XAVIER HERBERT: AN ESSAY IN COMPLEXITY

By Greg Barns

[Above] Xavier Herbert at Ross River (Photo courtesy of the NT State Library, 1984)

What would Xavier Herbert - one of the most passionate and articulate, if sometimes confused, advocates for Aboriginal Australia, have thought of the Howard government's policy of insisting that in order for them to obtain a petrol bowser, a Western Australian Aboriginal community had to ensure their children's faces and hands were clean?

Herbert - writer, pharmacist, union organiser, and sometime colonial administrator - would have been disgusted and no doubt would have seen in it, another example of European Australia's incapacity to understand and come to terms with the need to address the burning injustice that lies behind so much of the dispossession and spiritual emptiness of Aboriginal-White Australia relations. That issue is of course - the land.

Until there is recognition of the Aboriginal Australians' inalienable sense of connection and sovereignty over land in more than a piecemeal way, then the sort of bizarre and patronising deals that the Howard government has recently imposed, will keep happening. And Aboriginal Australia will be no better off in its quest for genuine equality.

Herbert, although often flawed in his knowledge and description of Aboriginal spiritualism, knew instinctively that for this group of first Australians, the land was not simply a possession for the temporal life. It had a meaning that was fixed inextricably to existence itself.

When he died in Alice Springs on the 10th November 1984 Australia lost on one of its most paradoxically complex but ultimately great individuals. Herbert, without peer as a chronicler of white Australia's injustice to its indigenous peoples, died aged 83. But 20 years later, Herbert has been consigned to the hazy recesses of memory. This is a literary and political wrong in our cultural and historical awareness of the intellectual forces that foretold white Australia's morally anomalous relationship with our indigenous peoples, which must be put right.

[Above Left] Water Birds, Cooinda, The Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2003 [Above Right] Saltwater Crocodile, Adelaide River, The Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 2003)

What makes Herbert so intriguing and heroic is the fact that, unlike the rather sanitised authors of today who have fallen into the clutches of their publishers' marketing departments and therefore say little of any consequence when interviewed, Xavier Herbert had definite views and campaigned relentlessly to bring them to reality.

That Herbert's trajectory was often fraught with near misses, wrong turns and u-turns, does not diminish his extraordinary output and profound influence on Australia at a time when a new form of nationalism based on egalitarianism was emerging.

He was, as his biographer Frances De Groen rightly says, a man who "found himself endlessly fascinating and expected others to do so too". But, as De Groen notes, Herbert was indeed fascinating because of his "incident filled, wandering existence".

Born in Geraldton, Western Australia in 1901, Herbert's mother was an interesting woman to say the least. By the time Xavier was born, she had two other children to different fathers and there is conjecture about the identity of Xavier's father; Herbert lacked a birth certificate.

He grew up in the Western Australian Swan Valley town of Midland Junction, and then Fremantle, and it was in those years that Herbert first witnessed Aboriginal dispossession. He studied pharmacy and in his early 20s left the West to travel to Queensland, the Northern Territory, Sydney, Melbourne, and the Solomon Islands. Eventually the Cairns suburb of Redlynch would become his and his English Jewish wife Sadie's home for many years.

The tragedy of Australia's indigenous and white divide - manifest so recently with riots in Sydney's Redfern - was graphically described by Herbert in Capricornia (first published in 1938) and in letters written while he lived in Darwin during the 1930s. Unlike many in the writing game Herbert was not a passive storyteller- he 'rolled up his sleeves' and made the plight of indigenous Australians his cause celebre.

Living in a period when the 'inferiority' of indigenous Australia was taken as immutable fact - as Herbert described it in Capricornia, indigenous Australians were accorded a status in the Territory below that of a station-owner's horses - the young Herbert challenged the orthodoxy. Capricornia lifted the scab off the indigenous/white conflict.

|

(Herbert was nevertheless eager that the world know of his own personal efforts to assist indigenous Australians - 'You know how I have slaved and suffered and impoverished myself for the cause of aborigines" he wrote to a friend in 1936.)

As Herbert's character Peter Differ pointedly observes in Capricornia the governmental system of 'protection' of indigenous Australians was designed to ensure 'humility'.

And while white Australia in the 1930s applauded the efforts of Christian missionaries to make 'good God fearing' people out of indigenous peoples, Herbert mercilessly and accurately ridiculed that effort in Capricornia. He noted in a letter to his friend Arthur Dibley, on 17 October 1936, "the missions have failed to do more than upset tribal discipline".

The hero of Capricornia is Norman - son of a white man and a black woman. The 'half-caste', as people such as Norman were then known, were, as De Groen notes, perceived by white Australia as a threat to its conquest of the land. This group of people might 'revitalise' what was alleged to be a dying aboriginal civilization.

Herbert identified with those born from indigenous and white parentage. He claimed that only if he 'infused' his blood with that of indigenous Australians would he be able to 'claim the right to live in this land'. |

[Above] Front Cover of Capricornia by Xavier Herbert (Front cover: detail from Russell Drysdale, The Outstation, 1965)

As a white Australian we are simply invaders, according to Herbert. He founded, in 1936, a 'Euroaustralian League' for people of white and indigenous ancestry - "Fantastic, is it not, to teach people to feel proud of Aboriginal blood?" he wrote to Dibley. It was a wacky but perhaps understandable inversion of the "racial purity" theories running around Europe and the British Empire at the time.

On a practical level, Herbert made himself unpopular with the local administrators of the NT, ('tin-pot rajahs' as he called them) in his two sojourns there in the late 1920s and mid 1930s. In October 1935 Herbert was appointed the Superintendent of the Kahlin Aboriginal Compound in Darwin. His record there was not unblemished - far from it. He was accused of taking a stick-whip to an Aboriginal 'halfcaste' girl and confessed to assaulting a male indigenous person. But Herbert's achievements on behalf of those indigenous peoples 'imprisoned' in the Compound were tangible and definitely set him apart from the Territory's racist administrators of his epoch.

As De Groen, no shrinking violet when it comes to criticism of Herbert's ego and capacity for exaggeration and excess, notes, with Herbert running the compound, toilets were erected, a windmill built, a school for 'halfcaste' children established, and the Compound's corrugated iron huts repaired. De Groen summarises Herbert's efforts, "Aborigines who knew Herbert at this time, appreciated his efforts on their behalf, particularly his attempts to encourage pride in their cultural heritage. In befriending many of his charges and treating them as fellow human beings, Herbert represented a threat to Darwin's prevailing white supremacism."

Herbert's memorably bleak description of the food at the compound was widely quoted in the 1997 Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission's report on the Stolen Generation: "The porridge, cooked the day before, already was sour and roped from the mould in it, and when doused with the thin milk, gave up the corpses of weevils by the score. The bread was even worse, stringy grey wrapped about congealed glue, the whole cased in charcoal."

Yet Herbert's legacy remains obscured by current literary fashions. One of the most frequent writers on the Northern Territory and the Top End of Australia generally in recent times has been The Australian's Nicolas Rothwell, who rarely if ever cited Herbert as an inspiration.

Rothwell's writing misses a beat or two as a consequence of this omission. His colleagues who journey from the south to wonder at the mysteries of Australia's vast north seem similarly oblivious to the power of Herbert's prose and insights into a land that seemingly teems with spiritual mystery.

|

Herbert's novel Capricornia, (and Poor Fellow, My Country, for that matter) an epic work that spans 50 years of the NT's formative years of white imposition on indigenous culture, should be compulsory reading for any writer in that part of the world. It's a promethean oeuvre, rich in irony. Its humour is quirky and vicious. It is a novel that explores the complexity of the harsh, beautiful and unrelenting landscape of climate of the Northern Territory. Herbert writes of the fictional cattle station Red Ochre, "At times he loved it best in the Wet Season - when the creeks were running and the swamps were full - when the multi-coloured schisty rocks split golden waterfalls - when the scarlet plains were under water, green with wild rice ..."

But above all, it was the first novel of note that exposed white Australia's indifference to Aboriginal people. Right through the work are heart rending descriptions of the institutional racism, ignorance and prejudice that existed in those parts of Australia where Europeans and Whites co-existed. |

[Above] Xavier Herbert (Photo by Jacqueline Mitelman, 1988)

Early on in Capricornia, the character Peter Differ describes a conversation he has with a kindergarten teacher in Darwin.

"She led off by telling me not to get the false notions into my head about her pupils' unhappy lot. With a smile she told me there were Only Niggers."

Poor Fellow My Country - all 1463 pages of it - was Herbert's finest achievement, of only because of the length and breadth of the novel. It is almost biblical in parts - Herbert as the messiah.

This is a novel that contemplates an Australian salvation or the possibility of an eternal damnation. The grandiose visions that Herbert conjured in his musings and writings are translated and writ large in this powerful novel that ebbs and flows like Mahler's gigantic 8th symphony - the 'Symphony of a Thousand'.

(As an aside, Gustav Mahler and Xavier Herbert make for an intriguing comparison - both needy of praise and a sense of a larger self, both transfixed by powerful women, and both struggling with visions of an apocalyptic ending to the world they viewed.)

Like Capricornia, Herbert wove themes around Australia's north, Aboriginal mythology and the avarice and bitterness of Europeans seeking to tame the untameable.

|

When it was published in 1975, Poor Fellow My Country hit a harmonious note with many Australians. The Whitlam government's championing of Australian identity through culture and its preparedness to accord Aboriginal Australia land justice meant that despite the almost impossible length of Herbert's novel, it was generally well received.

The opening paragraph of Poor Fellow My Country describes Herbert himself in many senses. Conscious as he was of his own confused parentage, Herbert identified with what was then described as being 'a half-caste.'

"The small boy was aboriginal - distinctly so by cast of countenance, while yet so lightly coloured as to pass for any light-skinned breed, even tanned Caucasian. His skin was cream-caramel, with a hair-sheen of gold. There was also a glint of gold in his tow-tawny mop of curls. Then his eyes were grey - with a curious intensity of expression probably due to their being cavernous Australoid orbits where one would expect to see dark glinting as of shaded water. His nose, fleshed and curved in the mould of his savage ancestry, at the same time was given just enough of the beakiness of the other side to make it a thing of perfection. Likewise his lips. Surely a beautiful creature to any eye by the most prejudiced in the matter of race…Yet most people, at least of this remote northern part of the Australian continent, would dismiss him as just a boong." |

[Above] Front Cover of Poor Fellow My Country by Xavier Herbert (Angus & Roberston Publishers, year unknown)

Herbert is describing the character that looms large - in an almost Wagnerian sense - over Poor Fellow My Country, Prindy. Prindy, who along with the Australian nationalist of the story, Jeremy De Lacy, is an idealised representation of Herbert.

And Herbert is also able to weave into the novel that other dispossessed and 'chosen people' - the Jewish people.

Sarah Rifkah - clearly a representation of his wife Sadie - serves two primary symbolic purposes for Herbert. She nourishes Prindy, sexually and emotionally, and she is a superior being because of her Jewishness.

In a letter written to Sadie on 11 March 1968, Herbert lavishes Rifkah with this praise.

"She was born to be the mother of the most powerful breed of people in the world & hence the most tragic, since their power is limited by the hatred of those who can't emulate it."

Herbert's admiration and self-identification with Jewish people saw him changing his will in 1975 to gift his property at Redlynch to the United Israel Fund - altering his previous wish to gift it to Aboriginal people.

In Jewish people he saw a 'superior race'. His complex relationship with Sadie may have contributed to this belief. Despite his disloyalty to her, his cruelty and neglect, he could also be effusive in his warmth to her and there is little doubt he needed her and relied on her as a child does his or her mother.

But while Herbert's writings exposed Aboriginal dispossession, he was not always a great admirer of traditional Aboriginal culture - thus the European/Black fusion appealed as the redeeming outcome.

This juxtaposition between compassion and gross insensitivity was borne out in a piece Herbert penned for The Bulletin magazine in March 1962. In this article, which understandably generated considerable controversy and condemnation, Herbert described Aborigines as 'degenerate' and 'filthy' and justified the removal of five white children from a Northern Territory school by their parents, because Aboriginal children were enrolled.

But at the time of writing this inflammatory article Herbert and his fellow Cairns 'arts identity' Percy Tresize were traversing Far North Queensland and finding Aboriginal rock art.

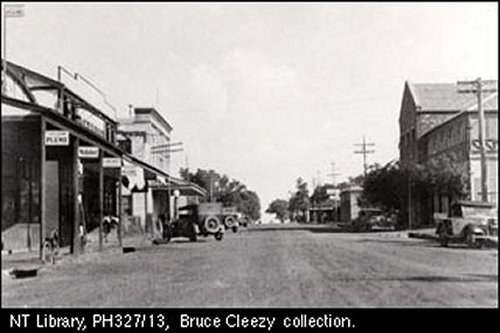

[Above] Darwin 1930s - where Herbert hung out, The Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo courtesy of the NT State Library, 1930s)

In addition to this contradictory attitude, Herbert's retelling of Aboriginal rituals, Dreamtime legends and mythologies in Poor Fellow My Country, is, despite appearances to the contrary, dubious.

The descriptions of the Kunapipi fertility ceremonies - common across Northern Australian and stemming from the Roper River where the Kunapipi mother rose from the sea to create humans and institute human rituals, as De Groen describes it - in the novel are inaccurate.

As De Groen records, in some parts of northern Australia the 'fertility mother and rainbow serpent' are inextricably linked with the Kunapipi and therefore one has to be careful not to compartmentalise the sexes in interpreting the rituals associated with the Kunapipi.

But Herbert does just this. In Poor Fellow My Country, Herbert, De Groen notes, 'minimised regional differences in tribal cultures to preserve a "unity" in Northern Australian Aboriginal experience centred on the "old woman" cult. He also allegorised Kunapipi mythology to express a fear of the feminine - something that it is clearly not faithful to the Aboriginal understanding of Kunapipi.

But for all its faults, Poor Fellow My Country, is probably Australia's only 'spiritual' novel. It is not Tolstoy's War and Peace, as Herbert hoped it would be, but in its exploration of the conflicts that have riven this country apart over the 20th century, it is unsurpassed.

In its exploration of the Dreamtime and the complex rhythms that lie deep in Australia's physical self, Poor Fellow My Country will probably never be equalled, of only because in this era of 'reality TV' and an Australian literary climate that seems to celebrate the obscure and the ordinary for the sake of it, it is unlikely that anyone would seek to continue the unique Herbert schema.

* * * *

Almost fifty years after Herbert's travails in the Northern Territory he returned to give evidence in a major land rights case - the Finniss River Land Claim. As De Groen describes it, Herbert's evidence to the court in Darwin on 25 August 1980, "was helpful in establishing the presence of the Warai and Kungarakan peoples on parts of the land…and in illustrating the way officialdom had inhibited Aborigines from maintaining their traditional cultural links with 'country' by breaking up families and forcibly removing them into government institutions".

Despite ill-health, in 1983, shortly after the election of the Hawke government, Herbert travelled across northern Western Australia and the Northern Territory to look at Aboriginal industry. He met with Stephen Hawke, the Prime Minister's son who had worked closely with Aboriginal people in Western Australia for some years, and prominent Aboriginal activist, Pat Dodson.

[Above] Ubirr Rock Floodplains, Kakadu, The Northern Territory, Australia. (Photo Collage by Coral Hull, 2001)

Herbert, according to De Groen, was disgusted and enraged by the conditions he saw on his trip. He fulminated against the 'constitutional lie' of terra nullius - ten years before the High Court swept it away in Mabo - and reversed his decision to hand his property at Redlynch to the United Israel Fund, instead giving it to a local group of Aboriginal people.

Xavier Herbert's burning desire for justice for aboriginal people was often clouded by his own ambition, scheming, grandiose visions and his anti-Asian rhetoric. But the genuineness of that commitment and the ever-present acknowledgement that white Australians will always be the invaders of this ancient land never wavered. In an age when both the Liberal and Labor Party, egged on by elements of the media, refuse to deal with the threshold question of a formal apology for the horrific wrongs described in Capricornia and in other testimony, it's timely to remember that once upon a time one Australian placed it before us and pricked our collective conscience.

Herbert's observations and insights into European Australia's injustices to Indigenous Australia are not just historic - they are directly relevant to Australia's sense of identity today.

Xavier Herbert's cultural and political legacy deserves constant recognition and more than that in today's Australia. Herbert should be accorded rightful recognition as one of Australia's genuine cultural lions. As is the case with most that fall into that category, there is contradiction, an underbelly that is often unpleasant, and a polemical disposition. Be that as it may, do not let it obscure the genuine greatness of this confused, complicated but visionary writer and sometime activist.

Bibliography:

Xavier Herbert (2002) Capricornia, (Angus & Robertson)

Xavier Herbert (1975) Poor Fellow My Country (Collins).

Frances De Groen (1998) Xavier Herbert (UQP)

Frances De Groen & Laurie Hergenhan (eds) (2002) Xavier Herbert: Letters (UQP)

About the Writer Greg Barns

|

Greg Barns is a Hobart based writer. He is a lawyer and former political adviser to a number of Liberal leaders and ministers but left the Liberal Party in 2002 because of its policies towards asylum seekers. Greg is the author of What's wrong with the Liberal Party? (Cambridge UP, 2003) and Selling the Australian Government: Politics and Propaganda from Whitlam to Howard (UNSW Press, 2005). Greg writes a weekly column for the Hobart Mercury, a fortnightly column for the South China Morning Post and also writes regularly for The Age, The Australian, the Herald-Sun, the Courier-Mail and the Sydney Morning Herald. His work has also been published in the Guardian, The Independent, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Sacramento Bee, the Mail & Guardian, the Globe and Mail, the Daily Star and the Vancouver Sun. Greg has also written on Xavier Herbert for onlineopinion.com.au and for Eureka Street. |

[Above] Photo of Greg Barns by The Hobart Mercury, 2001.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.10 (September, 2004) |