STUART HIGHWAY ROADKILL ROOS

By Coral Hull

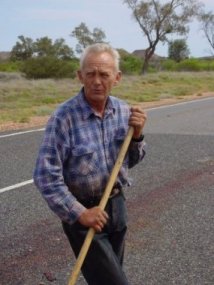

[Above] Roo-44, Pine Creek to Katherine, The Stuart Hwy, Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

The Stuart Highway is a single road that runs from north to south and south to north, spanning the width of Australia from Darwin to Adelaide. It is 2,690 kilometres (1,671 miles) in length. The road is a 'civilised' strip of bitumen but is still said to cross some of the harshest and most inhospitable terrain in the world. While adding the final touches to a book of poetry The Straight Road Inland on my last trip from Sydney through Port Augusta and onto Darwin, I noticed the hundreds of dead kangaroos on the sides of the road and off into the scrub. During my time in Darwin, I couldn't seem to get them off my mind. I was intending to drive back to Sydney via Queensland (via The Barkly Tablelands) a few months later, which cuts the trip from Darwin short by 200km.

But instead I made a snap decision to drive back down the Stuart Hwy in order to photograph every single dead kangaroo who still had a face. I decided that I wasn't leaving the Stuart Hwy or going back to Sydney until this was done. I ended up on the road for 5 days and got a lot more than I bargained for. It was a bizarre physical and emotional experience, what with avoiding 4WDs, roadtrains, the heat, flies, maggots and the rotting corpses that give off the stench of LPG gas. But my brief experience holds no comparison to what those poor animals must suffer when they become the victims of human traffic. These words are a combination of factual commentary and note taking from the 5 days during 2001, that I spent alone photographing the roadkill roos.

Notes: There was a point where I seemed to lose a sense of all consciousness, where I barely remember holding the camera. It was as though I had given myself over to something greater. It was a combination of the trauma, the death, the ghosts of the dead, the land, god, the prescribed drugs (pain killers) and the act of creation that I fell into. Later when I looked at the self portrait photos I saw that in some I looked dead. In comparison the kangaroo corpses along the strip were coming to life. I named them while I lost consciousness.

It was as if we were combining somehow, exchanging places as that which is energy interwoven. I associated this deadness and aliveness with having empathy for the dead kangaroos and also with entry into some kind of psychic state (trance hypnosis). Aside from this there was no similarity to be drawn between our situations. I had merely been an observer after the fact of their acute suffering, while shaking my head at this tragedy.

|

Much of my creative art has been about reaching beyond my own perception and into a distant landscape of reality or truth. It is a goal that perhaps as creative artists we will never achieve. Some argue that we are merely ourselves and that the only way we can perceive is subjectively, from the self. In a spiritual sense there seems to be something amiss here. If everything is interconnected as I believe it to be, then surely in some ways we must share the one consciousness. If this is the case then surely a veiwpoint can slide from subjectivity to objectivity. I knew that while I could never be them or feel their pain, the pain I felt when I thought about the many who suffered was acute and at times unbearable. The opposite of this was ecstasy. |

[Above] Map of the Stuart Highway, Australia (Image by artist unknown, year unknown)

I recently had the privilege of hand feeding a group of black angus cows some hay in the drought of New South Wales and watching them eat. I was completely lost in that present. I will look back on it as one of the great moments in my life. To fulfil a need of physical hunger in another was to fulfil a need of hunger within my own soul. But to my way of thinking, there was a reason I had to get beyond my own subjective perceptions and that was because they were flawed. In 2000 I had 'diagnosed' myself as suffering from complex PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) although I do not like the word 'disorder', that I had struggled with at intervals throughout my life. At that moment the first large chunk of the complex jigsaw puzzle of my flawed psychology fell into place.

I looked back on all I had created and it was full of the serious sense of trying to cope and make sense out of the world (as an external physical reality as independent from my psyche) but through the eyes of who or what, I wasn't quite sure. My life had been weird and preconscious. But there were so many wondrous aspects, the grasp of multiple concepts, the trips into the light, the speed and intensity of the creative process, the loss of consciousness, the perpetual inner dialoguing, the sensory storms. Out in the desert spaces, I could let myself go. I could wander through the landscape as though it were my psyche. If I got lost, which I often did, no one would know about it. I wanted to be myself and not myself. I desired love attachment and self dissolution.

I drove out of Kakadu National Park where I had been photographing for a few days and stayed in Nitmulik (Katherine) for the night. I took some photos of dead kangaroos along the Stuart Highway from Pine Creek to Katherine covering a distance of 89kms. I took 87 photos. This took 5 hours. The next day I drove from Katherine to Elliot and took photographs of all the dead kangaroos who still had a face. They were numbered 88-327 = 241. My primary concern has been on completing a photographic project documenting the remaining 'individuality' of kangaroo roadkill along the entire length of one of Australia's longest single stretches of road.

It wasn't long before I settled into a strange dissociative process or parallel reality, whereupon I began to see myself as 'a roadkill expert'. I am now able to tell you where the most lives have been lost from one end of Australia to the other, including the differences in density and the variation of species which would show nightly movement and migration patterns. I am able to talk about the etiquette of outback highway travel and where the best roadhouses are located and why. I am also able to tell you how to avoid hitting a kangaroo while driving on Australian roads. Some of what I was involved in on this trip has been lost to me and I wouldn't be able to tell you what I was doing in every moment. Since I was also an expert at shifting my own states of consciousness.

[Above] Roo-2034 (The Crucifixion), Marla to Glendambo, The Stuart Hwy, South Australia, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

I drove from Elliot to Renner Springs and took photographs 328-676 = 349. At one point a road train (53 metre long truck) passed within a few feet of where I was working and ended up blowing the hot air, exhaust fumes, flies, burning rubber, gas and the maggots that usually inhabit a decomposing corpse onto me. By documenting these corpses for approximately 3,000 kilometres I wanted to play the camera by zooming in close. I wanted to find the essence of them, some meaning for us all. Inside the deep grief and despair had become inaccessible.

I wanted their brief life and tragic death to have meant something. I wanted their agony to perhaps teach us about agony and why it is wrong to inflict pain on another. I am trying to empower these kangaroos, to have them remembered and their lives mean something. For I loved each one of them as I loved myself. It didn't matter to them that I was out on this highway doing this work, but perhaps it would matter to someone sometime, or even save the life of a future kangaroo. Was it better that someone cared than have no one care at all? Perhaps so, but in the end I had to go past the thinking and feeling and just keep photographing, until through sheer physical and emotional exhaustion the work became a mere process. Did I then betray them?

I was acclimatised to the heat after having been in Darwin for awhile, but I was unwell with shingles, not knowing that they were a precursor to the life sentence of CFIDS (Chronic Fatigue Immune Deficiency Syndrome). I was on four lots of medication in order to keep myself upright. This made the situation all the more surreal. So for the rest of that day I only photographed for 5 hours. As I drove and photographed, time slipped away and became non-time. There were that many dead kangaroos that things almost became too easy. Perhaps the roos had had that very same thought, as they crossed that tiny section of the highway - too easy.

I drove from Renner Springs to Ti Tree and took photographs 677-1085 = 409. I got sick on the fourth day from breathing that shit in, but I did not want to stop. Some places, such as by the roadhouse at Renner Springs, were so thick with roadkill, that I was photographing for well over an hour and when I looked back the roadhouse was still in sight! I was so absorbed in the process, that I didn't notice that I haD moved less than a kilometre. Tourists soon learnt when visiting Australia that the dead are far more visible than the living.

Notes: I drove from Ti Tree to Alice Springs taking photographs 1086 - 1790 = 704. Then, just when I was starting to count the roos in a methodical way, something broke through. The pain was acute. There was this one particular photo. I looked at what I missed sticking out of the pouch. It was the twiggy legs of a dead joey.

|

For all the years I have pulled over to check the pouches of dead mothers and found nothing and then to miss this. I now disgust myself with a lack of sensitive observation.

I know that it was a long day with 700 photos and that towards the end of that day, when I took that photo with the brilliant afternoon light, that I was losing daylight. My batteries were almost flat. My psyche was full of stench and my pc about to give out. I will never know now (because it is too late to make a difference), whether that joey was alive or dead and by the time I drove back, it might be about 700km.

If I did manage to find it, which I would, it would be dead. Anyway, that's a cruel twist of irony. I didn't realise how the ordeal of the dead roos was affecting me, until I saw these two photographs. Is caring enough? I wonder if one can somehow become the subject, while remaining in one's own head?

Notes: About 1500 km of kangaroo roadkill so far, some with faces and others in pieces. It's the end of the dry summer in The Top End. Everything is burning and tinder dry. My favourite part of the year is coming and that is when the first rains of the wet summer when lightning storms come. |

[Above] Hull-6, Marla to Glendambo, The Stuart Hwy, South Australia, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

I crossed the tropic of Capricorn yesterday and it felt very sad once 'the wet' left the air and there was no longer the cry of the pheasant coucal or black cockatoo. I am always sad leaving The Northern Territory. The central western desert, where I am now, is another favourite place. Uluru (Ayres Rock) is one of my mothers and it feels good to know she's out there amongst the gnarly desert oaks, the hot dry wind and the 30,000 year old sand dunes. All is consciousness.

There was a lot of starting and stopping during this kind of photographic documentation. People driving along the highway slowed down to see if I was okay. I pulled over before reaching each carcass. The Stuart Highway is an amazing ampitheatre, all silence and wind. Then suddenly there is this intense intersection that is created. For example, while photographing roadkill, from the north where I was facing, there was a man on a motor bike going at about 70km an hour and behind him a 4WD. Then, coming from the south behind me, a 53 metre long roadtrain. Within a few metres and a few seconds we all appeared to converge on that stretch. The bike rider pulled over to have a chat, the car roared past us heading south and so did the road train heading north. There was a terrific whoosh and crunch with all speed and intensity literally parallel and these several objects at high speed in such a confined area. It's risky, just as it is for all native wildlife. Then, just as suddenly as it had occurred, it was not. Silence, a dead roo, a whirlwind and hawks surfing the end of dry season updraught.

Notes: I lost track of what day it was and when I drove into Alice Springs I was a day out. My own mother was worried about me. I decided that I was going to travel this highway for as long as it took in order to document every one of those roos, or at least those who still had a face. But art all becomes irrelevant at that point or wherever there is suffering in the world. As long as there is a red kangaroo called -O- who holds onto a huge bloody hole in her chest caught in a death mask of agony, or so long as any being suffers in the world unnecessarily. The world is a suffering place, but while we don't have to beat ourselves up about our own powerlessness, we also don't have to increase or add to this situation by causing unnecessary suffering. Instead we can bring God's good work to Earth. I don't know how to say it any other way. We each have the power to transform ourselves and therefore transform the world once we act on its behalf. That is the art of living.

[Left to Right] Roadtrain-47, The Stuart Hwy, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001) Don-3, Marla to Glendambo, The Stuart Hwy, The Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001) Roo-1806, Marla to Glendambo, The Stuart Hwy, South Australia, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001) Don-10, Marla to Glendambo, The Stuart Hwy, The Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

Notes: Remember how I mentioned their claws gripping the highway? Between you and me, I bless each one of them. I can't help it. I just made it into Alice Springs and rang the mother in Sydney. To my shock she started to cry. I got side-tracked out on the highway and was meant to ring her. She panicked. I forgot what day it was. Anyway, I'm in a bit of trouble. I was meant to be in Sydney tomorrow and next week for the brother's wedding. The mother is not very happy about me photographing kangaroo corpses for 5 days on that stretch of road on my own. I haven't felt alone because there are so many corpses in such an immense silence, that I started talking to them. It was spontaneous. It has been an odd experience. Inbetween carrion I have been taking self portraits to see how I've been coping and I noticed today that I have taken on the look of roadkill. But I just have to keep going with these kangaroos. Almost half way there, 2000 photos so far and not one live roo.

I'm exhausted but I knew that I had to do it and I will continue on until it's done. I almost don't care what happens. Everytime I close my eyes I get involuntary flashes, a different image of a dead roo each time. It's an unpleasant flashback. I think it's the shock and repetition, the unconscious processing. It will fade with time. The road itself is always amazing. Western Myall trees and blue salt bush are a prominent feature of the landscape in the desert of South Australia just north of Port Augusta. As we go north trees diminish and make way to stone, scrubby salt bush and spinifex. The colour is red ochre. Off again early tomorrow since I want to make it to Marla roadhouse. That's about 450km just across the Northern Territory border into South Australia.

I drove from Alice Springs (NT) to Marla (SA) taking photographs 1791-1844 = 53. I met Don and his canine companion Bruce. Don works for a company who cleans the roadkill (traffic hazard) off the roads. It's called Masterpath (the Master of the Path). The company is subcontracted to the Dept of Transport and Works. It's role is to remove 'obstructions' to traffic such as rubber, tyres and dead kangaroos etc along a 1400km stretch from Alice Springs to the border, and onto the Lassater Hwy right up to Sandy View which is 30kms from Uluru (Ayres Rock) and then onto the Watarrka (Kings Canyon) Road. Don told me this story of how the wedgetail went through a car windscreen on the Uluru road. As the bird died, its beak latched onto the thigh of the tourist. Don spoke of 'cleaning up' 13 roos and 2 bulls off the bitumen in one run. There were human fatalities with the hitting of bulls, with details published in Alice Springs newspapers. It happened at night. 'There's some real nice looking animals along this stretch of road. It's a shame to see them like that.' He then added, '110km per hour is fast enough.' I almost lost it, when I saw the kangaroo's dead face being dragged along the bitumen.

|

It's been more difficult today in South Australia and the sky a dark grey. The desert loves the rain, is always receptive. Personally, I like the sun. Anyway, there were only 3 roadkill which was a relief. It's the nature of the landscape and nothing to do with the sensibility of the drivers, but somehow it was harder for me, as if all the others are catching up to me, in that space that is created by the absence of trauma. I finally cried, only for a few minutes but it was intense. I have attempted to build an immunity to pain during this project, but it slipped through. It's started raining and I'm in Marla labelling photos for the afternoon in a roadhouse room. I photographed Don cleaning up. It was gruesome as he dragged the kangaroo from the road. I saw its life and face like a gentle friendly dog dragging amongst its innards. It's face started to cave in to its body and go all gooey. It was close enough to love. I had stifled a sob. You see, my own dog Binda, he looks just like that, and besides, my roos are not allowed to move. It might remind me that they were once living and that now they are not living, that they had suffered and I can see that in so many ways. |

[Above] Hull-2, Ti Tree to Alice Springs, The Stuart Hwy, The Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

While my concern and sense of responsibility drives me, I have largely managed to detach myself from feeling anything. From Marla to Glendambo, I took photograph 1845-2107 = 363. I saw 7 crows and an eagle flocking at carcass on road. Does blood replace water 113kms from Coober Pedy? The flies are going crazy. They want fluids. I suppose they'd have liked it more if the roos were half living and I was half dead. We give life and we take life no matter what we do. Even when we don't want this process to occur, it relentlessly continues. This is always a reminder that if we choose to attempt to control our external environment, we are struggling against a force far greater than ourselves. The best we can hope to do is to be viligant in the moment, in 'our attempt' to minimise suffering. The both times I hit an animal, I was given a warning that little birds were darting in and out of the grass. Both times I slowed down, but not enough - because out on those highways we are dealing with distance to be covered, daylight hours to see by and brief time. Nature moves in front of us along that stretch of highway. An infinite amount of intersections are created where animals cross, and we sometimes collide.

There are many fatalities along the Stuart Highway from people hitting animals, particularly cows and kangaroos. I have traveled across Australia a number of times and while I have never hit a cow, kangaroo or another large animal, I had a close call with an emu at Tarcoon in New South Wales. It was dusk in winter. The roads were starting to flood and I got caught out with one headlight dragging from its socket. Again, it was a matter of bad timing or going too far too fast, then there it was. My encounters were caused by speed or driving at night and could have been avoided. Even a body as tiny as a bird or a frog, will haunt me forever. Just because the bodies of these animals were small, their lives were not. Their lifeforce were as purposeful and as relevant as our own. To destroy that essence is to understand one's part in creation and destruction.

When you take the life, either accidentally or on purpose, it doesn't completely die. I believe that its essence somehow lingers at the scene, and it lives on inside you, for you will always carry the act of killing within your consciousness. A family stopped to help me with a blow out a couple of hundred kilometres north of Coober Pedy. The guy pointed to my grill and to where a large dragon fly had been caught. 'Roadkill,' he said.

We can only do what we can do, the countless thousands of insects. It's tough, but it doesn't mean we have to then shrug our shoulders and not do anything. It doesn't mean that we have to give into that, because that kind of attitude only perpetuates the situation of powerlessness and a lack of eros. That would be half-living. I was doing 20km under the speed limit and I hit and killed a bird. I estimated that the car in front of me would have been doing 40kms over and they missed the bird. Pretty soon everyone else was speeding on to Port Augusta, seemingly without a care for the tiny birds and I was a killer confused as to whether to slow down or speed up.

It took many more hours for me to reach the same destination, but at least I had attempted to show some kind of consideration. While I had failed, perhaps the desire to do the right thing would at least count for something. Perhaps not. Certainly not for the bird. The yellow bird only 'wanted' to live its extraordinary life. I don't know what to do. So far I have 2000 photos of roadkill roos. I have only seen two living kangaroos along this entire stretch of road, which happened to be just outside Alice. It seems ridiculous that the only experience we have of native wildlife is the agony of death by roadkill. I photographed snake, falcon and wedgetail eagle - all dead.

PORT AUGUSTA & ONWARDS

|

I drove from Glendambo to Port Augusta for photos 2108-2177 = 69. The flies in South Australia were a lot worse than in the tropics. They swarmed on me and bit my eyes, after being on the decomposing roo, while I was photographing. The last dead kangaroo that I photographed outside Port Augusta (SA) which I call the '5K' kangaroo - that is just 5km from the town centre. The trucks might use the highway during the day. No schedule is worth the loss of life that I've seen. Note 'Teddy' - one of my favourites. The other one is the howling roo called -O-. The agony in the face of -O- is indescribable, can only be described through -O-. A missing chest and claws curled in to hold onto or release all agony. |

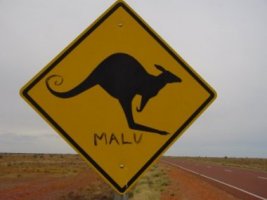

[Above] Malu Roadsign-10, Marla to Glendambo, The Stuart Hwy, South Australia, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

I sometimes worry that I'm going to come outa this trance and think, what the fuck am I doing out here! But it's like I have to do it. I really believe that their story should be told. Notes: I did a few hours this morning on a 80km stretch that I missed on the way in to Alice Springs. The batteries ran out on pc and camera, memory stick full and then sunset, a good time to stop. I will have a rest day tomorrow before heading south.

Notes: During those few days I had 2 flat tyres and a blowout that caused me to run off the road as the wheel left the rim. My brakes failed near Sydney. There was a lot of movement in the grass across New South Wales and when I looked towards it, it was always foxes and crows tearing at the roo carrion. There were dead roos within town limits in NSW! When I left Wilcannia a beautiful dead dog. He was a big black bull dog with a thick blue collar. He was well looked after. Someone had loved him. He was lying there staring at the sky, knocked down on the town bridge. My mother saw the photos of the roos in Sydney and was obviously affected. She looked at me and said, 'that is very morbid and I hope you're not going to dwell on it'. I assured her I wouldn't be. I'm not a masochist. It was done for them. I also avoided hitting at least 6 stumpy tailed lizards crossing the road and many other birds. But I notice another little yellow bird on the road - dead. Many lizards were killed.

[Above] Roo-1651 (Teddy), Ti Tree to Alice Springs, The Stuart Hwy, The Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

On the turn off towards New South Wales, I had get off a freeway at a higher speed with five other vehicles behind me. A stumpy tailed lizard went under my car, but I made sure it would have been in the middle, so it would have been okay. But - I'm not sure as to how fast (left or right) it moved and whether it was hit by the next car or the next one after that, since I was unable to turn back on that section of road. Outside Broken Hill (NSW), the squashed body of a stumpy tailed lizard in the centre of the highway and another one slowly crawling out to investigate. This time I turned back, as I had a thought that the moving lizard might be a partner of the other one. A learner driver was coming. I got there and the learner went straight over the top of the lizard.

Fortunately, it only hissed and was unharmed, so I got my towel and threw it over the top of it and carried it out into the bush. When I lifted the towel off - the lizard was slightly dazed, but this is the amazing thing! His head turned back to the direction of the road and then I knew that he was looking at his mate. I shooed him off into the scrub and he crawled in under some prickly bush. Then, I went and scraped its partner off the road. I never had anything like a spade on me, so I had to use my high heel and there was all stinking lizard blood and guts on my shoe and up my leg, so I was washing that off on the side of the road, because it stank. No more photos. It was heartbreaking. But at least the other one wouldn't keep wandering back out onto the road to investigate.

I avoided 2 head on collisions with trucks, and saw a very close call and another huge accident where a drip was lowered through a cabin window of a truck that had rolled through a barrier and off the highway, with rescue workers cutting the person out. The Great Western Highway used to be the most dangerous road in Australia.

End Notes: I took around 2,500 photos. I actually didn't want the roos to move or be moved, because it made them real again, more real than art. It reminded me that the roo was dead and I wanted so badly for them to be alive because that is what they had wanted. While they were still, I made them live, as if they were sleeping or had slept for too long. But to see the corpse moved by someone else and unmoving, all at the same time, it had been too real for me. I loved that trip and I love that stretch of highway. Even after all the damage is done. We are all the one being. I love them. I thought of them on the way home on the train one morning (in Sydney) - Teddy and -O- and the -5K- kangaroo. I know they would still be out there, more physically gone, but still there.

|

I was happy to be alone and I felt the presence of god. As for the kangaroo, I knew that god was there too, even though she had been dead for 4 days, giving her flesh and bones to the wind and sun, crying green arsed flies on the inland road between Renner Springs and Ti Tree. This God was inescapable. More Endnotes in New South Wales: Just outside of Broken Hill along The Barrier Highway in the late afternoon sun there were shingle backs dead and living. I kicked the blood and guts of the lizard off the road with my shoe. The beady little eye of the living shingle back noted the blood splatter up my shin. I carried it into the scrub. It was waiting by the gush of its mate on the road. The two were now one.

Now it could mourn in the grass alone, unknown and loved by no one. The sun going down. The next stop on the road home is Wilcannia. There was the sleeping snake in the daze of heat, tin shutters with bars across them, music from nowhere, empty streets, council trees, town with the brown river through its slow centre, and more roadkill, this time a bully (bull terrier), still warm. |

[Above] Roo-1604, Ti Tree to Alice Springs, The Stuart Hwy, The Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

In my mind I had to let the dog at Wilcannia go. This was a dawn he would not grace with his presence. No one could touch him. No one in this town could hurt him now. I was too tired to mourn. I remembered the bird back in South Australia. This would be the last short morning for the little golden bird and how it tumbled onto the road behind my car. I saw it in the rear vision mirror. Oh no, oh no,' god I hit her? Then, the orange claw and yellow wing with olive tips cooling in my hand. The quiet sides of the roads offering nothing and offering something, always something that I might take, some damage that I might commit, so much of nothing out here, no comfort or accusation, no idea damage or not, without judgment, emotion. But still there is love.

I began to allow myself to be free of selfhood and self judgement. In this way, perhaps I entered a time before infancy. There was no boundary between myself and the carcasses. I had died. They were living. Where did life begin and end? Certainly not where the flesh begins and where it ends. We were all adrift, particles moving amongst each other, blood and flesh and flies and dust, the life essence broken at last by physicality and fate, the life divided into many other life essences, shocked into splitting by a truck. It was about fragmentation of the life essence and of the selfhood. The coming together and drawing apart of energies, in shifting patterns.

But always the flow continuing beyond division and always its ongoing dissolution and reformation. I had to be conscious of that great highway, as it became treacherous, thundering towards one, energy shattering, bringing the body into agony, creating an abandonment, a departure or shock of residual energy. Powerful destructive collisions. The pain was hard in me. The loss of the glory of the kangaroo, and all she had been, and her final moments of shock, or lingering suffering. But how quick death can be, so that the self leaves before the agony, so that death does not recognise itself, so that it unbecomes. But it's never fast enough. Here was a kangaroo saying '-OOOOOO-' and another blue doe of the northern grasslands, her nose crushed into the road, onto the white line, the border between her physicality and dissolution, her face as purple and crimson seepage, her suffering beyond imagining, so that with empathy we are almost unable to endure the knowledge, her final tragedy. Why do I love her and the gangly backlegs of her joey protruding from the pouch, cold and unmoving?

[Above Left] Roo-60, Pine Creek to Katherine, The Stuart Hwy, The Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001) [Above Right] Roadtrain-7, The Stuart Hwy, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

Moment by moment, with each crossing over, each into the other, no boundaries or borders to hold us back, my back to it - my front to it and visa versa. Which way did I turn? I cannot remember. I barely recognised myself. I thought, what is this habitation of my body? I realised that since childhood I had not known who I was. I had only experienced the idea of selfhood in transient fragments and primarily in relation to external influences, powerful experiences within themselves, yet each connected to the other, by an invisible wall of unknowing. I was not but I belonged, substantial and yet unstable, an ever shifting holographic spectrum, with nothing in between the grid lines. Did these same amnesiac walls slice the reality between myself and her, the kangaroo?

The physicality of the camera assisted in this process of separation, yet it remained impossible to focus on anything but being. It was as if I was left standing on its edge briefly, before being swept away into the flow of everything else around me. These series of photos are about absorption, the roadkill roos into myself and myself into them, until we slowly become, each unto the other, the one long moving journey of moments, and we become limitless each within the other. We become and we become and we become and all knowledge is forsaken, the camera is dropped, the self transcends and conscious creativity ends, becomes preconscious.

This is me, when I am back long enough to take control of the steering wheel, to download photos, shocked at my awareness upon the return. This is my eye, unhindered and limitless. This is who I really am, what I really am, out here in this startling place, where I can be, just be what I am, and where no-one, no human, no time, no ego, no fear, no boundary, no structure, no society, no art, no rules, no judgement, no physicality can hinder me, being who I am. Here I was an eternity, I unbecame. I took photos and then I said; 'Thank you. Bless you, now go to God.' Then as they might have moved on or remained, so I did. It was a prayer for transformation.

It was murmured with love. I was flowing as I now knew that they had been doing and were doing. Perhaps they had done that all along and here I was learning, and here they were teaching me through transition. Only briefly our interlocking psyches, boundaries blurred, voiceless and free as I abandoned whoever and whatever I might be. God is all I wanted to say, god god god god. But there was no need to say it, as everything else had said it, now and forever it was being said and unsaid, being the supreme dialogue of all consciousness, multifaceted, being both un-utterable and uttered. I could have looked at the roadkill roos saying; 'go to god', but really it was they who looked into my being saying, 'Come to God'. Bless them. Always larger. It is hypnotic, glorious.

I can be who I am out here and that is all. I was not there as an artist. I was there as part of the same evolving energy force, a focused and unfocused mental state. Always that camera was light in my hands, always my focus half backwards and half forwards, as if falling in and out of myself, always my consciousness, my self my unself being swept away, so flimsy, so like art to give us a sense of purpose and identity, to give us our humanity and our inhumanity, when all we needed is to be. We do not create art in the outback, the outback creates art in us.

|

This land, what more can one say? We are its art and we belong to it. The animals do not get published, they are the publishers. They are the created and the creators. We stand in awe and reverence. Our eyes are opened to our lack of genius, to our poor and heartfelt imitations, and to a love greater than we have ever known. Even while we attempt to document externals outside our limited perception, the art beyond us is forever making and unmaking, not only itself but us along with it.

We become part of the stitching of the one great fabric, endlessly woven in through time and non-time, like so many energies collapsing and expanding. While alive we always end up self conscious, wondering about truth, objectivity and subjectivity. So what makes us so consistently extraordinary? So fascinating to ourselves? Are the animals outside our skin possessed of this same self-consciousness? Or are they just being? All our religions wait for instructions and miss the signs, while here in these holy lands, all live as God. There is still a place for love on Earth. It's about forgetting who we are. |

[Above] Roo-1252 (-O-), Ti Tree to Alice Springs, The Stuart Hwy, The Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

So here were the roadkill roos still living and there were the kangaroos who were already dead. I observe how the road acts as that crossing, the touch and chance meeting, and how it so represents fate, what was always to be in that moment, and how in that single point of time, in this vast desert outback landscape, how that kangaroo essence was obliterated by that non-essence of that roadtrain. I think of how from the day she or he was born, it would lead from that moment to that moment and from that moment, until the state of being was exhausted of its life force. I think of how the moment had allowed it, both the connection and the separation.

All we had to do as a human or a kangaroo, was to exist or not exist, crossing creek beds, fences and highways, crossing borders and boundaries, suffering and not suffering collisions, nothing else, neither good nor bad, neither conscious nor self-conscious, because this place is in God's realm, and the kangaroo resides in God. We live in the psyche of God. The kangaroo does not go in search of herself. She does not go to war, does not hunger for purpose and truth, does not create art and attempt to claim ownership over art. In this way she does not complicate existence. Yet her essence is undone and redone, while we are artists who can stagnate through fear. We are creators and yet we live apart from the truth even as we seek it. We attempt to speak of it, we are the observers and the observed and we are the great imitators. Whereas out here, what came before this and after this, and what came as connected and separated, fated or not, the kangaroo a vehicle, it is as God is.

If left to my own devices I choose to undo myself. I begin to un-be-me, to-be-eye, to become unconscious, to be inaction, until there is merely presence through a landscape, or landscape through a presence. Where once I was myself, now a breeze, a passing touch, absorption and is absorbed, by the stone, the sun, the sky, the grass, the creek bed, the rock, the road train, the circling eagle, the roadkill roo. When I went into the bush, I lost by one day. I do not know where that one day went, or if it came at all. I had entered the way of universal timelessness, the eternal moment, but I am only conscious of that in retrospect. I was not conscious of it then, in that moment all moments exist and in all moments that moment exists. The way to eternity is through love.

There were many moods and moments experienced along the Stuart Highway photographing the roadkill roos, but the most fabulous moments, where I became eye, art became awareness and there was no fear within, only sensation, that no thought might attach its emotion to, so that no fear might reside within that thought. It was complete dissociation, loss of identity, no recognition, of the place, within an environment, in time, in history, the wind through the grass and leaves became the voice, the sun and its shadows the clock, the water and stone the drawing card, the pain a process, an imagining or a compassion, the dissolution, a release and bliss.

[Above] Roo-677, Renner Springs to Ti Tree, The Stuart Hwy, The Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001)

All in all and reflecting back upon this experience now, it was a moment to moment way into empathy, the becoming without becoming. The recognition of one flesh and psyche. But despite all this un-becoming, this ongoing prayer of abandonment, this multiplicity of being, I could not know of the roadkill roos beyond their presentation or beyond my perception. I could not know of their immense suffering, the courage that was lived in the eternal moment, their lives, their individuality and sensations. I remain in love and in awe of them.

I could not know of their lives, their feelings, behind their thoughts, or their physical destruction. At its most potent my empathy was a state of simple self-awareness, of reaching into the self in order to re-face and re-evaluate my own suffering, in an attempt to not merely project all I am onto them, to know that somewhere along that white line that is the Stuart Highway, to say, that while I am not a roadkill roo, I have experienced the sorrow of existence, therefore I care for their situation, and on the deeper levels, to say, we are the one sorrow, the one expression, the one joy, the one experience and therefore to cherish all, and to know that for one to survive that all must survive. Yet each time that I observed rather than simply being, I was separate, a witness after the event, a wishful thinker, an archeologist, a historian, an artist, rather than an event of being.

Each time I turned in order to make art, to label, to identify, to document, to understand, to seek truth, I chose separation through self and consciousness of the self. I manipulated and edited my unconscious processes into a frozen moment. I stood back and apart from inland Australia, to merely observe, to consume but not to be consumed, but only to record. I watched as life beyond my ego consumes and is itself consumed. The empathy I felt was only existing as fragmentation, a momentary willingness to abandon the self to a selflessness within, a crude identification with all who were taken into life's destruction, its creation, its never-ending, its ways of being and unbeing, its old old story of transformation. I now join this same river flow beyond my imagining.

Aside from the exchanging of places with the self and the other, my ability to truly feel what the roadkill roos had felt, was restricted to the realm of the heart. We can only empathise with them. Despite our love for them, we cannot be them. Yet when we lose ourselves to our art we soar. We are free. It is enough to create art and be created through art. Our empathy is a gift given to us. But it does not lead us to feel the pain or joy of the other. It is merely the first step on the road to compassion, where all is love inescapable. While art searches for truth, it is our way into the greater deeper mystery. However the roadkill roos and the abandonment of the self consciousness that is all too often involved in the creation of art are also our way in. The best we can do is have faith without expectation and become creation without attachment. Only then can we release our empathy like fluttering birds into the great unknowable, into the immense being and unbeing, of all who would continue.

About the Writer Coral Hull

|

Coral is the author of over fifty books of poetry, prose poetry, fiction, artwork and digital photography. Born in 1965 she was raised under disadvantaged circumstances in the working class suburb of Liverpool in Sydney's outer west. Coral became concerned with issues of social justice and spirituality from an early age. She became an ethical vegan and an animal rights advocate who has since spent much of her life working voluntarily on behalf of animals and the environment. Coral Hull's books are available online from Artesian Productions. Coral holds a Doctor of Creative Arts Degree (Creative Writing Major) from the University of Wollongong. Coral Hull is a functional multiple. Her psyche has operated by using multiple streams of consciousness since infancy. Her book Broken Land: 5 Days in Bre 1995 has been broadcast on ABC Radio National twice. An extensive biography, list of publications, interviews, articles and reviews can be found on Coral Hull's website. Coral is The Director of The Thylazine Foundation: Arts, Ethics and Literature. Coral Hull's work is now in the public domain for non-commercial use under the Creative Commons License. |

[Above] Hull-44, Marla to Glendambo, The Stuart Hwy, South Australia, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2001).

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.10 (September, 2004) |