NORTHERN TERRITORY POETRY - THREE DEGREES OF SEPARATION

By Marian Devitt

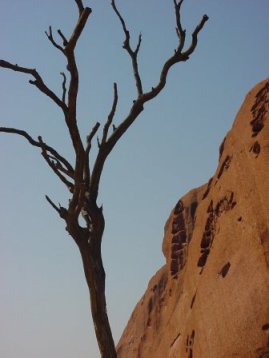

[Above] Watarrka #3, Watarrka National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

Many Australian poets have travelled to the Northern Territory, (Mark O'Connor, John Anderson and Coral Hull among many others), in the last decade, inspired by the landscape and cultural differences. Significant poetic works have resulted from these journeys and have bought to a wider reading public something of the experience of the physical reality of the Northern Territory. However not many Northern Territory poets, who live here on a permanent basis, have come to the attention of the 'mainstream' of Australian poetry, a recent exception being Lee Cataldi (who now lives elsewhere) with her collection Women Who Live On The Ground, which is irrevocably connected with the Territory.

If there are any appreciable differences between the works of visiting and 'local' poets I would have to say that one of the defining characteristics of poetry written about the Territory by Territory poets is that of intimacy and that this quality of intimacy reveals relationships that have been established through a sustained engagement with landscape, people, and cultures. It is an intimacy that reaches beyond observation and recording and a sense of passing through, to engagement and identification on a deeply personal level, although the poetry is often outward-looking as poets attempt to integrate personal experience with their environmental and cultural context.

Intimacy is at the heart of this poetry because the relationships of the poets to environment, people and poetry has grown over time and often in uniquely privileged circumstances. Many NT poets have had legitimate engagement with extraordinary circumstances, cultures and environments through their work circumstances and choices of abode - circumstances which may seem commonplace and ordinary to those living in the NT, but still seem exotic and 'unknown' for people from more urbanised or cultivated environments.

The degree of intimacy with the Northern Territory landscape often correlates to the degree of isolation that is experienced. However it is significant that, for many Northern Territory poets, landscape alone is not their subject matter and what is critical in their response to the landscape is their relationship to the people within that landscape. There is an acceptance of the inextricable.

|

The context within which people live is appreciably different to the Eastern seaboard settlements of Australia and this context is an important consideration in appreciating the poetry of the region. The poets featured in this article (a very limited sample of the various works and poetic styles being developed in the NT) need to be read in context.

There is a limited tradition of printed works of poetry in the Northern Territory and not many records of the ways that individual poets have developed.

However in the last ten years some considerable efforts to identify and support the literary community have resulted in more focus by the poets themselves on who their regional contemporaries are and, for those concerned with writing about the environment, a growing confidence that they fit into a broader nexus of poets concerned with landscape and environment. In the last five years, an increasing number of NT poets have been published by Australian and international literary journals. |

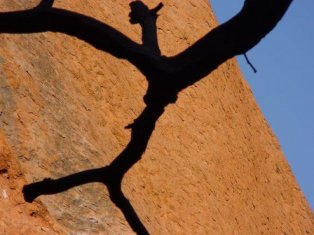

[Above] Uluru #16, Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

For many who come from highly urbanised environments, places like Darwin and Alice Springs, despite all their modern conveniences and comforts, are still a shock. Darwin's tradition of rebuilding itself after cyclones has resulted in a brash, optimistic facade of modern, block architecture, embellished with the cosmetic application of designer corrugated iron and the opulent growth of tropical gardens. There is evidence everywhere of urban development that constantly anticipates a population boom that has yet to happen and a growing urban sophistication in the services available, although it is still an expensive place that sharply delineates between socioeconomic groups.

The Territory is the home of matters of national significance such as uranium mining in World Heritage Areas and the application of Land Rights legislation. Criminal justice issues, such as mandatory sentencing, are hotly debated locally and in the national arena while in recent years controversial euthanasia legislation was formulated and enacted in the Territory and then dismantled by Federal Government opposition. The Territory has had the same government for over twenty years and many, whether supporters of this government or not, view as interference, the attempts by 'outsiders' to moderate or dissolve legislation that has been developed in response to the social and economic conditions of the Territory.

The Territory is home to traditional Indigenous cultures and their achievements and dilemmas. It is now also home to many generations of Greek and Chinese settlers in Darwin, Chinese in Pine Creek and descendants of Afghan camel traders in the Centre. The regional centres of Jabiru, Nhulunbuy, Katherine, Tennant Creek and Alice Springs each entertain their own particular cultures and cultural mixes. The tiny community of Nhulunbuy, centred around a bauxite mine and within close proximity to the traditional Aboriginal community of Yirrkala, has alone been home to members of up to fifty ethnic groups. With a population of less than 200,000 in the whole NT, it is worth noting that some municipal shires in Sydney have far greater numbers than this. In recent decades the Indian, Pakistani, Indonesian, Filipino and East Timorese populations have increased and are now established elements of the multicultural mix. There has also been, over the years, a significant amount of intermarriage with local Aboriginal people.

The population has layers of transience - from retirees escaping a southern Winter to protesters and activists mobilised by the cultural and environmental issues played out in this highly politicised environment. There are others who relocate from urban and rural recession hoping to secure regular employment, only to find that here, opportunity is ruled by the violent extremes of the weather and the vagaries of development. There is an increasingly less transient echelon of government workers, renewing contracts as transfer opportunities down South dry up, slowly improving their lifestyles with the addition of more air conditioners. It is possible in Darwin, or any of the major centres, to live an entirely air conditioned life, barring sorties from car to office to home, eschewing altogether any engagement with the environment or the Indigenous population. However, most people do enjoy the outdoor pleasures of the famed Dry Season as well as the economic benefits of the annual influx of tourists and, for some, the benefits of a highly subsidised lifestyle.

Further afield, beyond the enclaves created for its Public Servants and entrepreneurs in Darwin and the major regional centres, the land reclaims any sense of civilisation or comfort. It is a harsh, dangerous and unrelenting environment, extreme in every way, but more subtle and delicate than we are initially led to believe. The environment regularly repels its population through flood, fire, cyclone and various other natural disasters. The coastline is difficult to monitor and any tension with our South East Asian neighbours is felt keenly in the military presence and sorties across the Arafura Sea. The weather is as complex and subtle as the transactional climate although the local media revels in sensationalist responses to the natural elements.

In remote circumstances people endure each other as a necessary practicality of remote life. Remote communities are peopled with many representatives of elite disciplines - anthropology, science, the legal professions and medicine-providing services for an Indigenous population living in what has been described as Fourth World poverty, where resources are wasted and European models of management are inappropriate, ineffectual and essentially misunderstood.

A remote community eventually reduces everyone to size. Living in a remote area has everything to do with self-sufficiency, acceptance and co-operation and the ability to cope with extremes. In the worst and most frequent scenarios, life in a remote area results in the antithesis of these things. The capacity to endure has a great deal to do with personal politics, philosophies, beliefs and at times, basic cunning.

[Above Left] Mitchell Grass, Watarrka National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000) [Above Right] Ochre Pits, West MacDonnell National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

For the 'expatriates', living such an extreme, remote life tends to bring out the best and worst in everyone, but in a situation where people are 'contracted' to come in and perform a particular job it is more often the case that people simply leave after relatively short periods, no longer able to sustain themselves in an environment fraught with conflict, lack of conveniences and limited possibilities for reasonable relationships. There is the ever-present and disorienting experience of culture shock in your own country. The Territory is a highly mobile environment with a long tradition of relocation, transfer, attempts to leave and sometimes, reluctant returns. Often periods of isolation and intense engagement with remote communities are relieved by relocation back to an urban centre, although this relocation is as fraught with stress and disorientation as the original remote posting.

It is in this varied context that poets find the substance of their work. The work of our local poets reveals the complexities and the subtleties of this environment and provides greater insight into the dual forces of repulsion and attraction that the Northern Territory exudes like a magnetic field. Their work is intensely personal, imbued with an intimacy, perceptiveness and depth of experience that is not possible to achieve by passing through like an early explorer on a reconnaissance trip.

Intimacy comes from intense engagement and this requires a significant period of time committed to place, people and the environment. With the degrees of transience, there are also gradations of acceptance by the people who have always lived here. It is possible to live here and never meet someone born in the NT, or even someone who has been here for more than a few years, but after a watershed period it does seem that another layer of Indigenous, European and Asian history and connectedness is exposed, much as layers of dirt are scraped from the earth in bauxite mining. Some with generational 'kudos' tend to look askance at those who stay a mere five or ten years as hardly worth getting to know. Stay more than ten years, make a contribution to the place and the levels of acceptance and engagement begin to shift. It is then possible to experience the phenomena of living in extreme isolation in a remote community for several years yet somehow establishing a web of acquaintances and connections throughout the whole Territory - connections that permeate and infiltrate many cultural groups and communities. It is a place that accepts you when you have done your time. The notion of six degree of separation between people seems to be reduced to as little as three degrees of separation in this sparsely populated environment.

This is an environment where people and relationships cannot be excluded from landscape. It is not possible to write simply about animals or country distinct from their cultural, totemic or historical significance and capture the genuine experience of living in the Territory. The poetry currently being written here generates from these extremes and complexities.

|

Kaye Aldenhoven has lived and worked in many remote communities in the Northern Territory. She is currently working on a collection of poems begun when she worked as a teacher in Jabiru. The work has continued since relocating to Darwin in collaboration with the artist Jane Miles. The work charts Aldenhoven's experience of living for many years in Kakadu National Park. Jabiru is a highly subsidised and bureaucratised environment with the main tension existing between the challenge of managing Ranger Uranium Mine within the World Heritage listed Kakadu National Park. The local people, the Mirrar, Gagadju and Gunjeibmi clans are involved, with varying degrees of access and success, with the management of these concerns. |

[Above] Torrens Strait Island Pigeon, Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

In this context Aldenhoven has written about the juxtaposition of urban and wilderness environments, about a town that Aldenhoven describes as a "donut hole in the Park, and the incompatible sensitivities of conservation with a massive annual influx of tourists making their pilgrimage to Kakadu, the uranium mine which is releasing treated water into the floodplain of the Magela Creek and the locals ... Suburbia and wilderness only mesh/engage at the very edges, where there is an uneasy meeting, a staring at each other." Aldenhoven writes from a perspective of privilege in that she had, at the time, a justified reason and purpose in being posted to this extraordinary and unique landscape.

Night Walk with Dingo

Who can concentrate on the inner self

in the midst of household busyness?

Escaped from my mould skinned walls

the wet season night looms closer,

more intense, than the news reporter,

touting war and famine.

I have just switched out of my life.

Lightning flicks across the sky,

a storm too distant for thunder.

In the calm before the wind

the hot wax smell of flowering speargrass

sweetens the thick air

reminds me of my friend who never ironed

but remembered the smell anyway.

Disturbed by my passing

the red necked lorikeets in the town centre

chitter-chatter above me.

They are first out in the morning,

last back from the bush every evening,

like kids never wanting the day to end.

Perched on the 60km sign

near the hotel

a barking owl returns my barefaced stare,

ignoring briefly her mate's warning call soft from the dark.

Along the warm bitumen I lengthen my stride

the tar a shining river running blackly through the night

my feet skim the surface on space-age running shoes.

Behind me

the precise click of dingo claws.

I turn to confront ...

the dingo holds my eyes with her own.

She stands to watch from a pool of streetlight

a golden dog, in yellow light,

and as I watch blinkless, she disappears

into the yellow grass.

The females are more cautious than the males.

In their first year the pups, schooled by their mothers,

are seldom seen in this mining town.

Timid and hungry they lurk on the edges.

The adults are silent opportunists,

thriving on the leavings of suburban families,

the scrapings from tourists' plates at the hotel,

and the bins at school.

Bold as brass they stare at the lighted windows of kitchens,

inhale the scent of night shift suppers,

confident of their apparent invisibility.

They avoid dogs of the domestic strain,

sidestep night vehicles and walkers,

merge into the speargrass

like sleight of hand.

Arrogant and powerful,

it's not easy to stare them down.

[Above] Dingo, Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

Aldenhoven is unashamedly erotic in her response to the landscape, an eroticism imbued with a sense of expectation and anticipation, of knowing the environment so intimately she anticipates the climax of the seasons, the release of tension that dominates before the rains.

If you were here I'd make love to you

The coming down of the Magela

after the first storms,

we chased that front of water all day.

It surged slowly,

calm in the surety of its fulfilment

trickling unevenly into dry spaces

filling hollows, spilling, collecting

pushing the debris of the Dry before it.

The dry leaves crackled,

The hot sand gasped,

giggles of bubbles escaped

as the water soaked deeper.

Beetles dragged their sodden carapaces

onto the island havens of your legs

the swirling froth tickled your skin

you laughed and rolled in the rolling flood.

The swell of water

gouged the sand from under your hips

rolled you roughly along

dragging you underneath the paperbarks

the luscious wet warm

tangle of sand and water and your hair

your grazed knees.

In the stone country

a taut pod explodes, kapok floats

Kingfisher dips into dark pool

the coconut smell of rock fig

Yamitj calls out from the escarpment

yams grow

the waterfall drops, stops, falls again

Black Walleroo leaps the gap.

Laughing

sucking mango juice

the smell of pandanus fruit

the gurgling cackle of a Koel

pursued by her male

golden-eyed frogs on lily leaves

lure an iridescent water python

flying foxes vibrate

then fold their silky wings

A thousand whistle ducks lift and turn.

If you were here I'd make love to you.

[Above Left] Midden, Charles Darwin National Park, Darwin, Northern Territory Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001) [Above Right] Mangroves #4, Charles Darwin National Park, Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

The privilege of close relationship is evident in Aldenhoven's poem about a trip to Ungbarrbarr on the Coburg Peninsula, although her own assessment contemplates a distance that is unbreachable: "The poem speaks of the many generations of relatives who are interred through bone burials in rock shelters. Perhaps it hints at the impact of colonisation. I think the last stanzas illustrate aspects of relationship with land that Balandas [European people] do not have, even though we love the landscape."

In My Husband's Country

We camped in an open place

Near a clear spring

In Ulbu country

At Ungarrbarr.

In July we sat by the night fire

As the cold seeped into our bones

In the moonshadow

Of those Two Brothers

Who changed to hills in the Dreamtime.

Here the Rainbow Snake

Put himself on the sandstone

Red-ochred giant across the cave ceiling

To guard dillybags

Stuffed with the bones

Of my husband's people.

As the cool wind

Flowed down the escarpment

Old Man called out

Clear in clear night

Called out to those stone-country spirits,

As we listened to them

Moving quietly

Over the stone terraces.

Telling those Wardejaname,

Those stone-country Wardejaname

Who we are . . .

Good women,

New to this country

Telling us

Wardejaname, him friendly.

Wardejaname, him listening now.

Spirits belong rocks,

Live in rock,

Play music in rock.

Wardejaname,

Him like us now.

You look his country

You look his painting

Him happy.

We camped in an open place

Sleeping by the night fire.

Our credentials exchanged

We could begin our business.

The use Aldenhoven makes of Aboriginal English is a natural outcome her 'skin' credentials with her 'husband' of the poem, a relationship full of implications of sharing and learning from each other, regarded seriously and honourably by both. It is not unusual for Northern Territory Balanda to engage in Aboriginal English with Indigenous people as a legitimate language of communication, without the hesitancy some less familiar and connected by skin relationships might feel.

Aldenhoven explores the idea of 'the landscape of the senses overlying the spiritual landscape' in the poem -

The moon is full and evil spirits can see their own shadows

[Dird nayuihmi narmande gabarriwoyiknarren* ]

The yellow moon slides

behind the trees

searching

searching

among the eucalypts

for Narmande, wicked Narmande.

But they hide.

Between the satin-barked trunks

silently glide

cunningly merge

their evil shadows

with the scented shadows

of the gums.

|

Invisible

for the gasp of time

between moonset and sunrise,

shades

becoming themselves.

They extend their shadow play,

dangerously linger,

dabble long toes in lank grass

inhale sadly the watery air

trapped between the canopy of leaves

and dew point death.

Shades!Become invisible,

Before the sun flames you.

Wincing,

cringing with the pain of light

they flee.

They insert their brittle bodies

slivers of spirit flesh

and elegant bone

into the rock slits

of the escarpment.

Only the pursuing wind

hunting their limbs

through the gorges

hears their thin cries

and understands their longing

for substance.

*Mayali/English. Nick Evans 1991 |

[Above Left] Dragon #3, Serpentine Gorge, West MacDonnell National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000) [Below Left] Desert Rose, Watarrka National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

Kaye explains further "I am interested very much in the landscape of the senses ... the smells, the textures and weights, who was sharing the country with me at this time ... Another layer of meaning for me is intellectual understandings, both of the prehistory, the dreaming stories, the aboriginal and western scientific notions that make the landscape intensely meaningful to me. In the same way that Bill [Niedjie] can talk and does, of his travels over the land, so my own family and I have our own memories and knowledge which enrich our experiences of Kakadu and make the landscape emotionally and spiritually powerful."

A further step away physically, but still very much centred in the Northern region is the poem Sumatra - Lake Meninjau. It is important to note that the sense of region in the north extends as far as North Queensland and northern Western Australia, Indonesia, East Timor and Papua New Guinea in the consciousness of people who live in the Top End. Again the erotic prevails in Aldenhoven's response along with the duality of familiarity and strangeness. As the poet says, "The physical and cultural landscape of Indonesia is a wonderful paradox for us in North Australia, so close in kilometres, and so connected geographically and historically and throughout prehistory, but delightfully different - as Lee Cataldi said: [it is possible to see] the known in the unknown."

SUMATRA - Lake Meninjau

Path

Steep steep

Zigzag

Path

Winding down the ancient caldera

Narrow one-foot path.

Down through the dense rainforest

Dark, shadowed, cool.

Whoops of unseen monkeys

Bounce high overhead.

Climbing down

We pass children and grandmothers

Climbing to market,

Climbing up to market

On the rim of the sunrise

Balanced on their heads

Baskets of produce

Rise towards us like offerings,

Morning offerings for the temple gods.

Arrangements of papaya, limes

Arrays of ginger, chili, cloves

Curls of cinnamon bark, cardamom

And pyramids of temple flowers

Rise vertically towards us

On the way to market.

Climbing down

Vivid fern fronds

Tickle our legs.

Tumescent red fungi,

And purple butterflies

Flower on the cool floor

Of the forest.

Descending

We arrive at a party

Of laughing men and women

Gathering night-fallen fruit,

Harvesting the spiky maces of durian,

King of fruits.

"Do you like durian? " a man sings out.

"Ja, saya mau durian," I laugh back.

Emerging from the trees

He cleaves a durian

And offers me

His fruit.

"Do you know what we say? About durian?" he asks.

"Durian is good for women.

When the durians come down

The sarongs go up."

From his gift

I extract the smooth segment

From its silken cell,

And suck the creamy flesh.

"Do you like durian?" I ask.

"Ja."

Climbing down the ancient caldera

Trickles of sweat

Caress my back.

The poetry of Prithvindra Chakravarti, a Bengali Indian who spent many years working in Papua New Guinea before relocating to the Northern Territory in the 1970's, has a similar sensuality and sense of intimacy. The poem "Mosquito" is firmly centred in the often tormenting reality of living in a tropical environment. The personification of an insect is a fitting way to transmit the sense that one must come to terms with every element of the environment, at a very personal and basic level.

Mosquito

In the afternoon

She walks, wanders, comes and plays

Sits on my lap, hangs on my shoulder

Covers my neck with kisses;

Places her nose on my cheek

Presses and rubs it

Lovingly.

In the evening

She sings songs, dances wildly;

Engraves her name with teeth

Scratches and burns my cheeks;

Reaches for my waist with her fingers

Slackens and unties my robe

Silently.

In the night

She comes in a swarm, submerges me

And digs a canal with her picks and axes;

The fleet of boats rides on the low tide

And the heavy sediment of salt only sharpens

My anguish and my fever

Incessantly.

Chakravarti's work focuses on the incessant other life that continues despite the generations of settlement and civilisation. One has only to leave a place abandoned for a short period of time in this environment for the space to be reclaimed by the natural elements. There is a sense then, in this particular reality, that life here is somewhat more balanced and in perspective, in that the man-made cannot possibly dominate over powerful elements such as the cycle of insects, cycles of death and decay, destruction and regeneration.

[Above] White Gum #3, Watarrka National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

Ants

Bits of flesh in their mouths

Cheering and thrilling

They are running, shoulder to shoulder

In rows, in lines, searching peelpeel peelpeel

Crossing verandah

Climbing up walls

Towards an unknown tunnel

in rows, in lines, marching peelpeel peelpeel

A crow died yesterday

No trace of it is left now

And crows have gathered from ten countries

In rows, in lines, marching peelpeel peelpeel

Draught blown by wings

Kahkah kahkah by the drumming beaks

And lumps in their mouths

In rows, in lines, marching peelpeel peelpeel

They are running in an unending flow

Cheering and thrilling

A battalion of ants

In rows, in lines, marching peelpeel peelpeel ...

The intensely personal nature of the relationship with the landscape and its creatures is evident in "The Jintipirri and I". In this poem there is an almost erotic pursuit of the bird. The poet is himself transformed by the interaction with the jintipitti, becoming birdlike himself by the end of the poem, 'perching firm' on his verandah where he cares of the 'knotted world' seem to have dissolved.

The Jintipirri and I

The little jintipirri

shrugged off the dew

While pacing up and down

in my moist intimate yard

she shook off the rest

from her dishevelled feathers.

I knew instantly

what was awaiting me

this day

in the knotted world.

She paused,

wagged her tail,

pecked at tidbits

and poured her warmth

profusely

- the giggling buoyant figurines,

the intricate handiwork,

the wriggling plaited shadows,

drowning the whole surface.

Unmoved

I overtook her.

She flew desperately to a poinciana

near the edge

washed in the dawn's cool glow

- her amber eyes

gazing at the far horizon,

her chattering mouth

cracking riddles.

Standing still

I simply startled her

with my piercing silence.

Flapping the motiffed wings

vigorously

she took off

for the last time

carving a crescent in the air

to reap a glorious bloom

and sat at ease

on the crest

of a lightning-struck palm tree

by the creek.

But I

perching form

on the verandah of my cottage

outmaneuvred her again

by prevailing upon the immense expanse

she wove around her

so diligently

*jintipirri is willy wagtail in Warumungu - a central Australian language in the Tennant Creek region.

|

Another aspect of privilege is the often close and enduring relationships that are possible between white people and Indigenous people in the Northern Territory. There is often an assumption by 'southerners' that the general atmosphere of the Northern Territory is one of racial discord or repression ... the North as an inverted 'Deep South'.

The reality is that, while discord and dysfunction are by no means absent, there are many examples of relationships that are the building blocks of reconciliation and have been now for many generations. This is despite the cultural misunderstandings, the different values and perspectives and ongoing language difficulties.

Meg Mooney, from Alice Springs, says, "Being close to Aboriginal people is, for me, a major bonus of life in Central Australia. I try to write about Aboriginal people I know or meet, my relationships with them and attempts at relating, from a position of respect and appreciation; describing highlights and difficulties, without passing judgment." |

[Above] Ring Tailed Dragon, Watarrka National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

Mooney has worked for landcare projects with Aboriginal people in Central Australia. Her two connected poems, The Coming of Nungarrayi and Miracle in sand country explore her relationships with the land, Centre country women and the incongruous reality of landcare projects in an Indigenous context.

The coming of Nungarrayi

Nungarrayi must have gone to the funeral

She had flowers.

(Nungarrayi clasping orange plastic lilies,

an elderly madonna.)

The photocopying teacher

stabs at buttons.

Her friend sits with a book

fat with yawns.

I make tea

with bore water matured in an urn.

Powdered milk aged to flour.

Throw it out.

At the pension camp, people are sitting

on warm raked ground,

strolling among shadows

long with the promise of evening.

A cool wind

skips around.

Nungarrayi is coming.

You wait.

I sit down

You used to live here, eh?

Yuwa, I work for landcare now, collect seed.

A young woman picks up something

discarded since the last raking,

pulls it in half.

Pale green flesh,

firm like an unripe apricot;

scrapes shiny black seeds

into a lid.

Bush tomato.

Presents me with a brimming lid.

We talk about the coming of Nungarrayi:

she's on foot,

she should be here soon,

maybe she stopped,

maybe at this house, maybe that one,

she doesn't appear.

It's getting late for me to make camp.

You wait.

Finally,

See, there she is.

Look! Over there!

Nungarrayi,

this woman with whom I share

only a smattering of words.

She gives me a bear hug,

accepts bush banana seedlings

with slight confusion -

there's plenty in the bush.

Yes, yes she'll come seed-collecting tomorrow.

How many ladies?

Three. She sings them on her fingers:

Meee, Pil-yar-eee, Dais-ee Nakamarraaa.

Miracle in Sand Country

Somehow a mad Daisy

also comes

on our quest

into the sand country.

Look punkuna!

You can eat this now,

peeling big green seeds

out of pods.

No, not bushtucker,

I want ripe seeds

for growing plants.

You don't want bushtucker?

Look, this one, bush banana,

good food.

What about watiyawanu?

Suddenly the country is full of seeds,

neat bunches, corkscrews of pods,

others hang single and straight

like petrified rain.

That watiyawanu is still green, isn't it?

We take it back,

wait a few weeks, it be right.

They head off

barefeet around spinifex,

keeping their distance

from the mad Daisy.

Further along the narrow rattly tracks,

we pick minytju, ripe crackly pods.

Can you clean them for me

- get the seeds out of the pods?

A racket of threshers and jumble

of sieves in whitefella technology.

One of the Daisies

plonks herself down

on the side of the track,

tips her bucket of seeds

into her ample lap,

crunches up the pods,

begins chanting,

raising and dropping

her arms,

raising

handfuls of seed and chaff,

seed dropping into her lap,

chaff taken by the wind.

The other women

look at this Daisy,

drop to the ground,

pour their pods

into their ample or skinny laps

chant,

raising and dropping their arms,

raising and dropping.

To my Sydney friend

it's the Catholic Womens' Guild,

singing hymns as they knit.

The miracle of pure brown seed

pours into my bucket.

The use if indigenous language and terms sits comfortably within the poems like the kind of hesitant pidgin/patois that white people adopt as they learn scraps of language, both sides struggling to make sense of each other with key words, teaching words, untranslatable words and phrases, trying to feel the way towards meaning. Misunderstanding and the inability to communicate in 'normal' ways is a constant reality of life for a non-Indigenous person in a remote community, as much as it is a profound difficulty for traditional people at this interface. The poem, Collecting firewood, speaks about relationships forged through simple actions in an environment of dwindling resources and land degradation.

Collecting firewood

As the setting sun

streams through woodland

we wrench chunks of mulga

off dead trees

into the back of a truck.

I want to drive on

in the golden light

sprawl on the ground

beside a campfire

talk in the soft sweet evening.

But we go back to the community,

to a corrugated iron cubby

where an old woman

sits on a chair,

directs mulga

on to her fire

beside her fire

beside her neighbour's fire.

My doctor friend folds rugs

for a back-rest

for an old man

who can't walk,

sits on the ground in a corner.

I ferry

a wealth

of firewood

throw out scraps of words

that kindle

long runs of replies,

rhythms as familiar as red sand,

that I can't understand.

[Above Left] Long Bum, Charles Darwin National Park, Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001) [Above Right] Apostle Birds #5, Katherine Gorge, Nitmiluk National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

David Kirkby left the Northern Territory reluctantly and has since experienced deeply the reverse culture shock that is a reality of reentering 'mainstream' culture. He was based in Central Australia and since leaving has spoken often of a sense of longing for a country that he was intimately involved with ... "I still miss Alice, and the whole NT, very badly indeed." Kirkby agrees that it is hard to write about the landscape without talking about the people. "It's hard to write about the NT without that underpinning [of the land] ... it's what the poetry stands on, just as the people do. "Kumanjayi" is typical of this, starting with images of the land and then moving on to the people and their lives."

Kumanjayi (no name)

The sun lifts lightly from the land

like a bright sheet peeled from a bed.

It is warm still - the heat from the red

dust like liquid poured out upon the sand

as I wait in a crowd of sticky children,

camp dogs and quiet men clustered outside

the clinic in a shroud of noise from the women,

beating their heads with rocks and wailing into the wide

open reaches of an all too common grief.

They will not call the aeroplane tonight.

No kerosene flares on the airstrip signalling relief.

Just a few hours of darkness before the desert light

returns, dragging with it tomorrow and a dead

child, and a name which can't be said.

The intense personal sense of belonging that Kirkby experiences with the Central Australian landscape is evident in "Kaltukatjura", but it is a belonging paradoxically caught in the dilemma of the remote area worker who is acutely aware of being a foreigner and not belonging.

Kaltukatjara

The name forms on my tongue.

The houses sprawl in the sun

like camp dogs,

curled up at the foot of the hills.

Beneath them

the land lies still,

untouched by their presence.

Are the souls of the people so?

Stranger here,

I cannot know.

I came just yesterday,

following your stories and

the wandering of my heart

down the long track

south from Kintore.

The track wandered too,

a fine brown thread

amongst the dunes,

tangled, yet

weaving a pattern still,

sewing sand hill and spinifex

ever more tightly

into the tattered fabric

of my life.

I looked hard but

found no message in the sand

and, at last,

both driver and driven,

I arrived at this place.

Now the face of the hill

is turned towards me.

The sun slips away

at my back and,

after all of this,

all that I can see

is your absence.

And I realise that

the hills of Kaltukatjara

became a part of me

long before I saw them,

and though those hills

surround me now

they are not what I see,

for what I see now

is what I saw from the start -

the wind carved mountains

of my heart.

Kaltukatjara.

Serpentine Gorge, West MacDonnell National Park, Northern Territory, Australia (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

In "Spinifex (leaving Alice)" the pain of leaving the Territory is manifest, deeply engaged with the physical environment and expressed as a physical incursion into the poet's body.

Spinifex (leaving Alice)

Leaving

was something

I let myself do.

Let the car take me south

through Heavitree Gap.

Let the plane lift me up.

Let the mountains fall down

like the hands in my lap.

Let the land become

a picture of itself.

let the wide desert sands diminish

to a size I could compass -

a dot painting, a map.

Let my life become something

less than it was -

a memory, a story,

a scrap of home made paper

furred at the edge

where you tore the page across.

I'll never know

what was on the other half,

what was lost -

like my life,

torn on the line

of one plane journey,

one straight knife slash

across a continent,

which should have been

quick and clean

but which left

such ragged edges,

such permanent reminders

of what I left behind.

Like the spinifex spines

in my leg

broken black tips of

long green needles

from the shattered rocks

of Mt.Leibig, Mt.Zeil.

I didn't feel them

at the time,

the desert being too real

to admit of such small pain.

Weeks later though

they worked their way out

like tears squeezed

from a dry land.

memory is like this -

the broken barbs of things

lodged deep within,

working their way out years later,

reminding you of the too bright air

and the blue blue sky

on the day they needled in.

The history of landscape, tracing back through recent and distant pasts, the significance in the act of naming, is the subject matter of the following poem where Kirkby says "... I'm trying to indicate at least something of the layers of meaning human habitation place upon the landscape. The names are important...at least two Aboriginal names and one new European one." The poet acknowledges 'at least' these names, knowing there are probably more.

Examine the name of any place in the Territory and these layers emerge; European names, formal and familiar; common use Aboriginal names; sacred Aboriginal names that will sometimes be revealed; names given by different clans to the same place; names changed and refashioned because of the uncertainty of spelling and pronunciation; the place itself not constant either as the landscape changes and refashions under the force of climate and the conscious development of towns and settlements and new cities.

Watiyawanu ...

Amundurrngu ...

Mt Liebig ...

The names fall away

into emptiness,

like the spinifex

lapping at the peak.

Dry creek beds

drain the slope,

already dry beyond

all hope of rain.

Only the winds remain,

blowing gently

into the quiet land,

stirring the desert sands which,

grain by patient grain,

are weathered from the hills,

settling on the plain

in shafts of silent sunlight,

gently, secretly,

beyond the echo

of the names -

Mt Liebig ...

Amundurrngu ...

Watiyawanu ...

[Above Left] Pied Butcher Bird, Yulara, Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000) [Above Right] Uluru #17, Uluru - Kata Tjuta National Park, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2000)

I have not attempted to discuss in this article the work of Indigenous poets in the Northern Territory and their relationship to landscape but there is one poem I would like to end with. It is a poem that the poet, Rosemary Plummer, told me once came to her "all in one piece, all at once ... that's why I wrote it in a circle". Plummer is a Wurumungu woman from Tennant Creek, a woman serious about her poetry and the importance of teaching people about her culture through her writing. In this poem, one can almost hear in the background the soft chanting of the ladies in Mooney's poem, the chanting of women who understand the rhythms of the country and how to be in it, how to be completely a part of its cycles without resistance or striving for belonging, for what has not yet become manifest. The poem embodies all those elements of intimacy, connection and relationship that are so much a part of the poetry of the Northern Territory.

Silently

Not a wind

nor air we wait silently for

our spirit to tell our body had been

healed we wait patiently for the circulation

of the weather and the right time to gather bush

potatoes no sound of the snake hissing in the grass we

wait for rain wait and wait a bush fire burns the

ashes fall the fire leaves no track the root of a tree does

not exist any more a new tree must grow a new life start

how long now it gotta heal up I hear a voice must be must

be far away we paint our bodies no preparing to dance a

whirly wind swirl and swirl leaving broken branches and

leaves it makes the heart pound like a clock long time

now long time but we'll wait and wait just like a mother

giving birth to a new born baby I see the stars above at

night wonderful a silent river flows makes our spirit

inside of us calm so we'll wait silently patiently

for our spirit to tell us our body had been

healed and for the right time for the

circulation of the weather no

preparation to dance but

to wait wait wait

The poems in this article by Kaye Aldenhoven, Prithvindra Chakravarti, Meg Mooney and Rosemary Plummer were reproduced with the permission of the authors from the publication Landmark: Poetry From the Northern Territory. Kaye Aldenhoven's poem "The moon is full and evil spirits can see their shadows [Dird nayuihmi narmande gabarriwoyiknarren]" courtesy of the author. David Kirkby's poems provided courtesy of the author.

About the Writer Marian Devitt

|

Marian Devitt was the Executive Officer of the NT Writers' Centre from 1996 - 2000. She is the editor of Landmark: Poetry from the Northern Territory and has written articles about the Territory for Overland, and Art Monthly. She also writes poetry, prose and plays. Marian is currently working on a one act play called 'An Octave Above Sound' for production in Darwin in 2001 with four other Darwin playwrights. |

[Above] Photo of Marian Devitt by Scott Webb, 2000.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.5 (March, 2002) |