WRITING AND DIRECT ACTION ON AUSTRALIAN ANIMAL FARMS

By Coral Hull

[Above] Bunge piggery, Corowa, New South Wales, Australia. (Photo supplied by Patty Mark, year unknown)

"We stared into the faces of the tortured and insane, into the eyes of the next and the next and the next and the next until even to us the screaming agony of those animals became merely a process. There is no right way to be in the world if you have no heart inside you. How do I know that it is wrong to be cruel? No one has set the rules. I just know that it's wrong - that's all. Hell is the absence of Love. As I looked out across that huge industrial landscape of the factory farm I knew that I was entering Hell. I was on the edge of my sanity in those places. I was confronted again and again and again by my own powerlessness, by what I was unable to rectify, 13 hens came out with us to safety while 20,000 were left behind. I prayed to God to bring my mind back, because at some stage had I laughed? I had become so numb, someone could have put a cigarette lighter to my cheek and I would not have responded to it. My heart was no longer there. It had fled in horror." - Personal Journal, Coral Hull, 1997

I first began to be involved in direct action and animal rescue operations on Australian animal farms during an 'Our Hearts Are With The Hens' roof demonstration on Valentine's Day 14/2/96, at Victoria's largest battery hen farm, Happy Hens Egg World in Meredith. The action, which was conducted by activists from Animal Liberation in New South Wales and Victoria at the time, resulted in widespread national publicity for the plight of battery hens and the arrest of a number of activists present, including myself. I had not known what to expect as I left Melbourne late one night, and was driven to the location with people I barely knew. Once out in rural Victoria we were dropped off at the battery hen farm. Soon I began to make my way across the huge dark paddocks reeking of fertiliser in the early hours of the morning, along with the other activists, with the intention of saving battery hens from pain and suffering at the hands of animal farmers. As a concerned person I was relatively new to this type of action or protest. As a creative thinker I was to be deeply impacted by what I experienced, both as a result of my participation in this protest and by working with various individual activists over a two year period. The literary and art world with all its conceptual concerns faded into obscurity, as I was faced with animal agony and human brutality on such extreme levels as to render me into a state of shock.

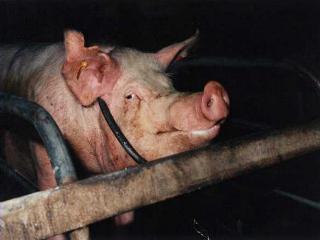

[Above Left to Right] Australian piggery, Victoria, Australia. Parkville piggery Corowa, New South Wales, Australia. (Two photos supplied by Patty Mark, unknown year). [Below Left to Right] Bunge Piggery, Corowa, New South Wales, Australia. (Two photos supplied by Diana Simpson, 1996)

The inspiration for my participation in this first onsite event was the viewing of some undercover footage taken by activist Diana Simpson inside the sheds at this particular farm, the now infamous Happy Hens Egg World in Meredith, Victoria. On the video, Patty Mark, founder of Animal Liberation Victoria, was reaching into the cages and lifting out injured and sick and dying hens. One of the hen's beaks was so corrupted that it was split into three separate pieces that just jutted out of her face. There would be no movement from this bird at all in order to eat or drink. Her eyes were half closed. She was emaciated, suffering severe feather loss, her comb was limp and she was dying. 'Just look at her!,' Patty exclaimed above the raucous screams of 20,000 desperate hens. Then turning to the hen she said, 'We've got to get you to a vet.' It is still difficult to accurately describe what is was like to go out onto my first industrial animal farm. The following excerpt is a section from a work in progress titled Battery Hen:

"... I do not know what it is like to be a farmed animal, or to have my family tortured and murdered, or to never see the sunshine or feel the rain, or to be shackled so that I cannot turn around, or to stand screaming out on the bodies of the dead, or to be cut into by wire and steel chains, or to have every bone in my body broken while still alive, but I do know what it is like to suffer, to be unloved and to be alone, before you go out on a rescue there is a time when you are very alone, and you must sit with this aloneness, in order to be centred and still within yourself, you are about to go from one dark world into another darker one, even the scene down the street changes as this perceptual transition is being made, the bookstore, the café, the restaurant, the galleries, the theatre and the various décor of inner city life begins its cessation, even before you leave, you are somehow already lost from this world as another world takes hold, as soon you are picked up at your door or you drive to a location in your own vehicle, and you are amongst the other activists, ...

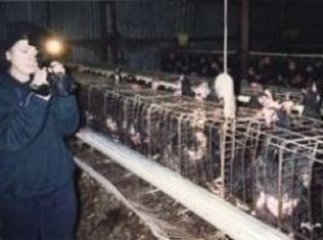

[Above to Right] Montalto's poultry farm, Epping, Victoria, Australia. (Photos supplied by Patty Mark, late 90's)

"... I have rarely felt as alone as just before I went out onto that factory farm, I didn't bother to contact anyone I knew, I just felt that I had to hit a certain level of aloneness, I thought of the hens, pigs, cattle, sheep and the millions of other animals mistreated by Australians out there in the night, and of the psychological darkness that I was entering, there was nothing to say, I felt fearful and alone, but not nearly as alone as those birds must have felt, so many unknown and unloved by this world, three or two crammed into a cage the size of a notebook, thousands of cages in tiers and layers, in monstrous airplane hanger sized sheds, they are far more alone than I would ever be in my lifetime, sometimes looking into the stars can make you think of your own aloneness, but I think it would be more lonely for those hens, crammed in piles on top each other, and having never seen the stars, moon or sun, having in fact seen nothing but the insides of their own suffering and insanity, ...

I got into the van with the another activists who came and picked me up, the drive out along the freezing highways was illuminated by hundreds of whirring industries, too harsh for human and non-human animal alike, and too dark for philosophy, analysis or compromise, as it is said, 'good intentions aren't good enough,' tonight it was all about direct action, that is all that mattered in the end for the sick and dying, for the suffering who are suffering now, as I write this, as we speak, as we write poetry and attend literary functions across the country, side by side our lives concur with the suffering of others, so how often and how must we blind ourselves to this, for even I must blind myself to this in order to continue, because the suffering is so monstrous as to be unfathomable, on the night of my first action, the moon was full so the paddocks were luminous, as the single file of activists including myself now half-revealed, made our way quickly and quietly across it, Fiona grabbed my hand and whispered, 'we will always remember this night,' as this was my first time out on a factory farm, I didn't know what to expect, it was completely unknown territory, I only knew that whatever happened we were here for the hens, the other activists surrounded me, ...

[Above] Happy Hens Egg World, Meredith, Victoria, Australia. (Photos supplied by Patty Mark, 1996)

"... my first steps out onto the paddock of the huge industrial wasteland were like jumping onto the face of the moon, there were giant potholes and clumps of dirt, every step was in darkness with thistles or wire, or fences that could be run into or caught on, we wore dark clothing that no-one could look into but that we could look out from, and I thought of everyone's eyes, wild and determined, and the combination of empathy and fear that existed there, the heavy boots, dark clothing and the ice cold night on our backs, in front of us the darkness was huge and infinite, the idea of what was being done to those animals endless and as yet as unfathomable as space, as the sheds rose up in the distance the stars became their backdrop, everything took on the immense unreachable distance of a galaxy, from there the sounds of humming whirring machinery came into being, Fiona said, 'they are the fans, and the lights that go on and off are sensor lights, they detect movement, 'then she paused for a moment and it was as if the night machinery paused with her, 'listen,' she said, 'can you hear them?' I strained my ears for a moment, then I heard them, the low approaching wave of a huge tide, relentless in its approach, the screaming of thousands of birds waking up, to die and to be fed, ...

" ... in the foggy night the stench of ammonia, hen shit, corpses, unknown chemicals and finally the hideous screaming that came into focus, from nine enormous sheds the size of airplane hangers with 20,000 hens suffering inside every one, we took ladders and climbed up onto the roof, the sheds looked alien, with splices of light travelling down between each one, Fiona said, 'that's the sensor lights going off, it must have been a rat or something', the lights were lighting up machinery and parked trucks at intervals, there was the movement of different machinery left to run on its own all night out in the dark, the cold harsh industrial material, it was like looking out upon a huge city where everything was foreign and potentially harmful, and yet where everything in the world was suddenly also in your hands, already our sense of responsibility and purpose had begun, and fear of failure had ended up being greater than my fear of death, we carried eye-droppers and cotton pillow cases and the soon enough came the reward, the warm frail bodies of the gentle hens lifted from the tiny cages, ..."

I worked with other activists out on farms for two years during 1996 - 1998. Since childhood and over the years I have been present at broiler farms, intensive pig farms, zoos, circuses, animal shelters, puppy farms, shooting excursions, a cat farm, fish farm, transportation trucks, cattle farms, sheep properties, crocodile farms, slaughterhouses, deer farms etc. I have also been involved in dozens of individual animal rescues from pelicans to kittens. The latest documentation was of Macquarie Fields Leisure Centre in the western suburbs of Sydney, where trout had been released into the Olympic pool, to be caught and cruelly killed by the public as a fun event for the local westies and their families, with the same event held at Blacktown public swimming pool. It was happening right under our noses.

|

On some days it seemed like the whole of humanity had deliberately set about to consume just about every sentient being imaginable. It was as if our main purpose was to eat the world unnecessarily and to shit it out, and that the purpose of the planet was merely a giant genetically modified food bowl floating in space, that we had the urge to overpopulate, turning everything we consume into human excrement, without conscience beyond what tasted good inside our mouths. This was to be done at all costs and without mercy.

My challenge was not to lose my faith in humanity, hence in myself. It was not to become like the cliched animal rights activists, the ones who love animals and lack compassion for human animals. Australian poet Anthony Lawrence once said to me that he was concerned about what I was doing to myself by constantly attending places such as slaughterhouses. I remember thinking to myself at the time, if you didn't support these atrocities every day of your life by your choice of diet and fish-killing excursions, then I wouldn't have to do what I do. I knew that he was in the majority and I was the minority and that the choices we each made in each moment would have an effect right now on the future the world. |

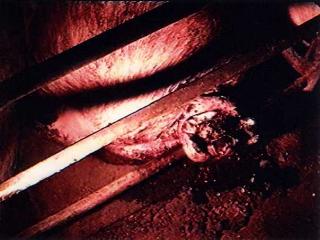

[Above] [Above Left] Wollondilly slaughterhouse, Tahmoor, New South Wales, Australia) (Photo supplied by People Against Vivisection, year unknown)

As an animal rights activist I had a purpose, and that purpose was to minimise suffering for all sentient beings. It was also to educate the public on the issue of animal rights and to abolish the property status of non-human animals. In order to do this I was involved in dispensing information that was meant to inform and persuade an audience. I was also involved in direct action and animal rescue operations. Often such operations were coordinated, focused and tactical in approach and response. Like many activists working in Australia and around the world for the environment, humanitarian causes and for animals, I've been arrested, I've had guns pointed at me, I've been thrown to the ground and kicked in the back, I've waded through manure pits, I've been chased by security guards, I have dug under electric fences, I've suffered from ammonia poisoning, I have been crawling in lice, I've had animals die in my arms and release their bowels on my clothing. I have regularly witnessed such horrendous things done to animals, that I've continually had to reassess everything to do with living in this society. Yet through it all I've saved the lives of at least a few animals. It was only a few amongst countless thousands. But to those animals it mattered.

Throughout my participation as an activist I always remained a writer and photographer perceiving my surrounding environment through the eyes of a creative artist, interpreting specific events in my life and the lives of others - both the animals and the people I worked with. As a creative interpreter I had intentions to record and manipulate this information. Imagination, combined with my emotional interpretation of the environment, more than often began the creative process for me. I am back out at the industrial factory farm again. I am listening to sounds and I'm likening them to something I may have heard before. I am making associations. I am extending metaphors to describe as deeply and as accurately as possible the situation at hand. I am intent on uncovering a truth. When I work as a creative interpreter, I not only participate in the action, I observe my surroundings and how I am feeling. It was, for me, often a very raw and immediate emotional experience, however I nearly always chose not to feel anything at the time. I often remained disassociated as a way of dealing with trauma and taking effective action.

[Above Left] Wollondilly slaughterhouse, Tahmoor, New South Wales, Australia) (Photo supplied by People Against Vivisection, year unknown) [Above Right] Montalto's poultry farm, Epping, Victoria, Australia. (Photos supplied by Patty Mark, late 90's)

The flashbacks and nightmares came later on as I relapsed into my PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder). Often I would jump out of bed each morning to avoid seeing an image of a pig having its throat slit over and over again. I saw many activists burn out around me.

"... I was racing out of shed nine with Fiona Hallam, we each held pillow cases, two hens each, and the smell of Happy Hens Egg World was again beneath our fingernails, in our clothes and through our hair, it was waiting to be rubbed deep into our throats, our nasal passages and our eyes, 'go for it!,' I shouted into the darkness as the farmer's headlights began to race down the hill, 'go for it Fiona, we've set off a silent alarm, the activists were all bolting across the moonlit paddock in the dark, out on these paddocks the moonlight is the enemy and the tree roots are your friends, I never thought that those with good intentions would have to slink around in the dark, we were running with ease as the hen's warm bodies and silence set our mouths into small smiles, we all bolted across the dark field as if we were pieces of darkness that has suddenly lifted ourselves out of the jigsaw puzzle of night to move in solid blocks, then quiet. suddenly several gun shots rang out and I felt a sharp hot pain in my back beneath my left shoulder, then a few more shots were fired as we began to run, and I couldn't help it, but I was laughing, 'they're fucken shooting,' I said,' let's get the fuck outa here!,' I didn't know why I was laughing, I had received news on the internet that activists had been shot at out on an intensive pig farm in Switzerland and that one had been hit in the legs, but we had the hens and with that thought we crossed a border, as we suddenly entered the brightest daylight imaginable, it was still the same field but the light was intense, it was like a field of haystacks, wheat and corn blazing beneath a blue sky, with the sun blazing in each individual object, my first thought was that we would be seen with the hens in broad daylight, I turned to see Fiona next to me, Fiona Hallam with her little bundles of hens, 'where are the others?' I asked her, but they were nowhere to be seen, ..."

"... we kept walking and the sticking mud and manure began to drop off our boots caking the grass as it dried, 'I don't know where we are,' I said 'but I feel happy, don't you?,' 'yeah,' said Fiona, 'I feel as if I have to be here, we kept running and walking at intervals as we usually did, in order to put as much distance between the farmers and the hens as were could, we seemed to come to fields of moving lights and then we saw that there were fields and fields of fat healthy hens out in the sunlight, they were dust bathing and picking at the dirt, ..."

|

" ... I turned to Fiona as we released the hens from the brown shit-covered pillow cases, they walked shyly on to join the others, we were the only shadows on the field and the darkness was dropping away from our bodies like caked-on mud drying, as we moved towards the fields of hens, we turned to each other and it was as if we didn't need to say anything. I saw the back of Fiona's hair had a huge gaping wound, the dried blood mixed with her hair, 'do you think we were shot?' I asked, I mean like really badly shot?' She nodded ..."

After we had spent a night out on a farm, measuring it up for later actions, rescuing sick and dying battery hens or being pursued by farmers, security guards and police, I would often write about what happened directly afterwards in note form at all hours of the morning. It was a way of unwinding before dawn and a couple of hours sleep. The next morning I'd be up early. The new arrivals had to be fed and introduced to grass and sun for the first time in my small backyard in Collingwood, before being placed into the hands of a permanent carer. The next morning the antics of the gentle and disbelieving birds were the reward for pain. I had to scrub every trace of chicken shit off my boots. I can still smell it two years later and it smells like suffering and torture. |

[Above] Happy Hens Egg World, Meredith, Victoria, Australia. (Photo supplied by Patty Mark, 1996)

I have also jotted down notes on location or during an investigation or a protest, but as the notes would indicate, I barely had my thoughts and emotions properly integrated at the time. For me direct action involved a kind of basic and militaristic kind of thinking and not the emotional openness and philosophical pondering necessary for poetry and other writing. While I work well under speed and pressure in regards to my photography, the creation of any artwork for me is ultimately an intimate and private experience. It requires introspection, solitude, empathy and time. It works at a slower pace. Its basic considerations are essentially different from that of organising or taking part in a political action.

[Above Left to Right] Parkville piggery, Scone, New South Wales, Australia. (Photo supplied by Patty Mark, year unknown) Happy Hens Egg World, Meredith, Victoria, Australia. (Photo supplied by Patty Mark, 1996)

I believe that the way of the activist and the way of the poet are two very different ways of perceiving and understanding an experience. Although they do overlap, there always seemed to be a tension between the two ways of interpreting and responding for me. They never really occupied the same space at the same time. Therefore this tension existing between the two was never reconciled. An example of this tension would be in my book of poetry titled Broken Land, published by Five Islands Press in 1997. The writing of Broken Land was where I first really began the creative documentation of slaughterhouses where I was a participant on location, the art forming from the action before my very eyes.

At the time I accidentally ended up visiting a slaughterhouse that was killing goats at Bourke in outback New South Wales. I meant to be looking at an old abandoned knackery (horse slaughterhouse) and was surprised to find once I got into Brewarrina that it was a fully operational slaughterhouse involved in the slaughter of wild goats. I was startled but I went along anyway. The results were soul shattering as I was confronted with the brutal murder of personality after personality, being after being after being. During the couple of hours I was at the goat slaughterhouse, I shifted between the two ways of interpreting such an environment. When I was able to think creatively, I saw a freshly decapitated goat's head with its long shaggy mane of hair swing in the air, whilst being thrown by a worker from twenty feet up. The scene appeared to play out in very slow motion, until I could liken its motion to a galaxy. I then had the thought that trying to imagine the suffering endured by animals at the hands of human beings worldwide was like trying to count all the stars in all the galaxies of all the universes.

[Above Left to Right] Sitebarn slaughterhouse, Bourke, New South Wales, Australia. (Photos by Coral Hull, 1995)

When I allowed myself to feel in order to create, I wished I never had. One of the goats began to scream, in a way that sounded like a man being murdered. This resulted in a sequence of poems about the goat scream. Some of my best writing is often unexpected and comes at some emotional cost. Yet nothing could have prepared me for the final and man-like screams of terror and agony of a desperate goat struggling over and over for his life, as the knife was lunged and dragged into his throat again and again. My blood ran cold for three hours. The male goat is now dead and has been for a long time. But his scream lives on inside my soul. I have never fully recovered from his murder. I see the world as holistic by nature. Therefore while I was there on my own, I believe that in a way we all lost him and that now we must live with ourselves and the consequences of this loss.

The poet side of me knew how to write this down and feel something despite the ramifications. The activist was the person who knew what questions to ask and how to remain undetected and disassociated. Direct action was a very mechanical process that involved analysing my surroundings from A-Z. In this state of mind any factory farm or slaughterhouse looked like a map, where certain strategies are employed in order to achieve a result. That result was to save the lives of animals. There was an immediacy to this way of thinking and acting that gave the sensation of achieving quick results, while creative art seemed to operate at a slower and, at the time, a more frustrating pace.

Another example of this creative distraction was at Bunge piggery in Corowa, New South Wales. Bunge piggery is the largest intensive piggery in the southern hemisphere, torturing over 230,000 pigs at any given time. On this occasion my main concerns for the night were: not being caught before we had done what we had to do, all the pigs that were going to be slaughtered at the on-site slaughterhouse at 6.00am, sliding in pig effluent under gateways, too many electrified fences, very large patches of thistles on an uneven paddock, sub-zero temperatures and carrying the aluminum ladder. After a two hour chase with security where they were unsuccessful at finding us, myself and two other activists Fiona Rees and Diana Simpson had been walking with the aid of tree cover for about 30 minutes. Although we were dressed in silver and grey it was a full moon on a clear night and the only camouflage were the shadows from buildings or trees.

[Above Left to Right] Happy Hens Egg World, Meredith, Victoria, Australia. (Photos supplied by Patty Mark, 1996)

This place was enormous, comparable to a small city. At the time I remember thinking that rescuing animals from such a place for could very well occupy me for many months, perhaps the rest of my life. On this particular night a flock of local wood ducks were disturbed from their night roost, and flew into the air from a stand of gum trees. I was immediately distracted by the heaviness of them and the power of their startled flight. However since we had plenty of cover from the hourly security patrols at this point and a little walk ahead of us, I allowed myself some creative pondering. The silhouettes of the wood ducks were definite and unrestricted, plump and solid shapes in the crisp air. It was a moonless night and a full flood of stars were behind the ducks at lift-off, as they flew a short distance to another gathering of eucalypts. I thought about the kind of vegetation that grows around a slaughterhouse, and if it would be any different from vegetation growing at other places.

Later on, I was to write that during this moment I took out part of myself and I sent it off into flight with the wood ducks. Because I knew that to take everything of myself into that place, into giant sheds where pigs never see sunlight or feel or smell the earth, where pain-crazed sows have lost the use of their back legs, where tormented they slide along on maggot-infested prolapses, where they stand in stalls where they can't turn around or feed their babies and where they are often kicked and beaten by the workers, would be to risk coming out with nothing left of myself. Because to be inside those places you have to say, 'I am insane. I have entered Hell. I'm going to do what I can'. As many activists in this situation know, aside from the lives of a few animals saved and some media acknowledgment of the event, you are nearly always confronted by such enormous suffering and unnamable atrocities that you are largely unable to rectify or prevent, no matter how badly you want to.

|

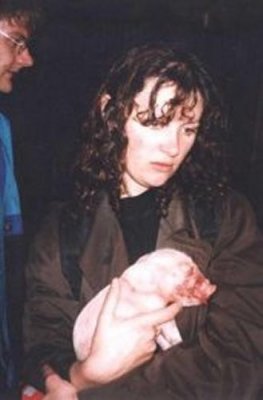

An example of this is when another activist, Debra Tranter, said that the eyes of a trapped mother sow had locked onto hers during a rescue operation, and did not leave her until she left the shed carrying this mother's injured piglet to safety. The suffering sow, like many others, was lame and had to be left behind. Debra remained traumatised and guilt-ridden despite her courage and the odds being against her, because we have to remember that to even enter these farms is illegal. Therefore there is the burden of detection and hence immediate failure alongside the responsibility of rescue, who to take and who to leave behind. For as we know too well, they all want to be rescued and they are all worthy of being rescued. The burden of responsibility while being in a position of powerlessness is excruciating.

Activist and actor Lynda Stoner remembers her legs being covered in maggots, as she chained herself to the sows in solidarity, during a sit-in demonstration at Bunge piggery. Fiona Rees, who was nursing a rescued hen on the way home from a battery hen farm, had the tumor on a hen's eye burst open, after the poor hen tried to rid herself of lice by rubbing her face on the cotton pillow slip. |

[Above] Bunge piggery, Corowa, New South Wales, Australia. (Photo supplied by Patty Mark, year unknown)

Fiona's cheek was sprayed with pus. Like the others who visit them, the horrendous scenes from these factory farms is something I will always carry with me. So on this particular night, with the wood ducks as the focus, I was putting some emotions aside, in order to preserve some part of me that wouldn't have survived in the piggery. This creative expression of my experience afterwards usually involved the documentation of certain events that may have occurred during the action. It helped me to debrief.

When I first became interested in politics I was told that I could do it all through my poetry. At the time I dismissed this as fallacy. I thought, "If only we could save the world just through writing poetry alone and nothing else. But I am sorry to say that we cannot, however good our intentions, or the ethics that exist in our poetry, may be. Simply because right now the animals like these are suffering. Every second animals die hideous and unnecessary deaths, whilst it may take years to get a poem or a book of poems published." I agonised over whether the art world within Australia was political and ethical for over a decade. I used to believe that whoever thought that poetry was political, just because it was poetry, was deluding themselves. I believed that if I was only a poet, I would never do my job effectively, mainly because it is a slower process than is needed to decrease suffering right now. It was the immediacy of cooperative hands at work that got the results, in a crisis situation that presently exists for the victims of torture. This belief was brought about by my sense of urgency and personal responsibility, that somehow I was responsible for situations and events, even when they were beyond my control. This way of thinking caused me alot of unnecessary anxiety and pain at the time. I now believe that short term and long term action on behalf of those less fortunate should occur simultaneously. I also believe we live in such a negative and destructive society that the positive construction required for the creation of poetry is political by its very nature. Poetry is political because it continues to exist and flourish despite the odds. It is an expression of the human spirit that endures.

[Above Left to Right] Rescued hens from Hutchinsons battery hen farm, South Morang, Victoria, Australia. (Photos by Coral Hull, 1997)

Yet while it may be used in order to document and record external and political subject matter, creativity is essentially self-focused. As an activist I had to be focused on animals and the other activists in the group, rather than what I might be thinking about. When I was working as an activist, emotional and creative interpretation may very well have been an unwanted distraction during a tight and risky operation or an emergency or crisis situation, in which we had little to no time for feelings, only for manoevres. But since I can never completely kill the creative interpreter inside myself in order to be completely emotionless, it is a matter of allowing either one to emerge where appropriate. Often on these animal rescue operations emotions were repressed. Then in order to explore my emotions afterwards it was my actions that were relaxed or stilled. While I have found a tension existing between the two, they do not have to remain mutually exclusive. Like many activists I have spoken to, I've often wished that I didn't have to feel at all in those places. Yet no matter how emotionally cut off I've had to be over the years, it is my emotions that originally drove me to save the lives of sick and dying animals. It was my experience and actions that taught others and not my political preaching. It will also be the emotions that drive me to action either out on the farms or to the many other areas where suffering life is in need of assistance in the future, and likewise to then create poetry and other art from simply being present in such environments.

Earlier version of this article was first published in Five Bells: The Poets' Union Newsletter (Australia).

About the Writer Coral Hull

|

Coral Hull is the author of over 35 books of poetry, prose poetry, fiction, artwork and digital photography. Born in 1965 she was raised under disadvantaged circumstances in the working class suburb of Liverpool in Sydney's outer west. Coral became concerned with issues of social justice and spirituality from an early age. She wrote her first poem about a rainforest at age 13. Coral became an ethical vegan and an animal rights advocate who has since spent much of her life working voluntarily on behalf of animals and the environment, both as an individual and for various non-profit organisations. She is also the Executive Editor and Publisher of Thylazine; an electronic journal featuring articles, interviews and visual art of Australian poets, writers, artists and photographers. Coral holds a Bachelor of Creative Arts degree (Creative Writing Major) from the University of Wollongong in New South Wales, a Master of Arts degree from Deakin University in Victoria and a Doctor of Creative Arts Degree (Creative Writing Major) from the University of Wollongong. An extensive biography, list of publications, festivals, interviews, articles and reviews can be found online. Coral currently lives between Darwin and Sydney, with her two dogs Binda (deep pool of water) and Kindi (fire). |

[Above] Coral Hull, Elliot Hotel, Elliot, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.4 (September, 2001) |