "playing tennis with the net down". Critics continue to accuse him of making his poetry "sound better than it really is", but the critics are usually poets themselves; and, invariably, the ones who resent or distrust Pi O’s performances the most are those poets who are either too shy or insecure about their own work to ever feel very comfortable or fortunate while standing behind a microphone. No wonder the sight and sound of Pi O enthusiastically shouting down the room aggravates the hell out of them; their poetry demands a more-considered anguish. And besides, Pi O gets all the attention!

This is not to say that a poet who feels awkward or out of place in front of an audience is a bad poet. Many a great writer has, on occasion, shrivelled up and died in the arse when placed under the glare of a spotlight. But one should not judge the poetry too harshly. A great poem badly read is still a great poem.

Conversely, the oral expression of a poem, performed in such a way that the full, dramatic import of its language is given voice, thus producing a heightening of emotional experience, does not necessarily mean that the text upon which that performance is based is lacking in power, craft or vision. The oral poem cannot out-do its written brother or sister; but it can, and should, live up to their expectations. The best poets, the true poets - and there aren’t many - have always been mindful of the fact that the full worth of a poem cannot, and should not, be judged solely on the evidence of its written form. Such a concept will find little enthusiasm among those university lecturers and academics who have built their careers on the basis that language is something that sits still. But language is never, finally, a static phenomenon, and those who know Pi O’s work and who have mastered the instrument that is the voice, and the difficult art of translating those black squiggles on the page into living and meaningful sounds, will understand how Pi O’s poetry transcends its written notation in much the same way that a piece of music transcends its score. There is a whole other thing going on when you read it aloud.

I remember, once, in the middle of a poetry reading at Eric Beach’s place, how Pi O made everyone stop and watch television - Elvis Presley's final concert. "It’s history! We’re watching history!", he said. Elvis had been one of his heroes, bigger even than Johnny Cash, so we were all terribly respectful. No one said a word. It was sad, watching "the King", 50 or 60 pounds overweight, forgetting the words to "Are You Lonesome Tonight".

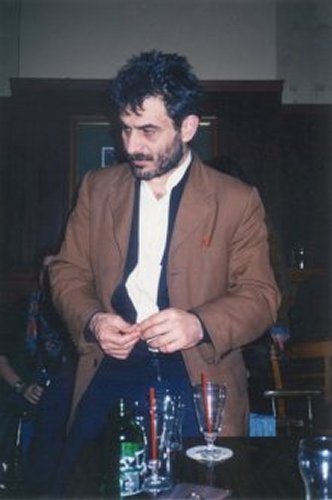

[Above] ΠO, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Ian McBryde, year unknown)

[Above] ΠO, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Ian McBryde, year unknown)

And there was Pi O. "Oh, my soul!" he exclaimed. To think it had come to this. You could see he was really affected by it. He couldn’t take his eyes off the set. Then there was that time when Pi O took me on a midnight tour of Fitzroy (Melbourne, Australia). We ended up outside the flats in Gertrude Street where his dad had owned a café in the 'fifties and 'sixties; where Pi O, himself, had worked and listened to the voices of the city that came in for coffee and cards. The way he talked about it, it was like he was still there, and it was all still happening. It was the voices, the yabba-yabba: the men in the back playing cards, the waitress on the phone talking to her lover. and then to her kid; the boss yelling at the kids on the street. The language with a swagger of Elvis would provide the basis for much of the poetry Pi O would later write and perform - a poetry that for some of us would transform that whole stretch of inner-city Melbourne real estate between the M6 freeway and Punt Road into sacred ground.

Pi O, the mythmaker, the storyteller, the carrier of voices. In 1977, Pi O and Eric Beach went crazy, doing more than two hundred and fifty poetry readings in one year. Mostly they read at venues in and around Melbourne, but now and then I’d organize readings for us in country towns, like Ballarat and Warrnambool. We always had a great time when we read in the country, especially Pi O. This was during the time he was writing what he referred to as his "ego-poems" ... a collection of mostly vernacular poetry that publicized Pi O as unabashedly "fantastic ... brilliant ... great! (no bullshit)." He was planning a large volume that he had decided to call The Pi-oems:

I remember trying to change a line from Shakespeare

so it didn’t look like Shakespeare’s

& using it in my poem.

I remember writing a "sonnet" that

rhymed like Shakespeare’s & hoping, no one knew it.

I remember putting my name at the bottom of a

Shakespeare, hoping that, Kris (he’s a critic) or someone

would hate it, so I could expose them.

No one noticed.

I remember, writing like Joe Brainard’s

'I remember' , & if anyone said: 'that’s like

joe whatshisname', I’d say: 'Hey!

I’ve never heard of him!' and look like a GENIUS!

Something was up. People in Australia didn't talk like this, certainly not in poetry. But there it was - the evidence: Pi O leaving small, square mirrors everywhere, "to surprise myself with my own image ... something to brighten up my day". "The greatest poet since the last one" was confiding in us. There was no stopping him. He kept mistaking himself for Brando and Gable, and yes, why lie about it?, his scrapbooks, by his own admission, were filled up with: "i'm brilliant. i'm fantastic. i'm great".

The very nature of the performance-poem-in-performance makes it difficult to tack down. In some essential way, each performance is unrepeatable. One always hears or "sees" something different. The language has a life of its own. It is free. It is dialogue - this aural interaction between poet and poem, poem and audience, audience and poet.

Unlike the page-poem, where one can glance ahead and see where the poem will end in another dozen lines or so, the oral poem exists in a kind of un-posted timelessness. Its life is always present tense. More's the pity, given the fact that there would appear to be a disinclination on the part of many critics, reviewers and academics to actually READ or HEAR Pi O's poetry in its completed (aural) form. Of course, they will read it silently to themselves, but that misses the point. Pi O's poems cry out to be given the vocal body that is their due. Silence is a luxury they cannot afford. To merely approximate the sounds intellectually, in one's head, without actually HEARING the poem is akin to humming the opening bars of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony in the simple-minded belief that this, somehow, approximates the experience of hearing it played at full volume by a symphony orchestra. It is the aural equivalent of blindness.

|

It is this oral "illiteracy" on the part of our critics and learned literary scholars that has conspired, more than anything else, to keep Pi O's poetry at arm's length, idling harmlessly on the margins of literary debate. I believe one could argue quite cogently that Pi O's poetry is, for all its skill in the handling of language and in its sheer innovativeness, the most under-represented and underrated work of genius in Australian letters today. Don't look for Pi O in the Penguin Book of Contemporary Australian Verse, or in the Oxford Book of Modern Australian Poetry, or in any number of other, so-called authoritative volumes. He ain't there. Nor are a lot of others who have been dubbed "performance poets", a tag which, it would seem, brands the work of these writers as highly suspicious or disreputable, as if performance had nothing to do with literature. Shakespeare would've loved that!

The best performance poets, the best oral poets, harbor a deep suspicion of the inordinate emphasis which teachers, English departments and universities place upon the idea of literacy, as if the ability to identify written words and their meanings, and to read these (usually silently, to oneself) is the only thing that stands between suffering humanity and a utopian condition usually reserved for eighteenth-century English idealists. |

[Above] Cover of 24 Hours by ΠO 2 (Artwork by artist unknown, year unknown)

From my own experiences as both a teacher and a poet I would say that the problem has as much to do with "oracy" as it does with literacy. There are students who can read an entire text without missing a word, but get them to read it aloud ... Where is the passion, the emotional strength, the eloquence, the involvement? The voice of literature in the mouths of most students (and, one suspects, in their heads!) is almost always in monotone, stilted, detached.

Pi O's poetry, and the poetry of the best oral poets, reminds us of the natural poetry that exists in everyday speech. It calls attention to the textures, tones and rhythms of voices which can - at times - transform the act of language from merely passing on or receiving information into a projection of one's own reality into the myth of the world. One reads Pi O's poetry as a kind of myth of himself and his own, psychical territory. Like a latter-day dreamtime legend, the poems take us on a timeless journey through the sacred sites of Fitzroy and Melbourne - the snooker rooms, the coffee houses, the street corners and souvlaki bars, where transformation is constantly occurring in the alchemical transactions of speech and human desire.

To dismiss Pi O as merely a performance poet is neither accurate nor even useful to an understanding of the nature of Pi O's contribution to poetry. There is no question he is the consummate performer - a poet whose work is frequently "published" by the voice directly to the ear - but he is also a poet who has struggled to define and refine the tools and materials of his craft. This is particularly evident in the scoring of his dialect poetry - vis: The Fitzroy Poems, as well as in the unpublished epic, 24-Hour Poem. If one reads Pi O aloud, paying attention to his notation, which incorporates a quasi-phonetic spelling of the language-as-spoken, one can read his texts in a voice much closer to the original than one would've ever imagined possible - migrant dialects, voices of men, women, talking in cafes, in late-night lounge rooms, over the phone; the business of being Greek, Turkish, ocker; of living outside the law; of being beaten or loved or forgotten. Somehow, the ear makes it all the more sensual and seductive:

him punch him

him punch him too

him hit him

him hit him 2, 3, 4,...

"Yoo no hit him!"

him hit

"Liv him alon wil-yum!"

him hit him more

"Eye punch yoo on noz!"

him punch him in stomaak

him kik him in lek

him skrech him in face

"Gon to Hospitaal!"

"Gon to Hospitaal!"

him en him

gon to Hospitaal.

Given the nature of the post-literate world, it isn't surprising that Pi O's poetry is often best appreciated and more likely to be understood in its oral manifestation. But one must not construe this appreciation as a criticism of the craft or power of the written scores he creates and employs. I like Pi O's poetry because of what it reveals about language (both oral and written) and how it behaves. In ΠO's poems one begins to sense the proportions of language and physical reality. As children we might have believed the world came first and that our language somehow grew out of our experiences of the world. In Pi O's cosmology, one begins to see (and hear) "the world" as a complex translation of the inner life of language.

|

The poem is composed of two, simple Chinese characters. The upright rectangle divided by a line which signifies the sun, and the character "?" which signifies mountain. Using these two symbols, ΠO creates a sign for something that is, literally, not present in either. The relationship of the two ideograms, nevertheless, infers an unstated quality, a quality which transcends the "facts" of sun and mountain. Pound called these qualities "Luminous Details". |

[Above] Title Unknown 1 (Artwork by Pio, year unknown)

They were attained by a sudden translation of the visible, thus affording an unobvious vantage point from which one might apprehend the invisible. An example of Pound’s notion of "building light".

Here, in Pi O's "concrete" poem, even though the denotative symbol is missing, we are still able to recognize the quality of "reflection in water". The reader (or perceiver) makes this imaginative leap when the unstated reality is grasped, and the perceiver enters wholly into the creative act, becoming as it were, a co-creator in the realization of the poem. This is possible because the poem echoes (visually!) the kind of conceptual patterning evidenced in human consciousness. It mirrors (ironically, in this case) the fundamental relation-making facility of the mind. The poet has left room for us to participate, and the participation re-creates a sense of the discovery that the poet experienced himself in the act of creation.

Consider the following concrete poem:

[Above] Title Unknown 2 (Artwork by ΠO, year unknown)

Superficially, this piece of visual understatement has no meaning. One can gaze at it for months, years even, and not understand the what or the why. Yet, it succeeds as a concrete poem to the extent that it reveals to us something about the nature of perception, and how what we are looking at is very often a product of what we expect to see, rather than what is actually in front of our eyes.

In this case, we look at the puzzle - a crossword puzzle - which is familiar to everyone. Usually, it is the blank squares that give the puzzle its meaning. It is the blank squares and what we might fit in to them, that make it a puzzle. But here, Pi O (or ΠO as he prefers it to be spelled) has turned everything on its head. The puzzle appears simply nonsensical. Where are the clues? "Across" and "Down" are missing. One has to look at the puzzle in a way that one has never looked at a crossword puzzle before, engaging it on its own terms, otherwise one misses the entire meaning. Only when one steps outside the habits of one's perceptive routine is there the possibility of seeing what is there, and feeling, again, the same sense of joy and empowerment that occasions every act of creation.

The meaning of the "poem" stares back at us from the page, ironically underlining the nature of false assumptions, urging an imaginative leap. In this case it is the black squares which provide the key. The meaning of HIP / WHITE / SEXUAL / LIBERATION / FUCK! resides in the composition of the negative space – information where it is least expected, where one would not usually seek it or find it.

ΠO's concrete poems offer simple, schematic metaphors for structures of thought and symbolic representation. They provide graphic examples of the sorts of conceptual building blocks with which he constructs all of his poetry. ΠO's manipulations of word/symbols and his skill in wringing (or finding) profundity from (and in) the most obvious places is very well demonstrated in the following:

[Above] Title Unknown 3 (Artwork by ΠO, year unknown)

An image or idea (a "vortex" as Pound referred to it) is a bundle of energy - mental energy, emotional energy - "drawing in whatever comes near to it". It has associates. It has a history. Here, we have two words whose typography and spatial relationship affect the way in which we "see" what they can mean. Noun and verb intermingle in our minds. To use one of Buckminster Fuller's metaphors, it is as if they are tying a kind of knot. One might even call it a philosophical knot, but it is a knot all the same. A self-interfering pattern. A tension. Attention. And it creates energy.

What is the relationship of "FISH" to "fishing"? How is the action related to the object of that action? The potency of the poem - any poem - is the insight it induces. What we have here is a deceptively simple vortex "from which, through which and into which ideas are constantly rushing". What ideas you ask? The mental shape of the imagination goads us into action. FISH is the most significant fact about the act of fishing. Not only the reality of it, but its thought-form: the archetypal FISH. One could go on forever, listing the various images and ideas that are suggested by this configuration, by this simple knot of noun and verb, this interplay, this vortex which creates energy out of its own stillness. The poem, itself, might be trivial, but what it tells us about the way in which we humans make and assign meanings is strikingly profound.

Most of ΠO’s concrete poems are engagingly humorous. They are predicated on play - word play, sound play, image play. Silent "performance poems" in which the type and page are themselves the performers ... though there are some concrete poets - such as Jas H. Duke, Peter Murphy and ΠO, himself - who have managed to construct "oral" concretes which work with equal success on the page and on the stage. ΠO's "laundry blues", from his book, Street Singe, is a case in point.

In the following concrete poem, ΠO once again makes use of the Chinese ideogram (in silent homage to Pound and Fenollosa) creating a visual pun which - if it is apprehended - leaves the impression of being as much the perceiver's creation as it is the poet’s:

[Above] Title Unknown 4 (Artwork by ΠO, year unknown)

The poem employs the Chinese ideogram that signifies "lewd". ΠO inserts this complex character as a letter. One can play around with the image of the ideogram, itself, and its etymology with interesting (and often startling) results. Even for those who haven't yet been initiated into the subtleties of written Chinese, ΠO’s poem still works its magic. ΠO’s poetry is at its best when it implies connections among thoughts and images when the connections are not obvious, or where they do not exist at all. Looked at critically, his work calls attention to the imaginative facility of the self-creating ego by which the human being renders the experience of chaos meaningful. ΠO's "self-interfering patterns" bracket our experiences of the images and entities that live within the poem in such a way that we are encouraged or duped into making the connections ourselves. The plausibility factor is temporarily extinguished under the weight of ΠO’s careful manipulation of syntax, space and symbol. Suddenly, surrealism is no longer an external event but an inner process which we have created out of our relationship with the poem. The best performance poetry does this. The best poetry does this. Poetry does this. By definition it is a high-energy construct of self-interfering patterns (The Pound Era, Hugh Kenner) which illuminates the invisible. To be in the world, is to be constantly in a poem. To enter into one of ΠO’s poems is to enter a world not only of his making, but of ours as well. ΠO’s "Everything Poem" - which is (currently) in three parts, and ever-expanding - offers the clearest example of the alchemical nature of ΠO’s ideogramatic montage technique. Superficially, each of the three parts of the poem appears to be nothing more than a collection of random information. Bits of trivia, statistics, quotes, all conspire to suggest a world gone mad, a world where chaos reigns. In "Everything Poem, Pt III", ΠO tells us:

if

2 lines

on a "graph"

cross

it must be

important

so

comb your

"Hair"

*******

A

walnut

is

a "family" problem

and

a towel

is a

"mild"

disease.

*******

It

takes

a long time

to understand

“Nothing!

(I

don’t care

if it

looks

"complicated"

I want to

be understood :

Now! (:not

after)

when

everyone’s

gone :

"Now!:"

(Adverb,

conjunction,

... and

Noun!)

I

want to

be

able to "speak"

and

speakandspeakandspeakandspeak

andspeakandspeakandspeak

andspeak

andspeakandspeakandspeak

andspeak

and

not worry about

(whether or not) I’m playing

with the

"net

down"!

Here, we have a highly energetic rush of ideas, images, sounds and proclamations, as if ΠO is engaged in the exposition of a complicated hypothesis. At once passionate, confident and exact in his use of details, he deliberately withholds - as if it is too obvious to state - the significant point, the underlying theme, the central idea. Pound did the same thing nearly a century earlier when he composed "In A Station of the Metro":

The apparition of these faces in the crowd

Petals on a wet, black bough

Like Pound, ΠO would persuade us to his point of view by the sheer ingenuity of the comparisons he implies. But what is ΠO’s point? What exactly is he trying to prove? What does combing my hair have to do with the intersection of two planes? And how is a "walnut" a family problem? ΠO doesn't ask us. He tells us. And before we have time to question what he has said, he is already assuring us that a towel is a "mild" disease. Like the frames of a film, sped up to approximate movement, ΠO’s images slip past our eyes and ears at the speed of thought, setting up a chain of expectations and surreal associations, tying a series of philosophical and psychological knots in much the same way we have seen in his "concretes".

But the verses present much more complex vortices than what we find in the visual poems. This is not space-art, but time-art. One listens to ΠO’s poetry as one might listen to a play - the language is dramatic, confrontational. In other places, it seems to take on the characteristics of a logical argument where the syllogism leads inexorably to its conclusion. Except there is no conclusion, no valid inference, apart from what we, the reader/listener are prepared to ignore, or admit or invent, making our own sense out of what the poet tells us; already finding ourselves happily assenting to the fact (with good reason) that "it takes a long time to understand 'nothing'". And no, he's not taking the piss; and it's no joke - this is no con - he's not playing around with us, 'cos, after all, he's already told us - "in no uncertain terms" - that he "wants to be understood : Now! (:not after) when everyone's gone...".

When one turns to ΠO’s dialect poetry - particularly the poetry contained in his epic 24-HOUR POEM, one appears to be confronted with slices of social realism. ΠO, himself, has at times described himself as a social realist. One could describe the Soviet filmmaker, Sergei Eisenstein, in the same terms. But the tag doesn't do justice to the vision of either man. Eisenstein's montage style is the cinema equivalent of Pound's ideogrammatic method and both are combined in the poetry of ΠO, as if one is watching a poem and reading a movie all at the same time. Again, one must put one’s tongue to the task:

Over

at one of the tables Darko

is trying to teach a Greek kid: Yugoslav.

Dirty words first:

Yedi–gonna

eat shit

Boodalla

idiot

Kot-e-yeb-e

who gives a fuck

Yeb-e-s-e

fuck you

and so on.

‘This-

World isn't going ta

make it.

It isn't going ta make it!

That's what

keeps going thru my head’ Charmaine sez

‘It isn't going ta

make it’

A bloke

stoned off his tree

drops a 20c

piece

into the pinball machine

and stares

at it.

He doesn’t know what to do next:

PRESS THA BUTTON

PRESS THA BUTTON!

It

isn’t nice

calling

a bloke an imbicile

Steve sez.

How can you call a bloke, that?

You're a sick bloke mate.

A sick bloke.

He calls the bloke an imbicile

and then asks him if he's alright!

Who's he calling an imbicile?

I told im:

It's a strong word mate

/learn about it.

Call a Cop an imbicile

and he'll

knock ya out

mate!

One doesn't need to be told where one is. It certainly isn't a library or a park. One can sense the underlying threat of violence, the aggressiveness of urban life, the press and pressures of the city, the congestion of the cafe, as we cut (cinematically) from one shot to the next. It is almost too stark to be social realist. The furniture here, the props, the costumes, the comment, is all in the talking - a landscape of voices, a folkloric of speech.

|

One is reminded of T.S. Eliot's gossiping women in "A Game of Chess" from The Wasteland "If you don't like it you can get on with it, I said./Others can pick and choose if you can't./But if Albert makes off, it won't be for lack of telling./ You ought to be ashamed, I said, to look so antique./(And her only thirty-one.)/I can't help it, she said, pulling a long face,/It's them pills I took, to bring it off, she said ..." , etc.

Just as Eliot's women offer evidence for the failure of love in modern society, so do the characters who inhabit ΠO’s poems attest to the fragmentary nature of experience. These are not complete pictures. One zooms in, then cuts. Fade up. Fade Out. Dissolve. The characters, like the language, are always moving. Ideas slip in and out, hardly recognized, but somehow felt, bodily, as one does when one listens to a conversation while one is thinking of something else. One scene gives way to the next. This one in close-up, that one in wide-shot. The camera directions are implied by the language of the poem, in the same way that Shakespeare creates a "close-up" (psychologically) when he temporarily drops the English and has Caesar say: "Et tu, Brute!" |

[Above] Photo of ΠO by Pamela Sidney, 1989.

ΠO is a poet who takes language seriously. All language. He understands how it can conceal as much - nay, more! - than it reveals; a poet who obviously distrusts the speech of academia, the learnéd, the well heeled. A more "educated" man, distrusting ΠO’s poetics, might think all one had to do was sit in a cafe with a tape recorded plugged in, recording everything that was said. Then it really would be social realism. Such oral histories serve their purpose, but they produce a Studs Terkel, not a ΠO.

In the same way that any good writer will pay careful attention to the construction of a sentence, refining the syntax so that it corresponds to the exact shade or color of his/her meaning, so ΠO creates a syntax of images (a grammar of images) in which each image functions, metaphorically, as a part of speech - here a noun, there a verb, everywhere a predicate. Image upon image, sound upon sound, rearranging the terrain of the ever-expanding, ever-contracting poem. Like the kinship system of the Pintupi people of Central Australia, where two men, taken separately, are seen as possessing two, different "skin-names" (sub-section designations), but when sitting down together, in relationship, are known, collectively, by another name altogether, a name which signifies the separate and unique personality that is formed and takes its life from the interaction of both.

ΠO’s "arguments" are symbolic and illustrative of the underlying chaos of the unconscious, but their real, poetic power lies in how they encourage and goad the reader/listener to see, hear, feel and understand how the conscious mind rallies to bestow order on grunting humanity, and to appreciate how the grunts themselves (read: language) impose their own order (aesthetic, ethical and metaphysical) upon our perceptions of the world. The double-barrelledness of existence.

Poetic experience, like all experience, is double-barrelled. It is an appreciation as well as an expression. One speaks and one listens; one hears and one speaks. To experience ΠO's poetry is to understand that the speaking and the listening are one. It is ourselves invading ourselves, with images, with sounds. The sounds themselves have magnitude. Are of the body, the breath, the life-force. "Say it out loud," ΠO exclaims to his detractors when they confess they can see no meaning in what he writes. "Read it aloud!"

Published in Suite101.com (Australia)

About the Writer Billy Marshall-Stoneking

|

Billy Marshall-Stoneking has been living and working in Australia since the early 70s. In the 1980s, he edited The Stories of Obed Raggett, the first collection of original stories written by an Aboriginal writer in his own language (published bi-lingually in Pintupi/English parallel text). In 1991, he co-wrote and staged the first-ever poet-written, poet-acted and produced, verse play, Call It Poetry/Tonight, at the Sydney Theatre Company's Studio Theatre at the Wharf, that was subsequently aired on Australian national television. Billy's first, full-length dramatic play, Sixteen Words For Water was published by Harper/Collins in 1991. Much of Billy's work has been influenced by his long association with tribal Aboriginal people. He is conversant in several Aboriginal dialects, and his film documentaries - Desert Stories, Nosepeg's Movie and Pride & Prejudice draw heavily on his time spent in the desert. Among his many script-editing credits is the Australian film, Chopper. Currently, he is head of the MA writing programme at the Australian, Film, Television and Radio School in Sydney. |

[Above] Photo of Billy Marshall-Stoneking by Billy Marshall-Stoneking, 2000.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.6 (September, 2002) |