MULLUM DREAMING: LIFE OF A YOUNG POET

By Edwin Wilson

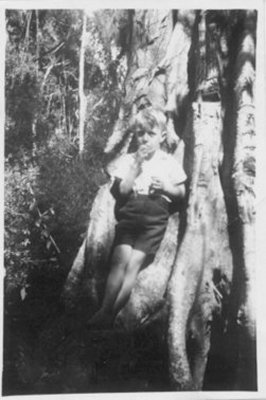

[Above] Chincogan, Mullumbimby, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Edwin Wilson, 1983)

I lived in Mullumbimby from 1948 - 1958, in the shadow of its guardian mountain, Chinny or Chincogan, from the ages of 6 - 16 years. From an eclectic mix of soldier, sailor, Admiral, poet, felon, farmer I'd inherited a 'romantic temperament' but not the spelling gene, and grew up against the odds to be a poet.

Chinny was a dominant feature of my horizon, and I worshipped that little mountain in an active, pagan way. It subsequently became a Muse, just as memories of Ben Bulben, the beautiful mountain of the childhood of W.B. Yeats in Sligo, had stayed with him all his life. Indeed my first book of poems, Banyan (1982), was dedicated 'for Chinny (or Chincogan)'. At the time I was unaware that Henry Kendall had dedicated his third (and last) book of poems, Songs of the Mountains (1880) 'To a Mountain' (North Brother Mountain, near Camden Haven/Kendall).

Prior to that I had lived in an isolated farm house without books, electricity or running water, in a sea of weeds at East Wardell. My father Tidge was a tractor driver/sugar cane farmer who died before I was born, which introduced me to the forces of chaos and made me aware of my mortality at quite an early age. Some of my earliest memories are of the flannel flowers at the Wardell cemetery, and how the sand was burning my bare feet. This absence in my life was keenly felt, and left a psychic void that surfaced many times in many ways, but mostly as an aching emptiness. In retrospect it was a hurt that never went away, and left me grieving for a person I had never known. So I became a hoarder, a collector of stray memories and yarns to try to keep the memories alive. My father left no letters or Journals, which may have heightened my urge to leave some form of written record as "my letters to the great unborn".

[Above] Farm house at East Wardell, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Edwin Wilson, 1983)

The absence of books in my early life was counterbalanced by a strong oral tradition, which helped fertilise a purple pictorial imagination. An ancestor was supposed to have been the English cleric, outsider and pastoral poet, George Crabbe, so the scribbling itch may well have been in my genes. The other great advantage of coming from peasant stock was that I'd never been intimidated by the weight of literature. Had I been aware of how hard it was to write and what had been written I probably never would have started in the first place.

Part of the oral tradition was about another writer ancestor, a dark, severe, and somewhat distant soul who looked down from the wall at my great aunty Nina's place at Grafton. Nina's great uncle had written under the name of Oliver Bainbridge, "his nom de plume, pen name, you know", she used to say. After a stint in Grafton gaol young Oliver had been thrown out of home by his father for disgracing the family name. "I will change my name to Oliver Bainbridge," he said, "And travel the world and become famous, and you will get no credit as my father". That night when it dawned on him that he was really out in the cold he heard the frogs calling 'Dark Ork, Dark Ork'. "I know it's a dark walk you bastards," he said, and it's an expression of the strength of his personality that this story has been retained in the family folklore for more than a hundred years. Bainbridge become a writer, 'explorer', 'anthropologist', orator, and spy for Empire, but came to a sticky end. He'd lived by his wits and was finally despatched to his eternal by the IRA with an 0.45, aged only 45.

* * *

After Wardell we lived at Brunswick Heads, where I started school with slates. Little wonder I still marvel at computer technology, that I can carry a developing book around in a little metal and plastic thing in my top pocket. My early schooling was disrupted, so consequently I never properly learnt to spell or add up in my head.

|

Everything was somehow grander, and larger than life in Brunswick in the 40s, in the shadow of the 'Big Scrub', the largest sub-tropical stand of tall forest in New South Wales. Giant archaic beetles came out of the Gondwanan night and ground and crunched under the street lights. Toe-biters they were called, some 2-3 inches long, with nippers at the ends of their front legs. The night belonged to the flying foxes too, who traced their erratic flight from star to star, with flapping sails, and raided the fruit trees. Some of them were caught in the telegraph wires and hung on those gibbets until they were consumed by maggots and rotted away to nothingness, except for scraps of skin and claw, which made me wonder what was left of Tidge by now.

Harry Devine's Hill, on the northside of the mouth of the Brunswick river, could only be reached by boat. It was a place for lovers and fisherman, with walking trails into the jungle brush, and elkhorns, palms, and bird's nest ferns, and monkey vines a child could climb and swing upon. I loved to sit in the sand and sift through the grit, beside the pitted skeletons of many ships that had been wrecked on that treacherous bar. |

[Above] Peter (Edwin) Wilson going to school at Brunswick Heads, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Jean Forbes, 1948)

There were so many things to see beside that graveyard by the sea, all white and clean, with the exception of dead fish or rotting cunjevoi. There were the bones of molluscs, called shells, and pieces of shells with their spiral staircases, and coloured stones with smooth round inlays, and pieces of sea urchin with their pincer teeth. This is probably the most serenely happy I have ever been at any time in my entire life.

Happy was the sand boy indeed, playing with his boats and shells on the sandflat at Brunswick Heads near the deep green channel as the tide came in. The lapping froth came up the channels first, where poddy mullet swam, and filled the little valleys of the rippled bar, dissolving the sand pellets of the soldier crabs.

Mullumbimby was a 'cowboy' town in the 1940s and 50s, with an operating smithy, and places to tie up the horses in the main street. I had a Tom Sawyer childhood. I went crabbing, fishing and swimming in the river, and played in the remnants of the 'Big Scrub'. We later went for holidays and picnics at Broken Head and Wooli, which gave me a deep love of the wallum heathlands and coastal rainforests. I was moved by the exquisite beauty of the area, the poetry of place. Indeed the initial inspiration for Banyan came from the rainforests around Mullumbimby. My aesthetic sensibilities were yet to rage and range, and yet my heartland was its genesis. Mullum was indeed a paradise of sorts. The vegetation was luxuriant, the wildlife was everywhere, so it was only natural that I became a naturalist. I caught mud crabs and cooked them in a pot and sold them for 3/- each (a lot of money then) in the local pub at closing time. The first thing I ever bought in a shop with my crab money (apart from lollies) in the pioneer tradition was a little axe.

It is interesting here to note that D.H. Lawrence used the name Mullumbimby for the town in his novel Kangaroo, which in truth was Thirroul, on the coast just south of Sydney. He must have looked at a map and picked the town for its sound or euphony. It certainly wasn't the Mullumbimby I knew. The town that he described was squeezed between the sandstone cliff face and the sea, and the plants that he described were so different to the plants I knew.

I initially collected rosellas plucked untimely from hollow logs and snared in the back yard. A boy in class kept blueys (rainbow lorikeets) and greenies in a cage behind his house. I was in the vicinity one day when his lorikeets were calling to their brethren circling overhead. I hid in his back garden as a rainbow came down from the sky, to tumble in the mulberry tree, and bend its branches to the ground. The wild birds landed on the cage itself, kissing its inmates with their beaks, before such a thing became a daily ritual at Burleigh Heads, and it was so beautiful it almost hurt. Enraptured, I stood up for a better view. There was a warning call, just one high screech, and they were off like a squadron of Canberra jets.

Soon after I caught a female rosella and her mate dashed himself repeatedly on the cage. In the morning he was dead and lying crimson on the ground. In an act of piety I took my little tomahawk and smashed my cage and let all my parrots go. My first wife later told me about W.B. Yeats (I'm sure that's who it was) and how he'd found a dead bird on the beach and had been so moved he knew he was a poet. I tried to tell her this particular story, but she did not want to know. After the parrot incident I transferred my collecting instinct to the epiphytic ferns and orchids that grew in the surrounding forests.

* * *

|

On the cusp of puberty I ripped them joyfully from rocks and trees and took them home as trophies in my belt, unknowing that the word 'orchid' came from the Greek for 'testicle'.

My Mullumbimby childhood was a time of sweet intensity and I found solace pottering in my orchid house. But to quote from Robert Louis Stevenson the 'heart that is first moved by the flowers is the first to be pricked by the thorns', or words to that effect. I had my angels, but I had my demons too in paradise. The dreaded razor strop that hung on a nail in the bathroom wall was one of them. The others were to do with bullying at school, and coming to terms with death and sex, and rituals to appease my mother and the mountain, and my breaking away from God. My mind had been confused with religious instruction at primary school. Rituals were devised to stop the mountain from exploding and burying us alive and screaming for our sins under a red-hot cloud of ash. For children are much closer to the heart of things. I knew the ring of fire we were living in. For the mountain had been there since the lava cooled, a jealous protector of our little town, and had to be eternally appeased. |

[Above] Peter (Edwin) Wilson in rainforest, Mullumbimby, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Jean Forbes, 1950)

I'd been a lonely child back on the farm, relating mostly to adults. I'd launched crude ships on the Richmond River with messages written on their paper sails, in search of a soul-mate but received no replies. Years after, on a carriage wall in the London tubes, I saw the poem 'Where Go the Boats' (also by RLS), that expressed this sentiment exactly, and I quite literally launched my first three books in sailing boats in Sydney Harbour. Only one ever came back. At school we were writing letters to Santa. A letter had also been written to an aunt in Lancashire on the weighty matter as to whether ladies in England passed wind, and a reply had been received in the affirmative. I therefore decided to write a letter to my father with God in heaven. An aunty had once sent my father a postcard from Townsville. I felt cheated not to have received a similar communication from my father of any kind. It rankled to think that Tidge was enjoying himself up there in Heaven without so much as a postcard with a dashed-off passing thought, 'Having a wonderful time/ wish you were here'.

They were all rather vague when it came to an address. The usual response was a wave of the hand, as if it were somewhere beyond the moon. My grandmother said I was a very wicked boy and should pray for forgiveness. It seemed rather strange that I should have to pray to God to ask him to forgive me just for asking where he lived.

When I started the letter I didn't quite know how to begin. Mr God didn't have the right ring about it, as I didn't even know his Christian name. Dear Sir didn't sound much better. Finally I just wrote Dear God, and addressed it C/- Heaven, oblivious of the Dead Letter Office, assuming the people in the Post Office would surely know.

I never received a reply and thought this was rather rude. But God was probably too busy worrying about sparrows and the like. God probably even had a silent listing and address to stop crank prayers, begging letters, and other nuisance or junk mail. How could I believe in such a God who'd dealt me such a crook hand? On the other hand it could have been much worse, as I'd not been born in war-ravaged Europe or in some slum in Africa or Bangladesh.

In upper primary I was a precocious child, and hovered in a nether-world between a brat and fool, and got into trouble all the time. My mother was sick and depressed for a couple of years so I ran wild and free and slightly feral. I'd always been clumsy, an accident just waiting for a time and place in which to happen, and it's a wonder I survived to tell my tale.

|

My dreaming led me into telegraph poles that popped up mysteriously in my path, and I once walked into a dog in the main street in Lismore. If anything my greatest sin was that of curiosity, which killed the cat.

I'd always been a talkative, imaginative, and rather highly-strung child, and interested in almost everything. Later at Teachers' College I tried to toughen myself up, to compensate for 'artiness'. Growing orchids was surely bad enough!

For the primary role of country life had been to turn boys into men, and that meant brutal. So I went out and bought a gun, the natural country thing to do, and shot and skinned rabbits and kangaroos, and almost anything that moved.

I used guns and blood to help quell the feminine in me, to help make me cruel enough to rank in male society, in preparation for the adult world of love and work and territory. |

[Above] Peter (Edwin) Wilson at Wooli, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Jean Forbes, 1949)

But even blood could not deny the other side of me. Creative flashes continued to pop like the proverbial flash bulbs in my head. As a child I converted an old chook pen in our back yard into an obstacle course and 'ghost house'. The local kids were charged six pence (or six marbles) for the repeated thrill of being 'scared' and having water poured over them in the dark. My step father once told me he would give me five pounds (an incredible amount of money then) if I could catch a fart in a bottle. The inspiration came to me in the bath as I remembered rising bubbles. It was a real 'Eureka' moment. I quite literally caught a fart in a clear vegemite jar by the 'displacement of water method' for gaseous collection. The bastard welched on the deal however, and never paid.

I was probably more a painter than a poet as a child. A grandmother had flattered me into believing I had some talent in this department. I had to repeat sixth class as I was too young and too immature to go to high school. The teacher let me paint most of the time in class, so naturally I thought I'd be an artist when I grew up. Mostly I painted my little mountain, Chinny or Chincogan, as Cezanne had painted his beloved Mont Sainte-Victoire.

[Above] Peter (Edwin) Wilson at East Brunswick, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Jean Forbes, 1948)

Throughout all this I kept on talking and laughing, and my poetry was relegated to snippets of smutty verse. I found I could make kids laugh, and learnt to deflect the barbs by playing the billy goat. Sometimes as a result of glee or flashiness, mere words would couple in my head, akin to copulation. And sometimes, just sometimes there was magic in the air as words conjoined, as if they always should have been that way. My friends would say, "you're a poet/and you don't know it", to which I'd reply "When I grow up to be a man/I'll be a poet if I can". Not that I can claim this as an early manifesto. My mantra hadn't come from any deep and abiding search for truth in art, but because it was a saying, and because it rhymed.

My first poem, My bike, was written in year 5, when I was 10 years old. I can clearly remember its genesis in this my 60th year. My friends all had good bicycles and they were a primary status symbol to a child. But we were dirt poor. I had a terrible old bomb bike that had been cobbled together from spare parts salvaged from the town dump. It was always breaking down. One day I was riding to Brunswick Heads and came to a corner on the flat ground just before King's Creek. The handlebar wobbled and turned right around and then fell off. Burning with shame and humiliation I wheeled the bike back home, kicking the wheel from time to time to help it turn around, and felt so frustrated that I was moved to verse. My early jottings were dispersed when we moved house one time. I subsequently dredged this poem up from memory intact, aged twenty three, when I had been moved by love to verse again.

Although we were not expected to write poetry at our school we were certainly exposed to the Australian tradition of bush verse. If we were good Bill Bouveret read us Henry Lawson and 'Banjo' Paterson, and their world was just outside our window, and Mullumbimby could have been Barcoo, or Ironbark. I adored 'The Man from Ironbark' and 'Mulga Bill's Bicycle' and 'Bush Christening' and could recite them all by heart. They just seemed to go 'click' in my head after a couple of readings, like a mnemonic linked in with rhyme. That skill alas, like others, has diminished over the years.

[Above] Chincogan with Mullumbimby peaks, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Edwin Wilson, 1974)

My mother always denied my avocation, even when I was included in the 1996 Oxford University Press edition of Australian Poets and Their Works. It may have been a working-class thing, a desire to kill unrealistic expectations. Inspired by Oliver Bainbridge she'd harboured thoughts of being a writer herself, and had had a story published in the Women's Weekly or equivalent when young. She therefore may have had another axe to grind. Statistically I was less likely to die from a bee sting than being eaten by a crocodile or shark, than being struck by lightening, than having a book of poems published, than being kicked to death by a mule. Putting it the other way round I was more likely to be kicked to death by a mule than become a published poet, at least before the electronic age. No wonder my mother was trying to put me off.

On the other hand not having the mad assurity of a destructive talent I knew I couldn't live by verse alone. For Bainbridge, after all the self-promotion and the pomp and circumstance and ceremony of his life had died in penury, and had been given a pauper's funeral. And coming from the rural working classes meant I couldn't afford to fail as there was no fallback option. So I knew instinctively that if I were to escape from rural poverty I'd have to work, and subsequently have held down regular jobs throughout my life.

* * *

There was a country myth that Chinny had been surveyed during the war and was only nine hundred and ninety nine feet high and needed to be a thousand feet to be a proper mountain. In 1953, after the ascent of Mount Everest, my friends and I climbed Chincogan to erect a cairn of stones to give it mountain status. That day on the mountain top I saw beyond the constraints of my beautiful little town, and knew I'd have to leave it all to work and grow, but thought I'd do it on my terms. One of my first adult poems, 'Homage to a Mountain', dedicated to Chincogan, was written in 'brown exile' at Armidale.

I spent time at Tidge's School (at Wardell) at the end of sixth class, and stood up at the Christmas Party to recite some of my poems. I can remember my grandmother sitting in the audience and looking both exceedingly proud and slightly embarrassed at the same time, if that is possible.

Just before I went to high school my mother said she had something important to tell me. She had christened me Edwin James Wilson in memory of my father but had then proceeded to call me Peter and Peter had stuck. When she married Henry Forbes, cabinet maker of Mullumbimby, some people called me Peter Forbes, and I had to struggle to stay a Wilson in my mind. Now after some eleven years on earth she told me my name was Edwin and not Peter and I found this very difficult to cope with.

|

I didn't have the strength to fight my mother at that age, so changed my name. To make matters even worse I later discovered that Wilson wasn't even the family name. My great grandfather had been an illegal immigrant who came out in a whaler from Denmark. He'd jumped ship in Sydney during the Gold Rushes and anglicised his name (like Henry Lawson's father had done). I now believe his father's name was Jens Jensen Sondelev.

Given my identity problems as a child I once (and only once) established an alternative persona, of 'Eileen' Wilson in 1975. One of Eileen's poems was published in Kate Jenning's Anthology of female verse, Mother I'm Rooted, (a very mild Ern Malley thing) and I got a lot of stick for this back then.

During the Christmas holidays we used to visit great aunty Nina at Grafton. Her husband, also called Henry, referred to me as 'Peter Felix', for despite my squalls I was essentially a buoyant, happy-go-lucky sort of kid with just a peck of murder in my heart. That didn't mean I didn't get frustrated or melancholy, for poets, almost by definition, must be reflective souls. But like a weighted rubber doll I just kept bouncing back after each hook and jab from life. |

[Above] Peter (Edwin) Wilson with fluffy dog, Brunswick Heads, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Jean Forbes, 1948)

Meanwhile I started high school with a new name, a barefoot, 'different' child and I was taunted for this 'difference'. Then I became a mad keen 'boy scientist'. The bangs and smells of science attracted me, and promised to answer the bigger philosophical questions. At this time I challenged my religious instruction and was expelled from class for wishing to talk about evolution, and set up a rival faction down by the creek.

No doubt I was a super nerd, but subsequently played in the 8-7 football team (Rugby League), and most of the taunting stopped. My English teacher at school, Wal Wardman, introduced me to Slessor and Keats, and once read us the 'Pipes of Pan' by RLS. That's when I fell in love with Deidre McLean, a dark-haired Celtic beauty in our class, when even Shakespeare became intelligible.

Just when things were looking up the cabinet-making business went in to serious decline and Henry Forbes was forced to move to Tweed Heads chasing work. That forced departure from Mullumbimby was very painful. It was as if we'd been expelled from the Garden of Eden, and my heart has ached for those green hills for half a life.

|

Since those days I've certainly had my moments, my periods of anguish, self-doubt, depression, and writers block. To keep my focus and my productivity I've had to be quite ruthless with my time. So consequently I've not had the time or energy to play the 'networking' and 'political' games too well. I've been too occupied with the sordid business of earning a crust, and then trying to write books, raise a family, pay the bills and all of that. In the long run I assumed it was more important to produce a body of work than to swan around at conferences. |

[Above] Chincogan from Argyle Street, Mullumbimby, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Edwin Wilson, 1974)

I must have had the necessary type of personality, as I've kept at it and have now been working at the craft for more than thirty years. In later life I obtained a job at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney, the closest thing to a rainforest in the city, which, considering the orchid passion of my youth, was wonderful. Indeed this has been a gift of a job for me, and linked me back in part to the child I may have been, for part of me is still that child.

In 2000 I published The Mullumbimby Kid, a story of poetic genesis. Mullumbimby has always been a well to me throughout rough patches in my middle life, an exilir or balm from which to drink a lifetime through. My heart would always skip a beat whenever I saw Mullumbimby on the TV news, mostly for excessive rainfall. I have been Mullum Dreaming all my days.

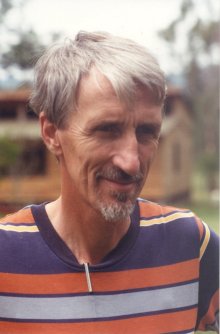

About the Writer Edwin Wilson

|

Edwin Wilson is a poet who has published fifteen books to date (2002). He was born at Lismore, New South Wales, in 1942 and originally lived at East Wardell, then spent a formative decade, aged 6 – 16 years, at Mullumbimby. He completed a science degree at the University of New South Wales in 1967. After working as a science teacher he lectured at Armidale Teachers’ College (1968 – 1972) and planted a garden of now maturing trees at 'The Poet's House'. In 1972 Edwin Wilson was appointed as an Education Officer at The Australian Museum. Since 1980 he has worked in community Relations at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney. He is listed in the OUP publication Australian Poets & Their Works (1996), the second edition of The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature (1994), and both editions of W.D. Thorpe’s Who’s Who of Australian Writers. |

[Above] Photo of Edwin Wilson by Paul Pulati, 1990.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.5 (March, 2002) |