THE RETIRED HERMIT

By Peter Davis

[Above] Mt. Bogong 1, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

'Since I have yearned after the hidden heart/ I am become the wanderer among the stars of this revelation:

And the term of my journeying afar/ Is as that of the viewless winds.'

(from the 1902 Australian poem 'The Wanderer' by Christopher Brennan)

I became a hermit gradually in 1987 on a mountain near the small town of Harrietville in north-eastern Victoria. This was soon after my HIV diagnosis, when I was 19. Disclosure of my HIV status to people had resulted in impassive rejection, rather than curiosity or empathy and, subsequently, I needed to be alone.

The sensible thing to do - I thought back then - was to drop out of university. I sold most of my possessions and then started travelling on my own in an old car with a vague idea of going fruit picking. The car blew a head gasket while on a steep road, about one third of the way toward the peak of Mt.Hotham. For the next two days, I slept on the back seat wondering what to do, as I had little money till the next pension cheque came and no roadside insurance.

On the third day, while exploring deeper into the surrounding forest, I found a ruined hut. There are lots of smaller paths that you can never find on a map, which lead to remote places. I started to wonder about a particular track's history, while enjoying somebody else' choice of rocks for a campfire. The prospect of learning to live outdoors seemed more attractive than returning to Melbourne, where I could have ended up in a boarding house. For almost two years, I lived as a solitary in the ruin of that tiny prospector's hut, which I made waterproof with layers of tarpaulin.

|

Initially, I felt afraid of nature in the forest. A tiger snake might rear its head suddenly as a form of warning. The eucalyptus trees seemed to move at night in the strong winds as if they were miming. Even the noise of possums mating in trees had initially frightened me.

I was just unfamiliar with an environment that was not enclosed by walls. In the first months, I would get up once every night and place more wood on the fire, just to keep it smouldering. Often it would be hard to return to the hut and get back to sleep, because I had loitered too long outside, while mesmerised by the number of stars.

Sometimes, I would have HIV-related nightsweats that would dampen my sleeping bag in the swag. So I would make a bigger fire and drink a pannikin full of hot cocoa. Then I would get back into bed with my coat on. My mother provided a home for me during each winter. I stayed there for as long as she and I could tolerate each other. I did not pursue counselling after testing HIV positive and my subconscious anger then harmed many relationships. |

[Above] Mt. Bogong 2, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

The return to city life seemed to speed up my thoughts. I then started to randomly tell a few people that I was HIV positive. My disclosure to them seemed partly an intense act of rebellion. I said this news as if I were defying them to reject me; I became very strange back then, even to myself.

Both years, I returned to the forest after winter in poor health. It took on each occasion about a month for my general fear level to diminish. I also had difficulty with insomnia after returning. My legs were very fidgety at nights, as my body began to detoxify from the substances consumed back in the city. After about two months, I would almost stop feeling lonely and start to enjoy aloneness again.

I considered myself as being a bit like a squatter. The hills and mountains by the Ovens River have a rich tradition of miners and cattle finders, who often lived as solitaries. I never considered that I was actually more like a hermit because I lived without an occupation.

I probably was unaware about how rarely I spoke with people. Usually, if someone approached and asked me a question then I would try to answer. I seldom attempted to start a conversation. And talking to the creatures such as a bird, a wallaby or a wombat only made them more likely to flee.

I did a lot of meditation inside the forest and learnt to keep warm by lining my swag. A small tent worked best for the dry weather, when the forest was swarming with mosquitoes, gnats, sandflies and other insects.

[Above] Mt. Bogong 3, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

My favourite times were in the evening by a campfire, while reading with two candles. There is a certainly a peace inside solitude, particularly when you are camping near the sound of moving water. One morning, a snake came to where I was meditating with semi-closed eyes in the gentle sun. I jumped and shouted before the snake left me. It was like music listening to the birds at dawn singing their liturgy. I also looked forward to hearing the familiar scurrying of a wombat past the hut at the same time each night.

It soon became possible to save more than half of my Disability Support Pension each fortnight. I would hitchhike the forty kilometres from Harrietville to Bright, visit a bank and buy enough supplies to half fill a backpack. Also the small shop in Harrietville had a few healthy items.

It is possible for short periods to live mainly on a mixture of raw oats and soy milk powder. I often consumed a lot of nuts, raw carrots and vitamin supplements. I prepared meals, which were always a great feast made from dry goods and spices. My favourite vegetarian dish was lentil, sweet spice, dried apricot and prune stew. I used one stainless-steel billy for every meal, which had a small fitted bowl for warming up food beneath its lid. A wooden spoon and a steel-scourer were the other most useful utensils. Someone I met had said that a useful possession for living in a forest is one of those netting bags that you buy oranges in. You can place some food items in the netting bag and then place it inside a stream, which will make a reasonable fridge.

[Above] Mt. Bogong 4, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

Occasionally, people who provided a lift would ask what it was exactly that I did in the forest. They began by asking if I owned the land that I resided on. Often they wanted to know if I was currently employed.

They seemed to be questioning what I was contributing to society. I could have answered that I guess I wasn't consuming much. Thoughts - that was all I had to contribute to society - beautiful thoughts that come from peace; that was enough.

'They ask me why I live in the green mountains. I smile and don't reply. My heart is at ease.'

(from the early Chinese poet, Li Po)

Many local types of council have tried to remove people from forests, where they have resided unofficially. Perhaps this stems from a conventionality, where people perhaps feel more secure if everybody lives in a similar way. Hermits and squatters are shifted into emergency or government housing, where they grow to be less visible characters.

My sense of a routine in the forest became dependent on the position of the sun, or the brightness of the moon. Hours could pass just peeling bark from rotten twigs and finding dry leaves for the evening fire. I think that the prettiest orange seen by humans was through the trees at sunset. That was the time when I would start a campfire with old newspapers, usually choosing to burn first a news section. On cold nights in autumn, a blue tongue lizard might enter the hut and sleep close by for a bit of warmth. Sometimes in summer snakes came curiously near, when I meditated outside in the morning sun.

[Above] Mt. Bogong 5, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

When fit, I tried to walk once a week to the peak of Mt. Feathertop and make an overnight camp near there. From that alpine peak it is possible to watch the sunset across the valley over Mt. Buffalo. On overcast days I stared up and into the inner workings of clouds. The ritual of attaining this view became like my city-living equivalent of going to a cinema.

I liked to have short walks every day. There were many good guidebooks about the area. Whenever I went into Bright, I collected guidebooks on just about any topic, including a few on how to navigate the soul.

It is probably necessary for any hermit to follow some pathway of spiritual guidance. Or else solitude can become much like the adage that 'we are drowning in the water that the mystics swim in'.

A friend, who also once lived as a solitary inside a forest, said the following to me, when describing his experiences, "Looking back, I think I was fairly thin and bedraggled, and maybe looked a bit of a mess. But I wouldn't have seen myself that way. I was just living my life, and if I was quiet, then in other people's eyes I was quiet; but I wouldn't realise that myself."

|

There were a few other people who were also living reclusively on the same mountain range, near the Ovens River. They were recognisable from a distance, as they always wore the same clothing. I followed after them sometimes, hoping to meet. But they would mostly disappear after one or two bends in a foot track.

I once met another hermit at riverside, near a large and fallen tree. He was drinking from a cupped hand, while also slowly loosening his neck. We were both alone. I recall (from my diary) suddenly feeling anxious, as if being alone for so long had lessened my ability for communication.

I stood and stared at him: his still and soft eyes. He looked back with detachment, as if we were perhaps in a town and I was just another passer-by. His hair was grey and matted. He wore an old skivvy and a pair of loose shorts, which seemed to be inadequate clothing for early winter.

I looked at his bare feet and then back toward his green eyes. Then his stare fell abruptly like ripe fruit to the ground. Soon we passed on the narrow foot track without speaking. |

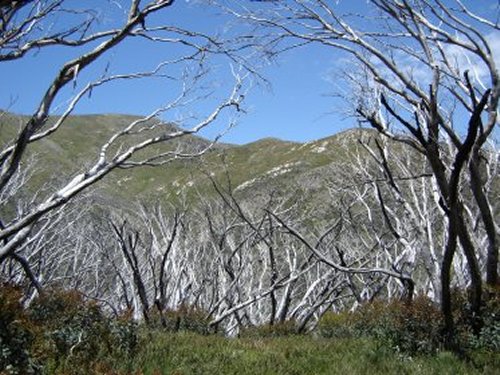

[Above] Mt. Bogong 6, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

It was not long after meeting this other hermit that I returned again to Melbourne. My mother had written to me about a group of HIV positive people, who were treating themselves with a regime of complementary therapies. We held regular group meditations and meals together. It was due to those people and also the continuing support of my mother that I was able settle into a social life again.

***

Recently, I decided to revisit my former dwelling near Harrietville and see if it was the same as I had remembered it. My life had become busy through employment and also having a family, so I could only manage eight days for this solitary sojourn.

It was much harder than I had expected to find the place of my old dwelling. I had to often leave crossed sticks on the ground to find my way back.

That first night, as I slept inside the hut, I dreamt that the older hermit and I met again. Within my dream, he whispered as he moved closer toward me. He said, "This forest is a church and the wind is my preacher." It then became apparent during my dream that the old man was actually myself. He represented the hermit that I would have become had I continued living for much longer alone.

The hut's ruin no longer existed. It had probably been destroyed by a bushfire. Only the small cluster of rocks of the campfire were distinguishable amidst some rye grass. I could not recollect any non-native grass around this particular area of the forest in 1987. It was likely that I had carried the rye seeds there, within the mud on my walking boots.

[Above] Mt. Bogong 7, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

Over the next five days, I hiked around the alpine range and fell frequently through time into recollections, such as: the constant slithering sound on the forest floor of shedding bark from mountain ash trees; the lyrebird's voice in the early morning mimicking all the birds. I wandered through an area of nature that earlier in my life had fostered my will to live.

I noticed that the creek was dry, which was not unusual for late summer. Yet there were many native shrubs growing within its bed. This indicated perhaps that no water had flowed along there for some years. I felt like I had fallen in love again with that forest, which had helped me to learn self-preservation within its shifting forces of nature. Some days, I felt like I had already died and fallen in love with everything.

I rediscovered some favourite foot-tracks, which were still not defined upon any official maps. Some of these tracks led me back to remote places within my memory. There were tracks that ended at open and sunny spots in the forest, where I could rest in the lively company of tall trees, upon a shoulder of the mountain. I felt content just to wander and breathe again the healthy forest dust, far away from rooms and industry.

|

To be where the equivalent of a phone ringing was the suddenness of a crashing branch. It seemed a pleasure almost to utterly tire my muscles. I hiked every day until dusk, in the hope that my mind may yet achieve some emptiness of thoughts like when an infant. I took frequent rests and dreaming.

Each day, I did not rise from where I had slept upon bark and stones, till my mouth had drooled fully. And then the first bird to sing before dawn was the bravest: barely able to see, slowly rotating its neck. Later each day, I hoped that my soul might waken at the sight of an eagle on a precipice.

I wore my old compass again around my neck - it was still working! I did not worry about the cuts, bruises and insect stings - nor the heat and the constant shortage of fresh water.

I slowly learnt again to ignore the pain from a backpack, which was a necessary weight to carry if I wanted to reach a place away from people. Those few nights alone again, deep in the forest, gave me an inner peace, which lasted for months after returning to the city.

|

[Above] Mt. Bogong 8, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

Historical example: Saint Antony is the most famous of the earliest known hermits. Born a son of rich parents, he became one of the desert fathers, who were austere Christian hermits. They lived in hill-caves that were distant to the Nile. These hermits attempted to relinquish all their sensual cravings. Their conviction was that solitude meant standing at the crossroad of faith in God and suffering humanity. Saint Antony moved even further into the desert and lived in an abandoned fort. Each year carriers brought supplies to Antony with the strict instruction to not disturb him. They would then hear terrible screams and groans of ecstasy from behind the bolted doors. After 20 years of this ritual, the supply carriers broke open the doors of the fort. They expected to find an emaciated madman. Antony emerged instead in perfect fitness and immediately began his life as a legendary apostle.

SECTION 2: Examples of hermits living around the alpine mountain ranges of Victoria

In February 2003, I caught a V-Line bus to the town of Bright, from where I planned to hitchhike on the Ovens Valley Highway to Harrietville. My plan was also to first stay two nights in Bright and try to meet locals, who might have interesting stories to tell about hermits. It is enjoyable as a freelance journalist to walk around a small town and ask to meet the local historians.

The V-Line bus stopped beside the large red hotel in the centre of Bright. It was 42 degrees outside. A strong northerly wind contained the heat of drought farm plains and southern deserts. To enter the pub immediately became a necessity.

The public bar was fairly quiet except for the sound of pool balls and bartenders occasionally loading racks of glasses. It was Saturday afternoon and a group of middle-aged people sat around the bar upon stools. I approached some of them and introduced myself as a freelance journalist, who was looking for any stories about hermits.

[Above] Mt. Bogong 9, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

I was directed to a man named Jamie, who 'might know a story or two'. Jamie had a thin face and definitive gaze. People began to snigger as I repeated to Jamie my query regarding any local hermits.

Jamie's reply was, "Okay, so which particular hermit are you chasing at the moment, mate?"

Jamie then turned to his drinking friend. "Do you remember Bones? Used to live up at Wandy [Wandillagong] there? Remember when the floods were on in '93, and Bones had his caravan tucked up in the bush somewhere?"

A man nearby answered, "Oh yeah, yep. And he woke up and he was floating down the creek! In the caravan."

There were a lot more stories about eccentric characters like Bones. I left the hotel half-drunk and wondering what actually constituted a real hermit. The people in Jamie's stories did live in isolated positions in the forest. They were often also regulars at a pub.

Historical example:

In 18th century England, a wealthy landowner was required to possess both a hermitage and a living hermit to impress the visiting guests. A grotto would be built for this purpose. The hired hermit would usually sit at the grotto entrance, while perhaps contemplating a skull or muttering eccentrically. It was not then uncommon for advertisements to be placed in local papers, which sought the services of an experienced hermit. The employment conditions were strict, and there was a recorded case of one hermit being fired for making nightly visits to the local inn.

On the first night of my two-night stay in Bright, I met a couple named Ros and Leon in a caravan park. We spoke on the porch of their permanent caravan. They were frequent hikers in the nearby hills and had once met a male hermit.

They were walking down a steep track on a cold day in winter, when the man just seemed to appear from nowhere. They described him as neatly dressed with a leather cap and handbag. The man then explained that he was on his way into town to buy groceries.

The couple asked the man where he lived. He told them that he was from the other side of the mountain. They then asked if he owned a property there. The man replied that he had lived for a long time by himself, inside a tent upon crown land.

[Above] Mt. Bogong 10, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

It amazed Ros and Leon that this man was obviously going to walk back over the hill, to where he lived, with all his bags of groceries. They said he looked very fit and sprightly for a man in his seventies.

The stranger related information about his life, such as that he had been in trouble with the police. He also claimed to possess secret knowledge regarding some murders.

"He opened up in the end, and then you couldn't shut him up; which was funny for someone that was a bit hermit-like," said Leon.

'I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could learn what it had to teach and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.'

(from 'Walden' by Henry David Thoreau)

Historical example: Medieval western hermits would often appear on pathways, while carrying a lantern. They acted as silent guides for lost travellers. Medieval hermits were recognised by religious orders as an official profession. Their duties were as pathfinders, lighthouse keepers and religious scribes. To escape the cramped conditions of a medieval village by becoming a hermit seemed an attractive option.

On my second day in Bright, I met a charming and erudite local historian, named Bernice Delaney. Bernice had worked for the Alpine Observer newspaper and also managed for many years in Bright two cafés named The Boiling Billy and The Cosy Kangaroo. She had often been charitable to local hermits, providing them with blankets and clothing.

Bernice remembered that many of the Bright hermits were experts at catching fish and rabbits. She would often give a lift to the hermits that were well known locally. She described one man, who carried freshly caught rabbits and also a large sugar bag filled with empty bottles, while also still managing to stick out one thumb.

Most of these hermits lived in humpy type dwellings along the river. There were some who had mental disabilities, which often made it harder for them to integrate into central town life. Some people even managed to live as solitaries in huts on the high country plains.

In more recent times, local councils have often tried to remove people who have resided unofficially. But many of these forest solitaries have proved to be unwilling to accept any offers they received of government housing.

[Above] Mt. Bogong 11, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

"They're the kind of people that Australia's losing," said Bernice passionately. "We want to socialise everyone, don't we? And we want everyone to look right and be right; it's normal. And we all think that's terrible about so and so. But there's got to be some free choice in there."

"It's like all those people - they're hermits, in a lot of boarding houses in Melbourne ... They're just living in a boarding house because there's no humpy type things down by the river."

Historical example: In North America, the Great Spirit beliefs made it customary for young males to live alone in a wilderness, where they would fast till the Great Spirit sent them a vision, which would define the purpose of their lives. Aboriginal tribes in Australia also required their young men to survive alone during a walkabout. Aboriginal elder people in Australia will also retreat in solitude to pay respect to sacred places.

'The end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time'

(T.S.Eliot)

After the discovery of gold in the 1860's, it became common for young males to live a hermetic existence within the hills near the Ovens River. Men lived purposely as solitaries within small tracts of bushland, where they hoped to discover great wealth.

Many prospectors were financially successful and they quickly took their wealth to the cities. Those who remained for long periods were usually able to eke out only a more meagre existence in solitude.

|

At the turn of the nineteenth century, a gold prospector named Peter McDuff lived close to the town of Harrietville. The location of this hut is only about eight kilometres from the ruined miner's hut that I inhabited in 1987.

McDuff's hut had remained remarkably intact prior to the 2003 bushfires. A youthful and respected Bright historian and conservationist, Andrew Swift, first discovered this hut in the 1980's.

McDuff prospected for years in a place known as The Black Hole, which is located in a dark and steep ravine. During the winter months, the sun will only shine in this ravine for a couple of hours. McDuff lived alone in The Black Hole with a packhorse and a cat.

The McDuff hut was three metres tall with a stone chimney. It had a small blacksmith's forge. The hut was built on a steep rocky spur at the point of a small, semi-flat peninsula that juts out over a large u-bend of the Ovens River.

When Swift first entered the hut, he found inside it a table with the pots and pans still in place. On the floor was a stretcher and hanging upon a wall was an old army trench coat; McDuff was evidently a veteran of the Boer War. |

[Above] Mt. Bogong 12, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

McDuff came from Scotland and was known for playing his bagpipes upon the rocky peninsula of The Black Hole. He could be observed wearing traditional clothing and walking about with military precision and stature.

"You can just imagine him playing his bagpipes on this rocky peninsula, sort of protecting his alluvial claims from other prospectors, who might venture into his domain," said Swift.

Andrew Swift can recall many personal associations with these solitary prospectors, who once lived in the valleys by the Ovens River. He has often found carvings of people's names and dates upon small tunnel walls, which provided an historical record of the isolation of these early prospectors.

"It's when you find someone's name scratched ... in a remote situation, you certainly get a greater sense of that individual, than you would if it was written upon a memorial board in town."

Historical example: Born in 1759 in Russia, St.Seraphim is one of the most popular of all historical examples of hermits. He was a monk that left his monastery to live in a forest. Many devotees would travel into the forest to experience the saint's gentle wisdom. Seraphim tried to hide the path to his hut with branches and would lay face down as people approached. He had a reputation for sharing his food rations with the animals in the forest. In return for this kindness, a bear brought him wild honeycomb wrapped up in leaves. There are many other examples of hermits making friends with wild animals. There is one recent story of a recent Himalayan religious hermit, who became a friend to some monkeys. This hermit apparently acted as a mediator in the quarrels between monkeys. As a return payment for this hermit's adjudication skills, monkeys apparently threw down food from the trees.

[Above] Mt. Bogong 13, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

SECTION 3: ECO-HERMITS

'Few places in this world are more dangerous than a home. Fear not to try the mountain passes. They will kill care, save you from deadly apathy, set you free and call forth every faculty into action. Even the sick should try these so called dangerous passes, because for every unfortunate they kill, they cure a thousand.'

(late 19th century Californian author, John Muir)

"Unless you save the whole thing (the earth), you can't save any of the pieces. So any attempt to be saving a little piece here and a little piece there can only be seen as a kind of prayer."

(John Seed in an interview with Ram Dass)

Eco-hermits are solitaries who are dedicated to living - as much as is possible - in harmony within nature. Their self-disciplined lifestyle focuses on reducing consumption to absolute need and also making use of re-cycled materials.

It was Diogenes who said that the gods gave men an easy life, which they then spoiled by seeking wealth. For eco-hermits - like all hermits - their ability to pursue a goal both spiritually and materially is a necessity within such a solitary lifestyle. For eco-hermits, their key focus is trying to protect the area that they live in, while also helping other people to appreciate the unique nature of a landscape.

The following is an interview with Barry Higgins by Stewart Nestel, which occurred in early spring of 2003. A friend of Stewart's (Chris Trengrove) first met Barry while walking in the forest near Katoomba, in the Blue Mountains National Park, New South Wales. Barry lived in the forest in a dwelling that was self-made from wood and corrugated iron. The dwelling was located within view of a small walking track.

He initially began living in the area as a member of a protest group, which campaigned to prevent the development of a large resort near a township in the Blue Mountains. The group were successful in their campaigning, when the case went eventually to court. Since then Barry has remained living within that region of forest that borders the National Park.

[Above] Mt. Bogong 14, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

The interview occurred on a wet afternoon. On the recorded soundtrack was a steady sound of rain upon sheets of corrugated iron. At the beginning of the tape there were also the sounds of Barry stirring cups of tea in metal mugs, which he then shared with his guests, Stewart and Chris. Quite frequently, Barry paused in mid-sentence as he spoke, as if he was waiting perhaps for the best choice of words to arrive in his consciousness. He often also gave a dramatic emphasis to a key word within his conversation. He possessed a forceful, slightly American accent. Barry has a degree in fine arts.

A small author's aside: Barry - like many Australians - calls a forest area "the bush". This reminds me of a comment I once heard by a visitor from Indonesia, who was staying at my home. I had offered to take her walking in the bush. She replied, "Where is this one bush that people keep describing. It must be a very special bush".

This interview with Barry Higgins occurred as part of a radio feature on hermits made for the ABC Radio National program 'Radio Eye.' That program was co-produced by Stewart Nestel and Peter Davis, sound engineer was Angus Kingston (ABC RN) and Executive Producer was Tony MacGregor (ABC RN).

INTERVIEW WITH: BARRY HIGGINS

Stewart: Would you describe how you came to be living by yourself in a forest?

Barry: Since the journey up the mountains started, I've spent in the last three years over half that time living in the Katoomba bush. The rest of that time, living I spent in Tasmania. It's been many years coming back and forth working in the green movement: saving the forest, fighting for land rights and reconciliation with our Aboriginal brother's and sisters…

I can spend six months out of the year in Tasmania. And Tasmania's pretty tough going because nine months out of the year it's so cold, and that makes it difficult, living out. But in Tasmania there are some other people there: tree sitters who climb trees and build platforms, people who build humpies, tents and tepees. They're people who ... love the outdoors; bush people who don't need four-wheel drives. They survive on their wits. They've got an objective. Any tree saved is like a pensioner; you know, like you wouldn't cut down your pensioners…

Now I live by myself in the Katoomba forest. I've ceased to become a member of any group, any consensus or enterprise ... that isn't my own heart felt principles ... I belong to the land.

[Above] Mt. Bogong 15, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

Stewart: Besides your work as an environmentalist was there another concrete, a cathartic reason, why you decided to continue living in the forest this way?

Barry: It wasn't an epiphany, like all of a sudden I came to some spiritual, mystical decision. It was more like the way some of the eastern traditions look at life: wisdom is from knowing what not to do ... I knew what I wanted to get away from. I was living and paying rent, becoming tense and competitive. And unhappy - turning into some kind of machine: owning things, buying things, and I felt that that was actually an endless and pointless place to be ...

And the stimulation to move away from the city into the bush was basic needs. I was getting sick more often, eating food that was making me irritable. I felt like I needed to relax more. In the city I was always motivated by the clock - racing and running to get somewhere.

Stewart: How would you describe your routine out here?

Barry: A routine? A regimen? The sun comes up and then it gets replaced by the moon. The sun goes down, the moon comes up. Those are the regimens. That's the daily process. Some days are more productive than others and some days you're not doing very much. You're filling your time by simple things like reading or resting, exercise, breathing. There is a natural rhythm that nature teaches us, that everybody has the potential for ...

Time is rather abstracted when you take your watch off… Your mind almost goes blank. Every day you try to replace the problems that you've been going through with solutions. Clear the deck, cleaning your head of all the social structure of the commercial and capitalist world: the monetary and the military - what's falsehood and what is prophetic. I sort out all the problems of the world and how I relate to them - the people. Philosophy is my stable-mate. Take it down to just being a decent, generous, loving, kind person - give until it hurts ...

And coming out and living in the bush, you just automatically let go of all your built up images: the ghosts, the fear of the dark. You know, the incursion and invasion of monsters, all that, those childish dreams ...

It's a kind of a natural progression. It's the lessons that you must learn, that nature will win. It's always you that has to learn to adapt and change ... Nature wins, because nature changes and it adapts to live ...

[Above] Mt. Bogong 16, Nth. East Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Peter Davis, 2005)

At one time, this was a forest plantation, and they used to plant all of these pine trees here for that purpose, but that's been gone sixty years. The pines trees are still here growing right alongside the eucalypts. And the funny thing is the birds: the yellow-tailed black cockatoos eat the pine cones as though they were an indigenous, integral part of their diet ...

I suppose all the bush walkers bring their own perspective on it. Ah, I always have a smile when I see the bush walking clubs come out here, because they're often decked out to the nines in their K-Mart camping gear. (Barry laughs) 'Course none of that stuff in my opinion is really good for more than a 24 hour thing.

CONCLUSION:

A forest can seem a harsh place, as it is unforgiving when people are inadequately prepared to live there. A forest does not focus upon the singular desires of a person like a space that is enclosed by walls. Camping by myself in a forest much later in my life has enabled me to understand how my period as a hermit influenced the rest of my life. Being a hermit can teach us discipline, particularly about the need to perservere through a hard situation, when there is nothing but our thoughts to encourage us.

A life of solitude in a forest can allow an escape from media corporation bias and social conventions. A hermit can

have weeks where they forget about money and also never hear a grim news report. Instead, a hermit can begin to listen more to the voice of the wind. A hermit can become more humble, when they intimately realise that their own survival is dependant upon the moods of nature. The spirit of a forest can heal us, if we become submissive to the dominant force of nature. We can take our injuries to the forest and if they are not too advanced, then our injuries can be healed. Solitude in a forest will reveal all our fears and strengths. The forest will teach us to view our thoughts with equanimity, because through solitude we observe the habits and cycles of our thoughts. Spending time alone will grant us the humility to know that our thoughts can be either wonderful or very ordinary. We can learn as hermits to ignore our habitual thoughts and concentrate rather on one immediate thought (issue) in the present moment.

Being alone can make us feel depressed, yet aloneness can make us happy. A hermit chooses aloneness. A hermit is one who is prepared to be disciplined and wait patiently for the benefits of solitude. A hermit may not always need physical solitude; what they require most is solitude within the mind. It is an old saying that we all can be alone with our thoughts even in a crowd. A hermit who is peaceful can pass on their contentment to others even if they do not speak. I wish all readers luck in finding a bit of that happy-contented-lonely feeling.

'The physical domain of the country had its counterpart in me. The trails I made led outward into the hills ... but they led inward also. And from the study of things underfoot, and from reading and thinking, came a kind of exploration, myself and the land. In time the two became one in my mind. With the gathering force of an essential thing realising itself out of early ground, I faced in myself a passionate and tenacious longing- to put away excess thought forever, and all the trouble it brings, all but the nearest desire, direct and searching. To take the trail and not look back.' (20th century author and journalist John Haines)

Sources and References:

Into the Wild, Jon Krakauer (MacMillan, London, 1996)

Pelican in the Wildeness by Elisabeth Colegate (Harper & Collins, UK, 2002)

Hermits: the Insights into Solitude by Peter France (Chatto & Windus, UK, 1996)

Odeon the Intimations of Immortality: Complete Poetical Works of William Wordsworth, (MacMillan and Co. London, 1888)

Mountains of California, John Muir (The Century Co. The DeVine Press, 1894)

The Wanderer : Christopher Brennan: Portable Australian Authors, Edited by Terry Strum, (University of Queensland Press, 1984)

(John Seed in an interview with Ram Dass) http://www.users.on.net/arachne/hermit.html

Research and interviewing by Stewart Nestel and Peter Davis.

About the Writer Peter Davis

|

Peter Davis is a freelance writer and radio documentary maker. He is studying writing and editing at RMIT. Peter has had two plays produced: 'Letting in the Lion', Universal Theatres 1995 and 'Positively Everything', broadcast over 6 weeks on national community radio program, 'Out and Out.' He won the Community Broadcasting Association of Australia award in 1995 for best Information documentary for 'The Joan Golding Story'. He has produced regularly as a freelancer for ABC RN including 'Poetica' and 'Radio Eye'. He co-produced a documentary about hermits for Radio Eye (ABC Radio National) in 2005. Peter lives in a small town in Victoria; a place where he can walk a few minutes down the road and be in a bit of forest. |

[Above] Photo of Peter Davis by Peter Davis, 2005.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.11 (June, 2006) |