BREAKFAST WITH MLLE JOSETTE

By MML Bliss

[Above] MML Bliss with Chris Mansell at Wagga Wagga launch of Moonshine. (William Sturgess, 2002)

After Incey Wincey Spider, Little Miss Muffet and Mary Had a Little Lamb, my earliest memories were of skipping rhymes - she's got the legs of Betty Grable, she's got the wiggle of Mal Monroe, she's got the curly hair of Ginger Rogers and a face like you know who ... Sabrina Sabrina don't forget Sabrina. It didn't matter that I didn't know who Betty Grable or Marilyn Monroe were. Everybody knew who Sabrina was and in the rhyme it meant that if you had breasts big enough to jiggle, you were too old for skipping. Then, there were the seamen's shanties that my father recited when he'd had a few too many drinks and Mother (never Mum) shooshed him with "not in front of the children".

Grandad would sit me on his lap and read me western magazines about gunfighters and grizzlies, cowboys and caribou, wagon trains and frontiers. He read me the stories of O. Henry and Zane Gray, and the speeches of Winston Churchill. Along with this odd mix he would let me try to read the sports pages of the Daily Express to him. The first words I learned to read were White Horse Whisky, because they were written on the side of the jug he topped up his glass with.

Grandma sat me next to her on the couch and read me the Bible with such tenderness and sang hymns with such fervour as she vacuumed that I was captivated. My Uncle Bill read me Autocar and Motor Cycle Monthly with passion and I could identify Beezers and Triumphs, Austins and Morrises the way small boys identified trains and aircraft, and little girls knew the names of crooners and film stars. Uncle Bill took me into his tiny, paraffin-heated shed and showed me how to whip ferrules onto fishing rods.

Mother read me articles from Nursing Mirror, Peter Pan and the Water Babies, all of which made me cry because they showed a life so hard, so cruel, and they were so difficult to try to read for myself. She read me Lorna Doone and Jane Eyre. She thought we should "know the classics", and I suspect that she was reading them for the first time when they were inflicted on my three-year-old ears.

An aunt gave me a Grimm's Fairy Tales when I was about four - before I started school. I lay in bed at night with a torch under the covers being terrified by goblins, boys who turned into geese and girls who were forced to spin straw until their fingers bled. There were few books for children in our house, although my sister had one called Kandy the Koala Bear and I can still remember the whole book. Other memorable titles were Heidi, and all the sequels, The Secret Garden and Wind in the Willows. Mother knew Hiawatha by heart, and I was very happy to spend bedtimes on the rhythmic banks of the Gitche Gumee.

|

Mother put records on the gramophone for us. It had needles that blunted after two or three playings of old seventy-eights, but we listened over and over again to Sleeping Beauty and Rose Red and Rose White. Small wonder that I became a poet! Extremes could not surprise me. Years spent fishing with my father had taught me to be absolutely silent and still. He showed me how to wait near hedgerows and on river banks for a glimpse of a rare bird, an otter or even a vole. Together, we saw owls, badgers, hedgehogs and I learned to identify wildflowers and trees. He gave me a small book called The Hedgerow That I Know long after we'd left the hedgerows that we knew. I cherished that book for decades, until it was lost in a house fire in Tasmania.

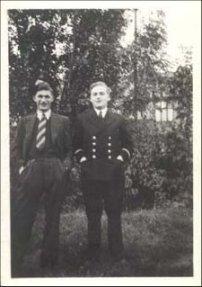

Dad had been on two ships that were torpedoed during the Second World War, and as well as this quiet, gentle side, he could become enraged and violent for no apparent reason. As an adult, I came to understand something of the trauma of combat. |

[Above] The Poet's father, Dean Boult (in uniform) with his brother Stan (photographer unknown, 1940)

As a child, to whom nothing was explained, it was bewildering, frightening, and I can remember wondering whether my father was some kind of ogre disguised as a man. Mother simply told us he was mad. For a long time I believed her and spent less and less time with him.

My mother had been a nurse in London during the war and had been in Guy's Hospital when it was bombed. She was almost as erratic as my father. I wish I had known more of their lives, but we grew up in peace-time, we didn't know how good we had it, we knew nothing. I wanted to learn everything.

Readers of my work should never forget that I grew up near post-war Coventry where food was still rationed; people grew as much food as they could. Children were issued milk and orange juice by the government. Everywhere I went there were shells of houses and bomb sites covered with a pink-flowered weed we called Marshmallow. My paternal grandmother still had an air-raid shelter in her backyard which was a magnet to small children and which we were forbidden to play in. Nobody explained to us that this was a fearful place, a place where people hid from bombs during the blitz. Unexploded shells were commonplace.

We lived in a village, because my father was originally from a rural area and the family land had been appropriated during the war and never returned. All this I had to work out for myself. The chant "you don't know how lucky you are" was true. We always had a Mademoiselle to speak French with, we had a huge rocking horse named Rainbow. We were absolutely indulged in many ways, but we were never really talked with or listened to. Mother told us that children did not have moods, or feelings. I have rarely written poems about this part of my life. The village we lived in had once been a Roman town and we were descended from its original inhabitants. We were English through and through, not Anglo-Saxon, English. We were privileged, I realise, now. This curious and ordinary upbringing echoes through my poetry. I was nine in 1960 and it seemed the whole world changed.

This, then, was the context of my early years. My cat, Sooty (how original!) was the subject of my first poems. Then various other pets, especially the donkeys which my mother bred for seaside and fairground rides. One very early poem that stands out was about the tapestry that hangs behind the altar in the new Coventry Cathedral.

Somewhere along the line I started to read poetry. A.A. Milne, Lewis Carroll and Hillaire Belloc were favourites. Amazingly, I loved A Midsummer Night's Dream at an age when my friends were reading Enid Blyton. Of course, I was given various books by relatives at Christmas and for birthdays. I won books as prizes at school; by the time I was ten I needed another bookcase which I remember begging for until finally my father knocked one up out of old packing cases. Mother refused to have it in the house, so I simply moved out to the shed and did my reading there. Or in the woods of Combe Abbey where I would sit for hours so quiet and still that squirrels would come and take birch nuts from my open hand.

[Above] MML Bliss launching anthology of youth writing, Take it as Read, Wagga Wagga City Library. (photographer unknown, 2002)

Then, as if out of nowhere came the Beats, Roger McGough and Brendan Behan. I recited poems into my hairbrush as often as Mother sang along with Perry Como records. The old gramophone had been replaced by a hi-fi. This was not for the children. We could watch tv, which was a huge piece of furniture in a polished cabinet with doors. Popeye cartoons had limited appeal. I continued to read.

Poetry and poets were always part of my life, rather than just books I read and the writers who wrote them. I read plenty of novels, devoured anything about the natural world, being especially fascinated by snails and their behaviour, migratory birds, owls, otters and any kind of tree and the spreading of seeds.

Poets were romantic, mystical, powerful and seductive. I ploughed through Childe Roland, Walter Scott, Pilgrim's Progress which counts as poetry because of its powerful allegory. I adored Baudelaire, Verlaine, Essenin and as many Irish poets as I could lay my hands on. They were all men. They were all tragic. Poor Shelley had me in tears. They were so unlike anyone I had ever known.

I think I believed that all poets were men until I stumbled across Anna Akhmatova, and later, Sarojim Naidu, Denise Levertov, Emily Dickinson and Dorothy Parker. Here were women who were talented, articulate and above all, inspiring. It occurred to me that I might be able to be a poet, too. To this end, I filled dozens of notebooks with my attempts at poetry. (How I wish I had these notebooks, now. There might actually have been something worthwhile in them.)

|

It seemed to me that if my poetry was ever going to be more than scribbling, I had to learn how to write it properly. So, I began to copy the poets whose work particularly appealed to me, as well as those whose wonderful words were delivered up in strangely stressed monotones by the teachers at school. I learned how to write a Shakespearian sonnet by copying Shakespeare, a villanelle from Dylan Thomas, rhythm and metre from W.B. Yeats. I was a sponge who mopped up poetry wherever I could find it, and squeezed out of myself a grubby kind of verse. It was England. The Swinging Sixties. |

[Above] Jenny Boult with son, Dan, Warwickshire (Stan Boult, 1986)

Instead of swooning over Herman's Hermits, the Dave Clark Five or Freddie and the Dreamers, my record collection was made up of an assortment of imported vinyl. (The Mademoiselles!) Stacked in an old milk crate were Howlin' Wolf, Robert Johnson, Sonny Boy Williamson, Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin. The home-grown product included discs by Dusty Springfield, The Who, The Kinks and anything by Eric Clapton (whom I still believe I could have made happy, if he hadn't preferred blondes.)

It was a time when youth culture ruled. I hung out in coffee bars and basements, listened to poetry, the blues, American folk music (so different from Greensleeves) and watched primitive light shows stoned on amphetamines. It goes without saying that I was a precocious child. It was easy to look older than twelve with make-up, a hair-do and an attitude.

My favourite painter was Max Ernst. I adored the surrealists. My mother ripped down the Dali posters on the shed walls with the comment that they were the daubs of a sick mind. Warhol's soup cans were allowed to cover the cracks.

I remember seeing a documentary on the life and assassination of Gandhi on tv. There was so much going on - it was a Happening time. Just as I was beginning to find myself a niche in the world of sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll, my parents dragged an unwilling fourteen-year-old to Perth, Western Australia. The first I'd heard of it had been a visit to Australia House in London, where we watched a film and a man asked me if I was looking forward to going. My face must have been a replica of Eduard Munch's Scream! Australia?

Later, I was soundly thrashed for spoiling the family's chances of assisted passage. The map was a horror story. There were no towns or villages - just one black spot, Perth. The ship out was fun. There were lots of people my age and a disco. There was a small library on board, and I read everything I could about Australia. None of us were really sure what to expect at the other end. People told us stories of kangaroos tied up on the wharf and savage aborigines who camped out in suburban backyards. The reality was worse than anything I could have imagined.

The light hurt my eyes, the sun burned my skin, the radio stations played music that was a decade out of date. There was no fashion. People wore flip-flops and called them "thongs". Grown men wore shorts with knife-edge creases, dress shirts and ties - and horror of horrors, long white socks and school shoes. Girls wore clothes more suited to my mother than to me. There were no real shoe shops and I was expected to go to stomps on Saturday night and go-go dance with other girls. What era were these people living in? What had I done to be transported to such a place? Borrowed a pair of my mother's nylons without asking? This was Punishment.

My parents had stolen me away from all that was familiar. I often think that I, like many other immigrant children, am as much part of a stolen generation as aboriginal children who were taken without their consent and expected to assimilate into an alien world.

This was the stuff of poetry. Kris Hemensley once described a collection of my poetry as "the poetry of plaint". No wonder!

[Above] MML Bliss with David Gilbey, Christine Ferrari (in purple jumper) and others, Wagga Wagga Library. (photographer unknown, 2002)

I hated school and wagged it most of the time. I sat in the reading room of the British High Commission and devoured newspapers from all over the world. The Left Wing press became my escape from the hell I found myself in. Marcuse, Bakunin, Mayakovsky, Rosa Luxemburg, Jerry Rubin became my closest associates. The poetry of protest spoke to me and for me. I copied Ginsberg's "Howl" and called it "Underground". It was about conscientious objection to the Vietnam War. It was about my English friends who were still rotting their brains with speed and pints of bitter. It was painful.

My parents were like different people. Things were not well with my world. This was worse than Brave New World. Had we really exchanged our beautiful old maze of a four hundred-year-old house in the soft lit countryside of leafy Warwickshire for a quarter of a suburban acre with a single-brick bungalow on it?

|

There weren't even enough bedrooms to go around, let alone a playroom, attic or outbuildings that I had so glibly called a shed. When I did go to school, I half-listened to lessons. The French master's accent was appalling. Had he never spoken French with Parisians? I surreptitiously wrote poems, or notes for poems, instead of copying from the blackboard, trying to make sense out of the situation I found myself in.

These scrappy efforts were passed around the classroom under desks, like love letters. Girls sighed and boys cringed. Until one day, Mr. Clark asked to see what was so much more interesting than the Battle of Pinjarra. The poem was called "Isolate", a piece I'd spent at least a fortnight writing and rewriting, refining. It was an original - no copied style. |

[Above] Jenny Boult from Hot Collation, Penguin Books Australia (sculptor James, 1993)

It was about a crippled child in a white room who imagined the world outside on the walls of her prison. It was pure and it was mine. Now it was in the hands of the enemy, a teacher, albeit a card-carrying member of the Communist Party of Australia. I was terrified he'd read it aloud. I tried to turn myself into the three wise monkeys. Speak no, hear no, say NO NO NO!

Mr. Clark read the poem silently. He obviously read it again before he asked, "Whose work is this?" Work! He recognised it as work. Someone in the class yelled out "Whose do you think it is, sir?" Shut up. Shut up. Idiot. Every kid's eyes were on me. I'm certain that my face was redder than the Worker's Flag. He knew. He just knew. I'll always thank him for not saying anything other than "If the poet would like this returned, please see me after the history lesson." That was the longest forty minutes of my life. When I went to ask for my poem back, he showed me a couple of places where "and" could be deleted. That was all. There was no criticism, no reprimand. Wow! Had I ever been granted a reprieve! Thank you Mr. Clark. Thank you.

Last night I watched a movie called "Never Been Kissed". The Drew Barrymore character Josie, kind of reminded me of myself. I didn't wear braces or have a distinct lack of fashion sense, but I was too bright and too well-read to be really popular. Instead of making a total horror movie of high school, I became a bad girl. You know the kind - all promise & no follow through. When the other girls were bopping with J.O'K, I was smoking dope and listening to delta blues and anything that came out of San Francisco. While other girls dressed like hippies and might have secretly listened to Janis Joplin, I made love, read Gandhi and Timothy Leary and had a dope leaf tattooed on my shoulder. When I see how those popular girls turned out - mainly nurses and teachers, or public servants who worked their way up as far as the glass ceiling, it makes me really glad I was bad.

In senior high school I was one of a group who called ourselves "the gang of four". It goes without saying that the other three turned out to be a teacher, a public servant and a career housewife. Maybe I was the only one who truly achieved what they only ever dreamed off. I lived the dream before it became tv sit-coms & the catch-line of a radio announcer who should never have been let loose on the airwaves. I mean, there was the Big Bopper, the Night Stalker and I had already grown up with Radio Caroline by the time I was thirteen. Who were these people? When I read The Second Sex in fifth year high school and wrote a paper on it as a biology assignment, most students sniggered at every timid mention of homosexuality. Female orgasm and feminine intellect were so outre that everyone thought I was a lesbian! This in spite of the fact that I had guys hanging out in cars every day waiting for me to come out of school. That most of these guys were already university students or apprentice motor mechanics only added to my strangeness. Suddenly, the popular girls wanted me to hang out with them. It was because I didn't care about them, their chain store charge cards or personal dressmakers. Why should I? They all looked and sounded exactly the same. They were constant reminders of what I wasn't, what I hoped I'd never be. Clones of the system. I was into the Counter Culture, a rebel with a cause. Satyagraha wasn't just a skinny Indian guy in a loincloth, it was a way of life, of thought, of truth, of searching for what was meaningful.

|

It was about experimenting with everything until I worked out what was right for me. I spent a lot of time haunting libraries & reading one section at a time. I went to Dorina's Discotheque and danced weekends away, and still managed to pass Matriculation. It had not occured to me that I might be awarded a Commonwealth Scholarship, enabling me to go to University of WA. My parents did not like the idea much. Dad told me to become a hairdresser (thinking of a secure financial future), Mother thought it all unnecessary and thought I should learn secretarial skills first. "You'll be able to charge for typing up essays and so on." Yeh, right. I kept on with my job as a trainee pharmacy assistant until a few days before O-week. The above lines are some of the unwritten poems, and the silenced poems of my childhood. |

[Above] MML Bliss at the launch of Legend!, Conford Press, Hobart, Tasmania (Tim Thorne, 2002)

The discovery that writing original poetry required more effort than waiting for the lines to flow perfectly and manifest into corruscating verses of their own volition, was like learning to talk to the Mademoiselles. It took practice - they spoke so fast, their lips dripped with the latest slang and the language of the magazines they read bore precious little similarity to the French we studied at school - Moliere and de Maupassant. One year, the Mademoiselle came from Narbonne and she twanged around the house like a country & western singer. Dad adored her, Josette - the only Mademoiselle who ever had a name.

Mother said she was a slattern, and we should have kept with Parisiennes. Speaking with Josette was more a new language than a differently accented speech. Like the difference between a ballad and a sonnet. The Muse enjoys speaking in unfamilar dialects, rustling whispers or bolts of lightning. There comes a day when suddenly meaning becomes clear, you understand how to say what you want to convey. It's a two-way thing.

In order to speak and be heard, you have to have something to say. The Muse is that moment when everything gels. Then, her task completed, she disappears again. It's up to you to act on that moment, to commit the words to paper. To examine them and speak them aloud. Lesson one, then. Listen, understand, evaluate, reply.

Lesson two. Write it down. It will be there in the morning, just like a Mademoiselle. Lesson three. Be patient. Fear nothing. You are so big that you can afford to give away this small part of you. Be mean. Be polite. Smile and you'll be forgiven almost anything. The thought police are everywhere. Lesson four. Ignore them. Learn your style and range within it and stretch it as far as you can. Walk on the edge that rims the abyss. As when chatting over breakfast with a mini-skirted Mademoiselle, it's essential that you know all the rules. Then, you also know which ones to break.

A poem rarely flows out of its own imagination, if it did, there would be no poets. Poetry could be pulled out of the air like a drowsy blowfly, and probably sound much the same. I learned about metaphor and imagery from reading other poets and copying their various styles. I learned that poetry is an art, but it's also a craft which needs constant practice. It isn't just about skill and a dazzle of technique, a pyrotechnic display of clap-trap. The poem must come from the heart. Even the most simple throw-away verse is valuable. When we own our clunkers, we learn to watch out for them.

We can learn from what has gone before, but ultimately, it's down to us to speak directly and meaningfully to an audience. Whenever I sit down to write, I still say "be true to yourself" a few dozen times before I commit even that first draft to paper. I remember the words on grandad's jug. White Horse Whiskey. Every poem is like reading the words for the first time. "Grandpere, il boit." And somebody is always there to give a new slant on the familiar. I still feel despondant, angry, annoyed, etc when I find that my best poems are rejected by some editor or another. Then I think, well, editors are a bit like au pairs. They come and go. The poem lasts forever.

About the Writer MML Bliss

|

MML Bliss (Magenta Bliss) was formerly known as jenny boult. She changed her name for personal reasons. She was once told in the post office of a country town in the north-east of Tasmania that she might be jenny boult on the mainland, but in Derby, she was Mrs. Smith. Poems, stories and plays by jenny boult and MML Bliss have appeared in magazines, journals and anthologies in Australia and overseas. MML Bliss has been translated into French, Swedish, Norwegian, Urdu, German and Italian. MML Bliss was awarded a Booranga Writers Fellowship, Wagga Wagga, in 2002. She lives in Launceston, Tasmania. MML Bliss is available for readings and workshops in schools and community centres. |

[Above] Photo of MML Bliss by Tim Thorne, 2002.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.4 (September, 2001) |