AUSTRALIAN POET EMMA LEW

IN CONVERSATION WITH CORAL HULL

By Emma Lew and Coral Hull

[Above] Coral Hull and Emma Lew receive their PhDs. Not! (Unknown photographer, 1999).

CORAL: As writers we are often asked when we first started to write, so I might start by answering that question. When I was thirteen years old, lying on my pink tasselled bedspread on hot humid afternoons in the western suburbs of Sydney, a few precious books quietly borrowed from the Casula High School library began to open up worlds that the adults around me seemed to be closing down. Books were my perfect companions, scriptures of the wide world read in safety. They gave me the permission to explore, and cautionary tales, but, most importantly, the depth of life, the tragedy and beauty of everyday existence. From these initial texts my mind began to create its billion pictures. Then, after hearing my father's drunken recitation of Banjo Patterson's 'The Man From Snowy River' whilst in the garage setting his fishing lines. I even dug up a few dusty Enid Blyton's and Anne of Green Gables from the covered shelves. I found my way into the Australian landscape through Patterson, then Lawson. If they hadn't been so popular, I might never have found them.

It is here in these books that I grew into something beyond my immediate environment. The characters within the books, and their anonymous writers, became my guides. Before books, there was radio, television, and the movies. Alongside personal experience, all these works of art were intrinsic to the formulation of my earliest ideas. Meanwhile, down in the dank backyard shed, dad had stored away his favourite print, with a few old brushes in a plastic bag. It was of a young boy out on an American prairie munching into an apple. The half-wild boy held a book in his hand, and in the sky above him were his thoughts, a scene from a cheap western. This was my father's way of preserving his imagination, the great teacher of childhood. Even now astronomers will say that when approaching astrophysics and cosmology the only limit is the human imagination. I wrote my first poem at thirteen about a rainforest. I wanted to be a 'writer' from that point on. It was something I could do, when I thought I couldn't do anything.

I then spent years writing very bad poetry and prose in isolation. By the time I got to the University of Wollongong, to enrol in Ron Pretty's creative writing course, I had written a few novels, books of short stories and hundreds of poems. I was basically illiterate so they all had to be trashed. I think I was allowed into the course through Ron's sense of my 'absolute enthusiasm' for writing. I really began to write properly a decade after this first poem, after obtaining my Bachelor of Creative Arts degree and spending a year in conceptual art school in South Australia. An intense voyage into the visual arts and a severe nervous breakdown in my early twenties were my final triggers into being 'able' to write. The 'slashes' that were to become part of my technique emerged overnight and I wrote my first book, In The Dog Box of Summer (Penguin Books) from there.

Emma, I'm going to start by firstly asking you what brought you to creative writing, in this case poetry? Tell me all about your first poem and the idea that it might become part of your book of poetry, The Wild Reply.

EMMA: I'd wanted to 'write' for a long time; in what form, I didn't know - something along the lines of editing, speech-writing, copywriting ... Poetry was an exalted art, requiring a depth of learning and intelligence, insight and feeling I knew I lacked. Didn't even think about it. But about a month before my mother died, over six years ago now, I just suddenly started writing poems. Preparing myself in some way, perhaps. Then, after, it was almost as if the poems could do part of the grieving, letting me stay numb. Fortunately, I began Alan Wearne's poetry classes around the same time, and he bore with all the crap I was coming out with, teaching discernment and control, then later putting me on to John Forbes, an inspirational tutor also, who'd constantly amaze me with his authority, his incredibly fast and intelligent eye. He'd say 'Yes' or 'No' to a poem, and he'd be spot-on. He told me I'd better start reading, and made me borrow Ted Berrigan's So Going Around Cities, which just left me breathless, so daunted I wrote nothing for over a month. I'd never really read poetry before - beyond a bit of Auden and Eliot, some Plath at uni . . .

Reading's been my teacher since Wearne and Forbes. And John Anderson. It's difficult to express what exactly it was that John gave me. We shared a sensibility for language and infused each other, I think, with our respective tastes and perspectives and methods. We had this implicit grasp of each other's 'poetic', and it got to the point where we felt that we could each write for the other. He introduced me to poets like Bonnefoy and Ponge, Geoffrey Hill, Georg Trakl, Paul Celan, Ungaretti and Holderlin, and so many more. And he made me re-read Emily Dickinson.

I didn't consider myself a poet until people started to call me one. Then I did. It sounds so abject, but I needed to have the title conferred on me; it would have been presumptuous to claim it for myself. I never thought I should try to publish a book of poems until people started to suggest I might. And then I did. The responses I was getting made me dare to become ambitious. It's just gone on from there.

Coral, let's talk about the way we write, and why we write the way we write. For instance, when did you start using slashes, and why?

CORAL: I initially used slashes as a way of controlling line break and rhythm, and as a way of avoiding being consciously concerned about either of these things. I've always been more interested in concept over construction, philosophy over technique. This has to do with my way of relating to the physical world and identifying myself within that world. In my life I have been a minimalist and eventually gave up visual arts in preference to writing, simply due to its physicality. In the end the mere materials involved such as objects, colour, pattern, and technique were creating a sickness or confusion in me. For me writing is an art form based on idea. The absence or reduction of 'the physical' allows me to function more effectively. I would rather be a singer than a sculptor, for example. So in fact these 'slashes', chosen virtually overnight, were a way of disregarding poetic construction.

Once I had used slashes, the writing came in uncontrollable waves of ideas, that had been locked inside or ill-expressed on previous occasions. The use of slashes gave me the ability to express myself after years of struggling for literacy. Of course, once this occurred, the slashes became their own technique. The manipulation of the slashes, in relation to the text that they divided, allowed me to compress ideas into tiny boxes. For me it was like pushing a jack-in-the-box back into a contained form. I was also insecure about being exposed in some way, and so hid within the boxes. I believe this technique, and the fear involved at the time, gave my work its intensity. In comparison any attempts at prose seemed watery. I'm talking about over eight years ago now, when I was twenty-five. The use of these slashes lasted for around four books out of the thirteen I have now written. After Bestiary (my fifth book) I dropped slashes in preference for commas and traditional verse, and wrote Broken Land (Five Islands Press) in a completely conventional fashion. I have now dropped the use of poetic form altogether, in preference for a very dense style of experimental prose.

Now I want to ask about your use of 'appropriation' and other people's lines. I remember when we travelled together out to Broken Hill, New South Wales, a couple of years ago, that you were taking down lines from books that interested you. It seemed to be a specialised collection of ideas, catering for whatever you needed to express at the time. For example, if you went through the same book a few months later, I would assume that you would collect a completely different set of lines. You once mentioned to me that you believed that this was the only way you could write. So, tell me, how does the use of other people's lines work so well for you, and why do you choose this technique over simply writing your own down?

EMMA: It's still the only way I can write, or at least write poems that seem deep enough, knowing enough. I'm still filling exercise books with lines and words I read or hear, most of which I never get to use. There's two parts to this method: skimming texts - as many and as diffuse as possible - for rhythms, textures, truncations, etc.; then cobbling the bits into coherent pieces, staying concerned mainly with the flow and integrity of the language, and hopefully thereby letting sense, or 'meaning', arise of itself. I think that what suits me about this method is how it gives me the illusion that the poems assemble themselves. It sounds so simple and shonky, but it isn't; it's really painful. I'm amazed and terrified sometimes by the huge strangeness and precariousness of making a poem; how dicey the whole process is, how hard. Somehow I don't seem able to bring my self, my conscious self, to the poem: I'll only mar it, make it slight. You describe how the containment of the slashes gave you freedom: I guess I do feel trapped by my method of working, but at least it lets me speak, if only on its terms, and themes and preoccupations emerge which I'd otherwise never have access to. I show myself through the poems that I do know more than I know, feel more than I do feel. And while it's scary, never being quite in control of the poem, it's exciting too - the experience of pulling off some wicked sleight of hand . . . It's like a magic that's always threatening to vanish.

CORAL: It's like we are both using these methods to dig up and release the form within, working down through the soft grey dust, at our own creative archaeological dig sites. I'd like to talk briefly about another technique I use. I am presently working on a book of narration of tropical landscape. I've chosen this area for personal reasons as yet still unknown to me, and because it is a unique and neglected part of Australia, often absent in Australian poetry. Today a flock of black cockatoos were feeding in a stand of Casuarina trees on Nightcliff Beach. The sight of large birds' gliding through the needles that feel like gentle green rain, and their long harsh cries, took me by surprise. I felt captured. It was similar to falling in love, the sensation was reduced to the scene directly before me. Everything else including my own self-awareness became vague and out of focus. The situation was mystical. It was as though the land whispered through me, in a kind of internal dictation. I'm not sure whether I said the lines out loud or not. I was only certain of the scene itself, which I was a part of, but was not aware of myself as part of it.

This is often how I begin to write in a landscape where words are absent. This interpretation is very individualistic and subjective. Afterwards I go home and type the lines into my computer. So, like your lines extracted from books, these lines 'seemingly' extracted from landscape, will lead me into a greater understanding of the situation. It's as though we have to excavate ourselves from somewhere else, do you think? Like we are somehow disembodied in order to search out what it is we really want to say. I wonder why this is? Once back at the computer the work is a mixture of memory, interpretation and invention. This is where I become aware of an audience. During the experience itself awareness is largely absent. A little further down the beach I looked back at the black specs sitting in the Casuarina trees and recognised myself as a specks. Self-consciousness had returned. I felt stunned as if the effects of a drug had worn off. Your work also seems to be mysterious, undiscovered, which is part of its attraction for me. I think that this exploration or unknowing, no matter how we go about it, is an essential part of creative development.

EMMA: There's a line by Pessoa that goes, "Don't seek, don't trust, for all is mystery". Yes. The mystery is integral to creating. There's a thrill, for me at least, in the unknowing. To write poems sometimes feels like receiving stolen goods and sensing that it's wisest not to question where they come from. If I can write a poem, that's great; but I shouldn't try to analyse how or why. Something might be disturbed. I might lose the knack, and I'm always fearing that - it feels so tenuous.

So poetry is for both of us excavation . . . Where poetry comes from, what it is, what a poem actually is - that's the mystery . . . Something intangible made palpable. Something evanescent pinned down. A poem that works is incontrovertible, unassailable. Whole and hard, like a stone. It coheres, it convinces. It can suck you into its own screwy logic. It can resonate like the purest music. And it may be formed of language so plain or fussy or abstruse, but it works because that language is honed and apt; because the words have shed their mundane effects and can divulge a deeper sense. The word "offering" often comes when I try to work out what poetry is for me. I've felt poetry's power to console in dire times, how a poem can strengthen you when you are frail; speak, when you need to hear it, of the darker, unfathomed realities, like death and pain. But poetry won't explain things to us. Rather, it adumbrates, intimates. It celebrates the momentous and the mundane, accompanies us through what must be endured. It seems to know. Know, though not in a way that's declamatory or final, but subtle and allusive, letting the reader take from it what has relevance and resonance. I think that for me this is the eeriest, loveliest aspect of writing poems - to be ignorant and inexperienced in so many areas, and yet find sometimes that my writing has struck chords in a reader; has said something to them.

Coral, I want to know what a poem is to you, what its purpose is, what you want it to do - to yourself, to your readers.

CORAL: It's a simple matter of empowerment. I'm faced with a huge and bewildering existence to which there seems no sense, no meaning, no purpose. I sit down on a northern Australian beach with a stick and start scratching my thoughts in the sand. A tide comes in and out they go, into the mouth of a crocodile. It sounds like a desperate and pointless act, but there's a chance that it will be read by someone before the waves abolish it. The important thing is that I bothered to write it at all. Otherwise, I'd just spend all my time praying or daydreaming. It's an elemental and philosophical act for me. If I wasn't a writer I'd be an astrophysicist, a mystic, a secret agent or a para-psychologist.

Writing is like flying a kite of dreams through the worst storms, it's courageous and says: keep going. It's a disembodied intention, yet once expressed it's my message bottle thrown into the ocean from a barren shoreline. Poems are my connection with other human beings, hopefully on those deeper levels. When they are good, poems are an instruction on life. I read them to learn about things, the power that is all about me. I like to read poetry books in one sitting, from start to finish, thoroughly digest them so that their essence enters my body. Once satisfied I will then rid myself of the physicality of books as objects by donating them to libraries, so that others can feed. Some books, like John Tranter's At The Florida (UQP) and The Forest Set Out Like The Night (Black Pepper) by John Anderson I read twice. Poetry is food for the psyche, and when it's good, I can eat without throwing up.

Each completed book is a spiritual lesson. As for my own work, I am very complimented when my work inspires someone else to act, whether this is in a creative or an ethical way, or even when they react emotionally, when they laugh or are threatened. In some ways it's like a child in me seeking attention. Look what I've done! I've written a sad story on the edge of the shoreline about an old salty (salt water crocodile) that nobody cared about. Someone might read that story and love that reptile, if even momentarily, they might smile at a sad sea. This is the political or spiritual act of writing, that is when its intention is to better the existence of another sentient being. This is why I'd prefer that my work reach as many people as possible. Isolation is only part of the creative process. It's not enough to just exist for me. I want to write it down and then have something done about it.

EMMA: Recently Jordie Albiston said she found my poems had strong masculine tones. I'll admit that this was gratifying. And I was trying to write like a man, somehow; to disavow my womanhood, or invoke it only in order to send it up. Even to write sexless poems. For me, men's poetry seemed to have real assurance and stridency; abandon, yet precision. Things I strove for. So much of women's poetry, on the other hand, seemed embarrassingly interior, indulgent, unadventurous. Emily Dickinson, whom I see as hugely important, I felt wrote like a man. She gave her work a wonderful contained passion and explosiveness. I think my distaste for female poetry, my need to dismiss it out of hand, is fading. Probably something to do with feelings of rivalry and inadequacy which I'm better able to surmount these days. And I'm reading such interesting and inspiring contemporary women poets at the moment - Jorie Graham, Louise Gluck, Mebh McGuckian. Each decidedly womanly. Each writing with great tautness, clarity, and mystery. How about you: do you see men's and women's poetry as essentially different? How would you characterise them? Do you think your work is strongly feminine? What does it mean to you to be a woman writing today?

CORAL: I think that our shying away from women's work that you mention above is simply another symptom of patriarchy. I initially thought because I wrote about trucks, dogs, and drunks that I may be writing like a man. On a basic level though, take a look at the difference between the work of Les Murray and Judith Wright. I think you will see a good example of masculine and feminine approaches to landscape interpretation, both dynamic in their own ways. Where I really notice the absence of 'a woman's story' is at the movies. I can usually pick a movie by the way the first female character appears. If she's a sex object from the outset, the movie is male-orientated. I don't think there's necessarily more depth to women's flicks, (I love action movies), it's just that there's such an absence of our story or at least some other story, that I'm hungry for more, hence more appreciative.

It's kind of like the difference between a Canadian and an American movie. You see a great movie, and at the end you think, 'Geeze, that was good for Hollywood'. Then when the subtitles are playing, you see that it was made in Canada. It's like taking a deep drink from meltwaters in British Columbia after Adelaide tap water. I've come to the conclusion that no-one's telling my story, so I'm going to tell it. Incidentally, the working-class issue for me has been just as powerful as the feminist. I spent many years surrounded by the middle-class art world, unable to articulate why I was feeling so isolated. If the working-class were courageous enough to come to terms with their situation, there would be a cultural revolution. Ultimately, I think we should stop thinking about ourselves as gender-specific, unless we are pushing feminist politics, and just keep writing our own stories, whether interpretive or imaginative. Hence, my reluctance to explore this topic in much detail.

So Emma, what would you be if you weren't a writer? Do you think that as writers we need to live sheltered and isolated lives or do we need life experience? How is your own experience coming to live in your work?

EMMA: If I wasn't a writer now, I'd be a cranky secretary, mouldering in an office somewhere, too hapless to struggle out of the rut, too scared of my limitations to seek more for myself. It's a total fluke that I stumbled into poetry, having dabbled in so many areas over the years, never persevering. I feel that my life is pretty sheltered and isolated. Is experience fuel for the poems? Yeah, I guess. In a way, they're an unconscious working through of experience, a way of coping and transcending. So much of my stuff is imagined, vicarious; yet somehow it all kind of ravels up with what I'm going through at the time of writing. I showed something to Gig Ryan which to me was just a love poem - two people moving around together in the 19th century maybe. She asked if it was an elegy. 'No!' I was adamant. Then later it dawned on me how personal that piece was, how clearly an elegy - all the details, the clues it contained. I was really shocked by that, by how much I was expressing or giving away quite unawares. But at the same time I don't think I care what the poems reveal. They're only poems: nothing's true and everything's true. What matters is that they work. And I love to seem deep and wordly!

That's something else I wanted to ask. . . We're very different, you and I, in what we want our poetry to do for us. In my case, OK sure, the point of writing poems is to try to participate in and contribute to poetry's evolution, and to extend the possibilities it offers, so far as I can. But I've got mercenary ends too. I want to impress people. I want the poems to get me attention and recognition. I want a place. How about you, what do you want ultimately out of all of this? What do you want poetry to get for you?

CORAL: For me the act of writing poetry has been a great challenge, performed largely in isolation and without support. You want 'a place' and I want life on earth to be like heaven. I'd rather be a superhero or an activist than a poet. But I keep hearing John Kinsella say 'direct action with words'. And then Anthony Lawrence takes me aside and says he's worried about me going to all those slaughterhouses. He was right, it damaged me more, but those poor condemned animals are there right now! I used to spring out of bed in the morning and work myself into exhaustion each day to stop myself from seeing them, all the dark little faces, pleading and disappointed. I can barely live with the knowledge. Writing poetry is never going to get me what I really want, Emma. It is never going to allow me to alleviate suffering in this world, to be a god in any way. It's such a small creation, but so intense, full of insight and yes, it's often beautiful. More like a raindrop than a dictatorship, at least it allows us to dream, to continue. I think being an outsider to the literary scene contributes to the various topics of my work. I've read seven books of poetry in the past fortnight: John Kinsella, Mark Doty, Gig Ryan, Dorothy Porter, Philip Levine, Francis Ponge and Ian McBryde. But presently there may be long periods of time where I prefer to be with my two dogs, or wander off somewhere with the NT Field Naturalists Club, and involve myself in other pursuits, with people who don't know what I do. I have to forget that I am a writer in order to write. Most importantly I have to forget a scene, a clique or an establishment. As much as part of me wants to belong, I never fully make it in. The Australian poetry scene is dynamic, but the infighting is still rampant. It's too small for me.

About the Poet Emma Lew

|

Emma Lew was born in Melbourne in 1962. She completed an Arts degree at Melbourne University in 1986, and worked as a deckhand, shop assistant, proof reader, receptionist and clerical assistant. She began writing poems in 1993, and her first collection, The Wild Reply (Black Pepper, 1997), was joint-winner of The Age Poetry Book of the Year award, winner of the Mary Gilmore prize, and short-listed for the NSW Premier's Literary Prize. Her work has appeared in journals in Australia (including HEAT, Meanjin, Island, Overland and Southerly), and overseas (including PN Review, Wormwood Review, Hanging Loose, Landfall and Prism International). In addition, her poems have been included in anthologies, among them New Poetries II (Carcanet, 1999) and Australian Verse - An Oxford Anthology (Oxford, 1998). A chapbook of new poems will be brought out by Potes and Poets Press in the USA in late 2000. |

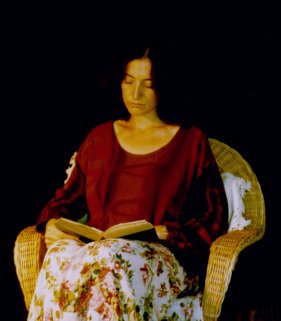

[Above] Photo of Emma Lew by Jenni Mitchell, 1998.

About the Writer Coral Hull

|

Coral Hull was born in Paddington, New South Wales, Australia in 1965. She spent her childhood in Liverpool, on the outer western suburbs of Sydney. Coral is a full-time writer specialising in poetry, experimental prose fiction, scripts and literary articles. Her work has been published extensively in literary magazines in the U.S.A., Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom. She is also the Editor of The Book of Modern Australian Animal Poems, an anthology of Australian poets writing about animals from 1900-1999. Her published books are: In The Dog Box Of Summer in Hot Collation, Penguin Books Australia, 1995, William's Mongrels in The Wild Life, Penguin Books Australia, 1996, Broken Land, Five Islands Press, 1997 and How Do Detectives Make Love?, Penguin Books Australia, 1998. Coral is an animal rights advocate and the Editor of Thylazine, an online literary magazine featuring articles, interviews, photographs and the recent work of Australian artists and writers working in the areas of landscape and animals. She completed a Bachelor of Creative Arts Degree (Creative Writing Major) at the University of Wollongong in 1987, a Master of Arts Degree at Deakin University in 1994, and a Doctor of Creative Arts Degree (Creative Writing Major) at the University of Wollongong in 1998. |

[Above] Photo of Coral Hull by Cliff Hull, 1999.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.1 (March, 2000) |