CHURCHILL MANITOBA: WRITING IN THE SUB-ARCTIC

By Coral Hull

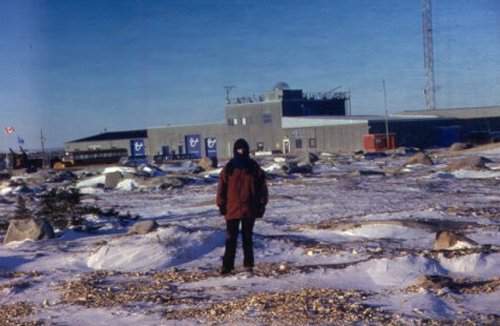

[Above] Coral Hull outside the Churchill Northern Studies Centre, Churchill, Manitoba, Canada. (photographer unknown, 1998)

I chose to go to Churchill, 'the polar bear capital of the world,' in northern Manitoba, Canada, after seeing a special on Australian TV several years ago. Churchill is a town where people interact with polar bears often to the detriment of the bears themselves. It was also one of my dreams to see the Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights). I wanted to expose myself to an environment that was completely foreign to what I normally write about. The reason for the choice of Canada is that I am trying to come to terms with a country whose folklore has been imprinted onto me throughout childhood.

To confront such a landscape is in many ways to return to a story I have known, but in its physical reality. It's like looking at someone I recognise dimly through a glass shield. I was also determined to give something back to the environment while I was there. I was directed to the (CNSC) Churchill Northern Studies Centre from an online newsgroup on travel in Canada. Once I had contacted the centre they decided to take me on as a volunteer, which meant that I was able to stay for approximately four weeks working 4-6 hours a day for food and board. I would also have the opportunity to participate in lectures and, providing there were empty seats available, to go out on a tundra buggy and up in a helicopter to view the polar bears.

The Churchill Northern Studies Centre is about 17 kms away from the tiny town of Churchill, in northern Manitoba on the Hudson Bay. Churchill, whose population is 1,100, is a small seaport that is not said to 'get a boost' from the tourist industry every year, by being situated on the bears' migration path, hence its title 'the polar bear capital'. All polar bears are protected in Manitoba by law and there are an estimated 1200 polar bears now existing along northern Manitoba and in Ontario, Canada.

The 36 hour train ride straight north from Winnipeg, Manitoba gets in at about 9am three times a week. It was on the train the night before I arrived that I first saw the Aurora Borealis (The Northern Lights). They looked like big curtains of green light winding their way slowly through the clear sky above the spruce forest. While the lights might look close to the ground, in reality they are 60 miles above the earth's surface. The lights are caused by solar flares travelling out from the sun and enveloping the earth at either pole, and the electrons of that flare igniting with oxygen particles. There are legends about the lights and about the lights making sound.

|

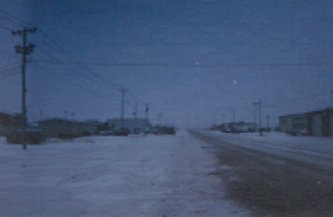

Once the train pulls into the town of Churchill itself, it's minus five degrees Celsius, a sunny day that is warm by Churchill standards, and the wind is coming from the south. The real cold wind is from the north, so it's easy enough weather to stroll around in with only a couple of layers of clothing on. The town looks like a seaport and is quiet, arid and isolated. It reminds me of the outback towns in Australia, but the geography and vegetation couldn't be more different. I have to keep reminding myself that hundreds of polar bears will pass through here on their migration to the ice of the Hudson Bay. When the bay ices over completely they will fish for seal. I hop off the train and go down and retrieve my luggage from the cargo compartment. A chilly wind blows through the carriages, under the wood where our luggage is stored and beneath my layers. It's colder than I think and my throat starts to smart.

The co-ordinators from the Northern Studies Research Centre are on the platform to meet the tourists and volunteers. We are driven out to the centre and I sit with the tourists who are concerned that the first snow hasn't arrived.

|

[Above] The main street of Churchill, Manitoba, Canada after a blizzard in late autumn. There is a 9.30pm curfew for locals in the town due to alcohol and drug problems, and a siren that goes off if a polar bear is sighted within the city limits. Polar bears coming into Churchill itself are a common occurence, due to the town being built directly on the bears' migration path. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1998) [Below] Polar Bear, Churchill, Manitoba, Canada. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1998)

I point out to them that if they want to photograph polar bears, then their white fur against the moss green forest and red grey rocks will show the bears up more in their shots. On the way out in the car I see a polar bear running along the shoreline of the Hudson Bay in the distance. It looks like a small white dog on the yellow pebbly sand. The landscape is a mixture of sub-arctic tundra and boreal forests with small lakes or pockets of water approximately 4ft deep above the permafrost in the ground below. I spend my first day getting orientated around the centre, which includes a tour and a lecture on polar bear safety. I find out that a cloudberry is a wild raspberry that runs along the ground. The Centre itself is an ex-military barracks and it's a big draughty place with many compartments and corridors, quite interesting, and there are many nooks and crannies where one can be private. I learn to distinguish between the footprint of a wolf, black bear, grizzly bear and polar bear. Residents of the centre are not allowed to leave the building unless they are accompanied by a staff member with a shotgun. I begin to hear the stories of polar bears looking in windows. Incidentally all windows and doors at the centre are protected by large steel bars at ground level. I visit the huskies who are chained up outside and who seem pathetic and starved for human attention. I look out at my first seemingly barren sub-arctic sunset from behind barred windows at the centre. This land is completely foreign to all I know.

[Above Left to Right] Adolescent Polar Bears, Churchill, Manitoba, Canada. (Photos by Coral Hull, 1998) Two adolescent polar bears playfighting along the shoreline of the Hudson Bay after first snow. The young bears are filling in time until the bay freezes over and they go off in search of seal which is their main food source throughout the winter months or while the bay stays frozen.

I tend to be quiet at first when entering new environments, absorbing information in the background, such as the conversations of tourists. The Centre had a conservation interest and various lectures by biologists specialising in polar bears, the arctic ocean and wildlife, through to dog sled operators, helicopter pilots, parks officers and adventurers, were taking place daily. There were often people who ate in the kitchen who had travelled to the north pole and across the south pole. It was great to be around that kind of energy and to listen to the stories. I attended all lectures and films with a notepad. My work was mainly cleaning but I was also working alongside professional tour guides. During the monotonous jobs such as making bunks, mopping the floor or general cleaning, I used to formulate ideas. For example, I begin to think about the ptarmigan, or 'tundra chicken', as it has been referred to by the locals. Ptarmigans are not the stars of the show, but they hold an attraction for me. They are from the grouse family and are sub-arctic willow fowl. I think of people's perception of them, the cook who said she 'hit two on the head and skinned them', the bird-watchers who admire them and the tourists who bypass their significance, once a polar bear strolls within camera range. I was fortunate enough to get close enough to a ptarmigan, so that its eye followed my camera lens. I also photographed polar bears.

[Above] A curious and hungry polar bear approaches a tundra buggy used by the local eco-tourist industry. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1998)

I took a number of bear photos in which the bears were either physically close to the tundra buggies or existed as part of the landscape. The reason for this was that I was interested in isolating the bears in order to establish a closer relationship to them, or to look into the mystery of the animal, and I was also interested in the polar bear in its natural environment. They awed me. I had only ever seen polar bears in zoos, or dead, moth-eaten and dusty in museums. To see polar bears in their natural surroundings was a privilege. Over the next few weeks I was to think about the ability of the polar bears to go out onto the vast icy wilderness of the Hudson Bay, to a place where neither I, or anyone else, would ever follow them. This gave me a great sense of satisfaction.

[Above Left to Right] The polar bears at Hudson Bay taste the first snow of the season. The vegetation is a characteristic specific to the Churchill area, where bears wait along the coast for the bay to freeze over. Polar bears are ice-dwelling animals, seldom found amongst vegetation. (Photos by Coral Hull, 1998)

Some bears returned years later from the ice and some were never seen again. It made the idea of exporting polar bears to zoos and circuses even more abominable. As a child at Taronga Park Zoo in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, I had always felt disturbed by the sad and psychotic bears swaying in concrete pits. My nan used to take me right around the entire zoo, from the top to the bottom, so by the end of the day we would be arriving at the bear pits as the sun went down. The sight of those sad white bears in the pits, who, under normal circumstances could smell out other animals in their icy wilderness from kilometres away, was deeply disturbing to me. I was frightened of them and sorry for them. I noticed that Taronga Park Zoo in Sydney has not replaced its bears, but bears are still being exported from Manitoba to zoos in tropical countries, where ice is replaced by grey concrete and a trickle from a hose. Polar bears have even been recently sold to a circus in Mexico.

[Above] A 'largish' polar bear rests in the snow along the Hudson Bay whilst studying the tundra buggy. Note that the bear's right ear is bleeding from tagging. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1998)

I will first write about what affects me emotionally. I begin to notice things about the landscape and formulate many comparisons between the tundra and the outback. This is called a cold desert. As we drive from the research station into the town of Churchill, the roads are gravely and icy so we sit on about 60 kms an hour. This same silent rule applies to driving on roads in the Australian outback that are affected by bulldust, sand drifts and rain. I think of the vehicle sliding on ice or sand. I was simply replacing the snow with red dust and the polar bears with kangaroos. In the town of Churchill itself, there are no shop fronts due to the extreme cold. In places such as Brewarrina and Bourke (in outback New South Wales), there are often no shop fronts due to the heat. We shade out house interiors and use fans, whereas here they have central heating. Malcolm Ramsay (a leading biologist on polar bears) asked why I was reading in the dark. He made the comment that light was precious to Canadians due to the long winter months. In Australia I was so used to shielding myself from heat and light, that I guess I had spent a lot of time reading in semi-darkness. He said, 'up here we let in as much light as possible!'

As a writer my skills aren't required in an area like this so I am an unskilled labourer. I was in the kitchen late one night and a snowy coloured weasel sneaking food from up beneath the floorboards nearly ran over my foot, a marvellous and dainty animal. I also got the story of Joan the cook pushing down on the huge doors in the delivery bay, and them being forcefully pushed back onto her. She continued to struggle with the door, thinking someone was playing games. Finally fed up, she stormed into the staff area and found that all the staff were on the inside of the building. It had been actually a hungry polar bear with her cub. Fortunately for Joan, she hadn't asked who was behind the door!

|

Sometimes as a writer I felt a bit out of place tagging along with the locals. If I'm going to extend my perception and subject matter, I think its important that I expose myself directly to my areas of interest. I wanted to connect with this environment rather than to internalise my perceptions or remain isolated from my surroundings, thus avoiding the trap of a limited experience.

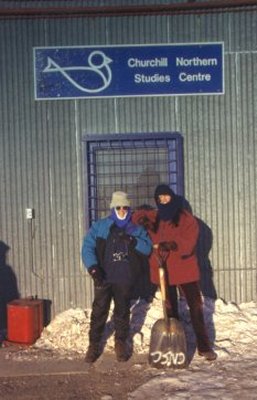

Yet now I could understand how hard it was to expose oneself to these foreign environments and to look for a place to fit in, while researching with no funding. Many tourists paid $1600 for the week to be a guest at the Churchill Northern Studies Centre.

At night after I quit work, I was able to study magazines and unwind or take notes at lectures. My notepad went everywhere with me. I would be happy to come away with even a few notes on this experience.

I also ended up working on something completely unrelated to what was happening around me. I had a lot of success with this, writing almost 20,000 words in my two days off.

The environment around Churchill, Manitoba appears to become simpler in winter. Birds have migrated and flowers that have died or gone into hibernation are no longer visible. |

[Above] Texan artist Karen and Coral Hull outside The Churchill Northern Studies Centre. Due to the high incidence of polar bears in the area, any trips outside of the Centre itself had to be supervised by armed volunteers. (photographer unknown, 1998).

Everything is blanketed with snow or ice as the north wind flattens it down to ground level. Even the trees are lop-sided, having most of their leaves on the southern side, with the northern side burnt by the frozen wind. I liked to formulate ideas against simplistic backdrops such as this kind of landscape, where anything seems to stand out, from a polar bear to the planet Jupiter. I always start from an obvious image and work my way in to the mystery of a continuing story. Association was sometimes a problem here, where I felt in awe or numb to the experience, followed by self-consciousness. To be fully present in an environment I must be relaxed and unconscious, at least for intervals. The more I think about what is affecting me, the more it doesn't. The trick is to notice what is affecting me and then to record it, as if I am simply living and not actually recording this living. Photography as an artform can be problematic for me. A feeling of self-consciousness can occur through the constant framing that is required and the presence of the equipment itself. By focusing in the camera I may become unfocused on my environment.

[Above Left to Right] Polar bears are viewed by tourists and photographers alike from tundra buggies, which are vehicles specially designed to traverse the rugged sub-arctic terrain. Bears can stand up to twelve feet high and are carnivorous predators and opportunistic feeders, making them incompatible with human beings. The impact of eco-tourism in the Churchill area is presently under scrutiny by conservation and wildlife groups. (Photos by Coral Hull, 1998)

There is always the piece of equipment to be dealt with, and to be conscious of that piece of equipment is to be conscious of yourself as both interpreter and recorder. Although, admittedly, there are many moments when the camera becomes part of the body and thought processes. These are my best photos, when I catch something like a good line, rather than stalk it, or deliberately set out to hunt it down. I enjoy the spontaneity of my thought processes with limited use of equipment. In this environment even simplicity is smothered in ice, and all the complexities of an ecosystem have either gone into winter hibernation or have migrated south. I found it easy to adapt my writing style to the landscape, and began by writing short surrealistic prose poems. By working in this particular way, I was able to utilise foreign images to suit my own creative purposes, without too much worrying about accuracy or fact. This was a case of abstract expressionism versus photo realism. I then hoped to take down a lot of direct notes inspired by biologists and researchers without much fantasy or emotional input.

The natural environment in its wintry simplicity didn't overload my senses. In addition to this, the physical space was very restricted within the Centre itself. In between working and formulating ideas, I tried to get a feeling for the area. This usually meant a combination of attending lectures, taking photos whenever I had a chance to go outside, talking to people and gathering written and other visual information. I usually like to get a feeling for the land including flora, weather, geography, fauna, and tend to ask lots of questions. Sometimes I felt insecure, because I wasn't a specialist in anything required by the centre. I have something to say about the experience of being present in this physical environment. Could the difference be that I call it art and the others don't?

I was only a visitor or an observer of their lives. How real does the situation become for a writer or documentary maker? Being an Australian looking at Canadian landscape was also a challenge. The first layer is my view of the physical environment. I try not to take photos but just to experience the animal, the northern lights etc. Then I take a photo as a kind of back-up process in the documentation, or if the composition is particularly startling. I also get other people's impressions and verbal descriptions, which I note down and sometimes agree or disagree with. In addition to this collection process, I form my impressions around a number of things. Then I collect or collate information on the area of interest, and go away to think some more on my own, where I will begin to write from rough notes. I do allow things to creep in, mainly to disturb or challange what it was that I thought I was going to do. In addition to this my own emotions and often unexpected events are never far behind.

[Above] Boreal forest consisting of black spruce and tamarack trees bordering the edge of Twin Lakes after snowfall. This area is approximately 17kms due south east of the Churchill Northern Studies Centre. The landscape consists primarily of sub-arctic tundra, with summer moss, scant vegetation and permafrost beneath the rocky terrain. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1998)

I tend to document my own emotional response to the subject matter as part of the experience. I then become absorbed in the new environment as quickly as possible. Usually what happens is, I get so absorbed, that I can bounce back the other way and write about something completely unrelated, such as, in this case, some prose fiction. I can imagine myself writing about Churchill in more detail once I arrive back in Australia. Yet it is very important while I am in an area such as the sub-arctic, to expose myself to as much physical stimuli as possible, from minus 45 in the wind, to walking on ice and hearing the sound it makes, to washing up tourists' dishes in the kitchen at 11pm each night, to seeing Wally the weasel sneak in. I seem to have an immediate reaction to physical environments, and tend to absorb things very rapidly, such as in the case of a description of a situation. More often than not, I am emotionally affected by a physical environment and my place within that environment.

On one occasion, biologist Malcom Ramsey was looking at some infrared images of polar bears by night, that could accurately deduce the body heat of the bear. He was interested in ascertaining how play fighting between sub-adult male polar bears affected body temperature. He produced a few slides during the lectures. Aside from their scientific significance, the slides were clearly works of art. Coming from an artist's perspective, I immediately pictured them in an exhibition of some kind with accompanying text. Where these scientists let me down was that they wouldn't speculate on whether animals could think or not, or whether animals were intelligent or had their own language. I guess they were biologists rather than behaviourists. It is pretty clear to me after many years of associating with animals and growing up with them that we are of the same cosmic dust, possessing similar physical as well as psychological traits. Sometimes the scientific becomes unimaginative.

After visiting hundreds of galleries over the past ten years, I've noticed the limitations of visual arts restricted to its own schools, trends and fads rather than the world outside itself. To me these slides represented the outside world. They would never be used in a gallery with poetry, because Ramsay was no poet and most likely wouldn't want them there. To him they were data and not something 'high flung' and 'out of touch', such as the visual arts. The other reason they would not be in an art gallery, is that most visual artists would not be in these environments to recognise them as art, and even if they wanted to be in these environments, it was unlikely that they would be invited there. These were hard borders to cross during my Churchill visit. There was really no reason to take poets across Antarctica or the North Pole, in the same way that there is no reason to take them to the first space station. The people who worked in these environments wanted environmental scientists, biologists, engineers, pilots and researchers specialising in the area. If this is the case, then I'm wondering how poetry or the visual arts can ever hope to accurately document these situations. It is my opinion that poetry needs browse through both internal and external environments, becoming the creative bridge or the viewing platform to the soul and to the world. I knew that my Churchill experience had challenged me on these levels.

[Above Left to Right] A helicopter is hauled from a huge storage shed outside the Churchill Northern Studies Centre after snow, and with more snow expected. Helicopters are used by biologists for bear-tagging, to bring in specialist supplies to the Centre, and by the eco-tourist industry. (Photos by Artist Karen and Coral Hull, 1998)

For me it often takes something simple to overcome feelings of disconnectedness. In this case it was finding a book titled Wilderness Visionaries complied by Jim Dale Vickery, containing various writings of wilderness lovers, such as Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Robert W. Service, Bob Marshall, Aldo Leopold, Olaus Johan Murie, Calvin Rutstrum and Sigurd F. Olson. I began to think about writers in Australia who documented landscape and my place amongst them, and this excited me. I often find myself looking for permission, a place, and instruction in order to write. A cleaner is a cleaner and a biologist is a biologist, but what is a poet and how can writing poetry be justified in the surroundings of the Churchill Northern Studies Centre and the sub-arctic landscape?

This book gave me permission to be who I was in a foreign environment. These writers wrote about the northern hemisphere in a deeply personal sense without sentimentality or romanticism, and so I began to bounce off their ideas and ways of working, while thinking about Australia, which is where my primarily focus is in regards to landscape documentation and interpretation. It was interesting to read that many of these writers had lived the experience, rather than merely researching it, by becoming involved in social issues and actually founding many of the environmental organisations across North America. It made me think of the Australian poet Judith Wright, and her efforts with aboriginal people and The Great Barrier Reef off the coast of northern Queensland.

One of my jobs at the Centre involved cleaning the helicopters with another volunteer named Robyn who was studying polar bear biology. We approached the shed where the helicopters were parked by car. We shone the headlights around the area in a quick check for polar bears, who can easily conceal themselves amongst the willows and the snow on twilight. A couple of days previously, I had seen a polar bear turn its head so fast that it appeared as if its head was in first one position and then another, with the movement between the two positions too fast to detect. I assumed one could hook you from out of a vehicle, about as fast as hooking a ringed seal up from an ice hole. We pulled up at the big shed after having spotlighted the area. Robyn said that a polar bear had been up on the roof of one of these sheds that week. They were apparently attracted to rubber and petroleum products. We left the engine running and the car headlights on, leaving a large space at the front of the vehicle, so that on our way back out, we could again check for any bears that may have crept up.

|

I know that in the Northern Territory, Australia, a salt water crocodile will move down to the place in the river or billabong where someone has collected water, waiting for them to return. However, Robyn said that polar bears weren't like this and would most likely simply wander in, out of curiosity.

We spent the next hour or two inside a huge lit-up shed with two helicopters. Cleaning the helicopters was a vast and meditative process, far more like cleaning expensive crockery than a factory floor. Each blade and side had to be polished and I found myself taking the same care with the craft as I would have when showering or bathing my own body. We had to climb up onto step ladders to wash the top sections and rear propellers. The side doors were extremely fine; it was like handling glass plates or putting two separate pieces of shell back together, each of which had held life. After the cleaning was finished, everything was switched off by Robyn as we left the premises, and again we checked for bears in the car headlights. Finally we made a dash for the doors. We drove back towards the centre along the ice and I had a feeling of satisfaction that I didn't think I would get from cleaning the machinery inside lit-up sheds, with the furnace gently burning, inside a very cold and frosty shed interior. |

[Above] A newly cleaned and polished helicopter inside one of the storage sheds. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1998)

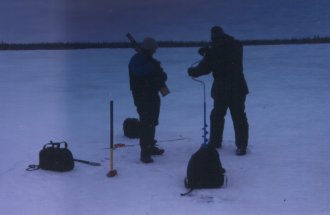

One of the highlights of my stay at the Centre was spending a full day with an artist named Karen who was working on a mural, and an earth scientist who was involved in measuring the depth of ice in the local lakes. Karen and I wanted to get more of a feel for the surrounding area. One of the problems for us both was the claustrophobic atmosphere of the Centre, including its internal politics and being surrounded by tourists. I had also missed out on experiencing a lot of things such as a bear lift, which is where a so-called troublesome bear, usually a male adolescent, is tranquillised and air-lifted to a town compound where they are temporarily put under observation. The lack of opportunity to do such things was due to the fact that I was there to clean and not to create art. Nevertheless, the staff at the Centre were very generous, and I managed to get out on a few occasions such as this. The day was spent walking the length of two large lakes called 'Twin Lakes' which now in the late autumn were completely iced over. The immense silence of a wilderness like this is amazing and it is very similar to a desert silence or 'deafening silence', where the loudest noise becomes your breath, presence, heartbeat and your own footfall through the ice and snow. In fact, the arctic is an ice desert. Our purpose in walking the length of the lakes with the earth scientist was to manually drill down to the water beneath the ice and then to take measurements of the thickness of the ice along the length, width and breadth of the lakes.

[Above Left to Right] Ice drilling on Twin Lakes with an earth scientist, artist Karen and Coral Hull. It is about minus 15 degrees celcius at the time the photo was taken. Note the hand drill, yet another technological breakthrough courtesy of the Churchill Northern Studies Centre. (Photo by Karen and Coral Hull, 1998)

This was simply to test the effect of the greenhouse weather patterns on overall ice thickness. Malcolm Ramsay had mentioned that if the greenhouse effect continued to go the way it had been, polar bears would be extinct within the next 25 years. This was because they are an ice-dwelling animal, who depend on an ice environment for survival. Polar bears live, breed, hunt, play, sleep and die on the ice. Their primary food source is seal which they hunt as they come up for air at their holes along the landscape of ice. If the ice melts, the primary habitat of the polar bear is no longer existent and they will die out. We also walked into the black spruce and tamarack forests surrounding the lakes and measured snow levels.

[Above] Arctic Fox in first snow with summer colouration, Twin Lakes, Churchill, Manitoba, Canada. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1998)

The earth scientist carried a firearm with warning shots for bears and real bullets. I was a little bit nervous, as bears had been sighted in the area less than a kilometre away, and they were opportunistic feeders, which meant that we weren't off the menu. During the course of the day, my feet gradually froze inside my shoes and at one point they were really hurting. I alleviated the pain by jogging on the spot to try and get my blood circulating, although I have been told by other Canadians that it's when your skin and other body parts stop hurting that you've got to worry. That is basically when the skin freezes and dies. The peanut butter sandwich and apple that I had packed for lunch were also frozen solid.

[Above] Canada Grey Jay, Twin Lakes, Churchill, Manitoba, Canada. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1998)

During the morning we had a family of Canada Grey Jays come and take a few crumbs from us. Ordinarily I'm not one to feed native wildlife, but couldn't help myself with the determined hungry little birds. They looked so tiny and yet hardy with their fat breasts against this brilliant harsh white landscape. It was interesting to hear the way that the waters in the lake shifted and creaked below the ice covering. At one point, it was almost as if the lake was growling. We saw an Arctic Fox or two as well. Out along the second lake in the afternoon, some rain came in and soaked us. But afterwards the water quickly froze on our clothing where it formed a hard shield of ice, which acted as a barrier for protection from the wind. One of the Arctic Foxes was rolling around in the ice on the edge of the lake in order to remove the icy crust of rain from its coat and tail.

What I did notice was that winter had come late this year. I was told that this was due to all the weather patterns being altered by the Greenhouse affect. Most of the local animals had turned white out on the tundra, before the snow had even properly fallen, including Ptarmigans, Arctic Fox, Arctic Hare, and Great Snowy Owls. A couple of howling three-day blizzards that came down from the north brought a good fall of snow to the area while I was there. However, this colour change occurring in animals occuring before snow makes all of them more vulnerable to predation.

[Above] Texan artist Karen and the earth scientist walk down an embankment and out onto one of the snow-covered lakes, Churchill, Manitoba, Canada.

The earth scientist comes out here every year to check the ice levels at Twin Lakes, which is about 17km from the Northern Studies Centre. It was a long cold day at minus fifteen degrees Celsius; nevertheless, I found that I was able to absorb far more by being out in the landscape first hand, rather than experience the excited second-hand stories of wealthy American tourists visiting the Centre. The Texan artist did the same. She was going to paint a mural inside the Centre of a prehistoric Churchill scene. We both agreed that we needed the land to be within us before we could adequately reveal and recreate some of its characteristics.

[Above] Polar Bear #5, Churchill, Manitoba, Canada. Caption: A polar bear or 'ice bear' is one of the world's most sophisticated predators. (Photos by Coral Hull, 1998)

On another occasion at the Northern Studies Centre, I had seen this elderly Indian man eating jam and bread and being shown around by his assistant. A couple of the volunteers said that he had started talking about the old ways and traditions. He was also giving a lecture, but I didn't bother going. I felt a overloaded with information and I was also feeling fed up with native hunters and all the killing, after having seen a wolf skin for sale for $800 in the local souvenir shop in town. The wolf, caribou and moose secrets that were kept from the hungry little town of Churchill were probably best kept as secrets. It turned out that this man was a modern-day shaman. He was at the Centre because he intended to conduct an outdoors ritual, in order to send the polar bears off along the ice of the Hudson Bay, and to wish them well on their journey north. This quickly gained my fascination and a few volunteers and some of the Centre staff were fortunate enough to be able to accompany him.

During the ritual we stood at the edge of the freezing Hudson Bay while he performed with song. When a few of us arrived from the Centre, he was facing north towards the bay itself, with no cover on his arms, hands, face or head. He was singing this high galloping song that had a sense of longing to it directly into the north wind. The ritual was for wishing the polar bears well on their journey across the Hudson Bay once it had iced over.

|

He had a small altar composed of pipes, coloured rags, crystals, animals carved in various substances such as bone, and his spear like the prow of a ship sailing out to sea. The singing was so sincere, and I couldn't help but be touched by it. Indigenous cultures normally sing about themselves, their hunting and ceremonies, and their own problems and lifestyles. What I particularly liked about this, was that it was a song for the winter and for the polar bears, without the constant presence of and focus on us. |

[Above] The formidable wind and waves of the Hudson Bay roar along the icy coastal rocks in early winter, before the bay completely freezes over. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1998)

My face was stinging from the cold and falling snow, so that I was forced to turn sideways. On the way down to the edge of Hudson Bay, I was the straggler through the big coastal rocks covered in snow. A fear of bears got me running across the uncertain surface, until I caught up with the others without tripping over. Standing behind the modern day shaman and his song, it was like we were all riding a great ship out into the grey north wind, the snowy shore and the huge grey breakers crashing in from Hudson Bay. It was like the land was moving beneath our feet, carrying us all out into the area that we sang for. He was singing inside my heart. A narrow strip of sky cleared in the areas where he was singing, exposing a strip of icy watery lime-green, and two ravens that I had noticed in the area on the way out flew overhead. Later I was to be told that ravens are his totem animal. I could feel myself drifting in and out of my body as he sang. These were acute moments when all was like a prayer for the polar bears, three of whom we had seen walking in the snow on the way out. The shaman then buried the four coloured rags and sang his songs into them, and had a puff on a pipe with a polar bear motif on the end.

During this song, his assistant had been bashing on a hide drum with a polar bear painted on it. After attending to his shrine briefly, he then sang another shorter, fainter song more resigned in tone. He then turned and told a small group of about twelve of us that he would now go out to the icy surf of the Hudson Bay and dip his spearhead into the water. We followed him part of the way down. I stayed well back, watching him at the great edge of the bay. The ritual seemed to be a bringing-together of all the beauty of the winter, the bay icing over and the bears leaving the mainland across the ice.

[Above Left] A ptarmigan on the tundra with winter colouration in late autumn before first snowfall. Small flocks of ptarmigan usually take shelter from below-freezing winds in snowdrifts and tundra willow. [Above Right] A mother polar bear and her adolescent cub walk along the rocky tundra to the edge of the Hudson Bay. (Photos by Coral Hull, 1998)

They were to live out their lives on the ice, as he threw his blue rag into the ocean with the head of his spear, his hands up over his head. On the way back, he grinned and caught my eye. He was pleased that we had followed him down to the edge of Hudson Bay. I thanked him by nodding, fearful that my voice would crack with emotion in front of the others, if I tried to say anything. It was getting suddenly cold with a blizzard of snow coming down from the north over the bay as we turned back to the vehicles. I was no longer cold. I removed my head gear and scrambled and ran across the foreign snowy surfaces.

I've always been attracted to and felt comfortable in these big, expansive landscapes and wilderness areas that offer extremes and give a sense of simplicity. Of course, no ecosystem is ever simplistic, but the very landscape is relaxing to me and allows my inner creative processes to come to the surface. The landscape of ice is a white sheet of paper that is about to be written on. I guess the sub-arctic is somewhere that holds my interest and that I hope to return to in the future, in the same way that I perpetually return to the Australian outback. On my last night at the Churchill Northern Studies Centre, I sat up in the observatory dome where the astronomers go to view the northern lights. The sky was light grey and overcast with snow and light flurries. I thought of the astronomy group that I had been part of, who had experienced a substorm of Aurora Borealis before the last blizzard had set in, our tiny warm bodies out in the clear dark autumn, looking up at the huge northern hemisphere night sky and lights that stretched into eerie green bands. It was minus 45 degrees Celsius in the wind, and, I would guess, minus 20 standing behind the corner of the building and the utility. I had on five layers of clothing, including a thermal coat, two pairs of socks and waterproof boots, with my toes the first things to freeze. Nevertheless, I was just a moment away from proper heating. I think they call this a soft adventure.

[Above] There is a thoughtful and gentle side to the great predatory ice bear who thrives in one of the harshest environments on the planet. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1998)

The storm of northern lights was extraordinary that night. The entire sky overhead lit up with red, yellow and green bands that seemed to spiral into a point and then pour down upon us all. Rodger was the lecturer on astronomy from the observatory at Winnipeg. He said that he had never seen such a magnificent substorm. He told us that the solar activity on the surface of the sun was set to increase in the next couple of years, bringing more such storms to these areas. It was a real privilege to have seen something so beautiful as the Aurora Borealis, the wild white bears crossing the ice on their big pads, the twisted boreal forests of black spruce stunted by the cold and the permafrost, and the rocky icy geology of the land that faulted and sank, and that eventually descended from sub-arctic forests, to tundra crossed by herds of caribou, to yet more and more barren ice sheets and ocean towards the magnetic North Pole. In the sky above me, it was minus 60 degrees Celsius in the late autumn wind. The eye of Taurus was low down along the horizon and blinking red, and there was Jupiter with its distant satellites half in shadow from the sun, and the stars and the green curtains of light.

I felt close to the top of the world. It was like a dream coming to live inside me. Each time I saw the northern lights or the 'polar night lights', as they are called, I wanted to sleep beneath them as if they were a blanket thrown over me by some superior and protective force. I felt safe beneath them for the first time since I had been a child terrified of the dark, with my night light curled up in the sheets of my summer bed. There was no fear of life or death beneath this particular sky at Churchill, and it was as if everything was as it should be.

About the Writer Coral Hull

|

Coral Hull was born in Paddington, New South Wales, Australia in 1965. She spent her childhood in Liverpool, on the outer western suburbs of Sydney. Coral is a full-time writer specialising in poetry, experimental prose fiction, scripts and literary articles. Her work has been published extensively in literary magazines in the U.S.A., Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom. She is also the Editor of The Book of Modern Australian Animal Poems, an anthology of Australian poets writing about animals from 1900-1999. Her published books are: In The Dog Box Of Summer in Hot Collation, Penguin Books Australia, 1995, William's Mongrels in The Wild Life, Penguin Books Australia, 1996, Broken Land, Five Islands Press, 1997 and How Do Detectives Make Love?, Penguin Books Australia, 1998. Coral is an animal rights advocate and the Editor of Thylazine, an online literary magazine featuring articles, interviews, photographs and the recent work of Australian artists and writers working in the areas of landscape and animals. She completed a Bachelor of Creative Arts Degree (Creative Writing Major) at the University of Wollongong in 1987, a Master of Arts Degree at Deakin University in 1994, and a Doctor of Creative Arts Degree (Creative Writing Major) at the University of Wollongong in 1998. |

[Above] Photo of Coral Hull by Cliff Hull, 1999.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.1 (March, 2000) |