As a performance poet, it was exciting to be in a country where the whole crowd can dance at the soccer. Most of the great poets in the national literary canon are still alive and oral culture is stronger than written culture. In Indonesia, I have read poems to enthusiastic audiences of tens of thousands of devoted listeners. That is almost inconceivable in the Australian performance poetry scene. Those devoted listeners held me there for five full-time years.

I first met an Indonesian poet at Jakarta's Ismail Marzuki Garden in 1993. He was Jose Rizal Manua, a performance poet and theatre director based in Jakarta. He has one of the most beautiful voices in Indonesia. He wrote the following poem to comment on the catastrophic deforestation he witnessed when he lived in Kalimantan (Borneo) for 8 years. This poem is a good example of the way Islam and poetry are positive moral forces in Indonesia.

Allah Ya Rabb (Invocation of The Carer)

The ozone layer groans

echo round the globe.

A swelling cloud of dark deceit

crashes on our universe

with damning smoke.

Monolithic trees trunked

sail to the ocean

on barges of suspicion.

& all through Jakarta

the busnessmen's laughter

is climbing in towers of glass

& no neighborhood burning

can stifle the yearning

that suffers with each new law passed

& the wild swelling moon

can't damn up the tune

as her worshippers scream through their masks

|

Wholly Globe!

The angels pawn their wings

to rivers of spew's dregs

& bulldozing greed

laughs & farts into the sea

Wholly Globe,

where can we go?

Flood & drought

& volcano.

where can we go?

& Jakarta's announcing

the businessmen pouncing

to make all the jungle go bald |

[Above] Kiai Hassan Bisri )Praying near Mt Semeru. (Photo by Geoff Fox, 2002)

& the whole city burning

can't stifle the yearning

to run to the globalised world

& the wild swelling moon

explodes with the tune

of her worshippers slowly being mauled

Wholly Globe!

Wholly Globe!

& policy's hills

are stuffed to the gills

of ships that tack to a nod

& bullets of fraud

are scattered in hordes

that spit in the gut of the fog.

Where can we go?

[Above] War and Peace at Mt Semeru. (Photo by Geoff Fox, 2002)

In 1994, I spent 6 months in Indonesia involved in research on women poets. Women did not feature prominently in anthologies and readings during the repressive Soeharto era. My instincts told me that there would be plenty of great women's poetry going unheard somewhere. That year I met the sophisticated linguist Omi Intan Naomi. She embraces modernity in a thoroughly Javanese fashion, as in the following poem:

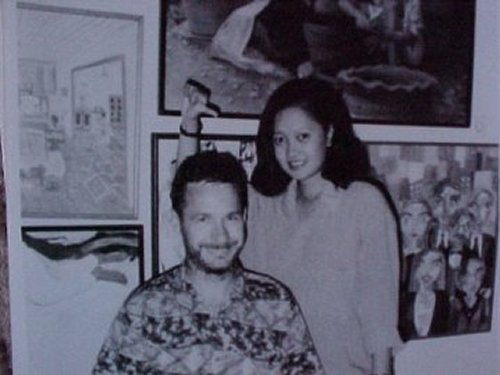

[Above] Omi Intan Naomi and Geoff Fox. (photographer unknown, 1994)

CONUNDRA WITH THE CORN FLAKES

taking a good long hard look

at my coffee cup

it's as if we just met;

a wild idea

welcomes in the day:

Is the pot's emptiness

or contents

meaningful to me?

Is possessing you

or letting go

getting it on?

Are loving

& hating guts

very far apart?

Is life or death the end?

Taking a good look

at my emotional apartment:

Is anybody there?

That year I also met Sipon's husband, Wiji, a master of plain speaking Indonesian; his father, a becak (rickshaw) driver, had been unable to finance Wiji's education beyond primary school; but Wiji's natural talent and determination led him to become an internationally recognized poet He was a fearless proponent of free speech during the repressive Soeharto era. The following is an example of Wiji's uncompromising honesty in portraying factory workers' lives:

|

LEUWIGAJAH

Leuwigajah goes

morning on to morning,

bus of the cheap force,

rumbles down the bitumen

in front of its own dust.

On machinery goes

working on the workers

sweating without bathrooms

no lights, no taps, no windows

laid out on the sleeping mats

on floors as cold as tombs. |

[Above] Tethered Horse. East Java. (Photo by Geoff Fox, 2002)

The old tongues tell the tale

like a chronic bloodied cough,

lives of overtime coerced

no extra pay just blank heart stares

bodies flake fingers break

& strikers are struck off like unwanted hairs.

The bodies of the children

flow into Leuwigajah;

they're fruit sucked of vitamin;

the machinery still crushes

up the 24 hour force

in & out the button's pressed

& trucks full of the products

slide to sell, sell, sell

Leuwigajah goes

morning on to morning,

the sludging chimney smokes;

sometimes the river's green

& sometimes it runs red

but on & on machinery goes

working workers dead.

[Above] Untitled. (Artwork by Geoff Fox, 1994)

In 1996, I was planning to spend two months in Indonesia, but ended up staying for four years to write in response to asmaulhusna (a scheme of 99 names for the object of worship). My interest in asmaulhusna began in a bookshop in Yogyakarta: I suddenly became transfixed by the title of one book: "Sembilan puluh sembilan untuk Tuhanku" by the Sufi pop star poet Emha Ainun Najib. The title means "99 for my God". I spent a lot of time at Emha's small madrassah cum orphanage over the next year and also met three exceptional women poets, Abidah, Yuyum and Irna.

When I first met Abidah El Khaliquy, there was a controversy raging in the Indonesian media about voluntary termination of pregnancies. I told Abidah that Australians might be interested in hearing an Indonesian perspective on this issue. About half a year later, Abidah presented me with a set of seven poems, an extraordinary outpouring of words and images which had started as a response to the question of abortion but turned into a powerful portrait of the status of women in a patriarchal society. This is the third poem of that series:

|

BLADE (Woman Song 3)

In the end the backyard doctor asks,

"Tell me who the bastard's."

but there's a realm of trapped voice

where she's free to make noise

about the old man & her brothers

raping gaping at her

when & where they want

& the others

as they want

as they want:

She is in their realm |

[Above] Abidah and Daughter. (Photo by Geoff Fox, 2001)

of tight trapped voice

& all the blades thrust at her part

& all the scalpels stuck into her gut

so blood flow pool clots down crotch

shrieking out the flute revenge

the drum of revolution

sounds & sounds again

She is in their realm

of tight trapped voice

raping gaping at her

when & where they want

& the others

as they want

as they want

[Above] Sidorenggo Kids. (Photo by Geoff Fox, 2002)

Yuyum Atmadja is a softer poet who writes with extraordinary empathy for the poor people of Jakarta. She was working as a school teacher holding down 3 jobs with 60 contact hours per week when she wrote the following poem. It is written through the eyes of a school child whose mother was the victim of the infectious diseases which hit poor people in times of economic downturn:

BUNGA RUMPUT (weed flower)

Looking at the window frame

I see a wild flower loom

& I shield my eyes to cover

up its blooming bright flame

that sees me like my mother.

I've stopped work as if I'm held

by her warm embracing eyes

back here from that other world

so calm, so strong, so wise.

The city river has turned gray

Dad says he used to fish there

My mum grew thin & went away

I just want to see her.

The bright flower outside class

dances between my fingers.

She blows me kisses through the glass.

The friend I need. She lingers.

Irna Hidayati's poetry brings magical sensuality to her religious passion:

REMBULAN (moon)

Moon, I want to take you in

to hug up all your light

& and file you as my heart

|

the soft warm I sleep in.

Moon, I want to eat you up

to kiss off all your light

& bury it inside me.

The longer English literary tradition stretching back through Wordsworth, Shakespeare et al to Chaucer, makes it much harder for us to respond to the world in this magical way. |

[Above] Kuta Moon. (Photo by Geoff Fox, 2002)

By 1997 the extraordinary courage of Sipon's husband had brought disaster to his family. The Soeharto government scapegoated Wiji and his friiends for the violence surrounding a government raid on the headquarters of the Democratic Party Of Indonesia. As his friends began to disappear, Wiji left home one day, telling his family he had to leave for a while but would return. Sipon has not seen him again since that year. In the aftermath of her husband's disappearance, Sipon and their two children were the victims of army harassment, mysterious night time stalkings, and persecution based on the doubtful presumption that her husband was a communist. She described one interrogation like this:

MEN IN UNIFORM

men in uniform

thick green stripes

& jungle brown

pick up this mum

& her staring little son

She is turned in questioning

surrounded up by gun,

rounded butt of massed baton

& a single sweetened cup

of cheap tea cooling down.

Facing life with 2 children and without a husband, Sipon works long hours as a tailor to make ends meet and do much more. Despite the fact that she has no formal education beyond primary school, in the past five years Sipon has met the wife of the then Indonesian President Wahid in the presidential palace, met the head of the parliamentary committee for missing persons and met the minister for justice, whom she successfully invited to attend a theatre group founded by the families of missing persons. It is extraordinary for a woman from a low socio-economic group to meet such important and busy people in a hierarchical society like Indonesia. The extremely conservative justice minister even accepted a dinner invitation from the activist actors. Another Sipon poem:

[Above] Sipon and Daughter at a Reading in Semarang. (Photo by Geoff Fox, 2000)

MY CHEST THUMPS

My chest thumps

my feet shake

& I wake

with a start

from our midday nap.

Some voice pumps

& orders snap

looking for my husband

like an object on a chart

looking for my gone man

with a hard dark snarl.

I hear a crowd of feet

entering my house:

no one stops to ask

just herd in to blast:

"Lady, where's your husband?

Where does he do his writing?

Where is his library?"

I'm silent.

I'm not fighting

their lead idolatry.

I'm waiting for my husband.

But 8 of them take turns to pass,

tip the books & cupboards up

like children spreading toys.

He left after a bashing

in the course of army business

& I want to keep on asking,

"Why can't they respect us?"

but I saw they were lodged

unturning from their jobs

No thought or feeling anymore.

The Almighty Law.

[Above] Sipon at a Reading in Semarang. (Photo by Geoff Fox, 2000)

Sipon wrote very little poetry before her husband disappeared. Losing him was an extremely traumatic experience: she has never had the opportunity to grieve and heal through the ritual of burial, because no one knows for sure whether or not the loving father of her children is still alive. In the initial period after Wiji's disappearance, Sipon and her children were feeling extremely depressed and powerless. I saw a very clear potential for Sipon to create powerful poetry from her experiences. No amount of education or artistry can surpass the emotional power of reality to inspire. Furthermore, in 1995, Wiji had told me that he believed Sipon had the ability to write poetry.

Sipon tells it like this: "After my husband disappeared, Geoff kept on encouraging me to take the plunge and write. He said, 'Writing may give you a little more strength to face all these problems which you do not deserve.' He was right that my two kids and I did not deserve this. We were paying a terrible price for the courageous political risks taken by my husband. Sometimes I just could not write because of all the problems I was facing. It felt like my right brain could not handle everything I needed to write about, all the problems I had to face. My left brain was pushing me to make a living for my kids. When I did not have the will to write, Geoff kept reminding me, "It takes work. You have to work at it".

One of the poems I wrote was called "Godaan" ("Temptation") about the hypocrisy of a soldier who came to my place out of uniform and tried to ask me out on a date:

GODAAN (temptation)

he tries me out.

I'm invited on a date:

I'm silent

he comes again

in his blue jeans

& open shirt.

wants to ask me out:

I'm silent

he comes again

in shorts

to get me to aerobics:

I'm silent

I am not a bitch on heat

I do not want to prostitute

I'm silent

I'm silent

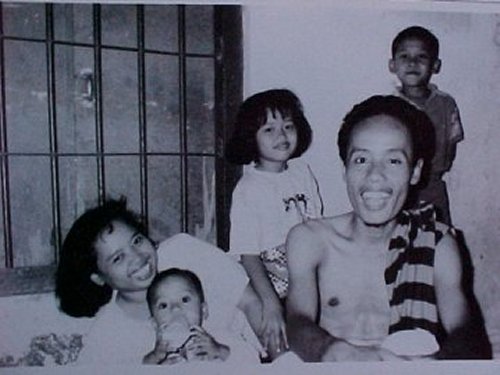

[Above] Sipon and Wiji with their Children. (Photo by Geoff Fox, 1994

All I wanted was for my husband to come home. But now I realize that the exercise of writing down my thoughts and experiences prepared me to communicate more confidently when facing other challenges.

In the past two years I have faced a second major crisis in my life. Someone with money has claimed to own the land where my house is built, and the houses of many of my neighbors. There are documents which support this claim. At first we were all very isolated, scared of the threat of eviction & not talking to each other. But as I investigated my own problem, I gradually learnt about all the others. Some of my neighbors wanted to burn down the house of the rich citizen. I persuaded them to pursue a non-violent approach. Eventually we have achieved a compromise agreement allowing us to buy the properties at way below the market value.

Writing poems helped me to overcome my depression and helped me stop feeling powerless. Then I was better able to organize my neighbors and not be overawed meeting politicians and bureaucrats. In turn I have found great strength in the gentle solidarity of all my wonderful neighbors." That is how Sipon tells the story of her poetry.

|

Wiji once told me that, despite his considerable success as a poet, he did not care about poetry for its own sake. What he cared about was communication: the solution to the intellectually crippling sickness of silence on which Soeharto's tyranny depended. In her own less confrontational style, his wife has carried on his work of facilitating communication.

She has worked on the basis of community engagement. I think her poetry has a type of purity which is very difficult for poets who immerse themselves in literary or academic goals. She does not worry about how clever her writing is; all she needs to do is tell her story. Her daughter Wani also writes poetry. |

[Above] Amien Rais at Boyolali. (Photo by Geoff Fox, 2002)

For me, Indonesia has been a place where poetry is truly engaged with life: my most exciting performance occurred in September 1999. At this time many Indonesians, who had believed decades of Soeharto government propaganda, perceived the Australian peace-keeping force in East Timor as something close to an invading force.

There were frequent demonstrations outside the Australian embassy in Jakarta. Molotov cocktails had been thrown and gunshots had been fired into the building.

On the domestic front, Indonesians were approaching the final stage of the most democratic presidential election they had ever held. No candidate had achieved a majority ... Megawati's party had 33% of the votes and Habibie's had 26%. Amien Rais, with 7% of the vote had nominated the liberal muslim cleric Abdurrahman Wahid whose party had achieved 12% of the vote. In 1997, Amien was the one who had stood up to Soeharto.

At a prayer meeting in early September 1999, Wahid finally put an end to speculation by accepting Amien's nomination. On the same evening, Amien and I were a duet reading a poem called "Ya Salam."

YA SALAM

(invoking ultimate prosperity, this poem revised after 12/10/2002)

I am an Australian

but my home's been Indonesian

because the people are my friends

living words of satisfaction,

"La ilaha illallah.

La ikraha fiddin."

(There are no gods as good as God.

There is no force in faith.)

Most Indonesians live in peace

which this world can't see

because the dark's so bright ...

... I pray we can all cross

our Timor sea of fear

over there and here

to re-ride the waves of Kuta.

I want to go home.

[Above] Evening at Kuta. (Photo by Geoff Fox, 2002)

This man, showing his son the waves of that still magnificent beach at Kuta on the twentieth of September, 2002, is typical of the overwhelming majority of Indonesians who are appalled by and ashamed of the horrific violence inflicted on visitors on October the twelfth. Hopefully this calamity will lead to a better relationship with our huge neighbor. The long-suffering people of Indonesia carry a simple wisdom that I believe too many Australians have lost. You can read it in their faces:

I've been blessed by the time I have spent in Indonesia. And confused. And planning to return. Go there if you can.

Poems "ya salam", "Indonesian chaos piles" © Geoff Fox. Transcreations and translation from Sipon © Geoff Fox 1994-2000 with permission of the Indonesian writers. Drawing © Geoff Fox.

About the Writer Geoff Fox

|

Geoff Fox is a Melbourne performance poet. For 7 years he has focused on the work of Indonesian women poets, performing with singers at many Melbourne venues including Monsalvat, Chapel off Chapel and Revolver. People with whom Geoff has performed include: Amien Rais (current chairman of the parliamentary body which elects Indonesia's president and which impeached Wahid), Neno Warisman (who sang to Mitterrand and Reagan when they visited Indonesia), Arief Budiman (professor of Indonesian studies at Melbourne University), Tim Costello (president of the Australian Baptist Union), Robert Mate Mate (who was an indigenous story teller from Queensland) and Peter Neville (a percussionist who has toured with the Electric Light Orchestra and Elton John). His poems have been published in Overland, Mattoid, Northern Perspective, Fremantle Arts Review, in New Zealand in Spin, in the UK in the Global Tapestry journal and in the USA, the California Quarterly and Northland Review. Geoff Fox's epigrammated drawings have also been published in Overland, Northern Perspective and Mattoid. Geoff is currently focusing poetically on work kicked off by asmaulhusna - the 99 sufi names for the object of worship. He is also a midwife. |

[Above] Photo of Geoff Fox by photographer unknown, 1995)

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.4 (September, 2001)