LANDSCAPE AS INSPIRATION AND PAINTING THE POETS

By Jenni Mitchell

[Above] Jenni Mitchell painting saltlake near Jeparit, Victoria. (Photo by Bohdan Kuzyk, circa 1987)

Growing up in Eltham, I suspect, has a lot to do with my love and respect for the natural world. During my childhood, Eltham could still be considered a village; faces were familiar, everyone knew each other, and the ice developed on puddles in winter - and stayed there. Being an only child also helped me to develop sensitivities to observe what was around me. I had a lot of time to learn to amuse myself ... there were books, pens and pencils to draw with and the small world of the square foot of grass seen from laying down on hands and knees to spy what was there. I remember as a child looking deeply into the world at the centre of a flower, taking my mind on a walk along the colourful powdery velvet-walled tunnels, and tasting the nectar of the blue periwinkle that grew abundantly around our old house.

My mother would take me by the hand as a small child and we would walk around the block; she pointed out the various native flowers, the greenhood orchids, spider orchids, chocolate flowers with their delicious scent, the true sarsaparilla creeper, running postman, early nancies, milkmaids and, my favourite, everlasting daisies. The Eltham of my childhood consisted of a rural township and countryside with paddocks, trees, creeks and rivers. There was a radio to listen to the Argonauts Club; there was no television in our house.

The park across the road from my parents' home was my bottom paddock. I knew each tree individually; its personality and spirit. This park was an untamed space where shrubs, grasses and maidenhair fern grew wild along the creek banks and the ever-filled spring. There were places to feel good, and dark spaces to feel apprehensive and nervous to enter. This place was as much part of my consciousness as my own bedroom; the sculptured shape of the burnt-out tree stump that was hollow inside and into whose deep blackness one could peer, the silvery frosty bark of the tall manna gum, standing straight and strong ... the laugh of the kookaburra and my hands raised to ward off the nesting swooping magpies. The land had magic and a life of its own, in both the broadest vision and the smallest observations, as with the struggle of the ant dragging a large morsel back to the nest.

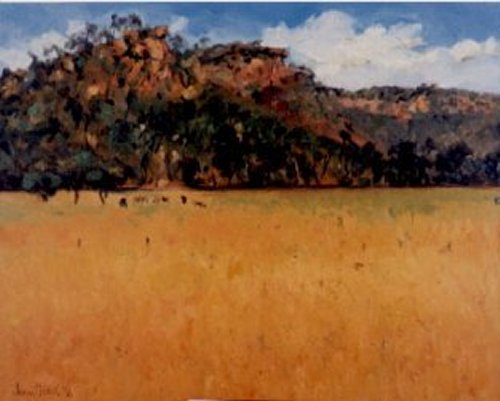

[Above] Pulpit Rock, Bundanon by Jenni Mitchell. (oil on canvas 1996 20" x 24")

My first trip into arid country was when I was 18 and travelled from Melbourne to Mildura and on to Broken Hill. Instantly, I fell in love with the landscape across the Great Divide. Along the highway through Hattah Lakes National Park towards Redcliffs and on to Mildura I saw the first of the sandy country and the spinifex that I had looked at previously only in books. I cannot explain my excitement and connection to this Mallee landscape. It was as if there was an energy change ... a wholeness of sorts. Different landscapes can give different feelings, as if responding to hidden spaces inside us ...

I dreamed of the desert. My first art book was of the paintings of Albert Namatjira depicting distant purple ranges and white ghost gums. I looked into the foreign places and spaces for hours ... I had picture books of the Arizona deserts and the African plains. I wanted to be there. I saw images of grass trees; they seemed so exotic and alien to the yellow box trees of my Eltham landscape. I began to copy these pictures and photographs at the age of ten when I had secured my first set of oil paints. I painted the desert and the rocky landscape ... I couldn't wait to set foot inside Australia.

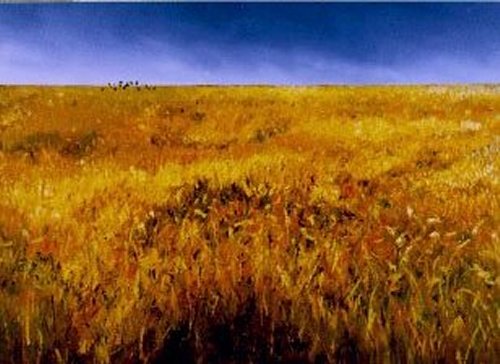

[Above] Wild Grass Fields by Jenni Mitchell. (oil on canvas 1997 3' x 4')

Then there were the plains above Mildura as I headed towards Broken Hill. To stand in a landscape and look towards the horizon at endlessness ... long stretches of what some people call nothing ... empty, and yet within this space is everything, abundance. The landscape may appear quite treeless and without recognisable vegetation, the soil may look poor and sandy; it's a matter of observation. Instead of emptiness, I began to see the shimmer of a mirage and the appearance of water in the distance ... the saltbush, mintbush and native grasses growing from the sand giving home to much wildlife as seen by the myriad tracks left by small and large feet indented in the sand. Closer observation showed stashes of seeds collected by small rodents, lizards and insects, and emu tracks. The quieter one becomes, the more is revealed. Stillness is best. Birds can be seen living amongst the low shrubs of the saltbush, nesting in the low mulga tree, hawks above and eagles, circling and riding the thermal winds, at times disappearing from sight in their height. Stock wanders freely across this country, a mob of horses, cattle and sheep; there are no fences.

I began travelling into this landscape with my paints and camera, camping for weeks at a time under the stars. Each day the city dissolved from my mind as the location became home. After a few days, I would feel I had arrived at the landscape. I would forget what day it was, watches were not worn and I would tune into what life in the desert meant. And for the artist, and writer, that was simple meals and painting, or writing ... a slowing down and tuning into the natural being, rising at daylight with the first rays of sun lighting the grasses then setting them aflame with gold light ... breakfast to the dawn, then capture it on the canvas ... paint the washed-out light of midday when the land is bleached and colorless - or is it? The afternoon colour would return until again the sky was rich with deep reds and yellows westward, or more subtly pink and mauve in the east. The night sky would arrive with its velvet ink jacket and millions of tiny white stars sprayed across it. The Milky Way seen without city lights is another experience. To see the night sky as a wilderness sky is something special.

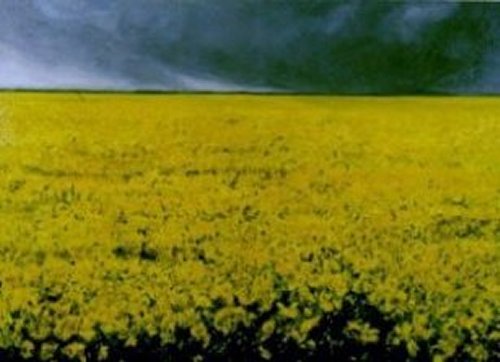

[Above] Canola Field by Jenni Mitchell. (oil on canvas 1996 3' x 4')

I have spent a lot of time in various terrains around the country: the vast Canola & wheat-fields of the Wimmera; the rugged granite outcrop of Mt. Arapiles and its dry white salt lakes; The Little Desert, and its wide diversity of vegetation - low salt-bush, grass trees, banksia forests, abundant wildflowers; the Mallee with its forests of Mallee gums, wonderful salt lakes, including the Pink Lakes National Park where soils containing carotene have turned the salt waters pink, and salt crystals cling to twigs that fall into the waters. All of these places cannot be understood or seen in a day. Many trips back and forth must be made.

Camping is an excellent way of experiencing the country, and allows the artist to observe the land in all lights, and the night sky. There is nothing more exhilarating that to sit around a camp fire on a warm evening watching the shiny blackness of the night sky with the glitter of the milky way strewn across the canvas. It is magic to sit on the land and see a meteor shower. It makes you feel good, close to the earth. It makes you feel inspired and want to paint not only a daytime earthscape, but the night sky as well. It is worth the roughness. After a few days the city can be shaken off, and the dust of the land invades your pores.

While camping you are able to experience the full beauty and intensity of the Australian sunset. If staying in a house or hotel, you are usually travelling back home while the best show is on! Camping will enable you to continue painting into the twilight. The evening landscape, the setting sun, the first glow and then the second afterglow, when the sun has fallen behind the horizon - these need to be observed for a period of time. Then when you feel it in your bones you can paint it. After beholding the brilliance of the flaming red, gold and orange that streaks the west, it is worth looking away from all the fire, looking instead towards the east at the soft, gentle blues, pinks and mauves of the opposite light. This is sometimes even more beautiful. These gentle colours wash out altogether as the night sky descends into deep maroons and indigos. The first stars appear, and the night revolves into mysterious blues, and then the blackness of the finality of day.

[Above] Sunfire Cloud - Triptych by Jenni Mitchell. (oil on canvas 1990 4' x 15')

The landscape artist must know these hues, the way the various lights fall onto the land, the tones and shapes of the land as the day turns. A camera snapshot cannot capture all this. I will use the camera as a memory prompter later on - particularly transparencies, which gives a much truer sense of the light's intensity.

Sometimes the journey is itself an important part of the process. I travel regularly to the Flinders Ranges in South Australia. This is a two-day journey from where I live in Eltham. Firstly, there is the planning, preparation and packing, which require a certain discipline. I must prepare for all possible subjects, and thus take the materials to cover this. My rule of thumb is to just take everything - better to have more than less. So I always pack my oils, gouaches, pastels and camera. Nothing more frustrating than a subject that demands to be painted in gouache, or having an urge to paint in oils, when I haven't brought them. Best to bring materials home unused and know that they are there!

Once packed, in the car and on the road, there is a sense of excitement for the journey ahead. No matter how often you have visited a place before, there will be something new to discover. I experience the Finders Ranges in South Australia differently each time I go there. It is as if a different facet of the land is constantly revealing itself to me. Initially, I was struck by the grandeur of the open spaces, and painted the long vistas, huge skies, day and night and the open plains. On my next visit, I looked more at the gullies, the vegetation, and the soils. On later trips, the rocks, and then later the earth underfoot. Next time I will find another focus. Perhaps a single flower of the desert, an insect or a leaf.

I have always felt that it is helpful to walk into my subject. If a particular subject inspires me, I will often set up my easel, prepare the canvas and set out into the landscape to absorb the colours and textures.

[Above Left] Bush Floor Study 1 by Jenni Mitchell. (oil on canvas 1997 14" x 14") [Above Right] Blackwood Road, Ash Wednesday by Jenni Mitchell. (oil on canvas 1983 3' x 4')

I have found endless subject matter in the Flinders Ranges. Millions of years of volcanic activity and shifting layers have left the most unusual shapes - worn-down hills, harsh cliffs that tower over dry riverbeds or turbulent waters when flowing. Sometimes a riverbed looks extremely inviting to camp in; this is not good practice, however dry it may seem. Rain could fall one hundred miles away, setting the rivers running, and without warning you're in a terrible predicament! Rivers can rise and fall within hours. There is a wide variety of wildlife throughout the ranges. For instance, in the land in the Chambers Gorge area you may be lucky enough to come across the Yellow Footed Rock Wallaby; a terribly shy but beautiful wallaby with yellow markings. There is usually some water in the creeks around Chambers Gorge. Permanent waterholes foster an abundance of bird life, water birds and parrots. They are beautiful places to camp and paint. A wonderful subject here is the contrast of a dark waterhole against a rocky outcrop, or water edged by the variety of coloured slate that makes up the riverbed. The riverbeds themselves are most colourful subjects to paint. A walking trip with the gouaches on your back will take in the Aboriginal art gallery. Some of the oldest rock carvings in the country are found in this area.

Other sources of great inspiration in the Flinders Ranges are the numerous Station properties. Beltana Station is one of my favourites. Steeped in early pioneering history, it has many stone buildings, shearing quarters, sheds and homestead, which all serve as interesting subject matter. Views of the surrounding country are magnificent from the homestead hill, and you may glimpse the mystical Sturt's Desert Pea. Beltana Station played an important role in the development of the Flying Doctor Service, and was the point from which several explorers set out on their wild treks. Nearby is historic Beltana township, with a number of heritage buildings still standing; one of them is the pub, restored over a number of years and now a residence.

There are many station properties throughout the Ranges. Some have splendid sand dunes; others waterholes, creeks, gullies and grass plains. Wedgetailed Eagles are a common sight, along with mobs of kangaroo, emu, sheep and cattle. The ancient River Red-gums are themselves worthy of a portrait. These trees stand as sentries along the dry creek beds.

They tell us that water is still available, and offer a home to the wildlife, birds and goannas, and shade for the artist at midday beneath their expansive limbs. One can experience the quiet stillness in the land, the silent shimmer of a midday heat mirage on the horizon, or feel the biting howling wind from the west, a quiet night by the camp fire, or a country band at the local watering hole, the outback pub.

[Above] Jenni Mitchell painting at Tibbooburra, New South Wales. (Photo by Bohdan Kuzyk, 1989)

During my three-month stay at Parachilna in the Flinders Ranges, I was lucky enough to have access to the then-empty Parachilna School House. I was artist-in-residence in the township, and this became my temporary studio and base. I was able to stretch canvas and hang my work around the walls and basically enjoy the full benefits of my Eltham studio right there in the desert that I was painting. This was a great advantage: large paintings could be executed on site and I didn't need to wait until returning home to produce major works. During the day, and early evening, I would paint smaller works on location, or make pastel drawings that would form the basis for the major works completed in the Parachilna studio.

Interestingly, despite a three-month stay there, I still do not feel that I know and understand that landscape. I have been back and forth many times, usually for stints of only a few weeks, but it remains mysterious, new. The Flinders Ranges in South Australia is a unique place and one that will offer an enlightening experience to any artist that takes their first journey to this country's heart.

Most of my work is completed on location. Large paintings, of course, require a studio, working from smaller sketches and paintings. Part of the interest is the quest for unusual subject material. Often this takes me to the inland, such as the Flinders Ranges or the Lake Eyre district in South Australia. Here I seek out the intense light, mood and dramatic sculpture of the land, a relentlessly flat horizon line, barely broken by vegetation, or a dark waterhole at the base of an ancient rocky outcrop. The desert, for me, holds everything. The endless horizon line, a clump of spinifex, or the single gibber stone underfoot, are a lifelong source of subject matter and inspiration.

By contrast I seek heavily-vegetated landscapes: the melancholic beauty of a reflection in a black waterhole, the mist that rises in the early morning from the stillness of a tidal river, a pond with an unbroken surface, first or last light. I always like to walk into the landscape I am about to paint. As an artist who loves the natural environment and seeks out the unusual and remote landscape, I will never fully experience in my lifetime those places that I have painted. My still-to-visit list is endless.

There are many similarities between landscape painting and portrait painting. Both are observations of the natural spirit. The portrait artist aims to bring out the inner person, the soul, personality - call it what you will. The landscape artist does the same. A landscape painting is more than just a picture of hills and trees. A good landscape painting should give the viewer a sense similar to that of the portrait, a sense of inner spirit, soul or personality of that land.

[Above] Black Pond, Kinglake National Park, Victoria by Jenni Mitchell. (oil on canvas 1992 30" x 36")

In portrait painting I work directly from the subject using photographs purely as a record and reference. It is important to engage with the sitter, for a portrait demands more than mere observation - the more time spent with the subject, the closer to the true spirit of the person you come. I am sometimes reluctant to use the word soul, preferring to use 'trueness'. The backgrounds are extremely important to each portrait, representing the colour relationship or subject material that reflects the person's life or work.

How can the poet write of the landscape or the painter paint it from a photograph ... and hold conviction in their work? It is absolutely necessary for the artist to spend time in the landscape if the work is to have any substance and depth of feeling. On my many travels, I like to discover a place and get to know it, become familiar with that landscape. I will not be satisfied with just one visit. I believe that the best paintings are those for which the artist has spent time living in a particular environment, breathing the air, experiencing night, day - its very spirit. The land must be felt and lived. To live and feel the dust on your skin, to become one with the land, become the colour of the land, feel the different spaces, fear and delight, the whimsical, the difficult, feel the scratch of the thorns, the stones under your shoes, the softness of the clay, the joy of a refreshing waterhole under a scorching sun, or the chill of a desert wind in spring when the sky is a vibrant blue. To walk along an ancient river bed in the Flinders Ranges, or pick up a tektite fallen from space, strange lights in the night sky ... the landscape inside Australia is everything.

To experience the land and spirit of the country I have found it best to go without music or man-made interference. If quiet enough, and still, the land will talk to you. First there is the sound of the wind, more noticeable if it ever stops ... the sound of the birds, diamond doves, the crow and the raven, with their woeful cries across the land. In time it is possible to tune into the landscape's rhythm, the hum. It keeps you company ... I never feel alone in the great wide spaces; there is always a presence and many subtle changes to observe.

In contrast to the inland are the quieter and not-so-quiet places around the coastal regions of Australia. The Port Campbell region with its fiercely wild winter seas can give one a sense of being alive ... to feel the icy wind rippling through your hair and tearing at your clothing - then to watch the fairy penguins risk their lives in the surf to clamber onto the beach and make their way home to nest.

The desert and the sea have a common visual thread for the artist. I have stood at times in the desert and seen the sea, the long flat horizon shimmering with heat giving a sensation of water and waves, the sound of the wind and the rhythm of the landscape, the movement. Sometimes, I have thought the only difference is the smell and the colour; the composition remains similar.

I have been asked at times why there are no people in my landscape work. The answer is simple: they get in the way of what the land has to say. I suppose, in a sense, I paint landscape portraits. I want the viewer to see and experience what I feel when I am in the landscape; the addition of human figures would only confuse the experience. However, I do paint portraits of people: poets.

Painting The Poets

[Above Left to Right] Les Murray by Jenni Mitchell. (oil on canvas 1992 36" x 33"), Coral Hull by Jenni Mitchell. (oil on canvas 1999 36" x 30"), John Kinsella by Jenni Mitchell. (oil on canvas 1999 36" x 30"), Rob Adamson by Jenni Mitchell. (oil on canvas 1998 36" x 30"), Judith Wright by Jenni Mitchell. (oil on canvas 1989 36" x 30")

In 1982 I began painting portraits while a student at art school. It wasn't that I particularly wanted to paint portraits of poets; it was more that these were the people in my life at that time. Again, living in Eltham near Montsalvat I was often asked to host some of the interstate poets attending the Montsalvat National Poetry Festival. Nigel Roberts, Prof. A. D. Hope, Cornelis Vleeskens, Ken Taylor, Terry Gilmore and Chris Mansell were among the first poets I met and painted. I felt as a painter there was a sharing of vision or values; I had an affinity with these people. There was a connection with the land and spirit of living in this country. Although each poet was unique in their work, there was a similarity; perhaps it was an easy-going attitude to living ... each one of these poets, to me, as a young person, struck me as being able to rise above the everyday and see life objectively - they were not concerned with a common fashion. At least, that was my impressions, of these poets back then.

Those first few paintings have become a series of Australian poets' portraits, of which there are to date 94. Some of the poets have been painted more than once. For instance, Alec Hope (A.D. Hope) sat for me three times, twice in 1983 and again in 1989.

In some respects, working with each poet is not unlike working with the landscape. As each new valley or plain is unique in the sensation it gives me and I look freshly at how to tackle the subject - so is each portrait. I have found that every poet I have painted has been a new experience and one of discovery. Like the landscape, I feel at home and comfortable with some places, others can be intimidating and dark. There is darkness and light in both the landscape and the people who inhabit it. When I am standing in the landscape at my easel, I often find myself in a state of trance. Working with a portrait is much the same. I interact with the land by walking over it, studying its moods, and lines; with the poet I drink tea and communicate with words while trying to understand and study their essence ... that's what I am searching for - in a sense, the photographic face of each person is less important to me as a painter than the feeling and presence I gain from them. This needs to be experienced firsthand and face to face - to try and gain that from a photograph is almost impossible, unless some time has been spent in conversation. Even then, it may take a while to understand and feel something about the person. Landscape can be elusive too. Sometimes, there is at first a strong connection and a bonding grows into a true friendship. Again the landscape is the same. Places are returned to, or visited only once.

Sometimes I have a preconceived vision of the poet and how I may paint them, only to find when I begin to spend a little time with them that I was quite wrong - the public image and the private are often quite the opposite. I read poems from each of the poets before I begin to paint. It's a starting point only in attempting to understand a way in which to paint them ... sometimes, the poetry and the person are different - we talk about ways of working, so often they are similar: the poet dreams and wanders his subject as I wander across the hills. There is a shared passion with the landscape poet and the landscape artist, a mutual understanding. Who else could see the beauty in dusty wheatfields with crows flying over? The poet, like the painter, sees a work of art in a burnt-out landscape, the possibility and music from a drought, a flood or the art in an abundance of wormwood growing from a stone ruin.

The poet and the painter can work well together with their separate and similar sensitivities to what is around them and I am surprised more collaborative work is not undertaken. Poems and paintings are merely the fruition of shared visions and each walking together into the landscape can inspire the other.

Working in the studio with the poet in the seat is also a sharing for I could not paint the poet if he or she didn't allow me to enter their world for that moment. Painting a portrait is more than getting a likeness of a person. For the artist looking at a photograph of a person there is a two-dimensional image that can be transposed onto the canvas; however, generally the painting will not be more than that - a two-dimensional image on canvas. I usually take a series of photographs of each poet to be used as working images if required; and in the course of the few minutes I stand before the camera, I have a handful of moods of the person. For the artist standing before his or her subject, there are many faces that can be captured, and I hope my paintings are a combination of all of the states that change before me. During the making of a painting, there is conversation and observation of a variety of thoughts and moods that the sitter changes into and from. Sometimes we share a joke or a tear, or share inner secrets, happy times and encounters. Generally, while often the subject is animated, I wait until they resume their still position. This is the point which I believe is each person's resting place - the place between our thinking and moving; the place we return to; it is what gives us our unique self. It is what others recognize us from, our body language. It is the place of unconsciousness, where we are when we are not aware of holding ourselves publicly, where we relax and become ourselves. The still position is where the dream is born, the poem and the painting.

On completion of the 100 Paintings of Australian Poets' project they will be kept together in a publication along with a poem from each of the poets and their biographical notes. This book will be a guide to a cross section of contemporary poets working in the latter part of the 20th century in Australia. Selections of the paintings have toured Tasmania and been on exhibition at the Victorian Writers' Center as well as being featured at the National Montsalvat Festival on several occasions. My vision is to find a permanent home for the 100 paintings and see them toured in groups or together, with readings from the poets work.

Some of the poets who have sat for me: A. D. Hope, Judith Wright, Les Murray, Shelton Lea, Tom Shapcott, Judith Rodriguez, Dorothy Porter, Jennifer Harrison, John Anderson, Emma Lew, Ken Taylor, Robert Kenny, Coral Hull, John Kinsella, Mark O'Connor, Alan Gould, Lauren Williams, Cornelis Vleeskens, Pete Spence, Geoffrey Dutton, Rebecca Edwards, Geoffrey Goodfellow, Geoffrey Eggleston, Kris Hemensley, Gary Catalano, Pam Brown, Chris Mansell, Ian McBride, Jordie Albiston, Joyce Lee, Barbara Giles, Shelton Lea, Rudi Kraussman, Nigel Roberts, Terry Gilmore, Robert Adamson, Peter Porter, Evan Jones, Alex Skovron, Mal Morgan, Eric Beach, John Tranter, Jennifer Maiden, Peter Goldsworthy, Peter McFarlane, Bob Brissenden, Tom Grant, John Rowland, Geoff Page, Maggie Grey, Clem Christensen, Bev Roberts, Michael Sharkey, Chris Wallace-Crabbe, Tim Thorne, Kristin Henry, Adrian Rawlins, Fay Zwicky, Alan Wearne, Gwen Harwood, Barbara Blackman, Ken Bolton, Anne Edgeworth, Rob Riel, Mark O'Flynn, Peter Rose, Gig Ryan, Lisa Bellear, David Brooks, Roger McDonald, Cassie Lewis, Jamie Grant, Dipti Saravanamuttu, Meredith Wattison, Nicolette Stasko, Rhyll McMaster, Ern Malley, Carl Leddy, Philip Salom, Ken Smeaton, Jennifer Strauss, Peter Boyle, Adam Aitken.

About the Writer Jenni Mitchell

|

Jenni Mitchell is best known as a painter of the Australian landscape and of Australian poets' portraits. She has travelled extensively throughout the inland regions of Australia, particularly the Flinders Ranges, Lake Eyre and Tibooburra. Jenni has visited the Wimmera and Mallee regions of Victoria frequently, and is interested in the Little Desert and Mt. Arapiles. Jenni's series of poets' portraits is another project involving historical documentation, commenced in 1981, since 1981, over ninety paintings have been completed to date. Portraits include such notable poets as Prof. A. D. Hope, Judith Wright, Les Murray, Dorothy Porter, Chris Wallace-Crabbe, and Geoffrey Dutton. The portraits are to remain together as a permanent collection. They have been loaned for various exhibitions including a six-month touring exhibition of Tasmania, and will continue to be exhibited in part or in total. Publication of a book is planned, once the series is complete. Jenni has had more than 30 solo exhibitions throughout Australia, and has been included in many group exhibitions. Her works are represented in public and private collections in Australia, and overseas, including USA, UK and Japan. |

[Above] Photo of Jenni Mitchell by Lawrence, 1998.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.1 (March, 2000) |