How my self-adventure of living with HIV/AIDS began

I caught the HIV virus in 1986 when I was nineteen. This is my story of how I became HIV positive and then healed myself creatively.

In 1985 I had deferred from a science course at Melbourne University. My desire back then was to travel first and generally learn about life. I knew little about HIV/ AIDS.

After six months, I returned to Melbourne but not to the western suburbs, where I grew up. I got a job pouring drinks at the Prince of Wales Hotel in St.Kilda, which had live bands and also a gay disco on Sundays. Initially, I just enjoyed the bands.

I soon had my first night with a sexually experienced man. Where I grew up, people, especially my father, were fairly non-accepting of homosexuality. I had a lot of guilt to find myself desiring a male, and to overcome that - well I guess I drank a lot that particular night.

When the man offered to use a condom, I refused. It was like I needed to abandon my sense of responsibility, so I wouldn't have to feel the guilt. I wonder now, why don't people discuss safe sex calmly, at an earlier stage, when on a date? Making decisions in the heat of the moment is very different to the cold light of day. There is a sense of further permissiveness during sex, when the level of arousal gets high.

In the spring of 1986, I started night classes in preparation for my return to uni. and met a girl, who was traveling to Melbourne from Sydney for her holidays. We found a flat together in summer. We started practicing unsafe sex.

That Christmas, my mother suddenly re-contacted me after two years of separation. She had separated with my dad about the same time I had left my parent's home. Mum then paid for a short holiday in the country for us to catch up together.

The night we arrived there, I became dizzy, got a fever and became delirious. It happened that quickly. The wind had maintained its sense of humour. I woke from a dream washed up on a salty bed. My flesh was at high tide: rock pools formed on my chest and little fears shone in the moonlight.

My mother is a nurse and she intuitively realised it was serious- she took me straight back to Melbourne. We visited a GP. A few days later I was staying in what was known as the AIDS ward at Fairfield Hospital, without the strength to move from bed. My high fevers lasted a week.

HIV Fever

I awoke again and again in fever- from and into the same dream- and studied the still hospital room. Found that there was nothing unnecessary to see, except perhaps for the TVs and also painted on the floor in the nearby corridor, one red line that signified the border between the separate wards.

|

So I waited patiently in the hospital bed - through each dawn - for a time when I could sail upon a raft made from a pill-tray. You could hear the laughter of a large syringe as it descended (as if from the sky) toward my arm (like a parachute). I began to see strange things regularly.

Usually, I saw hundreds of little particles floating around inside the light. My doctor said these were dead matter upon the surface of my eyes. They were beautiful dead molecules that were shaped a little like paisley.

In fever, my consciousness had sort of abandoned itself to the abstract pleasures of fever. My consciousness needed to make very little efforts. My consciousness was getting beautifully and tenderly screwed from behind by its subconscious self. Sometimes, my visions seemed more like pleasure moans.

At night, I felt my vision fade into the softness of light. I remember staring for hours at something like the movement of a faraway ocean shore, which later was just a reflection of a neon light on a wall. Beyond the one large window, I could see trees in the night wind, which seemed to move like they were miming to me. |

[Above] Blue Shot (Photo by Kleo Dogaris, year unknown)

I often became dizzy during fever. It was a similar feeling to what people get on the floating jetties at Circulay Quay in Sydney. I felt - while remaining still - like I was gliding around in semi-circles. It was heady in an 'I think that I've had too much of something illegal' kind of way.

It could get scary sometimes - like vertigo. I'd get an urge to call for someone to come and hold me - to stop me. My girlfriend described this experience to me, after my temperature had finally dropped. She had remained for most of each day at the bedside.

My mind and body were probably awash with very high levels of the virus back then. I spent two weeks in high fevers. I remember now still how my hearing had changed - how words of people speaking to me seemed to just float past - like subject matter in protoplasmic streaming.

I dived into dreams, three breaths below the surface or more. I yelled out sometimes. My heart grew like bamboo into 1000 feelings. I am a lay Buddhist. So Buddha's thoughts were both the left and the right pumping action of the heart.

I promised to myself, back then, at nineteen, a beautiful death and I guess in response - as some mercy - strange visions began like a flood. At first they pitter-pattered upon my young-old mind, which began to sag like a roof, unequipped for the heavy rains of wisdom.

And as the angels spun, high above upon the top of tornadoes, throwing down tomatoes, I felt both light and ready.

I produced rivers of sweat, which flowed from the spring of my body. My main memory from these two weeks of fever is laying in wet bed sheets and waiting. A nurse would come yet again to change the bedding. This usually happened a few times each day, around that time the Panadol was wearing off.

I followed in my fever, visions, a kind of pathway, a winding direction. It led to a dark and yet familiar ramshackle place, where the particles all played on their first name basis. There were times when I'd hear my lover's voice calling me. But she then kept slipping on the thin surfaces of light - much like the sluice from my entangled drip-stand, through which we could jump and dream.

When the fever ended, I had a headache for a few days. Rudely awakened by a bedside light, I would see social workers with old socks on their shoulders, who became the spheroidal gaseous envelope surrounding my heavenly body. And I guess I was surprised to sense that all food tasted real here inside hospital - like nothing advertised. I remember that my mouth felt dry and sore to sound. My skin was desert red and yellow.

Finding out that I was HIV positive

I can remember upmostly, two things from my initial stay in Fairfield Hospital. One memory was the sound of lyrebirds in the grounds outside the window at night. The other thing I remember clearly was the day of my discharge, when a doctor asked me a lot of questions - I remember lying to this doctor about never having had sex with a man. The lie made no difference of course to my blood tests.

I had to wait six weeks after my initial discharge for my HIV test result. This wait included two visits to an outpatient clinic, where each time my result had not arrived although I'd been told it would.

I rang the third time - just to make sure. The doctor seemed to already know the results and I was very pushy. He said, "Well, I guess if I demand you come in again, you're probably going to know what it is anyway." After the phone-call, I went and told my girlfriend, who was then sleeping.

I thought I knew back then what HIV/AIDS meant. It was 1987 and the chilling Grim Reaper television commercials - more like a short horror movie - had been broadcast. I believe these commercials taught me that HIV meant AIDS and that AIDS meant death.

|

Perhaps, I didn't know what to think. At 19, I was just starting to wonder what life meant. In a melodramatic frame of mind, I sold most of my things and also gave away my vinyl record collection, which is the only event I still regret!

My girlfriend and I gathered money to travel around Australia for what I thought might be one last time. My girlfriend then tested HIV negative.

I didn't receive any counseling at the hospital after my diagnosis. It was very early back then in the epidemic and things weren't very organised.

When I asked my poor doctor the cliché question, he responded that I might have five years to live, maybe many more - they just didn't know enough about the disease yet. Sitting there in his surgery room, I felt like an actor on stage without a part - only saying what I thought I ought to. The doctor suggested that I report for blood tests every three to six months in a capital city.

When I told my best friend about my HIV status, he hugged me and cried. He suggested that I keep a journal and record my thoughts, whilst traveling. Then in a small camping park on the east coast, I wrote my first obscure poems. It was by writing creatively that I was able to find at last some calm and a place to release emotion. |

[Above] VACCHO : Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation.

On our travels up the coast, my girlfriend and I went through the cycles of grief, self-pity, self-abuse and fear. A year after my diagnosis, my girlfriend and I then separated. This was the hardest stage of my living with HIV.

A few months after the separation, I traveled again around Australia and lived mostly this time by fruit picking. I also stayed for six months in a tent on a mountain in North east Victoria, sorting my thoughts slowly like a hermit does.

Then my mother sent me a book in the mail, which had been mentioned by a man with AIDS, who had appeared on the channel 10 news in Melbourne. It was a book about healing yourself with immune therapy, meditation (which I was already doing), massive doses of vitamin C and Chinese herbs; it was the first bit of hope. There weren't yet any effective pharmaceutical treatments.

Getting on with my life

In 1989, I met a beautiful man, a gay rock musician, who was HIV negative. He was a very tender and intelligent force in my life.

We had a six month relationship, which probably would have been able to last longer - but I still felt a lot of guilt about kissing a man, being tender in public. I don't know why I was like that with him - except again to perhaps point to my urban and conservative upbringing.

When this love ended, I began to wonder more about my true sexuality. Men appealed to me but not quite as much as women did. This fact resulted in my restless feeling during a gay relationship, which was not easy to overcome.

I was a bisexual, who seemed to be more comfortable in a relationship with women. Some people would always call this - 'bisexuality' - being confused, I guess. But I would prefer to think that I actually achieved less confusion about myself, through my period of youthful sexual experimenting.

Also in 1989, I met John Marriot, the brave man who appeared on the news. We met at a private clinic in Melbourne, which HIV/AIDS patients attended for injections of mistletoe and vitamin C.

John was a fun and wealthy interior designer, who lived each year six months in San Francisco and six months in Melbourne. He organised a peer support group of HIV positive people, which convened in a member's flat in St. Kilda. All the other members of the group were middle aged, gay guys in their forties.

John had the latest information from the USA about HIV and complementary therapies. I usually sat still and listened very quietly, perhaps scared of the lesions on some of their faces.

John believed in sharing our creativity as a method for healing. What I remember most is John's guided visualisations, where he would read aloud one of his short stories to the rest of the group that had their eyes closed.

Each story climaxed with a scene where we met a figure, which usually turned out to be ourselves. Our visualised figure would then perform some action, which required creativity and self-belief. Finally, we described, one at a time, how our stories ended.

Loss and grief and finding a way to cope with these issues

By the early 1990's, everyone else in that group died in a soft-shell peace. Most had lived longer than their doctors had expected. Multiple grief is especially hard because our loss is not connected to one individual. What we are feeling becomes harder to define. There seemed too many funerals to find tears anymore.

I wrote a play about my experiences in that peer support group. There were strong themes to write about HIV/AIDS: time represented the collapse of immunity in our bodies; the closer we come to death, the more honest our words become.

HIV positive characters are inconsistent, contradictory as they lived and died in social conditions often without harmony. The way people cope with their own disease progression is not arbitrary to the reactions of people that surround them.

My favourite example of a play inspired by HIV and AIDS is Tony Kushner's, 'Angels in America'. This play managed to combine political message, a broad social context and also fantasy. These were three important paradigms about the experience of living with HIV/AIDS, which needed to be represented together.

Representation of fantasy as part of the HIV living experience was particularly refreshing. Many HIV positive people utilise fantasy as a way of both escaping from and also managing their fears. We fantasise about a particular body image, when our own physical self is changing. We include fantasy in safe sex practise to increase enjoyment and encourage safe sex compliance. Early in the epidemic, a lot of positive people also fantasised elaborately about their funerals, planning each detail as a way of approaching their mortality.

The HIV/AIDS community and its art

A favourite example of creativity concerning HIV/AIDS is the AIDS Memorial Quilt Project, which commemorates the lives of the deceased. The project consists of quilt panels, each the size of a cemetary plot, which are designed and made by loved ones. There are no strict rules about what each panel may contain.

|

The panels are grouped into blocks of 12 by 12. There are spaces between each block, where people can walk. By the mid 1990's in Melbourne, the HIV positive community needed the large space of the Exhibition Buildings, due to the amount of panels being displayed.

The feeling you get, when walking amongst the quilts is like being enfolded by life details and warmth. The quilts are a life celebration. Details that I can remember are: pieces of clothing; pictures of pets; teddy bear noses; favourite quotations; a joint inside a plastic bag. I also read about a quilt, which contained a staff of music containing no notes, only a single rest. Another panel contained a large ripped hole, where a visiting family member ripped the surname sewn by a lover.

In the mid 1990's, I joined an HIV activist group and also became a board member of the Victorian AIDS Council. I learnt a lot during this period. For example, that the goal concerning HIV/AIDS was to end the epidemic and not always to create artwork that would live on and be considered transcendent.

'We need to be simple, but not simplistic' -- Douglas Crimp, ACT UP |

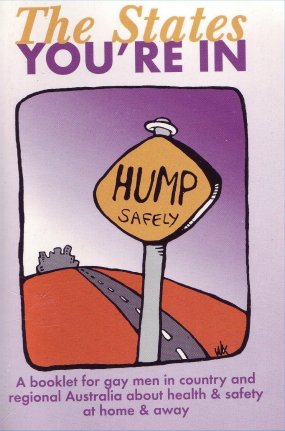

[Above] The States You're In: Hump Safely, Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations (Artwork by Sue Wicks, year unknown)

HIV/AIDS education requires visual art messages to immediately grab attention. Striking images result in people being interested in reading the extra information. In the case of the Beats Campaign, which was conducted in Australia to educate men about safe sex at beats, a series of mock road signs were employed: 'Safe Sex Ahead!' and 'Condoms Next Nine Inches!'

In the mid 1990's, I also joined a community group called People Living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) Victoria. Together with a handful of HIV positive people, we produced a radio program at 3CR called 'Positively Primed'. The intention was to provide our stories to the broader community and also support and educate one another. My most moving memory of this experience was recording a telephone interview with a hospice worker in Zambia, Africa, who described first hand the decimation of lives at all levels of their community.

Burnout became a great problem for many people in the HIV community, including myself. The fight against the AIDS epidemic is so huge that it is hard to slow down and pace one's personal involvement with it. I was involved in many things: weekly community radio program, speaking to school groups about living with HIV and also a lot of committee work.

In 1993, our HIV community radio group decided to produce a comedy serial. With a $500 budget, we produced seven episodes (each 15 minutes) called 'Positively Everything', which was about a telephone dating agency run by Baby Jane, a male to female cross dresser with a drinking problem.

The following scene takes place between Baby Jane and his friend, Ella Highwater, who is also a cross dresser and an old movie buff. The scene occurs the morning after Jane has practiced unsafe sex on a date whilst drunk.

Stage direction: Ella and Baby Jane are now facing each other with some intensity.

Baby Jane: And that's how it ended, Ella. To cut it short, we rooted like two dogs in the back of his Honda Civic - before I could get a hand on the condoms. And without me telling him that I'm HIV.

Ella: Ohhh!!!!

Baby Jane: Oh, Ella. What should I do?

|

Stage direction: Ella takes a tissue and wipes Baby Jane's face.

Ella: Now, darling. I'm not going to lecture. But you are going to have to phone your young man, give away your little secret and see what the two of you can work out together.

Baby Jane: But, I don't think I'm able to. What am I meant to say? "Hello, darling. That was great last night. By the way - did I happen to mention anything about HIV?"

Ella: Did he? Darling, it takes two people to not use a condom but only a well-trained chimp to put one on.

Baby Jane: Oh, but I can't.

Ella: Yes you can. There's no time to lose, Baby Jane! Give it some of the old Katie Hepburn guts and determination.

Baby Jane: But-

Ella: Guts and determination, my dear. (Katie Hepburn-like voice) Fire up the starboard engine, Charley. We'll get this old queen back on the water yet. |

[Above] Positively Sexy: Women's HIV Support and Health Promotion Unit, ACON (Aids Council of NSW)

I wanted to create a play where being gay is perfectly natural, being transgender is absolutely normal, and being HIV positive is a lifestyle. 'Positively Everything' was broadcast nationally on "out and Out'- a funded gay and lesbian program. Six of the HIV positive actors in that project have died. In 2004, I did a major re-write of this production to tackle the new increase in HIV infections in Australia partly related to crystal-meth amphetamine usage.

Since 1994, I have now produced four documentaries for ABC Radio National ('Radio Eye'/ 'Indian Pacific'/ Poetica). Three of these involved me disclosing my HIV status to a national audience. In 1995, I also appeared on the Bert Newton TV program and spoke about being HIV positive. It is important for me as an artist to be open about my HIV status. Art is about freedom and longing, which means that I cannot feel fully creative when I live in secrecy. My next documentary 'In search of the hermit within' will air on 'Radio Eye' in early 2005.

Getting to know myself as a long term survivor

In 1994, I had married a very supportive and creative woman, who is HIV negative. Her name is Kleo. We met in Melbourne's west at the Footscray Community Arts Centre, FCAC).

Kleo and I were both cast members of a theatre production at FCAC about a local supermarket. She was cast as a checkout operator and my character was a shop thief, who would also busk outside the supermarket.

Kleo and I had one romantic scene together in 'Shop Therapy'. It involved a comic moment, where I had to stuff some large tins of dog food under my T-shirt and then act nonchalant. The size of the tins made my belly seem huge and obvious. But Kleo's character took pity on me and ignored my theft. After paying for a packet of chewy, my character then impulsively kissed her.

In real life, I never believed that I would possibly kiss Kleo because I had HIV. My immediate assumption was that she didn't have the HIV virus. And for years, I had believed that anyone who was HIV negative would not desire me if they knew my status.

I remember the way that Kleo looked the first time we met - the beautiful and antique lemon and green dress, which she wore to first script rehearsal. And the way her eyes looked sensitive and yet also very open.

We got to know one another gradually at first. During this period, a close friend of mine, Phil, was slowly dying of AIDS in hospital. One day, Kleo came with me to visit him. It was a few weeks after this visit to Phil that I told Kleo about my being HIV positive. At the time, Kleo had felt guilty about her first thought in response to this news. She confided later her first response was, 'Damn! But you're so hot.'

It was near to our production date, when Kleo told me that she had feelings for me. She had invited me out to a park on the false pretence that we were to practice our lines in the play. When we were sitting under a tree, she kissed me three times. Our kisses were much more than our quick peck from the love scene in the play.

A week later, we needed to make an appointment at an infectious diseases clinic located at the Royal Melbourne Hospital. We spoke to both a counselor and a doctor. They both advised that many people had relationships who were sero-discordant (positive-negative).

|

We were shown graphs and medical statistics about such couples, where the risk of transmission proved to be negligible, when the couple always used a condom together with water based lubricant. We were told that oral sex was considered to be extremely low risk regarding HIV transmission - less than 1%. We decided not to practice oral sex.

We were in love and very relieved to know that our expression of love seemed possible. But it would take three more years (1994) before we could get married and live together. Kleo's parents have orthodox religious beliefs that are very strict. Initially, her father would hang up the phone whenever I called. So I would hide in some bushes opposite her house and wave an arm in the air on the half hour until Kleo appeared. We could never hold hands in public.

We eventually got sick of this arrangement. In 1992, we traveled overseas together. Kleo told her parents that she was going on a study trip as part of university. She is a photographer. I wrote a lot of poetry after this holiday. Creative writing became a new way of meditation for me. It would calm me to sit for hours dreaming into a computer. |

[Above] VACCHO : Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation.

This slowing and concentrating of my thoughts, I believe, helped to release toxins from my body. My HIV-related blood tests at the end of 1992 were the best results I have ever received.

When we got back to Australia from our holiday, Kleo separated her developed photographs of our trip into two bags. One bag contained shots of scenery for her parents to see. This bag also contained shots where Kleo had posed with some other backpackers - her supposed fellow university students. Into the second bag were placed all our lover's shots taken with her camera on automatic time.

The day I collected Kleo to see the photos was also the day she would receive her first HIV test result. She was very nervous. As she left her parent's house, Kleo picked up the wrong bag of photos and left our cuddling shots for her parents to see. At least that day she tested HIV negative.

'Is the AIDS epidemic over?' asked an Australian TV journalist.

They were interviewing Professor Peter Piot (Director of the WHO UNAIDS program) in 1998.

Professor Piot's answer was, 'Definitely not!

The professor continued to say later, 'The global epidemics of HIV and AIDS do not affect all groups and all regions equally. Instead, they exploit the fault lines of an already profoundly unequal world.'

HIV in Australia

In Australia, there has been a recent rise in the annual number of new HIV infections. Numbers here are still very small compared with Asia and Africa. What is disturbing recently is the emerging threat of HIV/AIDS for Australia's Indigenous communities. Indigenous Australians have never had equal access to quality health services, when compared with the rest of the population.

'The Aboriginal infant mortality rate is still three times higher than for non-Aborigines. The life expectancy remains at least 20 years less than that of the non-Indigenous population…' Gary Lee, Indigenous Gay and Sista Girl/ Transgender Project Officer at AFAO (National AIDS Bulletin, Vol.12, no.3, 1998)

Art is very important in spreading the messages about HIV/AIDS within Indigenous communities. Tragically, HIV/AIDS has already resulted in the early deaths of a number of talented Aboriginal artists.

Hope is derived from the fact that Aboriginal art has long been connected with social messages and the depiction of spirit within communities.

The role of Aboriginal art: 'is more profoundly holistic, that is, than art's role in a compartmentalised Western culture.'

Maurice O'Riordan (National AIDS Bulletin, Vol.12 no.3, 1998)

In 1987, Andrew Spencer Tjapaltjarri's (Walpiri) painting, 'AIDS threatens Aboriginal Life', utilised ancestral drawing and figures to warn of the threat of an HIV spread between desert communities.

Another example of indigenous artwork in response to HIV/AIDS is Robert Ambrose Cole's (Luritja/ Waramunga) strong painting, 'Spirit'.

'In traditional Aboriginal society, diseases were generally seen as having magical or supernatural causes. Thus, Aboriginal modes of treatment occur within an all-embracing context of mythology and social organisation.' Gary Lee (NAB, Vol.12 no.3, 1998)