BROKEN LAND: A TRIP TO BREWARRINA: SOUND AND POETRY

By Justine Lees

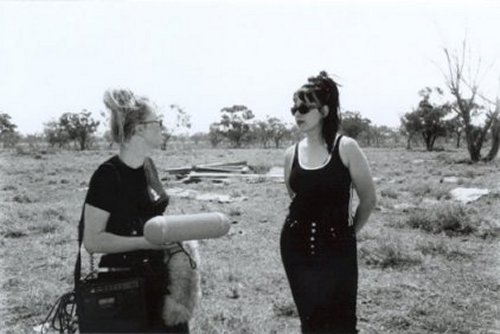

[Above] Justine Lees and Coral Hull recording at Twin Rivers, Brewarrina, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Amanda Shillabeer, 1999)

As part of my job as a producer for the PoeticA program on Radio National I obviously have to read quite a bit of poetry. None, however, has affected me so immediately and profoundly as Broken Land - Five Days in Bre 1995 by Coral Hull. Often disturbing, sometimes humourous but always compelling, these poems create a story that I knew I wanted to tell on radio. But I never imagined I'd be reliving that story. I thought I'd get an actor in to the studio with me in Melbourne to read the poems, then mix in a few sound effects to complete the program. My Executive Producer had other ideas. He acknowledged the powerful nature of the material, and suggested that to do it justice I should go with actress Amanda Shillabeer and Coral herself, to record the poems in the places that inspired them. And so before long I found myself travelling to Brewarrina, in north-west New South Wales.

When I boarded that flight in Sydney early one morning last September, my travels had been more outside Australia than within, and the little I knew about Brewarrina suggested it was not exactly a tourist destination. Suffering significantly from the rural decline, environmental degradation and ongoing racial tensions, it did not sound enticing. Worse, I was the ringmaster of this travelling circus. I was the reason that three people who had never met before, not to mention thousands of dollars worth of recording equipment, were sitting in this tiny Cessna gazing out at the red dirt as we travelled further and further west.

[Above] [Above Left] Justine Lees and Coral Hull recording in an abandoned shack, Brewarrina, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Amanda Shillabeer, 1999) [Above Right] Justine Lees, Coral Hull and Amanda Shillabeer outside the shack, Brewarrina, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Cliff Hull, 1999)

I shouldn't have worried. The three days that I spent in Bre with Coral and Amanda were more rewarding than I could ever have imagined.

Coral has a lifelong association with Brewarrina. It's where her father was born, and to where he returned to live when she was in her teens. During her childhood it was a frequent destination for family trips, and later on became a place to which she went when she wanted to escape Sydney. Our visit together was her first journey back since the trip that had inspired her book in 1995.

It was a revelation to be in a landscape that, superficially at least, offers so little with someone who knows it and loves it and wants to share it with you as much as Coral does Brewarrina. Her love is not blind however, and perhaps this is why her poetry is so powerful. She pulls no punches in her descriptions of and dislike for the culture, the way of thinking that has created this broken land, yet they are not the glib responses of someone who is a detached observer.

[Above] Coral Hull and bearded dragon, Brewarrina, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Amanda Shillabeer, 1999)

It is precisely because you can feel, in every word, her deep identification with this lovely yet ruined place that they resonate so strongly. And so it was a delight for Amanda and I to be with her when, after much searching, she finally found a leopard tree to show us its distinctive mottled bark; to sit on the banks of the river watching the pelicans floating on the water and some pre-teen boys - black and white together - show off for us on the weir; to pull over on a dirt road to get a closer look at the bearded dragon lying basking in the sun; and to walk around the abandoned property she lived at in her late teens listening to the wind in the distance soughing through the river red gums.

For our stay, we borrowed a car from a friend of Coral's father. This meant we were able to explore the area thoroughly, visiting places that had emotional and spiritual significance for Coral. The weather was quite mild, but the effects of long-term drought were to be seen all around. The land really was broken - parched and cracked - and the recordings I made of us walking amongst the grasses that tuft out of the red dirt sound like crackling tinder, so dry was the vegetation. Apart from the larger gums close to waterways and stands of scraggly mulga there's not much in the way of trees. A great deal of the land was cleared for grazing in the nineteenth century, and now saltbush predominates.

Driving through at high speed the landscape can become a blur, the red dirt and low scrub seeming to stretch forever into the distance, as far as the eye can see and a lot further again, with nothing to break the monotony. But when you take the trouble to truly observe your surroundings you become aware of all the brilliant and subtle variations that nature provides. I'd always been astounded on long road trips overseas when my fellow passengers spent most of the time asleep. If you don't watch and engage with the landscape during a six hour drive across the Namibian desert, for example, what point is there in being there? You may as well stay in your hotel in Windhoek, or, indeed, not leave home.

|

So driving around Bre Coral, Amanda and I were constantly on the alert, pointing out to each other and discussing everything we noticed - from flora and fauna, unusual land forms, plays of light upon the landscape, to the tell-tale traces of human attempts to control and exploit the environment.

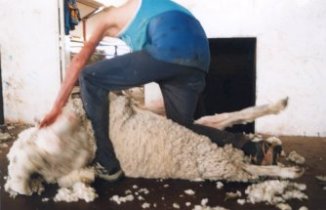

In the pub at Bre, the blokes at the bar told us there was shearing going on at a property outside town, and we should go and have a look. So the next afternoon we went. We watched, amazed, as the shearers in their harnesses cradled the sheep in an extraordinary embrace, clipping the dense fleeces in long strokes until they fell away from the animal. But with the wool stockpile and other factors, wool is not the profitable business it once was. Hence - the ten cent lamb.

As we wandered out to the pen where the newly-shorn sheep were being held, we noticed a trailer partially covered by a tarpaulin. Inside were three lambs covered in blood. Two were clearly dead but the third - and smallest, only a few hours old - was still alive. Just then, the property owner came out of the shed and, seeing where we were, came over to remonstrate. During the ensuing argument he maintained that the lamb, crushed after being separated from its mother in the holding pens, was unlikely to survive, and anyway, with lambs worth only ten cents a head, there was no incentive to help it, as no farmer had the time to hand-rear a lamb for such little return for his effort. |

[Above] Dead and injured lambs born 'out of profit season'. Dying Lamb, The Four Mile, Brewarrina, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Coral Hull, 1999)

But it's not just the sheep that are seen as dollar signs rather than living, sentient beings. Other species, both introduced and native, are subject to the same fate of being commodities in the service of humans.

To an animal ethicist such as Coral, feral animals can be a vexed issue. While they can - and often do - damage the environment and threaten the habitat of native species, they remain beings who are entitled to live their lives. But in Bre the feral pigs and goats are hunted by both professional hunters and suburban cowboys who travel up for shooting weekends. When Coral made the drive from Bre to Bourke in 1995, she expected to be compiling a photo-essay about an abandoned knackery, where during the '70s broken-down racers, unwanted pets, brumbies and other horses were turned into a quick profit on the European market. Instead, she found it fully functional, processing goat meat for export to game-meat markets worldwide. We also made the 90km drive, incidentally seeing along the way the only roos we saw during our trip - fresh road kill. I've no doubt both Coral and Amanda were as inwardly relieved as I was to discover the abattoir was not killing that day, but the guided tour we were given from the killing box to the refrigeration plant were still chilling.

[Above Left] Justine Lees interviewing a slaughterhouse worker with Coral Hull looking on at Sitebarn slaughterhouse, Bourke, New South Wales, Australia. (Photo by Amanda Shillabeer, 1999) [Above Right] Coral Hull stands at the metal crate that the decapitated heads of goats are thrown into from up inside the Sitebarn slaughterhouse, Bourke, New South Wales, Australia. (Photo by Amanda Shillabeer, 1999)

I kept recording throughout, as the manager walked us through the slaughtering process, describing each step in detail. I had to emotionally distance myself, as Coral had done when she first visited four years earlier, to be able to remain intellectually engaged. Interestingly, I found that the headphones I was wearing somehow helped me maintain some distance from the heart of the matter - that we were discussing the killing of animals - and enabled me to question the man in some detail. It was in fact the reverse of experiences I've had travelling overseas, when I've abandoned recording environments and people, and sometimes even stopped taking photographs, because the introduction of the device to a situation immediately creates a kind of detachment or separation that seems to limit interaction and interplay with the people and the places you have travelled to experience.

And so the impressions that stay with me now of the Bourke slaughterhouse are the cold air and the red painted floor of the processing room and the sounds - the manager's voice reverberating through the big empty spaces as he explains how a goat is eviscerated, a tap dripping somewhere onto a concrete floor, the buzz of the stunner and the constant dull roar of the refrigeration plant, a chain banging against a post in the breeze and, behind it all, off in the holding pens, the bleats of the goats and the calls of the ravens.

Newly shorn sheep standing in the holding yards. [Above Left] Sheep in Yards, The Four Mile, Brewarrina, New South Wales, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1999) Shearer getting intimate with sheep [Above Right] Shearer #2, The Four Mile, Brewarrina, New South Wales, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1999)

It's certainly an experience travelling to somewhere like Bre with a person who has the courage of their convictions. As Coral has said to me many times, if she comes across an animal in any kind of distress she will not rest until she has either saved it, or ensured it has been humanely put out of its misery. One of the consequences of this was a protracted and fairly tense stand-off over the ten-cent lamb: the lamb we found who had been left to die near the shearing sheds.

The property owner maintained the lamb had been badly injured and there was no point attempting to tend its wounds or hand rear it. We were angered, however, by the fact he had left it to die a protracted and painful death in the trailer. Both Coral and Amanda, who grew up on a sheep property, questioned the extent of its injuries, and asked we be allowed to take it - if it died, at least it had known some warmth and comfort in its final hours. He was initially adamant that we could not have it, but as the argument heated up and we repeated to him his assertion that the lamb was worthless to him, he finally capitulated. He'd had no option really. Coral had insisted we would not leave without it.

Several hours later, after we had managed to find a baby bottle in the Brewarrina News agency and coaxed the lamb to take his first mouthfuls of milk, we tracked down a local woman who often took in orphaned animals, both native and domestic.

|

Just as well really, as Coral had been ruminating upon ways to convince Hazelton Airlines to let us take the lamb back to Sydney with us. [And the good news is we proved the property owner wrong. The lamb did survive, and is still well and good].

On the other hand, the property manager who we dragged away from checking the fences to help us rescue a galah caught in wire on a pole was bemused by the three strangers intent on rescue. Coral had been driving our borrowed car along the Mitchell highway when we screeched to a halt in the middle of the road.

The galah had caught a claw in a twisted wire atop a four metre pole in the middle of nowhere. Dehydrated and distressed, it was unable to free itself. While Amanda and I sat and waited, Coral went in search of help. Surprisingly, in such an desolate landscape, she didn't take long. The man she brought back had thrown a ladder onto his roof rack, and with some wire snips the galah was soon flying off.

It would have been rewarding to do more to help the kangaroos, but the roo shooters we met that evening were not people to reason with. They sent shivers up our spines. As we looked at their ute with its huge spotlights, we thought of all the kangaroo bones we'd seen the day before in a pit behind the roo plant, and the soft pelts the plant manager had given us to stroke ... skins that had once been beautiful red kangaroos. |

[Above] Justine Lees, Coral Hull and the galah entangled in wire on pole, Bourke Road, Brewarrina, New South Wales, Australia. (Photo by Amanda Shillabeer, 1999)

Travelling and exploring new places is a sensory experience - sights, smells, tastes and textures all capture the attention and the imagination. For me, as the sound recorder, the auditory impressions of Bre were further heightened. Wearing headphones and using a high quality microphone, there is not a detail or nuance in the sound world of a location that you miss. Therefore it is disturbing that much of the time we were out of town I heard very little. Coral's poetry often takes the voice of her father describing the Brewarrina of his childhood, when birds, animals and fish were plentiful. But the only bird that I heard regularly was the raven: that ominous aark-aark-aark-aaaark that always seems so desolate. Environmental degradation through inappropriate farming practices has meant many native species have been displaced from their habitat. So apart from the emptiness of the breeze playing over the dusty red plains what we heard most were the sounds of white civilisation's intervention in the place - from the bleats of the sheep in the holding yards to the machinery roar of the kangaroo boning factory, the men in the pub complaining about the wool stockpile to the aborigines arguing drunkenly down by the weir.

[Above] [Above Left] Coral Hull and Amanada Shillabeer heading towards abandoned shack, Brewarrina, New South Wales, Australia. (Photo by Justine Lees, 1999) [Above Right] Justine Lees, Amanda Shillabeer and Coral Hull recording poetry, Brewarrina, New South Wales, Australia. (Photo by Cliff Hull, 1999)

Maybe as a response to this we found ourselves spending a lot of time in and around an abandoned drovers' hut about thirty kilometres out of town. We sat on the red dirt and discussed each poem as Amanda read them for my microphone, and took many photographs that showed the detail and texture of the building and its surroundings. We created music out of the reminders of past: an old gate swinging slowly on its rusted hinges, the whistling of the wind through the chimney and the shattered glass of a window, a branch scraping over the tin roof, hollow knocking on the old water tank.

|

We fossicked for old bottles and other remnants (the pair of rusty hand shears I found caused quite some consternation when my bag was X-rayed a few days later at Ansett check-in)! This place became our place.

Flying back after three days in Bre was an emotional experience. Amanda and I both felt like we had somehow become connected to this landscape - desolate, broken but majestic. We had arrived as three strangers in a place that was to two of us very foreign, but we left as friends who had shared a significant experience.

Although Coral is keen to emphasize that Broken Land, like all her work, is about the universal rather than just the uniquely local, I've no doubt that for Amanda and me being there in Brewarrina helped ground the universalities in very concrete and immediate reality, thus deepening our understanding of and feeling for them. It also reinforced to me the power of words to inform and affect.

Our world is in information overload. Didactic messages come at us from all quarters. But poetry is able to reach out and touch people on a more visceral level that I believe is ultimately more compelling than any number of earnest documentaries or long-winded dissertations by 'experts'. |

[Above] Coral Hull and Justine Lees at Twin Rivers, Brewarrina, New South Wales, Australia (Photo by Amanda Shillabeer, 1999)

I remember with fondness and gratitude the warmth, intelligence and generosity of Coral and Amanda, who showed me once again the joys of creative collaboration with like-minded people. Coral in person proved to have the qualities of her poetry - insight, an honesty and frankness that is at times brutal but never gratuitous, and a passionate advocacy for all living creatures. And Amanda impressed us both with her emotional and intellectual affinity to the poetry.

Now, nine months after that journey to the broken land of north-western New South Wales, I still have a little memorial to Brewarrina. Sitting on my hall table is a circle of five stones I picked up from the ground next to the leopard tree, which as I pass each wintry Melbourne day remind me of the red heart of this continent.

About the Writer Justine Lees

|

Justine Lees was born and raised in Melbourne. She received a Bachelor of Arts in Media Studies and Psychology from Swinburne Institute of Technology before working in the court system for a few years. She joined the ABC in 1989, and since 1992 has been a producer for the Radio Drama department, making plays, book readings and poetry features for broadcast on Radio National and ABC Classic FM. However, she remains adamant that if you'd told her before that then she would end up working with poetry AND enjoying it she would have laughed in derision. Like many of her contemporaries, she was deeply scarred in her formative years by rote learning of "I love a sunburnt country ... " Now, she greatly enjoys working with poets and actors in close collaboration, exploring texts and recreating the world of the poetry in sound. A program she made about poetry and schizophrenia featuring the work of the Loose Kangaroos, a group of poets living with the illness, won the 1999 Australian and New Zealand Mental Health Society Broadcast Media Achievement Award and was highly Commended in the 1999 Human Rights Media Awards. Justine is a keen traveller and has visited, amongst other places, South-East Asia, the USA, Mexico, Cuba, Botswana, and Namibia. She loves deserts, and since her trip to outback NSW with Coral Hull is determined to explore more of Australia. |

[Above] Photo of Justine Lees by photographer unknown, 1999.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.2 (September, 2000) |