THE INTIMATE LANDSCAPE OF AUSTRALIAN POET JOHN ANDERSON

By Ned Johnson

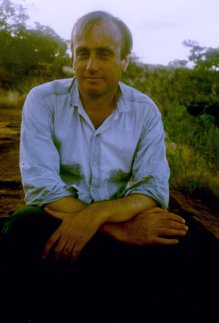

[Above] John Anderson in the Pilbara, Western Australia. (Photo by Emma Lew, 1997)

"Stop the car," he would call, then clamber out onto an unremarkable roadside to find the thing he was looking for - a wildflower, an insect, a fungus, or, down a slope in a hidden gully, a particularly fine specimen of gum tree. Sometimes it required an effort of imagination to see what he saw, sometimes the revelation was powerful and immediate.

Driving in the bush with John Anderson was a slow business and stops were frequent. He was a teacher. Often he would simply gaze and point. Such gestures were irresistible. He was a student of nature, a committed discoverer of gems in abused and neglected places. He was also one of the best Australian poets of his generation.

Anderson, physically, left a vivid impression. Tall and rangy, with long brown hair and dark hooded eyes, he moved with an awkward grace, approaching people with a hesitancy that masked the extrovert's love of company and attention. He had no interest in money or possessions - apart from books, small artworks and found objects that he collected. He loved to travel, and knew most of Australia. He walked, he slept on the ground in the open, he knew places intimately.

|

John Anderson was born in 1948 and grew up on an orchard in the Goulburn Valley near Kyabram, Victoria. His mother's love of literature inspired him to write; his father inspired his interest in nature. He knew he was a poet from an early age. His two preoccupations came together in his life's project: to create a poetry of the Australian landscape.

His early poems are exuberant and witty; they don't take themselves seriously. But through the seventies he became aware of the importance and seriousness of his theme. His writing acquired a foundation of careful research as he studied his subject, maintaining copious notes in the innumerable exercise books that accompanied him on his travels. He recognised that we were not made for the world that we have made; we are organic and belong more truly to the natural world. He set out to describe that world so that people could place themselves within it.

Anderson's poems are often didactic, seeking to indicate the neglected spaces that people have shunned, and urging reconciliation with the natural world. This is no yearning for a lost Arcadia nor New Age rejection of technology; it is a desire for the integration of our two worlds, for completeness. |

[Above] Photo of John Anderson by Gail Hannah, 1995.

He travelled widely in Europe, Asia and New Guinea but he found the subject of his poetry in his native land. In Australia, Europeans and their culture were still in transit. In two hundred years they had changed the landscape utterly; they had been in such a hurry to master this strange continent that many things were lost before they were recognised. Few European Australians have achieved an organic relationship with the land, and the uneasy feeling lingers of a people perched on the rim of a vast unknown, their over-confident philistinism evidence of deep disconnection.

Anderson's poetry argues persistently, quietly, for people to make connection with the natural world, to value the roadside things they drive past, to value and relate to their landscapes as they value and relate to one another.

Many Australians still experience the feeling of being in a backwater, of being carp in the antipodean stream. Internationalism has been embraced by many, and has provided some solace, but no sense of identity. Anderson's poetry seeks to create an integrated identity, applying the English language to the Australian landscape. Integration of European and native is still unusual in Australian public life, where a Prime Minister can refuse to apologise for two centures of abuse for fear of lawsuits.

|

Anderson's is by no means a solitary voice. More and more people are finding spiritual values in the countryside, more and more are seeking a deeper knowledge of the land that was an adversary to earlier generations. Sustainable agriculture is widely understood and practised now, and landcare is a primary concern of many farmers. Millions of ordinary Australians desiring reconciliation have made their own private apologies to the Aboriginal people. Now is the time for Anderson's poems to speak to this wider audience.

Unlike Les Murray, who writes of a people and their culture, and for whom the landscape is an element in a human narrative, Anderson celebrates his land for its own sake; he writes landscapes. His is a poetry of particular places. He rediscovers the sacred in natural things, where the sacred always ultimately resides.

His method is to reveal the landscape as something other than the despised and abused hillsides and weed-choked watercourses that we disregard in our daily lives. He names things and their relationships - the gum trees in moonlight, in a mystical alliance with the stars; glints and sparkles in the leaf litter at midday; birdcalls. He uses dreams and dream images to evoke the sacred in these everyday things. |

[Above] John Anderson in a billabong, Central Victoria. (Photo by Emma Lew, 1996)

He develops a cosmography of natural forms: the lanceolate gum leaf mirrored by the lanceolate parrot; the round pebble tortoise mirrored by the river stones. He sees how natural forms complement and repeat one another, and argues that surely we too can be part of this complementation, this shaping and accommodation.

His short lyrics are full of bush music - the whispering grasses and grass birds, the violet magpie songs; while deeper rhythms are developed in the longer poems, the rise and fall of the mountain ranges, the tides, the seasons.

Anderson's poems have a natural clarity, but often he pushes words beyond everyday syntax to describe the experiences whose expression lies at the limits of language - the gestures, the strange juxtapositions that arise in dreams. He retains the words of dreams and explores their multiple suggestions. He exposes deeper levels of human consciousness and understanding, and lays bare those underlying connections, the filaments of desire that touch the rocks, reach in to the hollows and bind us to the stars. Our love, our capacity to love, depends on our love for the natural world. That is our hope for completeness. Anderson knew, and said over and over, that we could be here, in this world, fully, completely, if only we could give our attention to the natural world around us. An attunement. A walk along the creek.

His beautiful lines are more beautiful because they are unexpected: he doesn't strive for them; they arise naturally in their places - the holy trees, the cascades of stars and the river redgums by the river. In his last poems, among them the haunting pantoums, he writes with poignancy, and an awareness of his mortality.

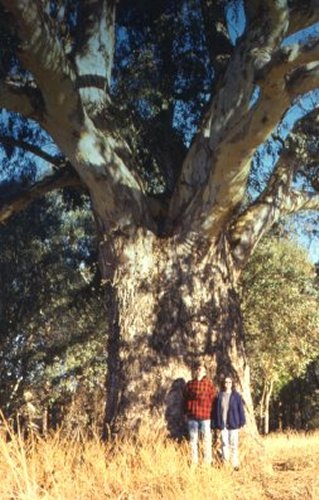

[Above] John Anderson, Emma Lew and Dora outside Perth, Western Australia. (Photo by Roly Anderson, 1997)

John Anderson was well-known in Melbourne poetry circles for twenty years or more. In the mid-seventies he was introduced to the New Poetry scene by Kris Hemensley, and Robert Kenny, who published his first book, the bluegum smokes a long cigar in 1978 in the Rigmarole series. He was a frequent reader at poetry festivals, published in many Australian poetry magazines, and read on radio, but seventeen years passed before his second book appeared: the forest set out like the night (Black Pepper, 1995). He wrote slowly and worked on poems for long periods before he was satisfied with them. Even then, publishers were luke warm. His preoccupation with landscape did not attract them much in the eighties, and his writing was not considered mainstream.

The tide turned in the nineties, and in recent years his work has received tributes from all quarters. He was awarded a major Australia Council grant in 1996 to pursue a study of gorge landscapes. His third book, The Shadow's Keep (Black Pepper, 1997) was published just prior to his death and received considerable acclaim. Anderson died suddenly of leukaemia in October 1997, shortly after returning to Melbourne from a three-month tour of the Hamersley Ranges in Western Australia. A Selected Poems is in preparation.

JOHN ANDERSON WRITES ABOUT HIS WORK FROM 'THE SHADOW'S KEEP'

The Beginning Tincture of What I Wrote

The lines gathered here represent a variety of dream phenomena. Most can probably be explained at a mundane level by my sleep apnoea, which prevents the normal onset of deep sleep. This brings about prolonged spells of relative alertness to events taking place at the bay of sleep.

The experience of receiving these lines is often close to that of everyday thought. They are like thoughts. I am composing my thoughts and then something seems to be doing it for me. Unmaking the thought and making something else.

It is as if the rather desultory images swimming before my eyes, marbled grey and brown, suddenly undergo a sea change and become the most exquisite and alert little fish, glowing in the palest shades of pink and blue and green.

|

I have become practised in the capture of the bubbles of words, the sputterings that slip by me. Even so, they usually escape, and I surrender to sleep.

Other lines are much more powerful. The sense of the words being conveyed, and the importunate edge to their delivery, are so startling as to always awaken me.

Just as the lines can seize me at the cusp between sleeping and waking, so they can seize me in the midst of a dream which is not related to them in any way. It is as if I am registering a language with its own strange undertone, that has rolled through from somewhere further back, from some other plane of dreaming.

It is not a visual language. It is one of word and tone.

On those rare occasions when there has been a visual component, a line is set within a dream. Such lines seem diminished when presented without their dream context.

For example, the words the peacock's physician were accompanied by the image of a butterfly beating through rainforest, each wingbeat disclosing now deep red, now rich blue iridescence. (See my appropriation of the words and image within the text of the forest set out like the night, p101.) The image seals an understanding of the words. |

[Above] John Anderson and Emma Lew, Murray River, Central Victoria, Australia (Photo by Coral Hull, 1996)

For me, the dreamlines share many of the qualities of poetry, and some stand as individual poems. They have an aptness of language (even where a word is the concoction of the lines themselves), a decided tone, distinct rhythm and vibration, surprise and resolution. They have the power to awaken, as poetry can.

The first lines I recorded were, by a shade, the most peculiar, the most cryptic. Although I always felt privileged to be receiving them, they at first disturbed as well as fascinated me.

At the beginning I was more inclined to seek to understand and, if possible, be true to whatever they were trying to tell me. However, contrary interpretations could often feasibly be drawn from the same line.

If I relaxed and simply let the lines happen, they seemed eventually to explain themselves in ways that were more surprising than any I could arrive at consciously, and in a more subtle and richly suggestive language which, as I gave into it, gradually became less Rhadamanthine in its overtones, softer and more playful.

For instance, I had puzzled over the line: don't alter, but preserve it in its sweet sleep, its inventive mind...

If this were a comment about the reception of the lines, did it imply that the lines weren't mine to touch, that they were endogenous and that I was simply some kind of receiving station, with attendant responsibilities nonetheless as to how they were to be communicated to a wider audience? Or, obversely, was it an interdiction, a demand that I agree to keep silent?

To an extent, however, I found myself incorporating the lines into my work.

Vital words or phrases that would complete or progress a poem might sometimes (if rarely) be contained in a dreamline. It seemed that such lines would only be generated when my writing had reached a particular pitch.

[Above] John Anderson in Coral Hull's EH Holden, Stuart Highway, South Australia, Australia. (Photo by Emma Lew, 1996)

I might have to manipulate the wording of the line in question to fit my purpose, but I could feel that the dreamlines approved, that they had presented themselves to be just so used, that my writing had been elevated by their inclusion.

Simply writing the lines down on the page in a sense altered them, severed them from their medium of dream, from whatever words had preceded or would have followed if I had not woken and exposed them to a critical waking consciousness. Even if grouped in the pristine chronology of their occurrence, they might be rendered mere specimens drained of their richness and colour, like stones that need to be put back in the water before they gleam.

How were the lines to be arranged for publication?

The understanding of any line would be influenced by the lines placed around it.

And yet the lines are complete in themselves, and are often more roundly suggestive when taken singly. Days or weeks may have intervened between their occurrence in real time, but the reader would be experiencing them crowded one upon the other.

Lines that had affected me powerfully, their possible significances slowly stealing upon me, could easily be lamed by an inappropriate juxtaposition.

If I could, I would arrange the lines so as to let them expand infinitely into their own universes, infinitely in all directions. But I was faced with the knowledge that any arrangement could, by subjecting it to a subordinate status in a consciously wrought greater structure, corrupt the understanding of a given line as a discrete utterance. This said, clearly there are lines of a kind which seem to ask to be placed together.

|

Lines that might have arrived years apart. And there are lines that seem to have no obvious place beside any other lines at present, but which may find their own company in time.

A chronological presentation of the lines would be very different. Lines of a common tone or concern would show some tendency to correspond with distinct periods in my life.

Played against biographical details, a fuller and more accurate divination of their meanings might have been possible.

But to present them in even an approximate chronological sequence would be difficult now.

I never dated the lines. They were written down hastily on scraps of paper, scattered through notebooks, collated months or years later.

And while in a sense the lines ghost my personal history, it is equally true that each one emanates from its own time, its own dream-continuum.

Typically, a brooding line is followed in rapid succession by one of a joyous, optimistic nature, a line about the process of writing, a line about the lines themselves.

A chronological presentation could appear as a jagged graph of seemingly unrelated material. The pantoum form offered me a way to present the lines in a kinetic relationship with each other. |

[Above] John Anderson at Stanley Chasm, Central Australia (Photo by photographer unknown, 1996)

The pantoum takes as its starting point, the understanding that any single line will be influenced by the lines placed around it.

It allows the lines to find themselves in shifting contexts and, in so doing, capitalises on their inherent ambiguities.

Writing the pantoums brought about a different kind of engagement with the lines. It involved sifting and re-sifting them to find which lines interacted most suggestively.

I had not wanted to present them as a catalogue. Often, on waking, I wished that I had been able to let the dream voice run on a little further, to see how one utterance led on to another.

The pantoum provided a means to suggest extended dialogues by sleight of hand.

It allowed the lines to talk among themselves in their own language, to reveal facets of themselves much more clearly than I could by writing about them.

[Above Left] She-Oaks in Central Victoria where John said 'Stop The Car!' (Photo by Coral Hull, 1996) [Above Right] John Anderson handing Emma Lew a small plant. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1996)

Some individual lines seem like keys, ciphers - unlocking, unravelling other lines, and in the pantoum I could activate and explore this effect. It was a form that enabled me to do with the lines something that dreams do - explore the paths not taken. By venturing line against line, I was able to build a narrative path, or landscape, or argument with its own hermetic logic.

A line might have been used in a different combination or in another pantoum and have led to another place.

Writing the pantoums engendered a spate of lines about writing, lines like the beginning tincture of what I wrote, which in turn provided the theme for a new pantoum.

When I received the line, "You, the new poem, stalking on your why's ways", while composing this piece, I was tempted to take it as confirmation that I had, so far as is possible, become the agency of whatever it was that the lines wished expressed. Perhaps, by writing the pantoums, I was participating in, creating an epi space, where the legend itself, Art, can be freely thrown about.

I am sure that writing the pantoums gave me confidence for the task of arranging the lines in the first section of this book, given the considerations mentioned earlier in this essay.

The experience alerted me to the possibility of assembling them as a complete poem, grouping lines of a kind in drifts, or as loosely linked poems within a longer poem.

And it gave me practice in the art of composition, the tuning of line to line.

Some of them are particularly chameleon-like, more charged with possible meanings, for example It is an impossible question. Don Juan let go of it only to interfere all the time. They have the potential to powerfully affect the reception of the lines placed around them.

The art was in finding the optimum combination and, wherever possible, to not violate what I understood as each line's core meaning.

In the end, I hope, a verisimilitude was attained. But the introduction of a certain, almost subliminally present narrative flowing through the whole tended to override all the little narratives that were attached to each individual line. Those lines, for example, which were situated within dreams, spoken by a variety of dream characters, and which were now appropriated by the one voice.

So what I have created is in part a fiction. The lines could have been arranged differently to other effect. But while some of the qualities of these lines may have been diminished by the mode of presentation, I feel that their dreamlike and often delicately poetic nature has been enhanced.

How do the lines relate to my life?

The lines have their own life. Many are clearly generated in part by the concerns of my writing with the natural world and more with the process of language and writing itself. And yet I don't feel I can claim an identity with them. I have a certain privileged understanding of quite a few, but as many leave me guessing. A casual reader's interpretation of a line can often be more open and less conditioned than my own. I am also an outsider, a reader who can draw parallels between the lines and his life but who is not their authority.

|

The lines are their own best authority. They have their own understanding of me, of themselves and the world. For example, they understand life in terms of reincarnation. I can imagine life in their terms but not with their certitude, although I may have claimed such certitude for the purposes of a poem, wishing to explore the state of being that such a belief allowed. See these lines:

I believe everything has been told

I like to hear the ripples of the telling

the croon of the gums

the violet magpie songs

(See p.70 the forest set out like the night. The first two of these non-dreamlines were also imported into the pantoum, Deep Sea Faith - see p. this text.)

This said, there is a heightened state of receptivity to ideas and the poetically right phrase when deeply involved in the act of writing that is like the dream state. It involves a relaxation of conscious control. It is a waking state you must work to achieve.

You wish the writing to flow like a dream. Your aim is to throw everyday logic all to the winds, to write as if you knew, to have the words just drop into place, to allow something to come through. |

[Above] John Anderson and Emma Lew beneath River Red Gum, Winninninnie Creek, South Australia, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1996)

You are prepared to claim the preposterous, to assume the grandest airs, to try any strategy, if it will let you see a little further, draw into prominence something of what is more often undervalued.

And this is similar to what the dreamlines do. They jockey, they chide, they tease, they exalt - anything to gain your attention. They scout the neglected territories. They illumine the mundane ...

the choice of a subject like the choice of a glance

An underlying equivalence of concerns between my dreaming and waking states can perhaps be shown by the following dream:

I was at the court of Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain. I was pouring two identical piles of coffee crystals on the table before them, and saying of one pile, "This is the Earth" and of the other, "These are the Crown Jewels".

I remember a vignette from a children's version of the story of Christopher Columbus. Columbus, representing the earth and its roundness with an egg, demonstrates to the King and Queen by the tracing of his finger the feasibility of reaching India by sailing west.

To me this dream is about the folly of singling out any one part of the earth as more precious than the whole.

As a poet I have attempted to declare something of this truth. One of the things the dreamlines do is chart a writer's progress in the task that he has set himself.

The line the shadow's keep, (received as in the shadow's keep), for me bears particular geographic connotations as well as describing the realm from which the dreamlines emanate.

I was hitchhiking back from Central Australia through the Flinders Ranges.

[Above Left] John Anderson and Emma Lew, Stuart Highway, South Australia, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1996) [Above Right] Island Lagoon, Stuart Highway, South Australia, Australia. (Photo by Coral Hull, 1996)

I was musing on the diaspora of the redgums, their presence - huge, isolated and absolute in the desert spaces, rising as a wall along the dry riverbeds.

Their slow retreat into the deep gorges of the Macdonnell Ranges.

The mountains themselves, pared down, elemental.

Although this land had been substantially degraded by years of overgrazing, there was a feeling that here a vast integrity reigned.

The redgums had never been culled. There were few roads or buildings.

In many places there seemed to be just sand, low bushes, space.

My daydream was interrupted by the reception of the line, in the shadow's keep.

The sandhills, the plains between the ranges, the ranges themselves - all were abandoned to the absolute, in the possession of the shadows.

However, it was in relation to the mountain gorges that the line assumed its greatest significance.

The observer walking above them was bathed in the most intense light. But below, the gorges caught majestic pools of the deepest shadow. He would have to shield his eyes and squint to make out the forms of the pines, the cycads, the rock features that lay within. The redgums, so visible on the plains, had become the underneath - in the shadow's keep.

Acknowledgement for poems published on this website is given to Black Pepper, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

About the Poet John Anderson

|

John Anderson was born in 1948 and grew up on an orchard in Kyabram, Victoria. In a writing career spanning 25 years, he published three volumes of poetry: the bluegum smokes a long cigar (Rigmarole, 1978), the forest set out like the night (Black Pepper, 1995) and The Shadow's Keep (Black Pepper, 1997). The main subject of his poetry was the Australian landscape, and he examined it closely: the stones, the soil, the water and the living things, both large and small. He reclaimed the neglected places of this continent as well as the well-known ones, and from them he forged a new account of it and he made common cause with all poets who celebrate nature. Anderson's real inspiration came from his native land. From his Melbourne base he explored the continent, seeking out the secrets of desert landscapes, of roadsides and forests and waterways. He knew the seasons of the gums, the grasses and the insects. He described the interconnectedness of things, of stars drawing towards the earth and reaching down to the trees and stones, the leaf-forms and the landforms. John Anderson died, after a short illness, in 1997. His acclaimed second book, the forest set out like the night had earlier brought his understandings and sensibilities to the forefront of contemporary Australian poetry. |

[Above] Photo of John Anderson by Emma Lew, 1997.

I Next I

Back I

Exit I

Thylazine No.1 (March, 2000) |