MEMORY/ HISTORY/ ROME

By Andrew Taylor

[Above] Saint Peter's and the Tibur. (Photo by Andrew Taylor, 2004)

Back in Rome again!

Well, I was sitting beside the Gesu, traffic on Corso Vittoria roaring past me, with one hand in the fountain, my suitcase beside me, and grateful to get out of England. That land where in 1963 Australians were still considered colonials, where if you reached for a disused newspaper on the pub bar some clawing old geezer would claim it as his own and accuse you of theft, where women north of London seemed never to have washed their hair.

Where the Beatles were raging, where every second pair of knickers or carrybag was printed with Her Maj's Union Jack, where I was led to believe lovely women my age stripped off in Carnaby Street shops because there were no changing cubicles, so they could try on the next best thing! I met a lovely woman in London, but wasn't smart enough to keep her. I believed her lies about her commitments and I think she believed mine - though mine weren't lies. Well, most of them weren't. We did improvisations of Beckett in empty rubbish bins at midnight - amazing how early London went to sleep as the Tube stopped at midnight. And months later, when I was married in Rome, she drove across with my Australian friends to be there too. A true friend, whom I've not seen since.

So there I was, dipping my hand into the fountain outside the Gesu, in the afternoon shadow, listening to its mournful rhythmic splashing, thinking for a moment Rome was cold. Picked up my suitcase again - in those days cases didn't have wheels - and lugged it a few more blocks, sweat pouring. It was, after all, only September. To the Albergo del Sole.

* * * *

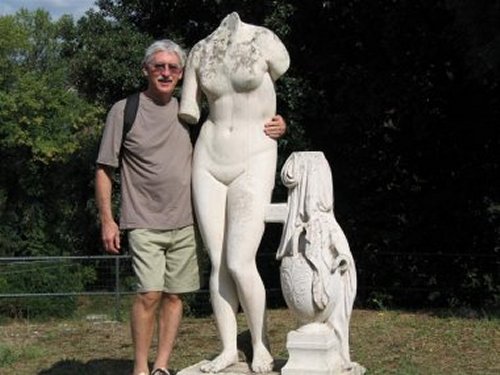

[Above] Andrew and faceless friend at Villa Adriano. (Photo by Beate Josephi, 2004)

The Albergo del Sole claims to be the oldest hotel in Rome and it was certainly antiquated then. But friendly, as it probably still is.

I took Cosimo, a python, out of his pillowcase and let him free-range around the bedroom, which was sunny, almost a miracle in cheap Italian hotels. He warmed up and got speedy, so I played with him for a while before unpacking and thinking what to do next. I'd stayed at the Albergo before, and knew Campo de'Fiori had lots of budget eateries nearby, but what could I get for Cosimo to eat? Ted had told me in London that he probably wouldn't need another meal for a week or so, so I put him in a box, put the box in the wardrobe, went out and ate.

* * * *

The British Institute in Rome had offered me a job as a teacher of English, probably on the basis of my having a good degree in English Literature. In fact, on graduating from Melbourne University I'd been offered the opportunity to study at the feet of Dr Leavis of Downing College, Cambridge, as most of my teachers had, but declined.

|

It was another thirty years before I finally dined at Downing, now a Professor myself - while Leavis, for complicated reasons, was never made a professor at Cambridge, and was long dead before I entered the college. So here I was, after a year in Florence, and with the required Diploma for Teaching English as a Foreign Language acquired in London just a month earlier, knocking on the gates of Rome.

Cosimo was a problem. Somewhere, sometime, I had to find him dinner. I also had to find somewhere to live, since I was going to be in Rome for all the foreseeable future, maybe three or even five years, at least until I was near death. In those days we all lived forever, but forever ended some time around thirty. And in January the girl in Melbourne I'd loved for four years and agreed to marry would join me. I had serious business to attend to and, since I'd been in Rome a couple of times before and was not here to gawp at the sights, I attended to it. |

[Above] Bramante's 'Tempietto' (Photo by Andrew Taylor, 2004)

The meeting with Mr Goldie, Director (and owner, I later learned) of the British Institute, went okay. I'd been interviewed by him when I'd applied for the job, had dutifully gone to London to get my Diploma, and was now reporting back. He was thin like some Highland breed of dog, tightly parcelled in a tweed suit and waistcoat, even in Rome's summer, and reassuring. I joined the staff of the British Institute, which is still to be found in Via Quattro Fontane, and taught English.

I learned more about the English language in those nine months than I knew was available to learn. Defining and non-defining relative pronouns (or were they participles?), when to say whom rather than that, pardon rather than just gawp, and how to wear a tie of the right colour on the day of Churchill's funeral.

Mrs Goldie who, so far as I could discern, did nothing whatever, complained endlessly about Italians and the useless maids she had to deal with. I learned that the English they spoke was not mine.

|

It had gradations of class I, as an Australian, had thought belonged only in novels.

I tried to teach my students a different English, as did many of my colleagues, but I was there for too short a time.

Mr Goldie was a kind and understanding Director, actually owner, of the British Institute. He took my resignation with resignation, probably having to deal with two or three such things each year. He probably thought my reason for leaving was a fake - that I'd been offered a job at Melbourne University. But it was true. |

[Above] On the bus: the last of the Spanish hippies. (Photo by Andrew Taylor, 2004)

While there I met my cousin or, more accurately, a second or even a third cousin. My brother and sister knew Russell, but I'd not met him before the new teachers gathered before Mr Goldie for our induction. He was ten years older than I, lean like Goldie, his head slightly inclined to the right (perhaps a sight defect?) and slow but precise of speech. He had done what I'd not done, gone to Cambridge, though it might have been Oxford, and now we were listening to Mr Goldie together, who probably hadn't. We taught together that year, but were never close. I visited him probably fifteen or eighteen years later, in his apartment in Rome, north of the Vatican and was no closer. In his well decorated but rather shadowy apartment he didn't relax - I had not known him really as the relaxing type - and seemed both embarrassed and determined not to let his glass of whatever we were drinking out of his hand

Three months ago I read his obituary: alone, alcoholic, gay (the obituary didn't mention this), dying slowly and unattended of multiple cancer in rural Victoria where he'd been born. He couldn't have got further from Rome!

* * * *

|

Cosimo embarrassed me by escaping from his box - Ballantynes Scotch, I still drank Scotch then - one sunny afternoon and heading who knows where. The guy who cleaned the rooms in the Albergo del Sole was too terrified to say anything, too terrified by Cosimo I imagine. I found him under the bed, wound him around my arm, played with him, and offered him a better home.

Cosimo wouldn't accept it. I found food for him at the Porta Portese market but he refused to eat it. Ted, who had sold him to me, warned of this: sometimes pythons get neurotic and won't eat. Cosimo wouldn't eat, no matter how I tempted him, and he died a week later. By that time I had found a place to live, on the outskirts of Rome, a long and up-and-downhill bus ride that took most of an hour from the British Institute. (It is now easily accessible by Metro, but rather shabby.) Colleagues at the Institute lived in corners of old Palazzi or somewhere in Parioli, certainly at better addresses than mine. But my apartment was new, almost unfinished, clean, with a view across a very large and tree-filled schoolground, and quiet. Cosimo was put to rest there, in the schoolground's long grass. |

[Above] Storm over the Gianicolo. (Photo by Andrew Taylor, 2004)

* * * *

Jill joined me shortly after the New Year and we were married on the Campidoglio. Looking back at it, my colleagues at the Institute must have thought us sweet and naïve. I taught, while she, I'm ashamed to say, had very little to do. Rome offered her almost nothing in terms of meaningful work. I hope her enforced idleness during those months was compensated by her ability to see Rome. We would meet during my lunchtimes, when everything in the city shut down until 3.30 or 4 pm, depending on whether it was on summer or winter time, and picnic somewhere. Usually it was behind the Campidoglio, in a leafy bit of terracing nobody else seemed to know about, looking down onto the Forum. Or it could be Piazza Navona, or near Stazione Termini, closer to the Institute. Even in winter we would rug up and picnic. The Institute didn't pay enough to lunch in restaurants.

In fact the Institute didn't pay much at all. Though it wasn't stingy, in line with other language schools what it paid was not much above subsistence for two young people who had, or at least who wanted, the world at their feet. We managed seats at the opera, but restaurants were another matter. We felt a bit like the urchins in the street, noses to the windows, watching those inside having a good time. But this wasn't entirely true. While much of what Rome had to offer was far outside our financial reach, it offered so much that cost nothing.

[Above] The Campidoglio seen from the Forum. (Photo by Andrew Taylor, 2004)

So when I got a letter asking if I would be interested in applying for a job at Melbourne University, it took us some time to deliberate before writing back. When, some time later, I formally received the offer of a job, it took almost a week of deliberation and discussion before I accepted. Italy was where we had left Australia to live, and Russell, my cousin, had been there for years. I had been in Italy only two years, and only one of those had been in Rome. (The first had been in Florence.) Shouldn't we stay longer?

We sailed from Genoa in late August 1965 on the SS. Galilio Galilei, a new boat at that time. The Indian Ocean was monsoonal and wildly rough. When we celebrated Jill's birthday by ordering two bottles of champagne for our table, there were only eight people in the whole dining room, and we were the only two at our table. I don't know if that rough passage was telling us something, but it might have been an omen that the road ahead would not be smooth.

* * * *

I wrote the preceding passage in Rome, in December 2004. It was an exercise in memory, an attempt to see whether the past is alive for me. It is.

I'd been in Rome since early August 2004, and would return to Australia, where I am now, at the end of January 2005. I was the recipient of a Residency at the BR Whiting Library, a small but bright apartment high above the viale di Trastevere, with a large terrace looking west towards the sunsets over the Gianicolo. It had been forty years since I'd spent so much time in Rome, though I'd revisited it now and then as a tourist.

I was there as a beneficiary of the Literature Board of the Australia Council, and also due to the generosity of expatriate artist Lorri Whiting who, more than a decade earlier, had given the Board her apartment and its collection of books in memory of her poet husband, Bertie Whiting. In my application to the Board, I proposed to write a long poem, a poem which not only explored memories of my earlier time in Rome, but which explored memory itself. And that's what I did.

[Above] Ancient stones, modern Romans. (Photo by Andrew Taylor, 2004)

By December I had written a poem in three parts, eighty pages long. It needed some revision and much polishing, which it has since received. It's now roaming through the cruel world, seeking a publisher. I have recently privately printed a very small number of copies to give to my close family and to friends.

* * * *

The reasons I gave the Literature Board for applying for the residency in Rome were multiple and interlinking. During my first time in Italy, while living in Florence, I had a very brief but somewhat seismic relationship with an American girl. The fault lines this produced in me weakened my subsequent marriage to Jill and contributed to its failure. (Roberta and I had spent a week together in Rome, and she left for the USA the day after our return to Florence. Many years later she died in a plane crash in Africa.)

Also, in 2003 I was diagnosed with colorectal cancer which, it was discovered during surgery, had spread to my liver. I was given a one in ten chance of survival. After further surgery and six months of chemotherapy, my survival chances were ranked about two in ten. Far from filling me with fear and depression, this experience reinvigorated my delight in all around me, and my love of life.

It also made me acutely aware of how precious was my past, and the role that memory plays in constituting our consciousness and our personality. Rome, for me, was history personified. Or, more accurately, history in travertine - strata upon strata of it, rather like the mind itself. It contained not only its own past, but also a key part of mine, and I wanted to go back, search it out, find out what it still meant - because it was still the site of Freudian 'unfinished business' which needed to be confronted. But the poetry would not be a Freudian 'talking cure'. I don't believe in poetry as therapy. Rather, I would embark on a 'walking cure', and the poetry would be my companion. My long poem would be, if you like, the map of my incessant walking though Rome and memory.

And that's how it turned out. One of the main characters in the poem is the city itself, so much so, in fact, that it almost completely dominates the poem's conclusion (the person being addressed throughout the poem is my wife, who joined me in Rome after attending a conference in Brazil):

|

Rome is full of past

its gaps ruins passageways

a lure for map-wielding Swedes

flop-hatted Japanese

and everyone in between

including

beggars and their dogs

gypsies camping anywhere it seems

belonging nowhere

ubiquitous Africans

peddling off-the-truck

trinkets and handbags

but

that woman with her bulging shopping

the frail old man guarding his dignity

with a tie and suit

the girl whispering to her mobile on the crowded tram

the old woman walking while her daughter supports her

the schoolkids with their oversized backpacks

the man reading L'Espresso at the bus stop

the cashier plomping a chiuso sign in front of my shopping

the girl on her scooter waiting at the lights

and people watching her she is so beautiful |

[Above] Tourist nuns at S. Paolo fuori le Mura. (Photo by Andrew Taylor, 2004)

|

the riot police in Piazza Venezia with their plastic shields

the couples strolling Campo de' Fiori

or sipping wine at little tables

in the warm twilight

this is their city

what do they care

what one man found here

forty years back

and what he did with it?

I'll sit for an hour at the Taverna del Campo

with a glass of torgiano and a cup of unshelled peanuts

as much at home here as I will be anywhere

watching the 116 lurch over the cobbles

wince at the fat little busker's voice

(though I'll give him a coin for trying)

observe how the floodlit flower stalls brighten

as dusk thickens and streetlights waken

the ochre richness of the ancient walls

back in our apartment

I'll clear the papers and laptop from the table

sweep out the dust of your absence

chill a bottle of your favourite prosecco |

[Above] Piazzo del Popolo seen from the Pincio. (Photo by Andrew Taylor, 2004)

put clean sheets on the bed

ready for your return

tomorrow

while as for our anniversary -

but I celebrate that every day

By the time I'd written that, I'd discovered that the ghosts of the past had died. Roberta no longer haunted the lonely tunnels and empty spaces of the Palatine, which we'd explored hand in hand - conscious that within three days we'd be separated by her return to the USA. (In fact, the tunnels are today off limits to tourists, their entrances barred by steel grilles.)

[Above] Stazione Termini, the greatest railway station in the world. (Photo by Andrew Taylor, 2004)

The ghosts have vanished

the guilt or nostalgia that fed them

gone - gone through and gone

They still whispered when I arrived

and you from Brazil

but they gave up and quit

when we set out to conquer Rome together

not exactly barbarians

but to make it ours

which we have

in our work

in our walking

in our lovemaking

in our being here together

They haven't gone whimpering

under the Palatine or Forum

where they slunk before

nor to the dismal underworld and miserable shores

where Aeneas encountered them

nor do they hover at the edge of dreams

like hesitant guests at a wedding

they have simply gone

like an old shirt

their threads disengaging

disentangling

floating away into nothing

Now you too have gone

but you're a tangible absence

the promise of your return in two weeks

an anniversary

|

It was more than the passage of time that had laid Roberta's ghost to rest. My first marriage might have been fractured by memories of what happened forty years ago, but not my second. The poem ends, as I quoted it earlier, by addressing my second wife - partner now for thirty years. The whole poem, I came to realise, was a love poem addressed to her. And to Rome.

This was not something I'd foreseen. And it's not something that could have happened had I not been able to spend so much time in Rome, walking and walking through it, its heat, its slushy autumn, its winter with the snow on the mountains visible to the east from our apartment. Rome became such a character in its own right, with its own history and memory - part destroyed, part visible, part needing or suffering reconstruction - became my third partner in writing the poem.

The poetry itself was one; my wife - when she was with me, and perhaps even more when she wasn't - was the second. |

[Above] Ghosts in the Campo Marzio. (Photo by Andrew Taylor, 2004)

Our history has been one of intermittent separations, as she maintains contact with her family and friends, and also professional contacts in Germany, where she comes from. My Collected Poems has a number of poems about the way our frequent separations nurture our love: it may in fact be true that absence makes the heart grow fonder - so long as one bears in mind that one of the older meanings of the word 'fond' is 'foolish'. Perhaps one manifestation of foolishness is the writing of poems. Here are four small sections of my long poem addressed to her:

What gift can I make to you

who gives me so much?

* * * *

Gift

in German

your language

means poison

giftig

yes

last year

was a poisoned year

how easily it might have been

my our

last

what can I give you

to heal such

fear such

distress

I scored then

across your face?

* * * *

something akin

maybe to that poison fed

six months into my blood

bringing me health again?

[Above] The easy life but not La Dolce Vita. (Photo by Andrew Taylor, 2004)

* * * *

I'll give you if I can

another year together

and hope

and memories

not just of pain but laced

with lives as lovely

as the gold

flash of a fish

twisting or a wave

breaking

and maybe a poem -

this one with its clumsy

meandering towards your return

with all my trash and treasures on display

cheap but at least

not something bought in a shop

no matter what it cost

us both

* * * *

Quite deliberately, I refused to use Rome as a base for a wider exploration of Italy and Europe. I have been to Europe many times, for both family and professional reasons, and I wanted this visit to be the antithesis of a tourist trip. True, I explored countless fascinating historical sites within the city and its outskirts, but it was today's Rome that I immersed myself in. Today's Rome was what I walked through, and today's Romans were those I talked with, walked amongst. I bought my food from them, had my hair cut by them, discussed my translations of Montale with them. They helped me get connected to the internet, sold me bread, capsicum and fiori di zucchini at the local market, invited me, my wife, and my daughter, to share Christmas with them. They were kind, helpful and, above all, courteous.

Rome is not only a modern city, it's also a major political centre in the EU. HV Morton deplored that it was made the newly formed Republic of Italy's capital in 1870, rather than Milan. If he could see it today he'd change his mind. The noisy, grubby, brawling city he wrote about when I first lived there has been transformed into a sophisticated but still earthy city where good and affordable food is no more than a block's walk away, where schoolkids scramble onto the trams and buses as school ends at 2 pm and haul out their mobile phones, where an elderly woman vacates her seat on the tram for a young woman with a child. Rome is a modern city like any other - with one difference.

[Above] At our favourite taverna in Campo de' Fiori. (Photo by photographer unknown, 2004)

It's impossible to walk a street in Rome, even on what were once the outskirts where forty years ago I had my apartment, without being aware that one's walking on three thousand years of history. This is instinct in the Romans themselves, who wear their history as stylishly yet also as unselfconsciously as they wear their clothes. And living for six months in Rome I came to feel that to some extent I shared that sense of history, not as something external, learned, but internally, absorbed almost unconsciously. I can't claim that I became a Roman, in the way that having lived for more than a decade now in Perth I can claim to be, in some senses, a Western Australian. That would be too presumptuous. But Rome gave me a sense, not only of its own history, but also of mine. Painful experiences, and happy ones too, from my past came to be integrated with my present life in a way I had never thought possible before.

In my poem Rome and the human mind become images of each other, with their layers of past, their interacting layers of memories, both conscious and unconscious, which not only underlie the present but even, in a very immediate way, help to constitute it. Writing my poem, I was not bringing the past back to life, but discovering how it had never died. Realising this, I simultaneously discovered that I was now not possessed by my past, haunted by it, but, on the contrary, I was possessed of it. I had come into it, as into an inheritance. I feel that I have been given myself.

* * * *

Two major operations and six months of chemotherapy make you wonder about your durability. I had the most expert and supportive medical attention, of a quality it would be hard to find anywhere else in the world. Still, my body was giving me a very clear warning. My use-by date is coming up, and though it may be postponed, one day it will inevitably arrive.

This isn't a very original thought. Much of literature is about dying, or imagines forward to dying. But for me that was always someone else's dying, a surrogate or stage version of it, until 2003.

|

Then I realised it was my own that I had to consider.

So I would be the last person to deny the reality of death, after what I've experienced. But I believe that there is a kind of living on after death, and Rome showed me how to imagine this. The individual dies, obviously, but like the butterfly in Patagonia, whose wing beats are involved in a cyclone in Florida decades later, its future continues.

Rome is a city whose past inhabits its present as much as its present inhabits its past. The modern street plan in places follows ancient building lines laid down more than two thousand years ago. The tram I often took passed the Colloseum, which I would rarely glance at as I read the paper. Every time I walked over the bridge from Trastevere, where I was living, I could see Saint Peter's in the distance, if I chose to look. History was everywhere, but alive today, in the ordinariness of our daily life. History is part of our living. We too, after our death, become part of the living of those who come after us. |

[Above] The largest marble typewriter in the world: the Victor Emmanuel Monument. (Photo by Andrew Taylor, 2004)

What Rome taught me, therefore, is that the past doesn't actually die. For some visitors to Rome, for example tourists, the past is a display, a son e lumière put on for their entertainment. But for people who live there, who live within Rome, the interleaving of past and present is the fabric of their city, and the fabric of their lives. The past, if you like, is the city's unconscious:

Rome was six metres lower

in Classical times

the guide explained

but where does the extra

altitude come from?

from demolition rubble I suppose

and dust and a few solid metres

of accumulated time

and history

and the rubbish of failure

If cities grow higher do I as well?

Am I taller now than forty years ago

strata of wisdom happiness regret

augmenting my stature?

Appealing maybe

maybe untrue.

A life is built of its past

and memory lives in the present

while change is the act of becoming

not more of, but more like ourselves -

our hidden spaces and ruins

palaces gardens and tombs.

Treat them with tact since they hold

not just the shape of the past

but the whole bright structure erect

[Above] Sunset over the Gianicolo (Photo by Andrew Taylor, 2004)

There is nothing unique about Rome in this respect: every city, every place that has been lived in, is this amalgam of past and present reaching into the future. And so is every life. But Rome helped me not only to understand this, and to articulate it so that I could understand it, but also to know what it means to live that understanding:

Beneath San Clemente

an ancient Church

beneath the Church

an ancient house

beneath the house

an altar to Mithras

and beneath the Mithraeum

a spring of fresh water

filling the centuries

with its living voice

About the Writer Andrew Taylor

|

Andrew Taylor was born in Warnambool, Victoria, and is a graduate of Melbourne University, from which he holds a Doctor of Letters. He is the author of twelve books of poetry, a critical study of Australian poetry, the libretti of two operas (with the composer Ralph Middenway), and co-translator with Beate Josephi of an anthology of poetry by four German and Austrian women poets. He has also compiled several anthologies, and written numerous academic articles. He was regional winner of the Commonwealth Poetry Prize in 1986, and of the Western Australian Premier's Prize for poetry in 1995, and is a Member of the Order of Australia. He has given readings in the UK, USA, Canada, Germany, Austria, Italy, Denmark, Switzerland, Spain, 'Yugoslavia', India and Singapore, and has had poems published in Germany, the USA, Canada, Great Britain, Denmark, Sweden, Ireland, Switzerland and India. He has lived and taught at universities in Melbourne, Adelaide (where he chaired Writers' Week at the Adelaide Festival, and was one of the founders of the Friendly Street Poetry Readings and Australia's first Writers' Centre), Germany and Perth, where, until recently, he was Professor of English at Edith Cowan University in Perth, Western Australia. |

[Above] Photo of Andrew Taylor by Beate Josephi, 2004.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.11 (June, 2006) |